#and it would make sense for the belief aspect of the 'martyr' definition

Text

365 Days of Writing Prompts: Day 224

Adjective: Daring

Noun: Martyr

Definitions for those who need/want them:

Daring: (of a person or action) adventurous or audaciously bold; boldly unconventional

Martyr: a person who is killed because of their religious or other beliefs; a person who displays or exaggerates their discomfort or distress in order to obtain sympathy or admiration; a constant sufferer from (an ailment)

#i was already going to be late with this prompt because i got home at nearly 2 from hanging out with my close friends#but then i accidentally fell asleep before i could even type this up#so oopsies there#as for the prompt i like it because it feels contradictory while making complete sense at the same time#most 'martyr's in media are shown as releuctant or even fully against them being 'martyr'ed#however if a 'martyr' were to be complicit or involved in their 'martyr'dom that would be 'daring'#and it would make sense for the belief aspect of the 'martyr' definition#because those actions could come from a set of held beliefs that are fringe#i hope all of that makes sense cos its clicking in my brain but i feel like im just saying a bunch of words that lack meaning#thanks for reading#writing#writer#creative writing#writing prompt#writeblr#trying to be a writeblr at least

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

i'm not christian so i apologize if this is a gross overgeneralization but it's weird how Certain Types of christians seem to exclusively prefer to depict and refer to jesus as a baby or a dying/dead martyr... almost like Alive Adult Jesus might have some opinions that don't gel with their lifestyles lmao

You are definitely not alone in observing this, anon! In fact it’s a perennial discussion both among academic theologians and in the pastoral community.

If you’re into Christian history, there are definitely periodic trends in terms of which aspect(s) of Jesus are most emphasized, and they are unsurprisingly very much related to the social and cultural context of the people “doing theology.”

So for example, I’m personally most familiar with early/classical and early medieval Christian history. The earliest Christology was focused primarily on the resurrection (with Jesus’ death seen as an important step on the road to resurrection, but the emphasis always being on resurrection, not the death in and of itself), and the language used by the early church was explicitly the language of liberation. Salvation meant freedom from sin and death, and crucially, sin included what we might now call “social sin”: that is, the sin of inequality in this life. The first Christians preached resurrection, and as a direct result of that, they also preached communal living and a welfare system that would see every member of the Body of Christ taken care of.

They certainly didn’t get everything right. St. Paul encouraged Christian slave owners to free their Christian slaves and consider them siblings, but he never actually called for an end to the institution of slavery or acknowledged it as inherently evil. But we have historical records of Christian communities where the common social divisions of classical Rome were more or less completely broken down, where slaves and free, men and women, people of different cultural and class backgrounds all interacted as equals. In fact, the oldest versions of Christian baptismal creeds we have (which can be found as quoted bits of poetry in a couple of Paul’s letters) make explicit reference to egalitarianism as the greatest hallmark of Christian life.

And that was what worried the Romans. If you grow up in almost any Christian tradition, you’ll hear stories of the martyrs. Christians love our martyrdom stories, you’re absolutely right about that, anon. But all too often we miss the actual reason for the early martyrs’ deaths. They weren’t killed for being “followers of Christ” in the kind of generic, near-meaningless sense of “belief” that so many American Christians often consider to be “following Christ.” The Roman imperial authority, as a rule, did not particularly care who its subjects worshiped, so long as they paid their taxes, didn’t rebel against Rome, and didn’t rock the social boat. The majority of early Christian martyrs were killed for things like refusing to sacrifice to the emperor (which was seen as a symbolic act of rebellion against Rome, as making sacrifices to the emperor was a pledge of political loyalty), refusing to serve in the Roman military, rejecting the authority of Roman governors, upsetting the social order (with all that egalitarianism), and, in the case of the vast majority of women martyrs, refusing to get married (which is another form of upsetting the social order, and a particularly dangerous one because it represented a statement of female independence, both socially and financially).

In the early church there was a heavy emphasis on the the death and resurrection of Jesus, but that doesn’t actually mean that his life was overlooked. It would be truer to say that, for those early martyrs, his life and teachings were intimately tied up with his death and resurrection.

Because here’s the thing that we American Christians, in particular, often either gloss over or entirely forget: Jesus, too, was killed by the Romans. He lived as a second class non-citizen in an occupied country, and he was killed by the occupying authority because he was seen as a threat to that occupation. That’s a historical fact that gets covered over for a variety of reasons, not least the fact that the gospels themselves actively attempt to disguise it. (Why? Because the gospels were written by and for people who were still living under that occupying authority, and who were therefore concerned to make it clear that they were not, in fact, an existential threat to Roman power and did not need to be eliminated.)

And, of course, once Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire, it was also in a position to benefit from the privilege of imperial power.

Jesus’ life - and his death - were profoundly anti-imperial. That’s...a really awkward fact for a religion that has become the backbone of empire to reckon with. So the emphasis of Christology changed. The emphasis now was on Christ as heavenly king, conqueror, ruler of a kingdom of God which looked, for all intents and purposes, exactly like a heavenly version of the Roman Empire.

And American Christians are very much in the position of those imperial Roman Christians. America is an empire. We have vast wealth and resources, much of which we’ve obtained through war and colonial exploitation. We are literally a country built on the backs of slaves, and we used the Christian scriptures to justify that slavery. We use it to justify slavery still. We have a thousand metaphorical explanations for what Jesus may have meant by “sell all you have and give it to the poor, then come and follow me,” because we are terrified of taking him literally. We are profoundly concerned with policing sexuality and gender because that early message of Christian egalitarianism, where there is in Christ no slave or free, no male or female, but all are one is every bit as threatening to the American social order as it was to the Roman order two thousand years ago. We don’t like to talk about Jesus’ cry for justice, about his eager anticipation of the toppling of empire, because we are that empire.

But that’s conservative white American theology. The liberation theology of Latin American, the post-colonial theology of Africa, the womanist theology and the poor people’s campaign arising out of the African American experience of Christianity - it’s no accident that these theologies are far more focused on the life and teachings of Jesus. Because any attentive reading of the gospels cannot fail to notice that, more than any other topic - practically to the exclusion of any other topic - Jesus is profoundly concerned with the liberation of the poor and oppressed.

3K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey, i've seen people talking about what if Varian died because of the mindtrapped brotherhood, but, what if he died during cassandras revenge? He was thrown around a lot, and his ribs were at a risk of being broken. (Which could've potentially impaled his lungs and killed him. Also its more angsty, and cassandra would have to process the fact that she just killed Varian with her own hands. (Also, what if the brotherhood found out. Adira, Hector, Edmund, and Adira would be pissed.) + Eugene.

I've def seen this concept explored before! Or at least many fans treating his injuries from that episode more seriously.

But I feel like w/ AUs or what-ifs where Var dies, there tends to be a lot of focus on just the angst/suffering aspect, which is honestly too bleak for me. And unsatisfying if that's the long and short of it?

So I'd be more interested in this question in relation to the aftermath and how other characters would be affected by the Varian-shaped hole in their lives.

Varian dying before figuring out the Demanitus scroll would actually change a lot and really throw off the plot, b/c Ziti's plan to free herself would be set back without him to translate the second sun incantation for Raps. That’d be a whole diff thing to consider... but if he DID give them the incantation, and didn't make it due to injuries, things would prob proceed much as in canon. Just more somber.

Unintentionally killing someone would really be an event horizon for Cass; it could make her realize this isn't what she wants, leading her to relinquish the moonstone early, or maybe fleeing Corona, and wanting to atone. Alternatively, she could double down on the path she's on and become completely unreachable, b/c this kid dying really confirms her fear that she’s gone too far to turn back- but no matter how she processed and responded to it, I think she'd struggle with deep regret and be pretty horrified. (B/c there IS a big diff btwn Cass killing someone in cold blood and her accidentally fatally injuring them b/c she doesn't know her own strength. Of the cast, besides his dad she might be MOST affected.)

The other characters' reactions are interesting to consider.

Smth that I don't see touched on as much is that in an AU where Varian- the youngest of the group- dies, Raps and Eugene would probably also have a lot of guilt to work through in addition to their grief. They did directly involve him, or allow him to be involved. They'd blame themselves too.

I think Varian would be seen as a hero or martyr, with lots of posthumous honors for his sacrifice. Post-series I can see them naming a library or academy/scientific institute after him, and maybe Raps/Eugene remembering him by naming one of their children after him

Quirin losing his only son to the same force that claimed his homeland and much of his life would be deeply tragic, and I don’t know if his spirit could ever truly recover.

The Brotherhood obviously should've been involved in canon, but smth like this happening in an AU would validate/confirm their fears and beliefs abt the danger of the moonstone and definitely lead to them joining the fight. And yeah they'd be angry? But I think there'd be more sadness than anything.

(Privately, I think Hector might believe this outcome should've been expected, even if it's a tragedy... but I think even he would have the sensitivity and awareness to not to say that.)

Me being me, my take is that grief would bring them together and Hector + Adira would step in to support Quirin in their own ways. The other Old Coronans could rally and manage his farm while he mourned, too.

And then in AUs where something in his life goes seriously awry, I tend to see Quirin traveling back to the DK post-series instead of staying in Corona, b/c it'd be less painful and he'd have an increased sense of purpose there.

Tl;dr I feel like an AU like this would actually be less about Var angst, b/c it isn’t really ABOUT him- he’s just a catalyst, and the real area of interest is his friends and family dealing with loss.

#next pitch for an AU: Hector hits the ground in RatGT and straight up dies#the end#F in the chat#also TY ANON for sending fandom-related asks here#so much easier to answer#anyway re. injuries in TTS#I tend to prefer a middle ground where they're given more gravity#but noone dies or gets maimed for life y'know?#cw character death#angst#ask#text post#my post

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

For the oc ask #4 past, #4 present, #3 future, please. Thanks.

Coming at me again with some really interesting questions thank you talpup 😎😎😎

Past #4 What was the most common argument between them and whoever raised them?

Aika used to have general child-parent arguments but nothing too serious, except when she was 10.

When she turned ten, her parents finally decided to to tell her that she was adopted. She was incredibly upset about it. Then, her mother gave her a choice to do a ritual that would make her their daughter. It was of course a forbidden ritual but Aika didn’t know at the time but her dads did. They didn’t want her mom to do the ritual while Aika was adamant about it. She desperately wanted to be a part of her family.

Eventually she won the argument, but her dads were upset at her mom for even enabling this situation in the first place. She did the ritual and overtime, she started looking more and more like her mom.

Another major argument was about dating astkgdkyvuho she saw this noble boy visit her village when she was 12 and developed a massive crush on him. She just thought he had the most adorable smile, beautiful eyes and hair she would just want to run her hands through.

But ofc her parents said no. Even her brother was like 🤨 and she was upset about it for weeks but it certainly made her idealize him even more and it even shaped her type afshdhdufkggk

Present #4 Do they have any enemy factions or groups? Why and how are they opposed, and how do they feel about it?

Well, there were some unnamed groups of people and sometimes, even countries, that sought after Aika for her Time Magic because it was OP asf but as I’ll explain in the next chapter, Arthur comes along and changes the memories of nearly everyone to forget she even had Time Magic in the first place. But these countries were already preparing to go to war and stuff and for their memories to make sense and match with reality, they had to go to war with other countries for serious or superficial reasons.

That is the price of asking Arthur for a favor. He didn’t do it on purpose because in the end, he is the one who has to mediate peace as the head of the Pascere Syndicate, but that was the only way the their new memories would make sense.

Aika hated that era of her life and carries a world of guilt from it because many of her friends died fighting in the subsequent wars while she was stuck being pregnant for nine months. Right now, though, her life is way better and she has enemies for different reasons.

Future #3 How would their beliefs or morals change in the future, if at all?

Aika is about to turn 36 in the fic soon. She is a grown woman who wouldn’t have changed as much if Julius hadn’t come along.

Before she even met Julius, she had just gotten better at dealing with her depression and anger issues but not much. She still has bouts of anger and ruthlessness, has self-confidence issues(which she hides very well) and doesn’t smile as much. In fact, people who had known her for years would find it strange if they see her smiling(well, everyone except Arthur). But Julius comes along and makes her smile as if everyday was Christmas. He’s such a positive influence in her and she even tries to model some aspects of her behavior after Julius.

Another thing about Aika is that she would never sacrifice her life for anyone. Not even her own daughter. She only surrounds herself with people who believes are capable and strong. She raised her daughter with high standards and ensured that she was strong. Holly had to grow up quickly because of it and she doesn’t complain now(but definitely will in the future). She wouldn’t put her life on the line but she would definitely save anyone from a tough situation. She just refuses to be a martyr and sacrifice her life.

Aika understands why anyone else would sacrifice their own lives for their loved ones or their kingdom and is perfectly content with Julius if he did want to die for his kingdom(cough). But that doesn’t mean that when the time comes, she wouldn’t be there to save him(well not exactly but I can’t say further than that bc then it would be spoilers 😏) but because of him, she learns that sacrifice is actually really satisfying and fulfilling and because of him, she learns to be a better mother.

#long post#oc: aika tolliver#julius novachrono#julius & aika#bc oc#black clover oc#oc ask game#thx for whispering 🥰#talpup💕

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Well, since we are already talking about knights, what about a knight of hope?

Oh hello!! That’s my Classpect, right there!! Fancy that. I’m sayin this partly 8ecause I think my Role is pretty damn cool and partly as a wwarnin up front that yeah, there’s 8ound to 8e a 8it of 8ias in this here analysis. I wwill say that I’m fairly proud of my original analysis a this Role, so I’ll be drawwin on that fairly heavvily for this one. Anyhoww, wwithout further ado, here’s the…

Title: Knight of Hope

Title Breakdown: [Expert Catalyst] of [Epistemic Culmination]

Class: Knight. Generally considered to be either a “defender” or a “wielder”, the Knight is a sort of jack-of-all-trades Class characterized by both insecurity and tremendous force of will. Knights arm themselves with their Aspect and use it as a barrier between themselves and the world, as they attempt to take on as many tasks as possible in order to address, ameliorate, or compensate for that which is diminished or absent in the makeup of their Session. The Knight’s complement/opposite is the Rogue [the Expert Carrier], and it is analogous to the Thief [the Expert Commander] and the Page [the Expert Counselor]. They are most likely to work well with Maids [Catalytic Engineers] and Mages [Esoteric Catalysts].

Aspect: Hope. An Aspect associated with the conflict between one’s most salient conscious desires - personal, psycho-sexual, socio-political, or whatever else - and one’s better angels, so to speak - in simpler terms, the conflict between the ego and the superego - Hope represents the sum of one’s beliefs and ideals. It’s for this reason that Hope is tied to religious imagery and especially to angelic imagery. Additionally, Hope is associated with the double-edged sword of idealization - of people (both individuals and sorts of people) and of goals or aspirations towards heroism, adulation, happiness, moral rectitude, and success or victory. Finally, Hope can be interpreted as encompassing such things as one knows without evidence - epistemic leaps of faith. Hope stands opposed to, and represents a complement to, Rage [Epistemic Incipience], and is analogous to Light [Epistemic Communication] and Void [Epistemic Integration]. It manifests most intensely in concert with Time [Ontological Culmination] and Doom [Ethical-Aesthetic Culmination].

Mechanical Profile: Hope is the most powerful Aspect (and yes, I’m going to remind you all of that at every opportunity). However, it’s also the hardest Aspect to “control” (or at least, it’s tied with Rage on that count), so all those Hope-bound are, well, bound to have their work cut out for them in terms of developing their Aspect-linked faculties. Knights, to, have their work cut out for them, both due to the stumbling-block of the...distinctive...mechanisms by which they cope with their insecurities, and due to the tendency of their Class towards jack-of-all-trades-ism. The Knight of Hope will best serve their session by finding all those places whereat Hope is lacking, and allowing what little Hope there remains to become most efficacious. This can be differentiated from the manner in which, say, a Sylph, would ameliorate a dearth of their Aspect by creating more of it - the Knight does not, and cannot, create or repair Hope. The Hope they find must, alas, remain as fragile or broken as it stands - the Knights power and responsibility lies in allowing the faint Hope - dangling, as it may be, by a string - to effect as much change as possible, despite its diminution or fragility.

In terms of Magic Powers, the Knight of Hope does have a bit of an edge, for despite Knights’ lack of outstanding aptitude with the more abstract-ergo-magical facets of their Aspects, Hope as an Aspect conceptually encompasses all things magical, by which I mean all things predicated on belief. This is the Class that has a sword and shield so long as - and only so long as - they believe themselves to have a sword and a shield. There’s an element of literal “plot armor” here - Hope’s link to constructed or idealized narratives (the Game Master’s proverbial railroad) channelled through the Knight’s lens of “protecting the self/loved ones/the session itself”. This Role could prove instrumental to a Session’s success, provided the player assigned it doesn’t succumb to certain unfortunate tendencies - the martyr/messiah complex, the escapist’s propensity for to seek oblivion by way of substances and other such worldly vices, and of course, the Hope player’s resolute urgency which all-too-often metamorphoses into cocksure arrogance (which arrogance, then, becomes that much more of a liability in concert with the sort of dependence and insecurity to which Knights are given.)

Before I diverge too much further into such content as belongs in the next section, I’ll close this one with a brief comment on the Knight’s path to Ascension, and the powers such Ascension might confer. The Knight of Hope has a fairly clear path to Ascension - the question is whether the Knight has the willpower to walk it. To Ascend, one must first die, and while our Knight of Hope would surely be the first to profess their willingness to die for the good of their fellows/the advancement of their cause/the pursuit of perfection (take your pick), the follow-through’s the rub here - recall the moment at which Dave, a player cast unto a rather similar Mythological Role, is first met with the opportunity to Ascend. I’d speculate that the average Knight of Hope would be...similarly hesitant. Should they follow through, however, the unification of the dream-self with the waking self would enhance the Knight’s powers tremendously, given the fact that the unification of the ideal and the real is, essentially, the foremost goal and function of a Knight of Hope (at least within the context of the Game). Hope’s power is limited only by a given Hope-bound player’s own mental limitations - what they are and aren’t willing to believe. The Ascended Knight of Hope would be nigh invulnerable, and armed with the ability to veritably elevate their own Hume Level (that is to say, bend the definition of the Game’s “reality”, to a degree proportional to the difference between their Hume Level and that of their environment), so long as their confidence and self-control hold out. The first shouldn’t be a problem. The second is….another matter entirely. Which brings us to...

Personality: So, Hope players and Knights are both big-time projectors. To clarify, Knights (like Thieves and Pages, their analogues) are largely defined by their aspirations; all four Expert Classes are characterized by starting out with a dearth of identity outside of the identities of their actual or fictional idealized role models. Likewise, Hope players (like Light and Void players - notice a pattern?) have a tendency to externalize their sense of identity, tethering the image they present to the world to people or ideas outside of themselves. Just as Light players tether themselves to actualities (real individuals, information perceived as objectively true, or concrete objects) and Void players tether themselves to abstractions (social constructs or perceived obligations), Hope players tether themselves to ideals - concepts, images, or qualities seen as supreme, quintessential, or otherwise larger-than-life (for example, Jake’s idealized vision of Dirk, or Eridan’s invented - and strikingly meta - interpretation of his role as Prince of Hope). All of this is to say that the Knight of Hope is likely to protect their ego by concealing the characteristics about which they’re insecure behind idealized “perfect” versions of those characteristics - if they see their faith as weak, they will project sanctimony and “saintliness”; if they see their confidence as faltering, they will present as a primadonna; if they see themselves as inconstant, lazy, or given to prevarication, they will do their damnedest to be seen as The Determinator.

As a final note, the Knight of Hope is an Active Hope player (yes, we’re still doing the Active Knight deal here), so they’re almost certain to be optimistic to a fault. Even if they try to mask it in some attempt to preserve an image of reason, “cool”, or humility, they’ll be resolute in their conviction that they’re on the right track, and may be quietly dismissive of any assertion to the contrary. Their personal development is predicated on that thing to which Knights are nigh-universally averse - introspection and differentiation between the Actual and the Ideal. Read the Serenity Prayer once or twice, friend. You can’t make everything perfect all the time, and you and those around you alike will be that much better off for your taking that on board.

~

8oy, that one wwas fun. I might’vve gotten uhhhhhhhh 8it carried awway - hope ye don’t mind. And as a final note, I’ll remind those readin that this is my Role, and so it’s 8ound to 8e evver-so-slightly tinted 8y my ego. Caveat emptor an so on an so forth ::::p

Oh, an one more thing!! I’vve done this one 8efore, like I said in the introduction. So here’s Past Sasha’s take, if you’d like to check that out. It says some things wwith wwhich I still agree, 8ut couldn’t fit in here.

~ P L U R ~

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey there! I just found you and honestly your readings are soooo coool, may I have one about my future love life too? Will I meet someone and how will they be? Possible star sign? AND ALSO PLEASE THIS IS IMPORTANT : when i first made the sorting hat Test I was a Ravenclaw but after a couple years it started changing to gryffndor and then back to ravenclaw and I’m having the biggest identity crisis.. can you help me on this? What house am I? Hope this is not to much..if it is just ignore me haha

Oh also i don’t know if you need this but I’m 23 male and a libra! Btw I don’t see a sign that reading are open on your blog and got a bit ahead of myself so if they’re closed right now I’m very sorry, I mean no offense! Thank you anyways and have a great day! :)

Oh, I just do these for fun.

That said, your house is not an identity nor is it any sort of useful personality trait; once you're not at school any longer it's 100% irrelevant.

Star signs are also not a personality trait nor are they relevant to any aspect of your life (that's just something people use to try and excuse poor behaviour on their part; you didn't do the thing because you're a Gemini or a Scorpio or an Ares or any other sign, you did it because you were being inconsiderate and not thinking your actions or words through; you're not incompatible with someone because of their sign either, you're incompatible with them due to basic personality conflicts or conflicting wants/needs out of a relationship), they're just little tidbits of facts and have no actual influence or impact on anything.

If you're referring to 'quizzes' that tell you what house you ought to be in, I'd invite you to read up on confirmation bias. That applies to thinking you're a certain way because of your star sign; confirmation bias will give you that truth because you want it to be the truth,

Those are designed to be easily manipulated to give the answers the person taking them wants based on their mood at the time; I can guarantee you I could take any one and get a different result based on my mood at the time of taking them.

Do not base any part of your identity around a house at a school or your zodiac sign, it doesn't make you somehow more interesting or desirable; if anything, it's a red flag that indicates you aren't willing or capable of taking responsibility for your own actions or reactions.

Anyone who tells you otherwise is probably getting paid to tell you otherwise.

Remember: If you're paying them, they'll want to keep you as a repeat customer and will likely tell you what they know you want to hear.

In this case, what you want to hear is that you'll meet your soulmate soon and that you're definitely Ravenclaw.

I doubt the latter given your belief that it matters in the slightest and, as I'm not getting paid, I couldn't possibly care less whether or not you'll meet someone, what they'll be like, or their star sign (which is, of course, completely irrelevant).

Just to give an example, from what you said in these I already know several things about you and, were you paying me, would be able to easily tailor a reading to play into exactly what you want to hear.

Things that were made clear by information you voluntarily offered:

- You're a bit on the insecure side.

- You're a bit immature, which is indicated clearly by you being well beyond school age and borderline obsessing over your house.

- You're single, obviously.

- And you don't want to be.

Cards weren't necessary to give me that information, you offered it up freely, and when you're paying someone, they will absolutely tell you what you want to hear to keep you coming back as a customer.

Be extremely wary of people who make you pay to do tarot/rune/other readings; they take seconds to do and, with the information provided the customer, are extremely low effort.

At least, they are for me.

Similarly, be wary of anyone who wants you to pay for them to perform a spell or ritual for you; it likely won't do anything at all beyond a placebo effect as the rituals/spells they offer are things that you need to do yourself if you want them to benefit you and not the one casting them.

That, and if you're trying to put something negative out there, most will know how to rework it so any negative consequences they might get hit with for doing that sort of thing hit you and not them.

At any rate, the way this deck often prattles on, it spends the first few cards confirming who we're talking about, and that's what it's done here.

I was right in that little list.

You're insecure, likely have abandonment issues due to past relationships (romantic, platonic, familial, or otherwise), have a hard time trusting people, have a tendency to be overly dramatic which can and will drive people away eventually, if you have had relationships in the past you're either not over them or are still damaged from how they ended and haven't taken steps to heal and move on, and that, where relationships are concerned while you can be exciting and spontaneous, you can also be incredibly fickle and very likely aren't at a place in terms of mental health or maturity to handle a commitment.

This is where it starts to bridge out into what you asked and it starts, where the Fool left off in the paragraph above, by indicating that, for the time being, all you're likely to find are what amounts to whirlwind romances that don't last all that long.

The Nine of Wands backs that up in terms of future romance, and also goes back to mentioning that you need to deal with all of those issues above before anyone is going to be able to put up with you long term.

Six of Cups typically revolves around immaturity and occasionally an ex or someone you had wanted to have a relationship with coming back into your life.

Three of Cups backs up that, "Someone from your past returning" or a dry spell, as it were, ending.

You'll need to start working on your issues if you want anything to last, however.

Hm.

The deck doesn't seem to want to move on, it's repeating itself in the sense of, "Fix your issues, even the ones you're in denial about or don't want to face." That includes fear of rejection (that would be the Two of Swords in this case).

While the Two of Cups does indicate you'll meet someone with whom you have a strong connection and mutual attraction, cards in a reading are not islands; the cards around them matter, and all of the previous cards to this one were very, very clear in that you need to get yourself together, likely via professional means, before even the most attracted to you person is going to be able to tolerate the level of insecurity, drama, and baggage you'll also bring to the table.

This isn't, "you need to love yourself" nonsense, it's, "you need to deal with your mental health, your tendency to be overly dramatic where no drama is necessary, and self esteem issues so you're on relatively stable ground."

The Ace of Wands following the Two of Cups is a fairly blunt statement to forget any fear of rejection and let the other person know you're interested. If you sit around waiting for someone to just turn up for you, you're probably going to be waiting for a very long time as reality just doesn't work that way very often.

And it's finally moved on to the second bit you were asking about: What that person will be like.

Unfortunately for you, the old proverb "in cauda venenum" applies to this person. They'll initially come off as generous, completely devoted, doting, giving you everything you could possibly want. They'll give you all the support, stability, and positive influence you could ever ask for.

...and then they'll either get bored or get tired of having to play the part of your partner and therapist (see everything above) and leave. The Five of Swords also has heavy connotations around abuse so it's equally possible that they were never the kind, loving person they let you think they were until they knew they had their claws firmly into you and, once they know you're too wrapped around their finger to ever leave, they'll start with slow, subtle abuse, gaslighting, making you feel like they're the only one who will ever love you, etc...of course, to the public, they'll be a loving, kind martyr who puts up with what they'll tell others is YOUR poor behaviour because they love you that much, all of which can eventually lead to physical abuse, especially if they get the feeling that you're going to try and leave.

Whichever it is, the Five of Swords in terms of relationships is never a good thing.

The star sign of this person is irrelevant, but one typically sees behaviour like that in people who take star signs far too seriously and are also Gemini, Scorpio, literally any fire sign, and Libra.

All in all, you need to work on yourself before you start jumping into relationships in any serious capacity. If you're not already getting professional mental health help that includes therapy, start as soon as possible.

As for the House thing, again, it's entirely irrelevant, you're 23, you've not been school age for some time now. Absolutely and literally nobody cares what your house is past the time you left school. It has no bearing on identity.

Ordinarily, I'd be able to tell you that based on the deck's description of you but there is no house that has an encompassing trait of, "complete mess", so I'll see if it'll give me a little more clarity.

...and it's given me a muddled mess of repeating itself but under the pervasive traits that keep getting repeated throughout the last--however many cards I've drawn now--a recurring theme, though usually in the negative sense of holding on to things that should have been long since let go and moved on from, is loyalty to those you choose to be loyal to even when it becomes self-destructive, and hard work, primarily to avoid having to let go. Keep in mind that any positive trait can easily turn dark, as it were, when misapplied or taken to the level of obsession.

That would indicate Hufflepuff but, let's see if I can get the deck to stop twisting the knife as we've already been over enough of that.

Devoted, compassionate, caring, generous, with the Wheel and Two of Pentacles indicating that this isn't the answer you wanted, which I also could have told you because you seemed hellbent on hearing Ravenclaw or Gryffindor.

While the Page of Swords has some brief flashes of Ravenclaw traits (inquisitive, curious, etc...) as before, cards do not stand on their own in a reading and nearly everyone has those fairly generic traits.

It moves on going back to more traits that point toward Hufflepuff: Down to earth, sensible in general, a nurturing/caretaker type, loyalty, being able to easily make people feel welcome.

The Queen of Swords backs that up in both traits along the lines of being empathetic, welcoming, fair, and, when representing a person, an air sign.

Libra, as I'm sure you know, is an air sign.

Sounds like Hufflepuff to me.

#tarot#divination#long post#hufflepuff#definitely hufflepuff#this deck rambles about as much as I do

1 note

·

View note

Note

I have a question about byg. From what I understand it's not byg if you have several other characters of the same orientation but I want to make sure my specific situation is okay because the death is kind of connected to her sexuality. Basically one of my lesbian characters sacrifices herself for my MC (who is also a lesbian) because she loves and believes in her. There are 5 other lesbians in the story (including the MC). Is this still byg b/c of the circumstance?

As a general rule, the mod team don’t have universal stances on what constitutes BYG. Personally, I am of the belief that in every situation that an LGBT+ character dies within the story, it is BYG (unless they die of old age). But some folks think something can only be called a trope if it has other unethical aspects attached to it. The amount of lesbians in a story doesn’t absolve this particular issue. If you have one lesbian villain and other lesbian rep that isn’t villainous, then that might balance it out and make it okay. But a dead lesbian is not balanced out by another one being alive. It might lessen the blow but it doesn’t necessarily absolve it exactly. Proportionately, the only thing that would make sense (to me) is if you are killing your straight characters in the same or more population proportions as your lesbian characters. If 1 out of 5, or 20% of your straight characters also sacrifice themselves, that would maybe lessen the blow. Resurrecting your character would also make it better. Pretty much, if your character must die, it’s about harm reduction. Figure out the impact it will have on audience members who relate to that character. Who may already be at risk for thinking their lives are only valuable in death.

But your dying character being part of a relationship dynamic also makes it not okay. This reply by @sensicalabsurdities to this post covered this idea perfectly:

sensicalabsurdities said: i would say another thing as far as quantity goes is to also think of gay relationships as single units. If you have two gay male characters who are uninvolved and one of them dies, you have a ‘we’re not killing all the rep’ situation, but if those two are dating and it’s your only gay mlm relationship, suddenly you’re in the ‘gay relationships never end non-tragically’ area

I would say that what you are describing is a BYG situation, especially because it is connected to her love life. It is generally the case that LGBT+ characters are automatically put into self-sacrificial roles and die for entertainment value. (Think: those queens from The Dragon Prince season 2. I think someone told my Buffy had something like that too? But I haven’t seen that part of the series yet.)

So I would refrain. It’s also really toxic to martyr LGBT+ characters, whose lives are already far too often deemed disposable. Making a decision to sacrifice yourself is not something you want to encourage in your LGBT+ readers. We are already treated like burdens and broken and problems as people.

tl;dr this is definitely Bury Your Gays, in my opinion, and I strongly advise against this.

- mod nat

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Doubling Down’ Rant.

I feel like one of the most prominent aspects of this episode was the portrayal of the characters’ psychology, the writing and the dialogue did a great job portraying how people spiral into toxic relationships on the first place, and why it is difficult for them to get away once they've fallen in.

Kyle for one, is portrayed as a caring and moral-ridden individual that although reasonable, lets his emotions get in the way of his course of action. Kyle wanted to intervene because he considered it to be the right thing to do, never once entertaining the idea of an ulterior motive with Heidi until the other girls proposed it to him. While all the other boys aknowledged Cartman’s poor treatment of Heidi, none of them were willing to get themselves involved.

This takes us to Kyle's initiative and how his and Cartman's dynamic plays out throghout the episode. Kyle has consistently been responsible for challenging Cartman’s attitude, positioning himself as ‘good’ and Cartman as 'evil’, this relationship that has ultimately served to feed both Cartman’s enthusiasm to torture him, and Kyle’s sense of selfrighteousness and tendency to see himself as a martyr, victimization is something Kyle has in common with Cartman, but to quote, 'We all wrongly see ourselves as the victim sometimes, but Cartman sees himself as the victim ALL the time’. Kyle differentiates himself in being able to aknowledge his mistakes and learn from them.

To get some insight into Kyle’s remark: 'In a way, I feel like we’re all going out with Cartman right now’ reflecting on how all of them are, at some degree, and specially Kyle, always been involved in a toxic relationship with Cartman’s mind games. Kyle has been, for a long time now, Cartman’s main sympathizer, he can’t help but look out for his personal improvement, often attempting to get him to do the right thing and aknowledge the fault in his ways, a cause that Cartman hasn't hesitated to take advantage of, tricking Kyle into commiting to a mean if he can profit from his support.

In this episode, Kyle appears to have come to the conclussion that Cartman is beyond help, and that neither he nor Heidi can do anything to change that, for the best thing they can do for him is not to feed his sociopathic needs, furthermore demonstrated by their encounter on the hallway, with Kyle continuously trying to reason with him and assure him it was all for his own good, Cartman making deaf ears to his claims, finally leaving Kyle no choice but to knock him out in self defense, who apologizes regretful.

Cartman, on the other side, is miserable with Heidi, but also without her. As I stated on my last post concerning their relationship:

'He can’t bring himself to end the relationship and thus giving Heidi freedom of choice, she’s his property and so Cartman can’t stand the idea of his belongings moving onto other people. Cartman thinks of Heidi as a tool that exists with the only purpose of being at his disposition to give him attention and validation on command, no more and no less.

Simultaneously, Cartman can’t stand Heidi, because she doesn’t Cartman’s idealized image of her. Naturally, Heidi isn’t the tool Cartman expects her to be, she is an human being with her own individual needs. Whereas Cartman seeks a relationship where he is prioritized over all, never giving anything in return, and a partner willing to follow him blindly against all the odds, without him having to worry about losing their support; Heidi looks for a functional, healthy romantic relationship, were all the parties involved contribute their part. Cartman is unwilling to fulfill this role, because doing so would position him as an equal of Heidi’s, which means, to him, degrade him from his high-entity status.’

Nearing the end we realize Cartman has found a way of manipulating Heidi into believing she’s in the relationship she's craved for, and thus avoiding any sign of resistance on her behalf. He has learned that if he wants to manipulate Heidi successfully, he needs to put a little effort on the relationship every now and then, offering her occasional reassurance when things seem grim. This way, Cartman can act selfishly while at the same time 'rewarding’ Heidi for her subservience, throwing away any doubt she might've had in him. He fools her into believing his toxic behaviour is a necessary mean that needs to exist in order to keep improving himself.

Heidi is someone who wishes to aid the needy, she cannot bring herself to refuse someone’s cries for help, which is, besides the ironic effects of peer pressure, the main reason she continues to be stuck with Cartman and allows herself to be manipulated by him. He sees in Cartman someone who takes bad decisions, but is fundamentally kindhearted. Someone who is in need for her guidance. Even when ditching Kyle after being gaslighted by Cartman, her kind nature is a definitive trait of her character. Cartman was persuasive enough to make Heidi compromise with his beliefs, he made sure his words appeared to be reasonable. He told her what she wanted to hear when she was feeling the most guilty, deflecting the blame for the failure of their relationship unto Kyle instead, but reassuring her by telling her he hadn’t been counscious of his actions. He convinced her of attributing her own supposed flaws ('being moody’) to her ethnic background, and this way implying she has no control over ever improving herself, comforting her but making her feel helpess over her situation at the same time, this serves to Cartman as a mechanism to increase her emotional dependence to him, by making her feel he’s the only one who will ever love her despite her imperfections.

Regarding Cartman’s idea of Kyle, I feel like Cartman projects all of his own corruption unto Kyle. He subcounsciously thinks of Kyle as his equal, although he cannot recognize the corruption from within. Kyle’s intentions are never pure in Cartman’s mind, he must always be plotting something against him the same way he himself does to him. To him, Kyle’s purpose in life is to get in Cartman’s way. As the series progressed, we’ve seen Cartman gradually watering down his hostility towards Kyle in latter seasons the more time they spent together, and instead replacing it with an odd sense of familiarity and trust, until this point, Cartman’s friendly demeanor towards Kyle that even manifested itself at one point earlier in the episode, takes a sudden turn the moment Cartman finds out he might have been responsible for his breakup with Heidi. Following this event, we see Cartman’s hatred towards Kyle reach its peak when he goes batshit after his trippy jewish dream sequence, spewing all his resentments against Kyle in spite of the latter’s attempts to excuse himself, Cartman feeling betrayed after letting himself 'fall into Kyle’s claws’ by allowing him the benefit of the doubt previously.

Having stated all this, I think Cartman has taken care of the problems he had with Heidi, and now that the challenge is over, the last scene leads me to believe he has shifted his interest from the pleasure he obtains from having domain over her, to the impact his behaviour towards her has on Kyle instead. He’s using his influence on the people around Kyle to make them into proxys as a mean to inflict pain onto him. Heidi is no longer the tool, his entire relationship with her is now a tool on itself.

It was also interesting to see the conection between B plot and A plot relying on the parallel of the toxic relationship between Cartman, Kyle and Heidi, and that of politicians with their supporters, instead of having each storyline intersecting with the other, though I don’t have a strong stand on the matter, since I’m for the most part ignorant concerning the USA political status.

The weakest point of the episode in my opinion was the introduction of elements that seemingly served no purpose in the narrative, and ultimately aimed for a specific purpose in order to lead the plot in a certain direction. For example, Cartman’s dialogue when making fun of Heidi for gaining weight after tricking her into introducing meat into her vegan diet, indicated he had a goal in mind by doing this, though we never get any insight on what this particular goal may be other than to reassure his dominance over her. Besides this being a dangerous move for Cartman to make just after getting Heidi’s trust back, it seemed like it didn’t serve any purpose other than to incite Kyle into intervening in the relationship. Another example would be Cartman visiting Token’s house, there wasn’t really a point for Cartman to do this besides giving him the chance to make racial remarks some more. Finding out about Kyle being responsible for his breakup with Heidi through Token’s dad seemed too coincidental, though I don’t really mind, even less after being presented with Cartman’s fantastic Kyle delirium sequence.

I really enjoyed the execution of the humor, there were some great jokes, the animation team did an amazing job and overall I think this was a fantastic episode with a rather dark thematic.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

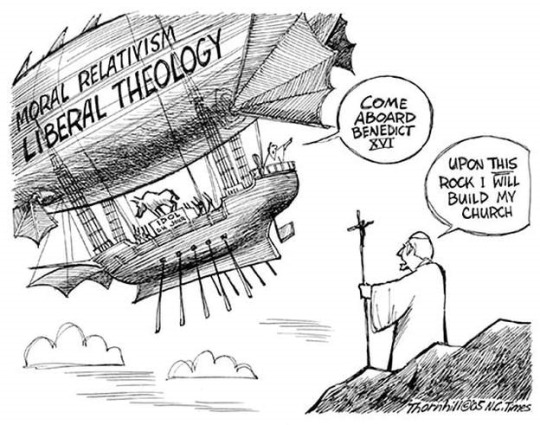

Cultural Atheism: Response To A “None”

By: Anthony Chiozza

Illustration Source: Professor Mark Thornhill granted permission to run his cartoon via email.

Reprint from: 10/16/2017

I Am A Sinner

About two years ago I wrote a commentary on the current social moral order called, “Cultural Atheism and The Death of The West.” This is a response to one of the comments I received. I was not aware that the piece had any comments at all. I apologize for not responding in a timely manner.There is quite a bit to unpack, so I have broken his comment down into sections in which I respond to his question, or statement.

Question: In the spirit of open debate. How are we to know you are not damaged?

Response: I am damaged. I am the worst sinner I know. We are all damaged to varying degrees because of the fallen state of man. Whether you accept the pretense of the fall in the Garden of Eden, or not, if one cannot recognize that one's self is inclined towards things that are not good for the self, or others necessarily, then that person will lead a very hard life. I am inclined to stay in a state of Grace as much as possible. I frequent confession as much as I can.

Question: In your closing you stated “These poor souls, addicted, brain damaged, and increasingly programming themselves to continue in the downward spiral are truly not fit by their own evolutionary faith.” Where have you been given the moral authority to make this assessment?

Response: I am also a poor soul, and in much need of prayers. I am glad you brought this point up because something is in grave need of clarification. I am in no way judging any individual on their internal moral standing with God. I am observing the general actions of society, the rejection of the Church and her Bride Jesus Christ. This results in a judgement based on those external actions compared to God’s Law. Specifically, that moral authority comes from Jesus, when He gave that same authority to Peter with the Keys to Heaven, and to the other apostles as well in the form of forgiving, or retaining sins. The Church, which has been granted the same authority Jesus had, expects me to preach the Truth of Love through actions. I must use the talents God gave me to point to the Truth. I would be a coward otherwise.

Faith and Reason

Further, I am grateful for your courage to ask the difficult questions. I am well aware that this answer may not suffice to someone that does not believe in dogma. I myself believe that the Logos made Himself Truly manifest as the second person of the Holy Trinity, Jesus Christ. He did this because He does, in fact, love us. My Faith is based not on pure blindness, but also on reason. The Church believes in the use of both Faith and reason. Either one standing alone is a grave error. Thus, my authority to speak on the morality of the West comes from Faith and reason. Part of my reasoning is based on well respected scholars in academia which have confirmed that documents such Ignatius of Antioch’s letters, Polycarp’s letters, and Just Martyrs works are in fact legitimate historical documents. This is further evidence to support the historical Jesus than evidence for someone like Alexander the Great, and other well known historical figures. We also have the writings of the historian Josephus on Jesus and the fall of the Jewish Temple in 70 AD.

I am well aware that even with the historical evidence, I am still accepting on Faith that Jesus is in fact who He said He was. The Logos. The Son of God in the flesh.

A Thought Experiment

Another example of my reasoning is based on the actions of early Catholics. One can reason that Early Christians, the first apostles included, were willing to suffer and die for a belief which essentially outlines eternal joy. However, this religion also made heavy demands on the early Catholics to carry their cross. Catholics can not give into certain illegitimate pleasures. This task of keeping oneself pure, confessing, being humble, and in many cases being butchered as a martyr seems very unreasonable, unless the miracles that converted the pagans were real. Let’s conduct a thought experiment. Let us suppose I walk into a rowdy bar one evening where all kinds of drinking, drug use, and impure behavior is taking place. I stand up on the table, and I yell that everyone should knock it off right now, or they will go to hell. In absence of a miracle to prove my point, I would be thrown out of the bar, and probably beaten for good measure by people that are of an equivalent mindset of the very pagans that were converted in Rome. A good Priest I know gave just this example.

Falsifiable Scientific Confirmation & Conversion

A final and more definitive example of why it is reasonable to believe is because of the Eucharistic miracle in Lanciano, Italy. Then over one thousand years later the example of the Eucharistic miracle in Poland. The Eucharist, otherwise known as what appears to be bread and wine after Consecration, is in fact really the body and blood of Jesus Christ made truly present for us to become one with Him.This is taken on Faith, but God knows that the weakness of our own state of being will prevent us from seeing this Truth. Doubting Thomas needed to put his fingers into Christ's wounds before he would believe. Jesus has done no less for us modern men. Thus, the scientific study conducted by highly skeptical, atheist scientists identified that both sets of DNA from these two separate events were exact matches. This lead to at least one scientist's decision to leave atheism behind and become Catholic. I am aware for most people this is still not enough evidence, through reason, to explain where I get my authority to make such a general judgement on Western society, but I would simply ask them a question in return. Where do you get your authority to make judgments on the moral standing of other individuals' actions, and your own? If one is honest with the self, that is a difficult question to answer.

The Founding Fathers Are Not Impeccable

Question: I am a Pagan I believe in our country’s preamble to life liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Where is it written that to pursue pleasure is a satanic act?

Response: I don’t personally grant any sense of infallibility, and impeccability to the Founding Fathers of the United States. Although some of Christendom's principles were retained regarding some laws when the founders created the Constitution they failed to recognize all of God's Law and authority. Obviously, you can’t murder even though some find it pleasurable, and pursue that very act for their own pleasure. These sets of moreys go back to the Greeks and elsewhere in various civilizations, but these ideas were certainly vastly improved on by Christendom. I consider this lack of clarification on religion, and morality to be one of the Founding Father’s biggest mistakes, and one that will lead to the downfall of this nation. Other scholars of that time in the University system, protestant and Catholic alike agreed with that opinion.

Error Has No Rights

Question: Are you asserting that life is misery and suffering and that only by understanding that can we be spiritually free?

Response: No. That is another heresy Catholicism had to deal with when converting pagans. Pleasure is something we derive from an act, or thought. That act, or thought has to meet right reason. Right reason consists of following certain moral principles laid out by the Church God gave authority to. If I engage in the marital act with my wife in order to be united with her in Love, and to produce children, that act meets right reason. Even if the act is solely for the unitive purpose, because we know she is not at a time of month where she will bear a child, it still meets right reason. If we choose to avoid pregnancy using NFP because of some dire circumstances, which the Church has explained, we are still using right reason. If I go seek pleasure in another woman, destroy my family, and the hearts of my children, this does not meet right reason. If I eat three pieces of cake a day this does not meet right reason. If I eat one small piece a day, enjoy that pleasure, and do not continue to indulge, it meets right reason. God wants us to have pleasure, but just as science has shown regarding the human brain, the pleasure center over indulged, will lead to serious problems. I am sure you know individuals you might have judged to be selfish. What is it that makes them this way?

Statement: If so I believe you are headed towards the Buddhist school of thought.

Response: Some Buddhism does overlap with the Catholic Faith, but the more correct way of saying it would be that Buddhism is correct in some aspects, and wrong in many others. The most obvious being that you can’t pull yourself up by your own bootstraps spiritually, because this in itself is an act of pride relying on self. You must ask for the help of something outside of yourself. This is precisely why we see certain archetypes in some of the literature I am sure you have read.

Question: Also you state in your article ” This is best demonstrated by simply suggesting that, perhaps, God does exist. Maybe, just maybe, there might be some evidence for that. ” Which would squarely put these people in the camp of agnosticism.

Response: I am not saying they are agnostic. The point is that there is typically an anger response rather than a reasoned response. Perhaps they claim atheism, but quietly are agnostic and this is the reason for that emotional lashing out. I am aware of the difference. The general premise of this article is that, practically speaking, most people behave like someone that would truly manifest atheism brought to its logical conclusion philosophically. That conclusion being, I am my moral authority, and those morals can change on a dime to suit my whim. Thus, we have the idea of moral relativism which is expressed on some spectrum by many individuals within society.

Statement: Agnostics are not moral relativist. They are people who have chosen to believe much like I have that dogma is not the answer. Dogma in itself is what separates the religions. ( I realize that is merely a statement of fact.)

Response: Agnostics certainly are moral relativists. By choosing to believe what you believe to be correct morally, based on your own thoughts, or even the thoughts of other men, is moral relativism from the view of Christ's Church. You may live your life by a certain code of conduct, and even manage not to flip on a dime, but from Christ's lens the rejection of some His Laws is moral relativism. Jung, for example, has some good ideas, but to follow a man that claimed just to be a man as a moral authority seems like a mistake.

The same could be said about my own set of beliefs, given Jesus was not who He said He was. I do believe He is in Fact the Logos made manifest. This is where the very authority comes from that gives me the ability to say, “I am not the one that is the moral relativist.” Further, dogma must exist for the idea of moral relativism to exist outside of a culturally subjective form, because otherwise there is no constant to compare relativistic thought to in its absence. The Faith in the Law we were handed from Moses came from the Trinity. Moses never said this is the Law I created, or this is my Law. He said it was the Law God gave him. Jesus further points out in the New Testament that the Pharisees themselves do not believe that Moses wrote the Old Testament. If they had believed, they would have lead their lives very differently. It can thus be said that the Pharisees were morally relativistic as well. They followed the letter of the Law for their own gain, but not the heart of the Law. I am well aware of the general definition of moral relativism being subjective based on one being a part of a particular culture, but that is clearly not what I am speaking about here. Further, I have listed reasonable criteria to believe the Catholic Church has the authority of God behind it.

Statement: It is my personal belief that Carl Jung was the most correct when he assigned archetypes to the great humanistic experience. This is to understand that God (which I refer to as the universal energy or spirit) Appears different to all individuals egos based on their current residence in the space time continuum. Meaning the more time and experiences you actually have in this universe the greater your difference of opinion about what God truly is will be from your contemporaries. Agnostics that find a belief in a higher power are not satanist. The only reject dogma in a logical search for a personal contact with a living holy spirit which is the creator or architect of the universe.

Response: “Any that reject Jesus Christ and His Church are the first born of satan.” This paraphrase was said by some of the early Church Fathers. That does not necessarily mean that someone engaged in the honest exploration of the Truth is the first born of Satan. For example, we would never say that about Saint Augustine on his journey to grasp at the Truth honestly. Surely he was a sinful man like anyone else, but that reference would never be used because he converted. There are many other cases like his, but someone that knows precisely what the Church teaches, has been a witness to the Truth of Love in its fullness. If they continue to openly reject it, they are in fact in Satan’s camp whether they like to admit it to themselves, or not. I don’t say this out of false charity, but out of Love. I know my assessments are correct for other reasons as well.

Specifically, when I read the Ten Commandments, and works like that of Thomas Aquinas, I know that by following God's Laws I am fulfilling the greatest expression of God’s Love in the world. I see how breaking that Law is for my pleasure, and how that doing the opposite of those Commandments causes someone else pain. The Church and Scripture further break down those Ten Commandments into their nuanced components that are missed by many that claim to be Christian. There are many things that are actually sinful, which are a part of those Ten Commandments, that many people miss without the guidance of the Church.

In short, my pleasure, which does not meet right reason, will cause myself, or another person's pain. Some people may consider it arrogant to tell others how they should consider living their lives. However, if you find yourself on the opposite side of a Christian trying to explain their Faith, and possibly charitably correcting you, of all people, consider two things. One, it is incredibly difficult to actually explain to someone else how they should live their life because you are terrified of the typical reaction you know you are going to receive. You will not win any popularity contests, and find yourself quite friendless. Two, if someone really considers themselves a Christian look at it from Penn’s perspective from comic duo, “Penn and Teller.” Penn says you should be offended if a Christian does not approach you and nicely tell you about their Faith. In light of what they supposedly believe it means they don’t really care about you, and could hardly really be considered a Christian. His exact words were, “How much do you have to hate somebody to not proselytize?”

The fact is I know the Faith I hold to, and the authority it carries, comes with a cross for each individual. Jesus said if we were to follow Him we must pick up our cross. He even said if we love our parents, wives, or children more than Him, which means loving them more than His Law, we are not fit for His Kingdom. You see, if we don’t love His Law first, we can’t really love them because we are not being honest. It is a false love we show, which is simply a going along to get along mentality. Sometimes, the most difficult aspect of following Christ’s Way is charitably correcting our own family, when we know the reaction will not be good no matter how nice we are about it.

Choosing to be Catholic is not easy. It makes serious demands, and it takes a lot of courage to constantly assess your own interior motives. It takes further courage to explain the Truth to others. Christ's authority was rejected as well, and He was crucified. How many souls could someone as sinful as myself possibly convince, if Jesus Himself was put to death by the crowd? I expect nothing less for myself.

I am a fallen human being myself, in need of Communion, and confession, because even though I see this Truth, I still need God’s help to live His Truth. Please pray for me brothers and sisters. God bless.

youtube

#Atheist#None#AtheistNone#Catholic#Bible#bibleverse#biblequotes#holy bible#conservative#republican#democrats#democrat#repuclicans#maga#president#protestant#infowars#alex jones#red pill

0 notes

Note

Hi, I have a crappy memory and can't remember if I asked for a session request (I don't wanna rush you or anything I just can't remember if I sent it before) It was for a Knight of breath, Mage of time, Heir of space, Seer of void, Sylph of heart, Prince of hope, Page of Life and Thief of rage and quadrants if you do them (Especially for the Knight, Mage and Heir) You don't have to,like, answer this right now, I just wanted to know if I sent it, sorry to bother !

It’s been seven days since Mod Nix spoke to a human being. Her hands are dry and her knuckles itch.

Binary checklist: Master aspects: Present. Unrepeated classpects: Present.

Mage of Time: “One who guides themselves through knowledge pertaining to and through timelines, progression, and Time itself.” Along with the Witch and thefully-realized Page, the Mage of Time is definitely one of the bestpossible Time players a session can have. This player knowseverything there is to know about time, timelines, and time travel,and although it begins to infringe on Mind, they likely have a solidgrasp on cycles of causation. Your Mage has an inherent sense ofTime, a perfect internal clock; however, because of the Mage’sCurse, for all their efforts they may be constantly too slow toeffect what they wish to effect, late to all their appointments forreasons not their fault. Hopefully they’re not an easilyfrustrated person. They have about the average capacity forbetrayal, especially if they feel like they’re the ones doing allthe work in the session, with their teammates just lounging about.

Heir of Space: “One who inherits, embodies, and is protected by artwork, creation, and physicality.” The Heir of Space is a natural at the interpretation of fine art, worldbuilding, and the generation of ideas, although they rarely bother to put in the effort necessary to actually produce any finished works of their own. Given their protection by Space, the Genesis Frog should already be accounted for. They might have an unfairly efficient metabolism, given their entitlement, and are almost certainly middle-upper class to unnecessarily rich. Despite their tendency toward athletics, it’s unlikely this player is on any teams, since they’re used to not having to try for their skill. There’s very little chance they’d outright work against the team, although they might get annoyed if they feel unappreciated.

Knight of Breath: “One who exploits to the utmost freedom, pathways, and chaos, and wields it as a weapon.” The Knight of Breath is a revolutionary, they’re a democrat from the Golden Age of Greece, and they flourish when the people are being restricted. In the beginning of their session, when the lack of Breath they bring is most pronounced, the focus is on fighting restrictions (and all the self-sacrifice and determination that comes with it). As a Knight, this player may be a little too engaged with becoming a martyr; again, their activity will be most pronounced in the earlier stages of the session. Although certain facets of Sburban mechanics are made to be easily broken or bent, bu a determined Mage or any Witch, watch out trying to do anything of the sort here without this player to correct you; due to the natural deficit of Breath in your session, arbitrary rules may be immovable without a realized Knight of Breath exploiting what small amount of Breath remains present to return the restrictions to their usual status. I see this player being not overly taken with the team; they’ll be more concerned with their own affairs on their land. They have some propensity for abandonment, but not betrayal.

Sylph of Heart: “One who heals or heals through identity, self-expression, and romantic relationships.” This player is a matchmaker, and has probably written at least two self-help pamphlets. May or may not be the author of Eat, Pray, Love. They’re a romantic, taking refuge in knowing who they are and encouraging others to do the same. Having said that, their intervention isn’t positive per se; while the rest of their team is unrealized, encouraging them to follow their instincts may do more damage than good by pushing the players toward the flawed parts of their personality as well as the satisfactory. On the flip side, upon the realization of all players, identity crises will happen much less often; this player, who’s always defined themselves by their role as a healer, may find themselves apparently isolated. They might get annoyed, but are too focused on helping to really do anything whatsoever against the team, including just leaving home base.

Prince of Hope: “One who destroys or destroys through a flood of faith, belief, and success.” Eridan Ampora. Pick a crusader or televangelist. This is one of the aspects in which the Prince is not necessarily realized before they begin destroying through it, rather than destroying it. Evidence does not stand in their way; they likely pick and choose what to believe based on what feels best to them or relieves the most anxiety, which makes the Sylph of Heart particularly dangerous around them. Hopefully your Thief will temper this somewhat, and if your Page of Life successfully realizes, they can force the Prince onto a more productive track, destroying not through blind faith or personal beliefs but through faith in their peers and chances of success. Among Princes, this is a particularly powerful one that can make or break a session. Before they’re realized, I would suggest they have an absolute chance of betrayal if the Thief isn’t constantly stealing their motivation. Of course, their presence will inflate chances of success greatly -- at least, in the beginning.

Page of Life: “One who creates, encompasses, and fulfills life energy, maturation, and personal growth.” The Page of Life is a fucking savior because, frankly, a Mage of Time, Prince of Hope, and Thief of Rage give me little hope (even with the flood the Prince’s presence produces). Imagine a coefficient given for each player representing their chance of realization. An Heir of Life’s is 1 (100%). The average Page’s might be 0.1. Square that and you’ve got the coefficient for a Page of Life: 0.01. Good chances. They’ll start out, naturally, with a complete deficit of their aspect (the least mature person one could ever suffer). They’re probably also sick half the time, or at least sleep way less than they should, whether that’s their own fault or not. (They certainly don’t do anything productive with that time.) If they do mange to realize, I use no irony when I say they will be able to force the rest of your team to realize immediately, with circumstantially simultaneous epiphanies for the whole ectobiological family and a good ive cases for your Sylph at least. Frankly, although they’ll be uberpowerful post-realization, I can’t see them doing anything against the team beforehand just because they have so little ability.

Thief of Rage: “One who steals and redistributes passion, drive, and emotions to and in order to benefit themselves.” The Thief of Rage is the life of the party, bouncing off the walls, perpetually in the spotlight, and tiring everyone else the fuck out. Living with them before they’ve realized produces a depressive lack of willpower; there’s no point trying to stop them because they always take things too far and have no intention of stopping now. The good news is that, since they’re stealing the motivation of everyone around them, they should realize quickly (assuming they don’t make any horribly rash decisions borne of their personal frenzy beforehand which, admittedly, is a big assumption. Hopefully your Mage will fix their mistakes). At that point, they’ll be much more capable of taking control of their abilities and redirecting them at Dersite enemies, and will probably become the leader of the team, if only because they’re the only one who wants to be. Given their quick (poor) judgment, they probably wouldn’t last long betraying the team, but they don’t want to, anyway.

Seer of Void: “One who guides others through and through knowledge pertaining to secrets, ignorance, and the Furthest Ring.” Though the Thief will lead the session, this Seer is a more localized version of the Chessmaster, executing their plans on a personal basis and using their knowledge of what everyone else doesn’t know to benefit the team. Having said that, they likely have some bias to their thinking on Void; take Albus Dumbledore, a man hated in some parts of the HP fandom for his manipulation. The most obvious potential bias, and the one easiest for this player to fell prey to, is the belief that they’re protecting others by withholding information from them, something that perseveres in the face of mounting opposite evidence. By the time of their completed realization, though, they’ll have thrown it off, more fully understanding the possible negative facets of Void as well as those positive facets they’ve always extolled. They’re also at slightly higher risk of falling under the influence of Horrorterrors, if you believe that gazing long into an abyss leads to the abyss also gazing into you. (Only chance of betrayal is due to grimdarkness.)

Overall: Frog Hunt: Despite the Knight and Mage, your Prince and Heir should be enough to vastly overcompensate. 95%. Black King: With the Mage and Knight as combined strategists and offensive players, the Seer on strategy, the Prince, page, and Thief on offense, and your Sylph healing, you’ve got a good team. (I’m going to assume complete loyalty and team realization here and correct for it in the loyalty section.) The Page is also a great healer. 95%. Loyalty: Up ‘till now I’ve been giving the highest possible chances I’m willing to, but here we run into trouble. Chances are, your Page won’t realize. The Prince will probably go AWOL, and your Thief will be too self-absorbed to really do much for the beginning of the session. 15% you won’t destroy yourself.

Winning: I’d like to give you something high, but that loyalty stat is killing you, plus the presence of a player Time hates. Chances of success with anyone surviving is 60%. Success with everyone surviving is 10% (which is generous in itself).

~{o-o~} Nix {~o-o}~

PS

From Mod Rae: Mage ♦ Heir Mage ♥ Thief Heir ♥ Page Heir ♠ PrinceKnight ♦ Thief Knight ♥ Seer Sylph ♦ Page Prince ♥ Thief Thief ♠ Seer

Remember that these are all possibilities, not inevitabilities.

#session#sessions#mage#time#mage of time#heir#space#heir of space#thief#rage#thief of rage#page#life#page of life#prince#hope#prince of hope#knight#breath#knight of breath#sylph#heart#sylph of heart#seer#void#seer of void#mod nix#nix#quadrant#quadrants

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Political Lives of Dead Bodies