#Hossein Arab

Text

Fantasy booking-the 1st Intercontinental tournament

Rob Faint

We all know the story of how Pat Patterson won the IC title back in 1979. The story is he won the title in a fictitious tournament in Rio De Janeiro, Brazil. My question is, why did the WWF not run a real tournament? Who would have been the participants? In this column I attempt to book the tournament acknowledging Patterson as the eventual winner.

Continue reading Untitled

View On WordPress

#Bad News Allen#Chief Jay Strongbow#Ernie Ladd#Fantasy Booking#Greg Valentine#Haystacks Calhoun#Hossein Arab#Intercontinental Title#Ivan Putski#Larry Zbyszko#Pat Patterson#Rio de Janeiro#Ted Dibiase#The Boogie Woogie Man Jimmy Valiant#Tito Santana#WWE#WWF#WWWF

0 notes

Photo

HOSSEIN ZENDEROUDI 1970s

196 notes

·

View notes

Text

Live coverage of the 18th of October has now begun.

Iran's Foreign Minister calls for the world to unite against Israel in the aftermath of the bombing of Al-Ahli Arab Hospital

#gaza#free gaza#gaza strip#palestine#free palestine#news on gaza#irish solidarity with palestine#al jazeera#Iran#Iranian Foreign Minister#hossein amir abdollahian#Israel#Boycott Israel#War crimes#Al-Ahli Arab Hospital

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Syrian President Bashar al-Assad meeting Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi and his delegation in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia today, 11 November 2023

#Assad#Bashar al-Assad#Syria#Ebrahim Raisi#Hossein Amir-Abdollahian#Hossein Amirabdollahian#Iran#Raisi and MbS met so that's kinda a big deal#Riyadh#Saudi Arabia#Arab Summit#Arab and Islamic Countries Summit#Gaza#Gaza Strip#Palestine

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yemeni, Iranian, and Palestinian authorities have spoken out in support of US university students and faculty members who have been targeted by brutal police repression for the past two weeks during mobilizations calling for an end to the genocide in Gaza. The leader of Yemen's ruling Ansarallah movement, Abdul Malik al-Houthi, said during a speech on 25 April that the US government “does not respect their laws, their constitution, or any headlines they raise and brag about,” stressing that there is a “concerted effort” from Washington to silence a movement that “has begun to wake up to the horror of what is happening in occupied Palestine.”

“With the demonstrations and sit-ins at prominent US universities, the US support for the Israeli enemy became clear, as authorities dealt with the demonstrations and protests … in a bad manner that goes beyond all considerations,” the Yemeni resistance leader added.

Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian also condemned the crackdown witnessed across several universities.

“The suppression and violent treatment of the American police and security forces against professors and students protesting the genocide and war crimes of the Israeli regime in various universities of the United States is deeply worrying,” Iran's top diplomat said via social media, adding that this repression is an extension of “Washington's full-fledged support for the Israeli regime and clearly shows the double standard policy and contradictory attitude of the American government towards freedom of expression.”

In Palestine, officials from Hamas and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), as well as student organizations in the Gaza Strip, issued statements supporting the grassroots movement that has taken over about two dozen university campuses in the US.

“We, the students of Gaza, salute the students of Columbia University, Yale University, New York University, Rutgers University, the University of Michigan, and dozens of universities across the United States who are rising in solidarity with Gaza and to put an end to the Zionist–US genocide against our people in Gaza,” a statement from students organizations in Gaza reads.

“From here in Gaza, we see you and salute you. Your actions and activism matter, especially in the heart of the empire, in the United States … It is clear that a new generation is rising that will no longer accept Zionism, racism, and genocide and that stands with Palestine and our liberation from the river to the sea,” the statement adds.

For their part, the PFLP called on Palestinian and Arab students to “rise for Gaza following the example of American universities.”

“Palestinian and Arab universities must take the initiative and break the barrier of silence, following the example of American universities which have ignited an intifada within the campus for the victory of the blood of our Palestinian people, and in rejection of the continuing American support for the zionist entity,” the PFLP statement reads.

In a similar vein, Hamas politburo member Izzat al-Rishq said that the government of US President Joe Biden “violates individual rights and the right to expression, and arrests university students and faculty members because they reject the genocide that our Palestinian people are subjected to in the Gaza Strip at the hands of the neo-Nazi Zionists, without the slightest feeling of shame about the legal value represented by the students and university professors.”

“The Biden administration, which is a partner in the brutal war on our Palestinian people, does not want to acknowledge that [the US public has] discovered the truth about the Nazi entity and is siding with human values and standing on the right side of history. Today’s students are the leaders of the future, and their suppression today means an expensive electoral bill that the Biden administration will pay sooner or later.”

#yemen#jerusalem#tel aviv#current events#palestine#free palestine#gaza#free gaza#news on gaza#palestine news#news update#war news#war on gaza#students for justice in palestine#gaza solidarity encampment#columbia university#iran#pflp#palestinian resistance

529 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi i saw your post on Iranian names being replaced by Arabic ones and I didn't know that happened. Do you have more information or examples? Is it people's first names or roads/streets or something else?

Of course, thank you for asking. I'm sure you're familiar with names such as "Ali" and "Mohammad" and "Hossein". These are Arabic origin names, not Iranian. Iranian names are names such as "Hushang", "Koroush" and "Anahita".

So why do so many Iranians have Arabic names? That goes back to history, around 600-700 AD where the Iranian Sassanian empire fell and was invaded ruthlessly by the Arabs. The Arabs brought with them Islam and made everyone convert to this religion. Persian language was almost lost, and everyone was speaking Arabic. It was thanks to Ferdowsi and the Iranian intermezzo that Iran revived the Persian language and did not lose its native tongue to Arabic like North Africa has.

Unfortunately, Arabic names are still very common in Iran. You can also see a lot of Arabic names in South Asia due to colonisation and invasion. Persian language also unfortunately still has some Arabic words in it, so it isn't pure.

What I meant to say with that post is I want these Arabic names gone and replaced with authentic Iranian names to bring back the real and pure Iranian culture.

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

🟠 Monday - ISRAEL REALTIME - Connecting to Israel in Realtime

▪️INTL POLITICS.. Hossein al-Sheikh, secretary general of the PLO working committee and designated to succeed PA 4-year president for life Abu Mazen, met today in his office in Ramallah with the new British foreign minister. A-Sheikh demanded that Britain act for "the cessation of aggression on Gaza, the introduction of aid and for the return of the Palestinian Authority to the Gaza Strip, “and the recognition of a Palestinian state.

▪️IRAN CLAIMS.. that Israel is operating a spy balloon on the Iran-Azerbaijan border in order to gather information.

▪️IDF MILITARY EXERCISE.. Jordan Valley. Expected military movements.

▪️LEBANON EXPLOSION.. Wadi Khaled, northern Lebanon, on the border with Syria: a huge gas explosion. Unknown reason.

▪️ECONOMY.. Google in talks to buy an Israeli cyber company “Wiz” for $23 billion. If it closes it will be Google’s largest acquisition, and Israel’s largest hi-tech exit.

▪️SOCIETY.. Significant increase in the recruitment of ultra-Orthodox youth for nationalservice. Since the beginning of the war, twice as many ultra-Orthodox have been joined national service than last year. This year, 813 ultra-Orthodox volunteers joined compared to 492 last year. A total of 1,538 ultra-Orthodox members serve, among others, in security agencies such as the Shin Bet, Mossad, and the Israel Police, as well as in educational, management, and other positions.

The numbers put them in line with their percentage among the population. 12,033 are from the Jewish general society, 5,356 are servants from the Arab and Druze sector and 1,938 are from special populations.

▪️CORONA IS UP.. a wave of Corona is going through Israel. For the vast majority it is “just a flu”, but almost 100 are hospitalized with serious cases, 15 very serious (which is not a huge number - and similar to serious flu cases in the winter). Doctors are complaining that the drugs to treat serious Corona are not covered by the Israeli health basket, and therefore of highly limited availability.

▪️HIGH COURT ORDERS PAID DEFENSE ATTORNEYS FOR TERRORISTS.. which outraged many in the Knesset, but the reason: a Knesset law on terrorist handling that says - Section 15 of the law states that "the hearing will be held in the presence of the detainee's defense counsel and if he is not represented, the court will appoint him defense counsel”.

♦️HEAVY IDF BOMBING in Gaza overnight, as well as many sites in Lebanon targeted overnight.

♦️COUNTER-TERROR OPS - TURMOS AYA.. Ramallah area.

⭕ INTERCEPTION OVER HAIFA.. explosion, rocket trail photo’d.

⭕ INFILTRATION? ALMON.. There was a Home Front alert for an Infiltration in the Samaria town of Almon (north west of Jerusalem) at 6:30 AM, but I’ve seen no follow up either of an attack or of clearing the incident.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Arab News is Saudi Media]

[The New Arab is Saudi Media]

Members of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) should impose an oil embargo and other sanctions on Israel and expel all Israeli ambassadors, Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian said on Wednesday.

18 Oct 23

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gli oltre sette mesi di massacri nella Striscia di Gaza hanno il volto di un intero territorio cancellato, di più di 35mila persone uccise di cui oltre un terzo minorenni, di quasi 80mila feriti e di oltre un milione e mezzo di sfollati. Il volto di un genocidio consumato sotto gli occhi di tutti e che nessuno, tra chi ne avrebbe l’autorità, può o vuole interrompere. Anche se l’operazione israeliana sta generando ripercussioni profondissime su tutto il Medio Oriente.

Vista attraverso gli occhi dei paesi dell’area l’immagine si allarga e rende un quadro intricatissimo dalle mille sfaccettature. Dal rafforzamento delle formazioni che rappresentano il cosiddetto «Asse della Resistenza» al rischio di un’implosione di paesi come Libano ed Egitto, dalla destabilizzazione delle rotte commerciali in uno dei principali snodi marittimi mondiali ai mutamenti politici in seno a quella che viene definita la «Mezzaluna sciita». Il 7 ottobre del 2023 non ha cambiato soltanto il volto di Gaza o della Palestina, ma dell’intera regione.

[...]

È evidente che, escluso l’elefante nella stanza rappresentato dall’Iran, Libano, Siria, Yemen ed Egitto sono i paesi su cui la crisi in atto ha maggiori ripercussioni e al contempo quelli che hanno un impatto maggiore sulle dinamiche mediorientali. Tuttavia, non sono i soli. Soprattutto non è scontato che le cose rimarranno così. La volatilità degli avvenimenti a cui stiamo assistendo, infatti, è estrema: prova ne sia la morte pochi giorni fa del presidente della Repubblica iraniana Ebrahim Raisi e del ministro degli esteri Hossein Amir-Abdollahian, che porterà l’Iran al voto di qui a poche settimane.

Ciò a cui stiamo assistendo è l’apertura (o meglio, la conferma sul campo) di una nuova fase per il Medio Oriente. Una fase che arriva dopo il tentativo di «normalizazione» a suon di guerre made in Usa di inizio secolo, dopo l’epoca delle primavere arabe, dopo quella della «pax israeliana» attraverso l’ombrello militare di Abramo. Una fase che certifica la morte di ogni prospettiva per così dire concertativa, basata cioè sulle relazioni e sul diritto internazionale. Una fase che al momento vede l’ascesa del cosiddetto «Asse della resistenza» sciita come unica forza in grado di portare una visione un minimo più larga dell’interesse singolo di ciascuno Stato, nell’incapacità dell’Unione europea di smarcarsi da una politica atlantica che da decenni allontana inesorabilmente le tre sponde del Mediterraneo.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Sunday, Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi and several other officials, including Foreign Minister Hossein Amirabdollahian, died in a helicopter crash. This incident occurred following an unprecedented round of escalation between Iran and Israel in April, sparking speculation on the potential implications for Iran’s regional policy and the ongoing conflict with Israel.

Despite the sudden vacuum that has emerged at the top of Iran’s executive branch, the strategic direction of its foreign and regional policies, primarily determined by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and influenced by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), are expected to remain unaltered. However, the recent escalation between Iran and Israel is already impacting Iran’s strategic thinking and its regional calculations.

For Iran, Israel’s April 1 attack on the Iranian embassy compound in Damascus that killed several IRGC members, including high-level commanders, crossed a line. From its vantage point, both the targets’ seniority and the facility’s character represented an unacceptable Israeli escalation.

As an immediate matter, Tehran believed that leaving unanswered an attack on what it considers equivalent to sovereign territory could lead Israel to target more Iranian officials on Iranian territory. But perhaps more importantly, Iranian officials likely perceived the Damascus attack as the latest way station toward a bigger objective: an Israeli incursion into Lebanon aimed at cutting off Hezbollah’s logistical support.

Israel’s killing of Brig. Gen. Razi Mousavi outside Damascus in December eliminated the Iranian chief of logistics in charge of supporting Iran’s nonstate allies in the Levant; a similar attack in January removed the IRGC’s intelligence chief in Syria; and taking out Gen. Mohammed Reza Zahedi on April 1 eliminated the chief of operations in that area.

Iran also needed to save face at home and among its regional allies. After the April strike in Damascus, some hard-liners started openly criticizing the leadership. Tehran thus felt it had to react with force, but needed to restore a degree of deterrence without triggering a war.

It squared the circle by conducting a highly telegraphed but massive drone and missile strike on Israel in the early hours of April 14. The priority was not death and destruction—though the scale of the attack risked both—but demonstrating that it dared to strike Israeli territory directly. Tehran likely chose which parts of its capabilities to expose while at the same time gathering significant intelligence on Israeli and U.S. defensive capabilities.

The commander of the IRGC’s aerospace force suggested that Iran deployed less than 20 percent of the capacities that it had prepared for the operation, whereas Israel, helped by the United States and other allies, had to mobilize its full defensive arsenal. If these claims are even remotely accurate, it raises questions over whether the successful defense could be replicated were Iran to mount an even more significant barrage using more advanced weapons, especially one that comes as a surprise and continues over an extended period of time.

While Israel and its partners largely succeeded in neutralizing the attack, Tehran boosted its standing among its supporters, and perhaps its reputation as an avowed defender of Palestinian rights on the Arab street as well. It achieved all this without distracting international attention from the horrors of the war in Gaza—a fact further highlighted by the pro-Palestinian protests on university campuses in the United States and some European countries.

From this perspective, the attack’s success came not from its limited military achievement but from the very fact that it directly targeted a powerful adversary backed by an even more powerful superpower. As Khamenei has contended, the key signal that Iran sent to Israel was Tehran’s high tolerance for risk, which aims to deter Israel from future operations aimed at decapitating the Iranian military and cutting off its hand in the Levant.

Yet the red line set by the IRGC’s chief commander immediately following the strike—that any attack anywhere on any Iranian target would be cause for another direct Iranian attack on Israel—was quickly shown to be an empty threat in light of Israel’s subsequent strike in Isfahan on April 19 local time, carried out with an air-to-surface missile strike from Iraqi airspace on an S-300 missile defense system’s radar, near sensitive nuclear facilities in Natanz.

A return to a status quo ante shadow war is probably an acceptable outcome for Iran. From Tehran’s perspective, it would at best find a way to limit the scope of Israel’s mabam (“war within the wars”) campaign of targeting Iranian arms shipments and facilities in Syria. At a minimum, Iran hopes to put an end to Israel’s targeting of senior Iranian commanders and its humiliating covert operations on Iranian soil. It is too early to determine if Iran can achieve any of these objectives.

A key question now is how the bilateral rivalry fits into the wider regional picture. While Israel and the United States could boast that they activated an ad hoc regional cooperation with Arab states to intercept the salvo of projectiles, the Arab states involved were keen not to be named or seen as taking sides. Contrary to the Israeli attempt to frame Arab states’ actions as signaling the emergence of an anti-Iran regional alliance that would benefit it, Arab leaders instead saw proof of what they have long feared might happen: that tensions between Israel and Iran could put them in the crossfire.

Iranian leaders seem convinced that their retaliation, which did not even include the tip of their regional spear, Hezbollah, successfully mitigated the possibility of further escalation—for now. That defending Israel against an Iranian strike cost upward of $1 billion and required a major team effort involving at least five countries versus a $200 million price tag for Iran implies that neither Israel nor the U.S. seeks additional rounds of fighting. Iran thus has a window to focus on the lessons learned, just as Israel and the U.S. military are likely doing the same.

Despite the Iranian assertion of having pulled its punches, U.S. officials assess that the goal “clearly was to cause significant damage and deaths”—in which case those punches failed to land. This appears to be the result of both offensive vulnerabilities and defensive strengths, as Iranian drones traveling long distances were detected in near-real time, many of the projectiles were intercepted before even reaching Israeli territory, and a significant percentage—perhaps as many as half—of the ballistic missiles reportedly failed of their own accord.

To correct for these failings, Iran may seek to bolster the development and stockpiling of arms closer to Israel, necessitating a deepened presence in Syria, as well as to redouble the development of more advanced missiles—including hypersonic missiles—as part of any future strike package.

Israel’s retaliation was a reminder to Iranian leaders that Israel has the capability to do significant harm to Iran’s nuclear facilities. It also exposed Tehran’s principal shortcomings—its lack of more capable air defense systems like the S-400, as well as Israel’s essentially unchallenged ability to penetrate neighboring airspaces. To address the former, Tehran is likely to redouble efforts to obtain advanced Russian weaponry in exchange for ballistic missiles, even if doing so would further damage Iran’s relations with Europe.

Addressing the latter shortcoming could also cause it to look for help from Russia, especially in Syria; but in Iraq, the U.S. military stands in the way, which is likely to further motivate Iran to try to evict the nearly 2,500 U.S. forces from Iraq by encouraging its allied militias to continue targeting U.S. bases and ramping up political pressure on the Iraqi government.

Tehran is also likely to intensify efforts aimed at loosening the already precarious hold of the U.S.-allied, Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces on territory east of the Euphrates River in Syria. This could give Iran more land access points to Syria (and to Lebanon beyond), while strengthening its influence on the river’s western bank in Deir ez-Zor province. Finally, Tehran will also likely focus on addressing repeated intelligence failures that have exposed its senior commanders abroad and rendered it vulnerable at home.

Iran’s leadership believes that the capabilities it has demonstrated since October—the asymmetric warfare capacity of its regional partners as well as the enduring image of Iranian warheads soaring over Israeli skies—could, together with the Gaza conflict’s fallout, portend a regional reordering.

In Tehran’s eyes, Israel will become increasingly ostracized globally; the United States will no longer be the region’s most pivotal player as other powers like Russia, China, and India extend their influence; and the Gulf Arab states will steer clear of banding together against Iran, instead seeking to improve their relations with Iranian allies such as Syria and Hezbollah.

The Iranian leadership complement this vision with a desire to consolidate Iran’s status as a threshold nuclear weapons state that could in short order develop a nuclear warhead, which would complicate any future deal aimed at significantly rolling back Iran’s nuclear capabilities, especially given Tehran’s cynicism about the West’s ability to deliver effective and sustainable sanctions relief.

Yet Iranian leaders may find that enduring realities will undermine their bullish narrative and bring both short- and medium-term risks. Given that Iran and Israel have yet to fully define and test any new rules of the game, both may miscalculate, especially because those in Tehran who believe that Iran should abandon its vaunted strategic patience and replace it with a more aggressive posture appear to be ascendant. These hard-liners believe that Israel will soon test Iran’s willingness to stand firm on its red lines, and that if Tehran fails to do so, the returns from the massive risk it took on April 14 will be lost.

That increases the risk of miscalculation on both sides and could lead to an escalatory cycle that could be devastating. In the medium term, what Iran sees as the beginning of an emerging new order to replace a vanishing Pax Americana in the Middle East could instead push Gulf Arab states to double down on their request for stronger U.S. security assurances, and this in turn is bound to deepen Tehran’s perception of the threats it faces.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

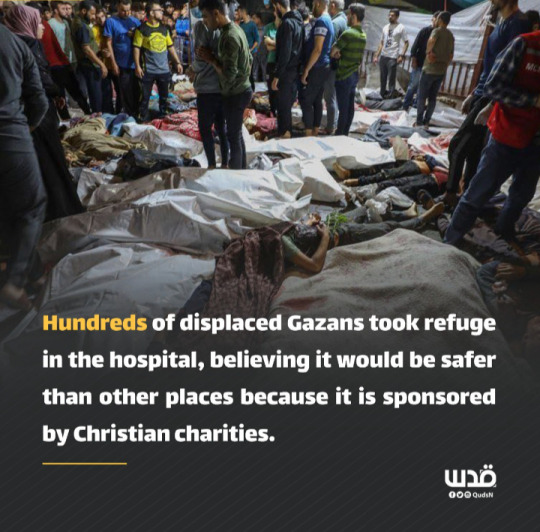

🇮🇱🇵🇸 💥ISRAELI FORCES BOMB GAZA HOSPITAL KILLING 500 CIVILIANS, MOSTLY WOMEN AND CHILDREN💥

Israeli Occupation Forces launched an air strike Tuesday targeting al-Ahli Babtist hospital in Gaza City, killing upwards of 500 civilians with hundreds more severely wounded, mostly women and children according to the Gaza Health Ministry.

The Gaza Health Ministry said in statement Israeli air strikes on the Gaza City Baptist hospital killed hundreds of civilians who were sheltering and receiving aid inside, along with the medical staff, doctors and aid workers inside.

"Hundreds of victims are still under the rubble," the Ministry said.

According to the Palestinian Civil Defense, Tuesday's air strike was the deadliest by Israel against Palestinian civilians in five wars fought since 2008.

“The massacre at al-Ahli Arab Hospital is unprecedented in our history. While we’ve witnessed tragedies in past wars and days, but what took place tonight is tantamount to genocide,” spokesman Mahmoud Basal said.

"The hospital was housing hundreds of sick and wounded, and people forcibly displaced from their homes" because of other strikes, a statement said.

The Palestine Red Crescent Society (PRCS) publicly condemned the Israeli attack as genocide.

Iran's Foreign Minister, Hossein Amir-Abdollahian wrote a message on the social media platform X calling Global leaders to put an end to Israeli War Crimes.

"After the terrible crime of the Zionist regime in the bombing and massacre of more than a thousand innocent women and children in the al-Moamadani Hospital, the time has come for the global unity of humanity against this fake regime more hated than ISIS and its killing machine. TIME IS OVER."

Al-Mayadeen English posted to Twitter, "The Israeli Occupation deliberately bombed al-Maamadani Hospital in the Gaza strip with the death toll expected to reach over 800."

Iran's Foreign Ministry spokesperson, Nasser Kan'ani condemned the attack on civilians as a brutal act of war, crime and genocide.

"The Zionist regime... by committing this heinous and atrocious crime, once again revealed its savagery and inhumanity to the world and proved that it has no slightest adherence to the principles and rules of international law during times of war," he said.

Tens of thousands of Palestinians are currently sheltering in schools and hospitals who had hoped to be spared from the bombing, but in the end, the Zionist regime targeted them even there.

#WarCrimes #CrimesAgainstHumanity

#source1

#source2

@WorkerSolidarityNews

#palestine#palestine news#palestinians#free palestine#gaza#gaza strip#gaza news#free gaza#israel#israel news#israeli apartheid#israeli war crimes#israeli occupation#war crime#war crimes#crimes against humanity#war#news#politics#geopolitics#war news#world news#global news#international news#hamas#al aqsa flood#al aqsa storm#israel war#gazaunderattack#WorkerSolidarityNews

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

DUBAI, United Arab Emirates (AP) — A helicopter carrying Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi, the country’s foreign minister and other officials apparently crashed in the mountainous northwest reaches of Iran on Sunday, sparking a massive rescue operation in a fog-shrouded forest as the public was urged to pray.

The likely crash came as Iran under Raisi and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei launched an unprecedented drone-and-missile attack on Israel last month and has enriched uranium closer than ever to weapons-grade levels.

Iran has also faced years of mass protests against its Shiite theocracy over an ailing economy and women’s rights — making the moment that much more sensitive for Tehran and the future of the country as the Israel-Hamas war inflames the wider Middle East.

Raisi was traveling in Iran’s East Azerbaijan province. State TV said what it called a “hard landing” happened near Jolfa, a city on the border with the nation of Azerbaijan, some 600 kilometers (375 miles) northwest of the Iranian capital, Tehran. Later, state TV put it farther east near the village of Uzi, but details remained contradictory.

Traveling with Raisi were Iran’s Foreign Minister Hossein Amirabdollahian, the governor of Iran’s East Azerbaijan province and other officials and bodyguards, the state-run IRNA news agency reported. One local government official used the word “crash,” but others referred to either a “hard landing” or an “incident.”

Neither IRNA nor state TV offered any information on Raisi’s condition in the hours afterward. However, hard-liners urged the public to pray for him. State TV later aired images of the faithful praying at Imam Reza Shrine in the city of Mashhad, one of Shiite Islam’s holiest sites, as well as in Qom and other locations across the country. State television’s main channel aired the prayers nonstop.

“The esteemed president and company were on their way back aboard some helicopters and one of the helicopters was forced to make a hard landing due to the bad weather and fog,” Interior Minister Ahmad Vahidi said in comments aired on state TV. “Various rescue teams are on their way to the region but because of the poor weather and fogginess it might take time for them to reach the helicopter.”

IRNA called the area a “forest” and the region is known to be mountainous as well. State TV aired images of SUVs racing through a wooded area and said they were being hampered by poor weather conditions, including heavy rain and wind.

A rescue helicopter tried to reach the area where authorities believe Raisi’s helicopter was, but it couldn’t land due to heavy mist, emergency services spokesman Babak Yektaparast told IRNA.

Long after the sun set, Iranian government spokesman Ali Bahadori Jahromi acknowledged that “we are experiencing difficult and complicated conditions” in the search.

“It is the right of the people and the media to be aware of the latest news about the president’s helicopter accident, but considering the coordinates of the incident site and the weather conditions, there is ‘no’ new news whatsoever until now,” he wrote on the social platform X. “In these moments, patience, prayer and trust in relief groups are the way forward.”

Khamenei himself also urged the public to pray.

“We hope that God the Almighty returns the dear president and his colleagues in full health to the arms of the nation,” Khamenei said, drawing an “amen” from the audience he was addressing.

Raisi, 63, a hard-liner who formerly led the country’s judiciary, is viewed as a protégé of Khamenei and some analysts have suggested he could replace the 85-year-old leader after Khamenei’s death or resignation from the role.

Raisi had been on the border with Azerbaijan early Sunday to inaugurate a dam with Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev. The dam is the third one that the two nations built on the Aras River. The visit came despite chilly relations between the two nations, including over a gun attack on Azerbaijan’s Embassy in Tehran in 2023, and Azerbaijan’s diplomatic relations with Israel, which Iran’s Shiite theocracy views as its main enemy in the region.

Iran flies a variety of helicopters in the country, but international sanctions make it difficult to obtain parts for them. Its military air fleet also largely dates back to before the 1979 Islamic Revolution. IRNA published images it described as Raisi taking off in what resembled a Bell helicopter, with a blue-and-white paint scheme previously seen in published photographs.

Raisi won Iran’s 2021 presidential election, a vote that saw the lowest turnout in the Islamic Republic’s history. Raisi is sanctioned by the U.S. in part over his involvement in the mass execution of thousands of political prisoners in 1988 at the end of the bloody Iran-Iraq war.

Under Raisi, Iran now enriches uranium at nearly weapons-grade levels and hampers international inspections. Iran has armed Russia in its war on Ukraine, as well as launched a massive drone-and-missile attack on Israel amid its war against Hamas in the Gaza Strip. It also has continued arming proxy groups in the Mideast, like Yemen’s Houthi rebels and Lebanon’s Hezbollah.

Meanwhile, mass protests in the country have raged for years. The most recent involved the 2022 death of Mahsa Amini, a woman who had been earlier detained over allegedly not wearing a hijab, or headscarf, to the liking of authorities. The monthslong security crackdown that followed the demonstrations killed more than 500 people and saw over 22,000 detained.

In March, a United Nations investigative panel found that Iran was responsible for the “physical violence” that led to Amini’s death.

President Joe Biden was briefed by aides on the Iran crash, but administration officials have not learned much more than what is being reported publicly by Iran state media, said a senior administration official, who was not authorized to comment publicly and spoke on condition of anonymity.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who was the founder of the first central government in Iran?

The founder of the first central government in Iran dates back to the Achaemenid period by Cyrus the Great. Achaemenid Cyrus was crowned in 550 BC and established the first central government in Iran.

The origin of the name Iran

The country of Iran was not called "Iran" from the beginning and was known by the names of Persia, Pars and Pers among others. Saeed Nafisi suggested the word "Iran" instead of "Persia" in January 1313 AH. The naming initially caused opposition. Because the politicians considered "Persia" as an international name that was familiar among all types. The supporters of this naming also considered the term "Iran" as the best name to describe the political authority and cultural background of this country.

In 1314 AH, based on the circular of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Iran and the request of the then government of Reza Shah, the word "Iran" was officially used to name the country and replace other names. Professor Arthur Upham Pope, an American Iranologist, writes in the book Masterpieces of Iranian Art translated by Parviz Natal Khanleri:

The word "Iran" was used for the plateau and geographical functions of Iran in the first millennium BC.

According to Mohammad Moin, the great Iranian writer, the origin of the word "Arya" is so clear that the eastern part of Indo-Europe considers themselves proud of this name. Indo-Iranian common ancestors also introduced themselves with this name and named their country as "Iran-Oejah".

Pre-Islamic era in Iranian history

The pre-Islam era, which includes various events in the history of Iran, includes the time period before the arrival of the Aryans, that is, the rule of Elam until the end of the Sassanid rule and the arrival of the Arabs in Iran. According to historical sources, before the Aryans entered Iran, the Elamites lived as a native dynasty in the Iranian plateau.

The Elam dynasty was formed in the southwestern region of the Iranian plateau around 3,000 years BC, and they named their territory "Hatmati". The rule of Elam expanded during the period of the famous kings of this dynasty, and they dominated parts of Mesopotamia (Mesopotamia) in addition to southwestern Iran.

Whenever the Elamites gained more power, they played an important role in the Middle River politics. They overcame Sumer around 2,000 BC and completely subjugated the Mesopotamia. Historians divide the political history of Elam into three periods:

Ancient Elam, Middle Elam and New Elam

The migration of Aryans to the Iranian plateau

In the third period of the rule of Elam, the Medes, as a group of Aryans, established their power in the northwest of Iran and took control of that part of Iran. The Parthians (Ashkanians) and the Persians (Achaemenians and their successors, who were called the Sasanians) were two other Aryan tribes who formed a government in the Iranian plateau after the Medes.

There are many theories about the ethnicity, race and migration of Aryans and their entry into Iran, which are the source of disagreement among scholars and have not yet reached a single conclusion about them. Some consider Siberia as the origin of Aryans and believe that they entered the Iranian plateau from there.

The post-Islam era in Iranian history

Yazdgerd III, the last Sassanid king, was defeated by the Arabs and left Iran to them. "Rostam Farrokhzad" was defeated by the Arabs in the battle of Qadisiyah (636 AD) and lost his life despite his bravery. He organized his forces and was defeated by the Arabs in the war that took place in Nahavand (642 AD). Yazdgerd fled to the East with his family and was killed near Merv. With the death of Yazdgerd III, his empire fell in 651 AD.According to the book "Two Centuries of Silence" by "Abd al-Hossein Zarinkoub", some Iranians were not satisfied with the arrival of Arabs in the country and continued to adhere to the Zoroastrian religion. Zoroastrian Iranians paid tribute to music during this period. According to Zarinkoob, Iranians do not accept Islam with open arms and during this time, they were fighting with the Arabs in the corners and sides of Iran in order to advance them. On the other hand, Shahid Motahari criticized Zarinkoub in his book "Mutual Services of Islam and Iran" and did not consider his opinion to be scientific. He believes that Iranians accepted Islam with open arms.

The land of Iran gradually surrendered to the Arabs and only Tabaristan and Gilan maintained their independence by resisting. During this period, government powers did not rule in Iran and local governments have power in some parts of Iran.

The domination of Arabs over Iran caused their culture to be revealed in Iran, and with the beginning of independent Islamic governments in Iran, the Hijri lunar calendar, the foundations of historians in writing the history of Iran, was published.

contemporary history

World War II brought chaos to Iran and Reza Shah resigned from the throne. Mohammad Reza succeeded his father in 1320 AH (1941 AD). The creation of the 14th Parliament, the nationalization of the oil industry, the withdrawal of Soviet forces from Iran after the end of World War II, the August 28 coup, the Baghdad Pact, and the formation of the Iranian National Front were among the most important events of this period.

With the formation of the Islamic Revolution in 1357 AH (1978 CE), the life of Pahlavi rule ended and the Islamic Republic replaced it.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The death of Mahsa Amini on 16 September 2022, while in police custody for wearing an “improper” hijab, has triggered what has become the most severe and sustained political upheaval ever faced by the Islamist regime in Iran. Waves of protests, led mostly by women, broke out immediately, sending some two-million people into the streets of 160 cities and small towns, inspiring extraordinary international support.1 The Twitter hashtag #MahsaAmini broke the world record of 284 million tweets, and the UN Human Rights Commission voted on November 24 to investigate the regime’s deadly repression, which has claimed five-hundred lives and put thousands of people under arrest and eleven hundred on trial. The regime’s suppression and the opponents’ exhaustion are likely to slow down the protests, but unlikely to end the uprising. For political life in Iran has embarked on an uncharted and irreversible course.

How do we make sense of this extraordinary political happening? This is neither a “feminist revolution” per se, nor simply the revolt of Generation Z, nor merely a protest against the mandatory hijab. This is a movement to reclaim life, a struggle to liberate free and dignified existence from an internal colonization. As the primary objects of this colonization, women have become the major protagonists of the liberation movement.

About the Author

Asef Bayat is professor of sociology, and Catherine and Bruce Bastian Professor of Global and Transnational Studies at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. His latest books include Revolutionary Life: The Everyday of the Arab Spring (2021).

View all work by Asef Bayat

Since its establishment in 1979 Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s, the Islamic Republic has been a battlefield between hardline Islamists who wished to enforce theocracy in the form of clerical rule (velayat-e faqih), and those who believed in popular will and emphasized the republican tenets of the constitution. This ideological battle has produced decades of political and cultural strife within state institutions, during elections, and in the streets in daily life. The hardline Islamists in the nonelected institutions of the velayat-e faqih have been determined to enforce their “divine values” in political, social, and cultural domains. Only popular resistance from below and the reformists’ electoral victories could curb the hardliners’ drive for total subjugation of the state, society, and culture.

For two decades after the 1990s, elections gave most Iranians hope that a reformist path could gradually democratize the system. The 1997 election of the moderate Mohammad Khatami as president, following a notable social and cultural openness, was seen as a hopeful sign. But the hardliners saw the reform project as an existential threat to clerical rule, and they fought back fiercely. They sabotaged Khatami’s government, suppressed the student movement, shut down the critical press, and detained activists. After 2005, they went on banning reformist parties, meddling in the polls, and barring rival candidates from participating in the elections. The Green Movement—protesting the fraud against the reformist candidate Mir Hossein Mousavi in the 2009 presidential election—was the popular response to such a counterreform onslaught.

The Green revolt and the subsequent nationwide uprisings in 2017 and 2019 against socioeconomic ills and authoritarian rule profoundly challenged the Islamist regime but failed to alter it. The uprisings caused not a revolution but the fear of revolution—a fear that was compounded by the revolutionary uprisings against the allied regimes in Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq, which Iran helped to quell.2 Against such critical challenges, one would expect the Islamist regime to reinvent itself through a series of reforms to restore hegemony. But instead, the hardliners tightened their grip on political power in a bid to ensure their unrestrained hold over power after the supreme leader expires. Thus, once they took over the presidency in 2021 and the parliament in 2022 through rigged elections—specifically, through the arbitrary vetoing of credible rival candidates—the hardliners moved to subjugate a defiant people once again. Extending the “morality police” into the streets and institutions to enforce the “proper hijab” has been only one measure—but it was the one that unleashed a nationwide uprising in which women came to occupy a central place.

Women did not rise up suddenly to spearhead a revolt after Mahsa Amini’s death. Rather, it was the culmination of years of steady struggles against a systemic misogyny that the postrevolution regime established. When that regime abolished the relatively liberal Family Protection Laws of 1967, women overnight lost their right to initiate divorce, to assume child custody, to become judges, and to travel abroad without the permission of a male guardian. Polygamy came back, sex segregation was imposed, and all women were forced to wear the hijab in public. Social control and discriminatory quotas in education and employment compelled many women to stay at home, take early retirement, or work in informal or family businesses.

A segment of Muslim women did support the Islamic state, but others fought back. They took to the streets to protest the mandatory hijab, organized collective campaigns, and lobbied “liberal clerics” to secure a women-centered reinterpretation of religious texts. But when the regime extended its repression, women resorted to the “art of presence”—by which I mean the ability to assert collective will in spite of all odds, by circumventing constraints, utilizing what exists, and discovering new spaces within which to make themselves heard, seen, felt, and realized. Simply, women refused to exit public life, not through collective protests but through such ordinary things as pursuing higher education, working outside the home, engaging in the arts, music, and filmmaking, or practicing sports. The hardship of sweating under a long dress and veil did not deter many women from jogging, cycling, or playing basketball. And in the courts, they battled against discriminatory judgments on matters of divorce, child custody, inheritance, work, and access to public spaces. “Why do we have to get permission from Edareh-e Amaken [morality police] to get a hotel room, whereas men do not need such authorization?” a woman wrote in rage to the women’s magazine Zanan in 1988.3 Then, scores of unmarried women began to leave their family homes to live on their own. By 2010, one in three women between the ages of 20 and 35 had their own household. Many of them undertook what came to be known as “white marriage” (ezdevaj-e sefid), that is, moving in with their partners without formally marrying. These seemingly mundane desires and demands, however, were deemed to redefine the status of women under the Islamic Republic. Each step forward would establish a trench for a further advance against the patriarchy. The effect could snowball.

While many women, including my mother, wore the hijab voluntarily, for others it represented a coercive moralizing that had to be subverted. Those women began to push back their headscarves, allowing some of their hair to show in public. Over the years, headscarves gradually inched back further and further until finally they fell to the shoulders. Officials felt, time and again, paralyzed by this steady spread of bad-hijabi among millions of women who had to endure daily humiliation and punishment. With the initial jail penalty between ten days and two months, showing inches of hair had ignited decades of daily street battles between defiant women and multiple morality enforcers such as Sarallah(wrath of Allah), Amre beh Ma’ruf va Nahye az Monker(command good and forbid wrong), and Edareh Amaken(management of public places). According to a police report during the crackdown on bad-hijabis in 2013, some 3.6 million women were stopped and humiliated in the streets and issued formal citations. Of these, 180,000 were detained. But despite such treatment, women did not relent and eventually demanded an end to the mandatory hijab. Thus, over the years and through daily struggles, women established new norms in private and public life and taught them to their children, who have taken the mantle of their elders to push the struggle forward. The hardliners now want to halt that forward march.

This is the story of women’s “non-movement”—the collective and connective actions of non-collective actors who pursue not a politics of protest but of redress, through direct actions. Its aim is not a deliberate defiance of authorities but to establish alternative norms and life-making practices—practices that are necessary for a desired and dignified life but are denied to women. It is a slow but steady process of incremental claim-making that ultimately challenges the patriarchal-political authority.4 And now, that very “non-movement,” impelled by the murder of one of its own, Mahsa Amini, has given rise to an extraordinary political upheaval in which woman and her dignity, indeed human dignity, has become a rallying point.

Reclaiming Life

Today, the uprising is no longer limited to the mandatory hijab and women’s rights. It has grown to include wider concerns and constituencies—young people, students and teachers, middle-class families and workers, residents of some rural and poor communities, and those religious and ethnic minorities (Kurds, Arabs, Azeris, and Baluchis) who, like women, feel like second-class citizens and seem to identify with “Woman, Life, Freedom.” For these diverse constituencies, Mahsa Amini and her death embody the suffering that they have endured in their own lives—in their stolen youth, suppressed joy, and constant insecurity; in their poverty, debt, and drought; in their loss of land and livelihoods.

The thousands of tweets describing why people are protesting point time and again to the longing for a humble normal life denied to them by a regime of clerical and military patriarchs. For these dissenters, the regime appears like a colonial entity—with its alien thinking, feeling, and ruling—that has little to do with the lives and worldviews of the majority. This alien entity, they feel, has usurped the country and its resources, and continues to subjugate its people and their mode of living. “Woman, Life, Freedom” is a movement of liberation from this internal colonization. It is a movement to reclaim life. Its language is secular, wholly devoid of religion. Its peculiarity lies in its feminist facet.

But the feminism of the movement is not antagonistic to men. Rather, it embraces the subaltern, humiliated, and suffering men. Nor is this feminism reducible to the control of one’s body and the forced hijab—many traditional veiled women also identify with “Woman, Life, Freedom.” The feminism of the movement, rather, is antisystem; it challenges the systemic control of everyday life and the women at its core. It is precisely this antisystemic feminism that promises to liberate not only women but also the oppressed men—the marginalized, the minorities, and those who are demeaned and emasculatedby their failure to provide for their families due to economic misfortune. “Woman, Life, Freedom,” then, signifies a paradigm shift in Iranian subjectivity—recognition that the liberation of women may also bring the liberation of all other oppressed, excluded, and dejected people. This makes “Woman, Life, Freedom” an extraordinary movement.

Movement or Moment

Extraordinary yes, but is this a movement or a passing moment? Postrevolution Iran has witnessed numerous waves of nationwide protests. But this current episode seems fundamentally different. The Green revolt of 2009 was a powerful prodemocracy drive for an accountable government. It was largely a movement of the urban middle class and other discontented citizens. Almost a decade later, in the protests of 2017, tens of thousands of Iranian workers, students, farmers, middle-class poor, creditors, and women took to the streets in more than 85 cities for ten days before the government’s crackdown halted the rebellion.5 Some observers at the time considered the events a prelude to revolution. They were not. For although connected and concurrent, the protests were mostly concerned with sectoral claims—delayed wages for workers, drought for farmers, lost savings for creditors, and jobs for the young. As such, theirs was not a collective action of a united movement but connective actions of parallel concerns—a simultaneity of disparate protest actions that only the new information technologies could facilitate.A larger uprising in December 2019, which was triggered by a 200 percent rise in the price of gasoline, did see a measure of collective action, as different protesting groups—in particular the urban poor and the middle-class poor as well as the educated unemployed and underemployed—displayed a good degree of unity. Their central grievances concerned not only cost-of-living issues but also the absence of any prospects for the future. The protesters came largely from the marginalized areas of the cities and the provinces and followed radical tactics such as setting banks and government offices on fire and chanting antiregime slogans.

The current uprising has gone substantially further in message, size, and make-up. It has taken on a qualitatively different character and dynamics. This uprising has brought together the urban middle class, the middle-class poor, slum dwellers, and different ethnicities, including Kurds, Fars, Lors, Azeri Turks, and Baluchis—all under the banner of “Woman, Life, Freedom.” A collective claim has been created—one that has united diverse social groups to not only feel and share it, but also to act on it. With the emergence of the “people,” a super-collective in which differences of class, gender, ethnicity, and religion temporarily disappear in favor of a greater good, the uprising has assumed a revolutionary character. The abolition of the morality police and the mandatory hijab will no longer suffice. For the first time, a nationwide protest movement has called for a regime change and structural socioeconomic transformation.

Does all this mean that Iran is on the verge of another revolution? At this point in time, Iran is far from a “revolutionary situation,” meaning a condition of “dual power,” where an organized revolutionary force backed by millions would come to confront a crumbling government and divided security forces. What we are witnessing today, however, is the rise of a revolutionary movement—with its own protest repertoires, language, and identity—that may open Iranian society to a “revolutionary course.”

In the first three months after Mahsa Amini’s death, two-million Iranians from all walks of life staged some 1,200 protest actions that spilled over 160 cities and small towns. Friday prayer sermons in the poor province of Sistan and Baluchistan, as well as funerals and burials for victims of the regime’s crackdown in Kurdistan, have brought the most diverse crowds into the streets. University and high-school students have staged sit-ins, defied the mandatory hijab and sex segregation, and performed other courageous acts of resistance, while lawyers, professors, teachers, doctors, artists, and athletes expressed public support and sometimes joined the dissent.6 In cities and small towns, political graffiti decorated building walls before being repainted by municipality agents. The evening chants from balconies and rooftops in the residential neighborhoods continued to reverberate in the dark sky of the cities.

Security forces were frustrated by a mode of protest that combined street showdowns and guerrilla tactics—the sudden and simultaneous outbreak of multiple evening demonstrations in different urban quarters able to disappear, regroup, and reappear again. The fearlessness of these street rebels, many of them young women, overwhelmed the authorities. A revealing video of a security agent showed his astonishment about backstreet young protesters who “are no longer afraid of us” and the neighbors who “attack us with a barrage of rocks, chairs, benches, flowerpots,” or anything heavy from their windows or balconies.7

The disproportionate presence of the young—women and men, university and high school students—in the streets of the uprising has led some to interpret it as the revolt of Generation Z against a regime that is woefully out of touch. But this view overlooks the dissidence of older generations, the parents and families that have raised, if not politicized, these children and mostly share their sentiments. A leaked government survey from November 2022 found that 84 percent of Iranians expressed a positive view of the uprising.8 If the regime allowed peaceful public protests, we would likely see more older people on the streets. But it has not. The extraordinary presence of youth in the street protests has largely to do with the “youth affordances”—that is, energy, agility, education, dreams of a better future, and relative freedom from family responsibilities—which make the young more inclined to street politics and radical activism. But these extraordinary young people cannot cause a political breakthrough on their own. The breakthrough comes only when ordinary people—parents, children, workers, shopkeepers, professionals, and the like—join in to bring the spectacular protests into the social mainstream.

Although some workers have joined the protests through demonstrations and labor strikes, a widespread labor showdown has yet to materialize. This may not be easy, because the neoliberal restructuring of the 2000s has fragmented the working class, undermined workers’ job security (including in the oil sector), and diminished much of their collective power. In their place, teachers have emerged as a potentially powerful dissenting force with a good degree of organization and protest experience. On 14 February 2023, twenty civil and professional associations, led by the teachers’ syndicate, issued a joint “charter of minimum demands” that included the release of all political prisoners, free speech and assembly, abolition of the death penalty, and “complete gender equality.”9 Shopkeepers and bazaar merchants have also joined the opposition. In fact, they surprised the authorities when at least 70 percent of them, according to a leaked official report, went on strike in Tehran and 21 provinces on 15 November 2022 to mark the 2019 uprising.10 Not surprisingly, security forces have increasingly been threatening to shut down their businesses.

The Regime’s Response

The regime is acutely aware and apprehensive of the power of the social mainstream. It has made every effort to prevent mass congregations on the scale of Cairo’s Tahrir Square during the Arab Spring when protesters could see, feel, and show the rulers the enormity of their social power. Protesters in the Arab Spring fully utilized existing cultural resources, such as religious rituals and funeral processions, to sustain mass protests. Most critical were the Friday prayers, with their fixed times and places, from which the largest rallies and demonstrations originated. But Friday prayer is not part of the current culture of Iran’s Shia Muslims (unlike the Sunni Baluchies). Most Iranian Muslims rarely even pray at noon, whether on Fridays or any day. In Iran, the Friday prayer sermons are the invented ritual of the Islamist regime and thus the theater of the regime’s power. Consequently, protesters would have to turn to other cultural and religious spaces such as funerals and mourning ceremonies or the Shia rituals of Moharram and Ramadan.

But the clerical regime would not hesitate to prohibit even the most revered cultural and religious traditions if it deemed them a threat to the “system.” During the Green revolt of 2009, the ruling hardliners banned funerals and prevented families from holding mourning ceremonies for their loved ones. On occasion, authorities even prohibited Shia rituals. This is not surprising. Ayatollah Khomeini, the Islamic Republic’s founding father, had already decreed that the supreme faqih held “absolute authority” to disregard any precept or law, including the constitution or religious obligations such as daily prayers “in the interest of the state.”11 Iran’s clerical rulers would not hesitate to prohibit these cultural and religious rituals, precisely because of their exclusive claim on them. Under this perverse authority, the regime would delegitimize and discard values and practices from which it derives its own legitimacy. For it views itself as the sole legitimate body able to determine what is sacred and what is sin, what is authentic, what is fake, what is right, and what is wrong.

For the regime agents,mass demonstrations of spectacular scale would sound the call of revolution. They do not wish to hear it but cannot help feeling it. For a hum and whisper of revolution is already in the air. It can be heard and felt in homes, at private gatherings, and in the streets; in the rich body of art, literature, poetry, and music borne of the uprising; and in the media and intellectual debates about the meaning of the current moment, organization and strategy, the question of violence, and the way forward.12 The regime has responded with denial, ridicule, anger, appeasement, and widespread violence.

The daily Keyhan, close to the office of the supreme leader, has charged the protesters with wanting to establish “forced de-veiling” and warned that the “Islamic revolution will not go away. . . . So, be angry and die of your fury.”13 The commanders of the key security forces—the military, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, the Basij militia, and the police—issued a joint statement on 5 October 2022 declaring their loyalty to the supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. And the hardline parliament passed an emergency bill on 9 October 2022 “adjusting” the salaries of civil servants, including 700,000 pensioners who in late 2017 had turned out in force during a wave of protests. Newly employed teachers were to receive more secure contracts, sugarcane workers their unpaid wages, and poor families a 50 percent increase in the basic-needs subsidy. Meanwhile, the speaker of the parliament, Mohammad Bagher Qalibaf, confirmed that he was prepared to implement “any reform and change for public interest,” including “change in the system of governance” if the protesters abandoned demands for “regime change.”14

Appeasing the population with “salary adjustments” and fiscal measures has gone hand-in-hand with a brutal repression of the protesters. This includes beating, killing, mass detention, torture, execution, drone surveillance, and marking the businesses and homes of dissenters. The regime’s clampdown has reportedly left 525 dead, including 71 minors, 1,100 on trial, and some 30,000 detained. The security forces and Basij militia have lost 68 members in the unrest.15 The regime blames “hooligans” for causing disorder, the internet for misleading the youth, and the Western governments for plotting to topple the government.

A Revolutionary Course

The regime’s suppression and the protesters’ pauseare likely to diminish the protests. But this does not mean the end of the movement. It means the end of a cycle of protest before a trigger ignites a new one. We have seen these cycles at least since 2017. What is distinct about this time is that it has set Iranian society on a “revolutionary course,” meaning that a large part of society continues to think, imagine, talk, and act in terms of a different future. Here, people’s judgment about public matters is often shaped by a lingering echo of “revolution” and a brewing belief that “they [the regime] will go.” So, any trouble or crisis—for instance, a water shortage—is considered a failure of the regime, and any show of discontent—say, over delayed wages—a revolutionary act. In such a mindset, the status quo is temporary and change only a matter of time. Consequently, intermittent periods of calm and contention could continue to possibly evolve into a revolutionary situation. We have witnessed such a revolutionary course before—in Poland, for instance, after martial law was declared and the Solidarity movement outlawed in 1982 until the military regime agreed to negotiate a transition to a new order in 1988. More recently, Sudan experienced a similar course after the dictator Omar al-Bashir declared a state of emergency and dissolved the national and regional governments in February 2019 until the military signed an agreement on the transition to civilian democratic rule with the opposition Forces of Freedom and Change after seven months.

Only radical political reform and meaningful improvement in people’s lives can disrupt a revolutionary course. For instance, holding a referendum about the form of government, changing the constitution to be more inclusive, or implementing serious social programs can dissuade people from seeking regime change. Otherwise, one should expect either a state of perpetual crisis and ungovernability or a possible move toward a revolutionary situation. But a revolutionary situation is unlikely until the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement grows into a credible alternative, a practical substitute, to the incumbent regime. A credible alternative means no less than a leadership organization and a strategic vision capable of garnering popular confidence. It means a collective force, a tangible entity, that is able to embody a coalition of diverse dissenting groups and constituencies and to articulate what kind of future it wants.

There are, of course, local leaders and ad hoc collectives that communicate ideas and coordinate actions in the neighborhoods, workplaces, and universities. Thanks to their horizontal, networked, and fluid character, their operations are less prone to police repression than a conventional movement organization would be. This kind of decentralized networked activism is also more versatile, allows for multiple voices and ideas, and can use digital media to mobilize larger crowds in less time. But networked movements can also suffer from weaker commitment, unruly decisionmaking, and tenuous structure and sustainability. For instance, who will address a wrongdoing, such as violence, committed in the name of the movement? As a result, movements tend to deploy a hybrid structure by linking the decentralized and fluid activism to a central body. The “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement has yet to take up this consideration.

Civil society and imprisoned activists who currently enjoy wide recognition and respect for their extraordinary commitment and political intelligence may eventually form a kind of moral-intellectual leadership. But that too needs to be part of a broader national leadership organization. For a leadership organization—in the vein of Polish Solidarity, South Africa’s ANC, or Sudan’s Forces of Freedom and Change—is not just about articulating a strategic vision and coordinating actions. It also signals responsibility, representation, popular trust, and tactical unity.

This is perhaps the most challenging task ahead for “Woman, Life, Freedom,” but remains acutely indispensable. Because, first, a political breakthrough is unlikely without a broad-based organized opposition. Second, a negotiated transition to a new political order is impossible in the absence of a leadership organization. Who is the incumbent supposed to negotiate with if there is no representation from the opposition? And third, if political collapse occurs and there is no credible organized alternative to an incumbent regime, other organized, entrenched, and opportunistic forces—for example, the military, political parties, sectarian groups, or religious organizations—will move in to shape the course and outcome of a transition. Such forces could claim to represent the opposition and make unwanted deals or might simply fill the power vacuum when authority collapses. Hannah Arendt was correct in observing that the collapse of authority and power becomes a revolution “only when there are people willing and capable of picking up the power, of moving into and penetrating, so to speak, the power vacuum.”16 In other words, if the revolutionary movement is unwilling or unable to pick up the power, others will. This, in fact, is the story of most of the Arab Spring uprisings—Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, and Yemen, for instance. In these experiences, the protagonists, those who had initiated and carried the uprisings forward, remained mostly marginal to the process of critical decisionmaking while the free-riders, counterrevolutionaries, and custodians of the status quo moved to the center.17

No one knows where exactly the uprising in Iran will lead. Thus far, the ruling circle remains united even though signs of doubt and discord have appeared within the lower ranks.18 The traditional leaders and grand ayatollahs have mostly stayed silent. But reformist groups have increasingly been voicing their dissent, urging the rulers to undertake serious reforms to restore calm. None of them say that they want a regime change, but they seem to see themselves mediating a transition should such a time arrive. Former president Mohammad Khatami has admitted that the reformist path which he championed has reached a dead end, yet finds the remedy for the current crisis in amending and enforcing the constitution. But a growing number of reformist figures, led by former prime minister Mir Hossein Mousavi, are calling for a referendum and a new constitution. The hardline rulers, however, remain defiant and show no sign of revisiting their policies let alone undertaking serious reforms. Resting on the support of their “people on the stage,” they aim to hold on to power through pacification, control, and coercion.19

NOTES

1. Azam Khatam, “Street Politics and Hijab in the ‘Women, Life, Freedom’ Movement,” Naqd-e Eqtesad-e Siyasi, 12 November 2022, in Persian.

2. Danny Postel, “Iran’s Role in the Shifting Political Landscape of the Middle East,” New Politics, 7 July 2021, https://newpol.org/the-other-regional-counter-revolution-irans-role-in-the-shifting-political-landscape-of-the-middle-east/.

3. A woman’s letter to Zanan, no. 35 (June 1988), 26.

4. For a detailed discussion of “non-movements,” see Asef Bayat, Life as Politics: How Ordinary People Change the Middle East (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013). For an elaboration of how “non-movements” may merge into larger movements and revolutions, see Asef Bayat, Revolutionary Life: The Everyday of the Arab Spring(Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2021).

5. Asef Bayat, “The Fire That Fueled the Iran Protests,” Atlantic, 27 January 2018, www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/01/iran-protest-mashaad-green-class-labor-economy/551690.

6. Miriam Berger, “Students in Iran Are Risking Everything to Rise Up Against the Government,” Washington Post, 5 January 2023; Deepa Parent and Anna Kelly, “Iranian Schoolgirl ‘Beaten to Death’ for Refusing to Sing Pro-Regime Anthem,” Guardian, 18 October 2022; Celine Alkhaldi and Adam Pourahmadi, “Iranian Teachers Call for Nationwide Strike in Protest over Deaths and Detention of Students,” CNN, 21 October 2022.

7. Video clip circulated on social media of the speech of a security agent, Syed Pouyan Hosseinpour, at the 31 October 2022 funeral ceremony of a Basij member killed during the protests.

8. According to a leaked confidential bulletin of Fars News Agency and a government survey, reported on the Radio Farda website, 30 November 2022, www.radiofarda.com/a/black-reward-files/32155427.html.

9. Radio Farda, 15 February 2023; www.radiofarda.com/a/the-minimum-demands-of-independent-organizations-in-iran-were-announced/32272456.html

10. Reported in a leaked audio of a security official, Qasem Ghoreishi, speaking to a group of journalists from the Pars News Agency, close to the Revolutionary Guards. Reported also on the Khabar Nameh Gooyawebsite on 29 December 2022.

11. Asghar Schirazi, The Constitution of Iran: Politics and the State in the Islamic Republic (London: I.B. Tauris, 1998).

12. For a discussion on poetry, see www.radiozamaneh.com/742605/.

13. Keyhan, editorial, 6 October 2022.

14. Khabarbaan, 23 October 2022, https://36300290.khabarban.com/.

15. Iranian Organization of Human Rights, Hrana, www.hra-news.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Mahsa-Amini-82-Days-Protest-HRA.pdf; https://twitter.com/hra_news/status/1617296099148025857/photo/1. The number of 30,000 detainees is based on a leaked official document reported in Rouydad 24, 28 January, www.rouydad24.ir/fa/news/330219/%D9%87%D8%B2%DB%8C%D9%86%D9%87-%D9%87%D8%B1-%D8%B2%D9%86%D8%AF%D8%A7%D9%86%DB%8C-%D8%AF%D8%B1-%D8%A7%DB%8C%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%86-%DA%86%D9%82%D8%AF%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D8%B3%D8%AA.

16. Hannah Arendt, “The Lecture: Thoughts on Poverty, Misery and the Great Revolutions of History,” New England Review,June 2017, 12, available athttps://lithub.com/never-before-published-hannah-arendt-on-what-freedom-and-revolution-really-mean/.

17. This predicament resulted partly from the “refo-lutionary” character of the Arab Spring. “Refo-lution” refers to the revolutionary movements that emerge to compel the incumbent regimes to reform themselves on behalf of revolution, without picking up the power or intervening effectively in shaping the outcome. See Asef Bayat, Revolution without Revolutionaries: Making Sense of the Arab Spring (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I understand most of yall hate tiktok but i need you to understand that with twitter on the verge of death, people literally finding themselves unable to download archives of their content, that tiktok is serving a vital purpose right now

If you search names like Shervin Hajipour, Zhina Amini (Mahsa Amini), Hossein Ronaghi, Khodanour Lajaei, or Nika Shakarami on google, you might only find results from September or October. As I'm typing this, November 2022 is almost over.

This particular wave of the ongoing genocide has been ramping up for MONTHS now and you have to dig for updates.

Look back a little further and you'll learn about Bloody November, in 2019. 1500+ peaceful people. Look back further! This battle against genocide isn't new, isn't small, isn't irrelevant. But mainstream news would have you believe it. Meanwhile on TT and IG you can search these tags and find updates as recent as a few hours.

Hashtags on tiktok are allowing people to communicate directly. The internet and ELECTRICITY are cut off in Mahabad and people are being attacked in cities across Iran

yet humans across continents have formed a delicate chain of communication with voice recorders, videos, instagram, twitter, tiktok... this echo is how we hear their cries for help. their literal cries for help. The literal voice recordings of Iranian children and adults in terror being shot at being executed having their homes burned are still making it out of a cities under attack across continents and oceans.

Tiktok is full of vile evil shit just like the rest of the internet. Just like Twitter. but we need these forms of communication.

I am telling you. The content of these videos, which you can find yourself on tiktok or other social media with hashtags like #MahsaAmini, #StopExecutionsInIran, #WomenLifeFreedom, #Mahabad and more, is not being archived for history lessons for your grandkids to watch on a projector. It isn't gonna be broadcast next week on tv news. It is actively being scrubbed, minute by minute, by people who do not want you to believe or care this is happening. People who know that in the age of information excess, out of sight is out of mind. People who know they can enrage more people with Taylor Swift concert tickets.

I download as many videos, as much footage as I can come across. Then I'm moving them to my computer. Then a flash drive. I'm trying to get a library card to access a printer so I can have physical copies of articles. English, Arabic, anything that is direct footage, any summaries of events, I am including the date and location. This is something you can do too. This is something tiktok makes easy to do.

Nobody is telling me to do it but I believe it's going to matter.

I'm 27. I understand the education system. In my time since graduation I've come to understand how much we WEREN'T taught, how much we were taught that was a straight up lie.

Filtering through data is a good skill to have whether you're reading a textbook or using social media.

I'm not telling you to like tiktok or even try it, I'm just saying that if you care about this information then you can find it there, and you can connect with other people who also care.

(Also, there are TON of Indigenous creators using tiktok to share their history, language, art, and updates about issues like threats to the Indian Child Welfare Act. You can't control the algorithm but you kinda can. There are a lot of great people on these apps and I don't want to lose them and I don't want them to lose their space either.)

Archiving, connecting, listening, and learning may not be profitable or encouraged but it is important and accessible work and if you are often housebound or even bedbound, it can be a fulfilling way to reach out to others.

These people in Iran are in danger. They are children, students, people who care about the planet, about equality, about fairness. Thats WHY theyre being executed. These are the people who believe in the future we want and how can we build that future if they're gone? More importantly than their value to future generations, these people deserve to live their own lives, to breathe, to not be afraid.

Many of the recordings I find on tiktok are the first and last bits of connection we have with the people who make them, because they have since been executed or gone missing.

I have seen the photos Kian Pirfalak, a little boy shot to death, his body under ice so it wouldn't be stolen away. People across the ocean knew he died before his father- also injured, still in critical condition from when we last heard- knew he lost a son. His mother attacked while mourning at his funeral.

Ive seen the photos of the devices they use to hang people. People my age. Do you know what I mean? When I watch a video I know it could be removed in an hour. Accounts get deleted and how do you ever find that Person again? that individual, specific person? To help them?

There are people on the internet trying to convince you that 15,000+ humans are not currently at risk of execution. Theyve had a lot of success desensitizing everyone to mass death what with the pandemic and all. Please don't let them. If you cant conceptualize these numbers, just think about one person. Think about the ones who died and why. Think about the ones who are alive and what they need.

I will be posting some of the videos I find on here as well. This is happening in real time and it's being erased in real time. All of this could be gone tomorrow. I don't know what else to say.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

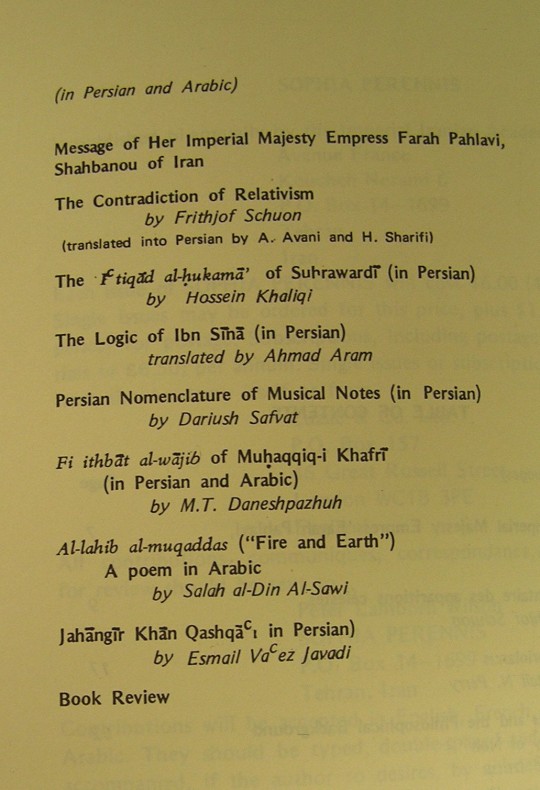

"Hoist with His Own Petard": a Tragic Irony of Seyyed Nasr's Life

In 1974 Seyyed Hossein Nasr, a 41 years old scholar and thinker, a descendant of the Prophet, and a representative of the highest echelon of Iranian intellectual elite, established the Imperial Iranian Academy of Philosophy in Tehran:

(انجمن شاهنشاهی فلسفه ایران).

In the first issue of the academy’s journal “جاویدان خرد”, (literally “Eternal Wisdom” or relying on context “Sophia Perennis”) he announced that the goal of the Academy is the revival of the traditional intellectual life of Islamic Persia.

Indeed, in highly westernized intellectual climate during Pahlavi’s regime where even the Western name فلسفه (philosophy) instead of Persian Arabic حكمة (wisdom) was offered for Academy, Nasr’s academic interests in Islamic philosophy and Islamic Science was very timely. When he was appointed to Tehran University at the Faculty of Letters and Humanities (دانشكده ادبيات و علوم انساني) it was completely dominated by western understanding of humanities.