#puerto rican literature

Text

Julia de Burgos, tr. by Jack Agüeros, from Song of the Simple Truth: The Complete Poems of Julia de Burgos; "Moments"

[Text ID: “Me, inside myself, / always waiting for something / that my mind can’t define.”]

#julia de burgos#excerpts#writings#literature#poetry#fragments#selections#words#quotes#poetry collection#typography#poetry in translation#puerto rican poetry#puerto rican literature

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

physical copies of my poetry chapbook came in! get yours now here!!!!

#poetry#poet#poetry chapbook#queer writers#writing life#am writing#bottlecap press#puerto rican writer#boricua writer#puerto rican literature#puerto rico literature

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

— julia de burgos, song of the simple truth: the complete poems (1995)

[text ID: Meanwhile, your life and my life have kissed.]

#*#julia de burgos#poetry#literature#dark acamedia#light academia#romantic academia#quotes#love#soulmates#lit#words#classic literature#puerto rican literature

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Naturalmente Mío (Afro-Latino)

Tienes que amar mi cabello. Es un mundo de rizos.

Todas las diferentes formas, tamaños y texturas con

solo una pizca de sal y pimienta. mi cuero cabelludo es

Con sabor a Nueva York: sigue mi viaje: Mis hebras

podría formar un círculo alrededor - Ludlow Street para Christopher Street un sábado por la noche pero

Estas raíces serán todas de Harlem. Mis consejos se doblan hasta el centro de Brooklyn, a través de la 2 o

el tren 3 durante los húmedos meses de verano

mi patrón de rizos se vuelve más apretado que un

acera en Times Square, el otoño

Los vientos de octubre tienden a dejarme el pelo.

Más salvaje que una pelea con cuchillos.

como el concreto

Los ladrillos del invierno forman mi cabello

un acabado de laca impecable

pero solo después de co-lavar y luego enjuagar

Y luego relajo mi cabeza contra mi almohada de satén.

caso... durante esas frías noches de invierno dejando

extremos duros y quebradizos que arrojar su camino hacia un nuevo amanecer…

#poetry month#afro latina#hispanics#latinx#black theme#black tumblr#black history#black literature#puerto rican#hispanic#black entrepreneurship#critical race theory#black fashion#weekend#brazilian

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

If it’s a phase, so what? If it’s your whole life, who cares? You’re destined to evolve and understand yourself in ways you never imagined before. And you’ve got our blood running through your beautiful veins, so no matter what, you’ve been blessed with the spirit of women who know how to love.

– Gabby Rivera, Juliet Takes a Breath

#book quote of the day#gabby rivera#juliet takes a breath#ya#feminism#lgbtqia literature#Hispanic Heritage Month#Hispanic Heritage Month reads#lesbian#book recommendations#puerto rican protagonist#bookblr

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The historical struggle against colonialism and imperialism ... is waged at the same time as a struggle over the historical and cultural record. One of the first targets, for example, of the Israeli Defense Forces when they entered the Lebanese capital of Beirut in the fall of 1982 was the PLO Research Center and its archives containing the documentary and cultural history of the Palestinian people.

Similarly the United States police squadron which in August 1985 arrested in San Juan, Puerto Rico, eleven Puerto Rican independentistas on charges of bank robbery and violation of interstate commerce laws also entered the offices of the journal Pensamiento critico where they confiscated the journal's archival resources as well as its copier and typewriter. The struggle over the historical record is seen from all sides as no less crucial than the armed struggle."

Barbara Harlow, Resistance Literature (1987)

403 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today We Honor Arturo Alfonso Schomburg

One of the most influential forces behind the creation of The New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture is the man the research center is named after, Arturo Alfonso Schomburg.

Born in Puerto Rico in 1874, Schomburg was a Puerto Rican of African and German descent. Young Arturo often wondered about the lack of African history taught in his classrooms. This interest formed the cornerstone of Schomburg’s eventual lifework consisting of research and preservation—work that would lead him to become one of the world’s premier collectors of Black literature, slave narratives, artwork, and diasporic materials.

During the 1920s and '30s, Schomburg traveled to Europe, Latin America, and across the United States collecting new materials that bolstered his already voluminous collection, and in 1926 the Carnegie Corporation funded The New York Public Library’s purchase of Schomburg’s private collection for $10,000.

This would mark the beginning of the 135th Street branch’s transformation into the Schomburg Center.

Schomburg’s curation work was so heralded that in 1929, Fisk University President Charles S. Johnson invited him to curate Fisk’s library. By assisting in the architectural design of the library and focusing on providing equitable experiences for researchers, including the building of a reading room and browsing space, Schomburg helped cement Fisk’s standing as one of the leading institutions on Black research and studies. By the time Schomburg ended his tenure at Fisk, the library’s collection had expanded to 4,600 books from a mere 106 items.

CARTER™️ Magazine carter-mag.com #wherehistoryandhiphopmeet #historyandhiphop365 #cartermagazine #carter #arturoschomburg #blackhistorymonth #blackhistory #history #staywoke

#carter magazine#carter#historyandhiphop365#wherehistoryandhiphopmeet#history#cartermagazine#today in history#staywoke#blackhistory#blackhistorymonth#Arturo Schomburg

124 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“We need the historian and philosopher to give us with trenchant pen, the story of our forefathers, and let our soul and body, with phosphorescent light, brighten the chasm that separates us. We should cling to them just as blood is thicker than water. American Negro must remake his past in order to make his future.”

...

Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, collector, archivist, writer, activist, and important figure of the Harlem Renaissance was born in San Juan, Puerto Rico on January 24, 1874. His mother was a black woman originally from St. Croix, Danish Virgin Islands (now the U.S. Virgin Islands), and his father was a Puerto Rican of German ancestry.

Seventeen-year-old Schomburg migrated to New York City in 1891. Very active in the liberation movements of Puerto Rico and Cuba, he founded, in 1892, Las dos Antillas, a cultural and political group that worked for the islands’ independence from Spain. After the collapse of the Cuban revolutionary struggle, and the cession of Puerto Rico to the United States, Schomburg, disillusioned, turned his attention to the history and culture of Africa and what we know today as the African Diaspora.

In 1911, as its Master, he renamed El Sol de Cuba #38, a lodge of Cuban and Puerto Rican immigrants, as Prince Hall Lodge in honor of the first African American freemason. The same year, he founded, with journalist John Edward Bruce, the Negro Society for Historical Research which gathered African, Caribbean, and African American scholars. In 1922 he was elected president of the American Negro Academy.

Schomburg firmly believed that “The American Negro must remake his past in order to make his future.” The first part of this process was to reclaim history by evidencing Black people’s contributions to history and culture. Working as a mailroom supervisor at a Brooklyn bank, Schomburg spent his free time and resources, and his retirement after 1930, collecting materials on Africa and its Diaspora. He traveled through the United States, Europe, and Latin America, amassing over 10,000 books, manuscripts, sheet music, photographs, newspapers, periodicals, pamphlets, and artwork.

The second phase of Schomburg’s project was to bring this knowledge to the public. He lent numerous items to schools, libraries, and conferences and organized exhibitions. He wrote articles for a diversity of publications: Marcus Garvey’s Negro World; the NAACP’s The Crisis edited by W. E. B. Du Bois; The Messenger, founded by Socialists A. Philip Randolph and Chandler Owen; the organ of the National Urban League, Opportunity; and Harlem’s newspaper, The Amsterdam News.

In 1926 the Carnegie Corporation bought Schomburg’s collection for $10,000 (about $125,000 today) on behalf of The New York Public Library. The collection was added to the Division of Negro Literature, History and Prints of the Harlem branch on 135th Street.

From 1929 to 1932 Schomburg worked as a curator at Fisk University’s library and was instrumental in expanding its collection from 100 to 4,600 items. Back in New York, he was appointed curator of The New York Public Library’s Harlem Division. He held the position until his death on June 10, 1938 in Brooklyn. He was 64. In his honor, the Division was renamed the Schomburg Collection of Negro Literature, History and Prints in 1940. Arturo Schomburg’s enduring legacy was further acknowledged when the Collection became the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of The New York Public Library in 1972. With over 11 million items, it is one of the world’s foremost research centers on Africa and the African Diaspora.

Legendary.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Julia de Burgos

Julia de Burgos was born in 1914 in Carolina, Puerto Rico. In 1938, at the age of 24, de Burgos published her first poetry collection, Poem in Twenty Furrows. She was a supporter of Puerto Rican independence and a member of Puerto Rico's Nationalist Party. Her poetry dealt with colonial violence in her homeland. In 1939, de Burgos published another poetry collection, Song of the Simple Truth, for which she won the Puerto Rican Institute of Literature Award. In 1940, de Burgos left Puerto Rico. She ultimately settled in New York, where she worked as an art and culture editor for Pueblos Hispanos, a progressive newspaper.

Julia de Burgos died in 1953 at the age of 39. Another collection of her poems, The Sea and You, was published posthumously. Today, many cultural centers, parks, and schools are named for her.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The American Negro must remake his past in order to make his future."

This summer, let us browse the stacks of the remarkable life and career of archivist, collector, and curator Arturo Alfonso Schomburg (the "Father Of Black History"), without whom there almost certainly would not have been a Harlem Renaissance. Born in 1874 Puerto Rico to a black mother (from the Virgin Islands) and a Puerto Rican father of German ancestry (hence his distinctive surname), Schomburg recounted a childhood tale of a bigoted grade school teacher in San Juan, who asserted that black people had "no history, art or culture." He moved to New York City in his teens but he never forgot this racist sentiment, and he remained fiercely connected to his Puerto Rican heritage. Activism called to Arturo early; in 1892 he was deeply involved with Las Dos Antillas, an advocacy group that pushed for Puerto Rican independence from Spain --a mission which of course sputtered to a disillusioning end after Spain ceded Puerto Rico to the United States.

Schomburg pivoted to academic life and embarked on a study of the African Diaspora. In 1911 he co-founded the Negro Society for Historical Research, a long-term reclamation project in which materials on Africa and its Diaspora were collected. Schomburg would devote the next 20 years of his life to this project --travelling throughout the United States, Europe, and Latin America to rare book stores, antique dealers, and even used furniture stores (one from which he apocryphally claimed to have recovered a handwritten essay by Frederick Douglass). Over time he and his team of African, Caribbean, and African American scholars would amass a collection of over 10,000 books, manuscripts, artwork, photographs, newspapers, periodicals, pamphlets, and even sheet music. One of his proudest finds was a long-forgotten series of poems by Phillis Wheatley.

Of course as any curator will tell you, acquiring unique pieces is nothing without a means to share the knowledge and the history that comes with them --by 1930 (the year of his eventual retirement), Schomberg would have lent numerous items to schools, libraries, and conferences and organized exhibitions. In the midst of all this he wrote articles for a wide range of publications, to include Marcus Garvey's Negro World; the NAACP's The Crisis (edited by W. E. B. Du Bois), and A. Philip Randolph and Chandler Owen's The Messenger; as well as essays for the National Urban League and The Amsterdam News (Harlem's newspaper).

Significantly in 1926 the Carnegie Corporation bought Schomburg's collection for $10,000 (about $125,000 in today's currency), on behalf of The New York Public Library. The collection was added to the Division of Negro Literature, History and Prints of the Harlem Branch on 135th Street, of which Schomburg would later be appointed curator (following a stint as curator of the Negro Collection at Fisk University). The Division became the "go-to" centerpiece of many a Black artist, writer, and scholar; to include Arna Wendell Bontemps and Zora Neale Huston. After his death in 1938, the Division was renamed the Schomburg Collection of Negro Literature, History and Prints. Schomberg's protégé, an up-and-coming author and poet named Langston Hughes, assumed responsibility for the collection.

Today the collection is known as the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture (still under the auspices of The New York Public Library) --now topping out at more than 11 million indexed items, and considered to be one of the world's foremost research centers on Africa and the African Diaspora.

#blacklivesmatter#dothework#teachtruth#history detective#new york public library#arturo alfonso schomburg#harlem renaissance

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Julia de Burgos, tr. by Jack Agüeros, from Song of the Simple Truth: The Complete Poems of Julia de Burgos; "To Julia de Burgos"

[Text ID: "in all my poems I undress my heart."]

#julia de burgos#excerpts#writings#literature#poetry#fragments#selections#words#quotes#poetry collection#typography#poetry in translation#puerto rican literature#puerto rican poetry

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Atrocities US committed against WOMEN

In 2022, the US supreme court overturned Roe V Wade, ending a constitutional guarantee to the right to have an abortion, in place for over 50 years. In response, 26 US states are expected to ban abortion in their state. Women who become pregnant in red states, will now have to drive an increased average of over 200 miles to an abortion clinic. Protests erupted in hundreds of US cities, decrying the decision.

US police officers routinely commit sexual assault and rapes: most go unreported, but over 1200 incidents, including over 400 rapes were committed over a 9 year period from 2005-2013.

In the period following WWII, the US capitalist-controlled media, advertising, and consumer products industries propagandized and glorified the ideal of the housewife-consumer, in order to sell products, make labor space for returning soldiers, take advantage of women’s unpaid labor in the home, and to help build a new workforce and potential army to combat the soviet union. This sparked an era of regression with respect to the feminist victories of the previous 50 years, and caused psychological damage and demoralization to an uncountable number of women. Women who remained in the labor force were primarily only allowed in subordinate positions such as secretaries, cleaning women, elementary school teachers, saleswomen, waitresses, and nurses. This is chronicled in the Feminine Mystique.

In September 2020, it was revealed that ICE had performed mass hysterectomies on immigrant women in several detention centers, reminiscent of the long-standing US policy of sterilization of black and brown women.

From the 1880s onward, many US states (27 + Puerto Rico in 1956) operated a system of forced sterilization of women, rooted in white supremacy. The principle targets were the mentally ill, Native Americans, and blacks. For example, in Sunflower County Mississippi, 60% of black women living there were sterilized without their permission. An estimated 3,406 Indian women were sterilized. California eugenicists in 1933 began sending their literature overseas to german scientists and medical workers, sparking the beginnings of Nazi Eugenics. In the end, over 65,000 individuals were sterilized in 33 states, in all likelihood without the perspectives of ethnic minorities. The US enacted a system of forced sterilization in Puerto Rico since its takeover by the US in 1989: a 1965 survey of of Puerto Rican residents found that about one-third of all Puerto Rican mothers, ages 20-49, were sterilized. 148 female prisoners in two California institutions were sterilized between 2006 and 2010 in a supposedly voluntary program, but it was determined that the prisoners did not give consent to the procedures. In Madrigal vs. Quilligan, many unsuspecting women were coerced to sign paperwork to perform sterilization, while others were told that the process could be reversed. None of the women were fluent in English. 10 latina women were sterilized, and the doctor was found innocent.

US elites in the 18th and 19th centuries pushed a narrative of domestic purity, or the cult of true womanhood, for women as a way of pacifying her with a doctrine of “separate but equal”-giving her work equally as important as the man’s, but separate and different. Inside that “equality” there was the fact that the woman did not choose her mate, and once her marriage took place, her life was determined. One girl wrote in 1791: “The die is about to be cast which will probably determine the future happiness or misery of my life…. I have always anticipated the event with a degree of solemnity almost equal to that which will terminate my present existence.” Marriage enchained, and children doubled the chains. One woman, writing in 1813: “The idea of soon giving birth to my third child and the consequent duties I shall he called to discharge distresses me so I feel as if I should sink.”

In 2019, it was discovered that US Border patrol had been protecting rapes and abuse of its own members since the 1990s. In one instance, a trainee was forced to give oral sex to 5 officers, and then raped while she was unconcious. At least 35 instances of rape by officers was found.

In May, 2019, Alabama lawmakers banned abortion in the state, providing no exceptions for victims of rape or incest. Those caught performing abortions will face up to 99 years in prison. The bill is part of a larger effort to overturn Roe vs Wade, a long-standing supreme court decision affirming a woman’s right to choose. Alabaman women seeking abortions are now forced to travel across state lines, and hide everything about the procedure from friends and family, in order to avoid legal repercussions from their home state. The American Civil Liberties Union has filed a federal suit against the state.

On November 25, 2017, Yang Song died after falling from a 4th floor balcony during a targeted police raid. Her personal messages revealed that in 2016, she was raped at gunpoint by an undercover police officer, and was subsequently harrassed, threatened with deportation, and then likely murdered by the NYPD.

In the 1830s, The Lowell Mill Girls were female workers who came to work in industrial factories in Lowell, Massachusetts, during the Industrial Revolution, and who despite living in cramped boarding houses and working from 5am-7pm every day, developed a culture of defiance against the factory owners, and created reform associations, and began strikes in 1834 and 1836.

#radical feminist safe#anti capitalism#socialism#anarchy#leftism#communism#radical feminists do touch#radical feminists do interact#social commentary#radical feminist community#radical feminism#american history#rip twitter#ronald reagan#imperialism#us history#us politics#radical feminists please touch#radical feminists please interact#serious

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

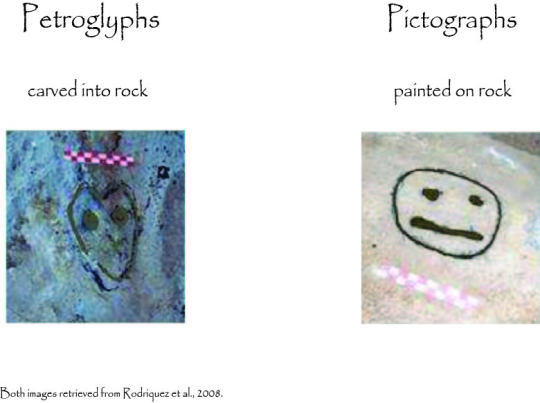

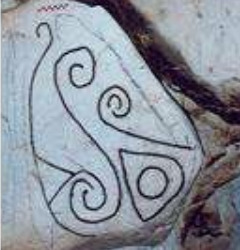

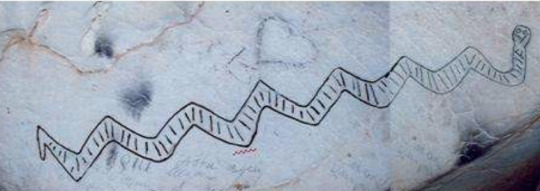

Puerto Rican Rock Art, Part 2

Hello and welcome to part 2 of my Puerto Rican Rock Art project! I will mostly be talking about Cueva Lucero (pictured above). I may mention other caves as well, just because there aren't many papers written about this specific cave. There are many others since about 81% of rock art found on the island is found in caves (Dubelaar 1994). I imagine it's just easier to talk about all the caves as a whole since they were all used similarly.

Cueva Lucero can be found in Juana Diaz in Puerto Rico. (Not from references).

However, due to fears of vandalism, the cave's exact location isn't listed in the National Register of Historic Places. In this same form, Cueva Lucero is deemed as important due to all the art found in it, this art shows us a part of the past we could have never seen without it. It is thought to be a place of religion or as a ceremonial site (Rodriguez et al, 2008). This cave was used around 600-1500 C.E., and represents mostly pre-Hispanic times and contains around 100 rock art images. That makes itself one of the best examples of pictographs in Puerto Rico (Rodriguez et al, 2008). While it has plenty of pictographs, it has petroglyphs as well.

The difference between petroglyphs and pictographs are that one is painted, and one is carved imagery. I included an example above.

There are three different types of landscapes that both these styles show up in:

A. Caves and rock shelters on the coast, created by the waves.

B. Caves and rock shelters found in the mountains.

C. Riverbanks and riverbeds.

As well, Puerto Rico has an extra type:

D. The petroglyphs found in Puerto Nuevo. They are engraved in flat sandstone ledge that run parallel to the coast (Dublelaar 1994). Pictured below.

Rock paintings found in Puerto Rico can be monochrome, bichrome and polychrome (Dubelaar 1994). They also can be found in a couple colors as well. Red, white, orange and black were most commonly used (Hayward et. al., 2009).

Cueva Lucero falls under type B, has most, if not, only monochrome paintings. Most are painted using the color black.

Here, you also see a lot of circles being used in their art. Obviously, using circles so much does suggest that the shape has importance for the community (Fewkes 1903). It can be seen as a sign of unity, which, is found in many other indigenous communities. Here are some examples of circle art found in Cueva Lucero.

Lots of circles.

That is about it for this cave. Cueva Lucero holds valuable knowledge about the past. Without it, the other caves, we wouldn't have been able to obtain as much knowledge from our Taino ancestors as we do now. This goes to show, these old paintings and carvings, sites we find on the island (sites where people lived, hunting sites), are vital to understanding our history.

All photos (unless otherwise stated) are pictures from Cueva Lucero. All but the very first photo are from Rodriguez et al. 2008.

My references:

Dubelaar, C. N. 1994. Prehistoric rock art in Puerto Rico. Latin American Indian Literatures Journal, 10(1): 78–82.

Fewkes, J. Walter. “Prehistoric Porto Rican Pictographs.” American Anthropologist 5, no. 3 (1903): 441–67. http://www.jstor.org/stable/659123.

Hayward, M. H., Roe, P. G., Cinquino, M. A., Alvarado Zayas, P. A. and Wild, K. S. 2009. “Rock art of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands”. In Rock Art of the Caribbean, Edited by: Hayward, M. H., Atkinson, L. G. and Cinquino, M. A. 115–136. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Lace, Michael J. “Anthropogenic Use, Modification, and Preservation of Coastal Cave Resources in Puerto Rico.” The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology, vol. 7, no. 3, 2012, pp. 378–403., https://doi.org/10.1080/15564894.2012.729011.

Rodriguez, Yasha N. and Pedro Alvarado Zayas. 2008. "Cueva Lucero." National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. On file at Puerto Rico State Historic Preservation Office at San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Rouse, I. 1992. The Tainos: Rise and Decline of the People Who Greeted Columbus, New Haven: Yale University.

#archaeology#anthropology#cave#cave art#cave paintings#art#rock art#taino#indigenous peoples#pictographs#petroglyphs#colonialism#colonialization#university#school project#blog#puerto rico#grug#monochrome#mountain#caribbean#circles#frog#bird#references#little guys

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

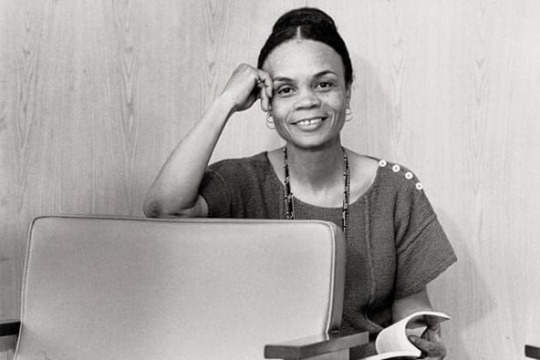

“Sonia Sanchez was born Wilsonia Benita Driver in Birmingham, Alabama. After her mother’s death in 1935 she lived with her grandmother. Her grandmother taught her to read at age four and write at age six. When her grandmother passed away in 1943, she moved to Harlem, New York where she stayed with her father Wilson Driver.

Driver attended Hunter College in New York City where she took creative writing courses although she graduated with a B.A. in Political Science in 1955. Continuing her education at New York University, Driver focused on the study of poetry. She also married and divorced Puerto Rican immigrant Albert Sanchez, although she retained his surname. She later married poet Etheridge Knight and together they had three children. They would later divorce.

In 1965 Sanchez taught at San Francisco State University. The course she offered at San Francisco State in 1966 on the literature of African Americans is generally considered the first of its kind taught at a predominately white university.

Sonia Sanchez released her first collection of poetry in 1969 entitled Homecoming. Her poetry was described at experimental and innovative; Sanchez was the first to blend the musical elements of the blues with the haiku and tanka poetry styles. She tackled many genres of literary art such as writing children’s books, and plays. Sanchez is most famous for her Spoken Word poetry books. She was awarded the American Book Award in 1985 for one of her best-known books, Home girls and Hand grenades.

Sanchez was a major influence in the Black Arts and Civil Rights Movements of the 1960s. She was an active member in the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) as well as the Nation of Islam. She was inspired when she met Malcolm X and used his vernacular in some of her poems. She left the Nation of Islam after three years of affiliation in protest of their mistreatment of women. She continues to advocate for the rights of oppressed women and minority groups.

Sanchez has received countless awards for her work including the P.E.N. Writing Award (1969), the National Academy of Arts Award (1978), and the National Education Association Award (1977-1988). She has guest lectured in over 500 colleges and universities. Her poetry has been heard worldwide in Africa, Australia, Canada, the Caribbean Islands, China, Cuba, Europe, and Nicaragua. Sanchez’s last faculty appointment was at Temple University in Philadelphia where she was the first Presidential Fellow at that institution and the first to hold the Laura Carnell Chair. Sanchez taught courses in English and Women’s Studies until her retirement in 1999.”

Ms. Sanchez now resides in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Good Reads Awards Need To Change

It's time to dissect the 2023 Good Reads Book Awards and the controversy in which it brings.

Sure, these awards might seem like a popularity contest since the winner is decided via public vote but please understand when I say that winning "best book" is very important.

Winning any category for Good Reads isn't just a pat on the back; it's something you can be proud of. You can brag about it, traditional publishing houses might give you a call and it’s also a marketing goldmine, (which is what traditional publishing houses only care about).

In order to win “best book” you need the public to vote for you, which means you need to have fans which also means lesser-known authors are pretty much left in the dust. Even the ones who do get nominated for a category, if there’s another book who had a lot of marketing backing it up, it’s unlikely the one with less advertisement will win.

Authors aren't assembly lines. They can't churn out a new book every year. For many, this year's publication might be their one chance at winning and unless you're blessed with a fanbase the size of George RR Martin's. In a world where about four million books drop annually, doing these awards right and fair is crucial.

So, how do you get it right and what’s wrong with this year nominations? Well, check this out:

In the fiction category, 20 books are up for grabs. Out of 20 authors, you've got...

1 Palestinian (Free Palestine)

1 Puerto Rican

1 Chinese

2 Black authors

The other 15? White.

Representation isn't a checkbox to avoid “cancellation”; it's vital. There are storytellers worldwide, from India to Ukraine, Egypt to Kenya, Cuba, and beyond, with tales to share. But the top 15 authors on this list are white, and only one non-U.S. or non-English POC author made the cut.

Authors from all over the globe published their books this year but can't represent their countries because Good Reads is laser-focused on the American and English demographic which closes the door on unique voices worldwide and is a disservice to literature.

Let's be clear—I've got no beef with these nominated authors. If they're up for best fiction, I assume they wrote a good book. But with 20 choices, most folks will vote for what they've read, likely the one with the flashiest marketing. That puts POC authors at a disadvantage because, let's face it, they're usually broke.

The Good Reads Book Awards needs a change. Keep the popularity contest if you must, but let the real award be decided by a diverse panel of judges who've read every nominated book, cover to cover. Sure, it's not a flawless plan, but it's better than letting popularity and marketing muscle dictate the winner. And let’s make sure the judges aren’t known to the public to avoid any kind of bribes.

To ensure representation, appoint one person from each ethnicity or minority group to represent their book. From the disabled community to LGBTQIA+ (to be fair there was at least one person from this group who made it to the nominee list this year), and definitely an indigenous author here and there—make it not 20 popular fiction books but instead 20 popular diverse voices who wrote a fictional story.

Authors aren't faceless entities; they're individuals craving a spotlight for their stories. If you're asking, "Why aren't there any [blank] authors?" they're out there. You just can't find them because these awards heavily favour a certain kind of author, leaving others, particularly those from minority groups, in the shadows.

May I recommend some First Nation Aboriginal books that came out in 2023 if you would like to diverse your reading? Happy Reading.

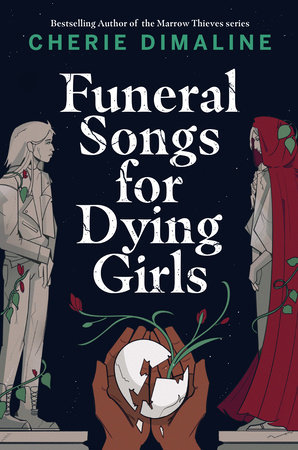

“Funeral Songs for Dying Girls” by Cherie Dimaline follows a young Indigenous girl named Winifred who lives in an apartment above a cemetery. Her father works there in the crematorium, and her mother, who died during childbirth, is buried out in the front yard.

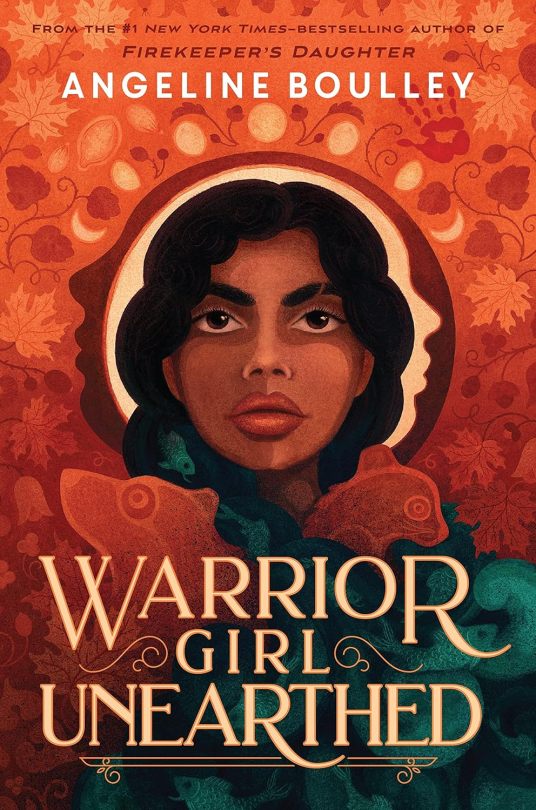

“Warrior Girl Unearthed” by Angeline Boulley: In order to reclaim this inheritance for her people, Perry has no choice but to take matters into her own hands. She can only count on her friends and allies, including her overachieving twin and a charming new boy in town with unwavering morals. Old rivalries, sister secrets, and botched heists cannot—will not—stop her from uncovering the mystery before the ancestors and missing women are lost forever. Sometimes, the truth shouldn't stay buried.

“A Grandmother Begins the Story” by Michelle Porter: Carter is a young mother, recently separated. She is curious, angry, and on a quest to find out what the heritage she only learned of in her teens truly means. Allie, Carter's mother, is trying to make up for the lost years with her first born, and to protect Carter from the hurt she herself suffered from her own mother. Lucie wants the granddaughter she's never met to help her join her ancestors in the Afterlife. And Geneviève is determined to conquer her demons before the fire inside burns her up, with the help of the sister she lost but has never been without. Meanwhile, Mamé, in the Afterlife, knows that all their stories began with her; she must find a way to cut herself from the last threads that keep her tethered to the living, just as they must find their own paths forward.

#writing#writeblr#book#books#good reads#goodreads#Good Reads Awards#indigenous#lgbtqia writers#disabled writer#indigenous writers

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

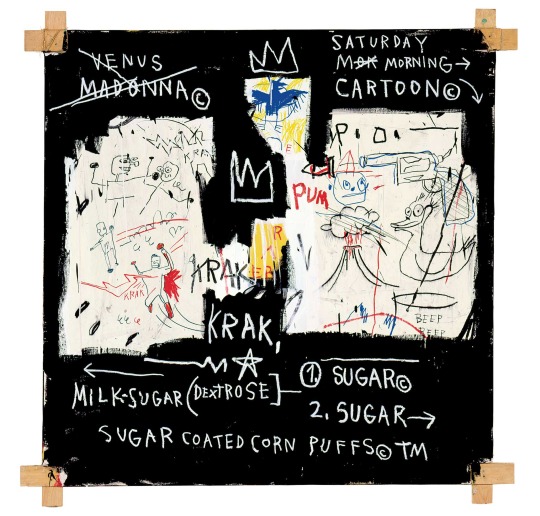

Basquiat: A multidisciplinary artist who denounced violence against African Americans

John Harbour, Université Laval

The exhibition Seeing Loud: Basquiat and Music, currently running at the Montréal Museum of Fine Arts, demonstrates that the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat, which is usually associated with painting, also calls upon other media, including music — the main theme of this exhibition — literature, comic strips, cinema and animation, a much lesser-known aspect of his work.

Basquiat was born in New York in 1960 to a Haitian father and a mother of Puerto Rican descent. In the late 1970s, in collaboration with Al Diaz, he drew enigmatic graffiti under the pseudonym SAMO. The artist quickly made a name for himself in the New York art world (becoming friends with Andy Warhol and Madonna, among others). He then produced solo paintings and achieved international fame that continued to grow until his death in 1988.

At the time of the Black Lives Matter movement, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s work is more relevant than ever. It highlights racial inequalities and the lack of representation of racialized people in the media, but also the violence suffered by African Americans.

Love/hate for the cartoon

As a child, Basquiat dreamed of becoming a cartoon animator. When he became a painter, the television was always on while he worked in his studio, and regularly ran cartoons. These programmes and films were a great source of inspiration for the artist, who integrated several references to animation and comic strips into his paintings.

One of these works, which can be seen in the Montréal Museum of Fine Arts exhibition, is called Toxic (1984). The painting depicts a Black man with his arms in the air, with a collage in the background that mentions several titles of animated shorts made between 1938 and 1948.

Could we say that the films are considered toxic by Jean-Michel Basquiat, despite his admiration for them? In fact, I think there is a certain duality in this picture: the artist loves the cartoon, but he hates it at the same time. The dictionary definition of the word “toxic” can mean someone or something that likes “to control and influence other people in a dishonest way.” The term therefore implies that the toxic element (the cartoon in this case) is dangerous in a way that isn’t apparent.

The violence of cartoons

The cartoon is often associated with childhood, pleasure, eccentricity.

This is a universe where anything is possible: in Gorilla My Dreams, directed by Robert McKimson in 1948, for example, the character Bugs Bunny talks, dresses up as a baby and imitates a monkey. It appears innocent. However, the cartoon can also represent the worst of humanity in a very sneaky way through the incredible violence it contains: the characters hunt each other, chase each other, hit each other, cut each other, kill each other and then start again. https://www.youtube.com/embed/G-fpqSdSnD0?wmode=transparent&start=0 Robert McKimson, Gorilla My Dreams, Warner Bros., 1948.

In Porky’s Hare Hunt, a film directed by Ben Hardaway in 1938 and quoted in Toxic, the character of Porky is injured by dynamite, abused even though he is in his hospital bed and tries to kill a rabbit. Basquiat, who consumed cartoons every day on television, knew that they were a reflection of 20th century American society.

The violence that Basquiat denounces is so present in the cartoon that it seems, to a certain extent, to have become commonplace, like the violence seen on television newscasts (which he probably watched while he was painting).

Denouncing racial stereotypes

These cartoons are also violent because they often perpetuate racial stereotypes (not to mention the many stereotypes related to sexual orientation, gender, sex, body appearance, etc.).

Bob Clampett’s 1940 film Patient Porky, which is also mentioned in Toxic, features a scene in which a elevator attendant grossly and monstrously parodies a Black character. In Untitled (All Stars) (1983), Basquiat cites Max Fleischer’s 1920 film The Chinaman, which features a highly caricatured Asian character and Koko the Clown putting makeup on to impersonate him. https://www.youtube.com/embed/_WXrrOIWZKo?wmode=transparent&start=0 Max Fleischer, The Chinaman, Bray Studios, 1920.

By placing elements referring to animation in his compositions, Basquiat attempts to denounce a stereotypical and unfair worldview where racialized people are portrayed in an unrealistic way. Basquiat said that if he had not been a painter, he would have been a filmmaker and would have told stories where Black people were portrayed as human beings, not negatively.

So, the title of the painting Toxic carries several meanings. It refers both to the main subject (Torrick “Toxic” Ablack), but also to its relationship to popular culture and to animation, in this case.

This hypothesis is very likely since Basquiat produced several works denouncing police brutality against African Americans, including The Death of Michael Stewart (Defacement) (1983).

Basquiat died prematurely in 1988 at the age of 27. Other artists from the Black community, such as Montréal painters Kezna Dalz, aka Teenadult, Manuel Mathieu, and animation filmmaker Martine Chartrand have, in their own way, taken up his struggle and continue to fight for greater visibility of Black people in the arts.

John Harbour, Doctorant en littérature et arts de la scène et de l'écran (concentration cinéma), Université Laval

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

#art#race#jean michel basquiat#basquiat#contemporary art#painting#comics#cartoons#visual art#Black people#African Americans#featured

7 notes

·

View notes