#contractility

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

on god i need to do more plant speculative biology because I always feel like even talented creators fudge the details. Especially when it comes to motile plants and "animals" made of plant-like matter. Like dunmesh put a lot of care into explaining how living armor moves via contractile links in a colony of animals but the dryads were just kinda... hollow like a balloon? What motile mechanism were they using that took up so little space but was powerful enough for them to attack with the same force as a humanoid? and very little of their appearance seemed to be influenced by the growth patterns plants exhibit, they were pretty much perfectly humanoid but with leaf crowns. Not singling out DM here, it's just a case study of something having very good bio but its plant stuff is a mixed bag. DM's mandrakes on the other hand are great, I loved their rooty appearance and the detail of them only being consistently man-shaped because of selective breeding by humanoids

#hydraulic motion in plant-like motile organisms is also so under utilized#perfect excuse to design an alternative to contractile musculature

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

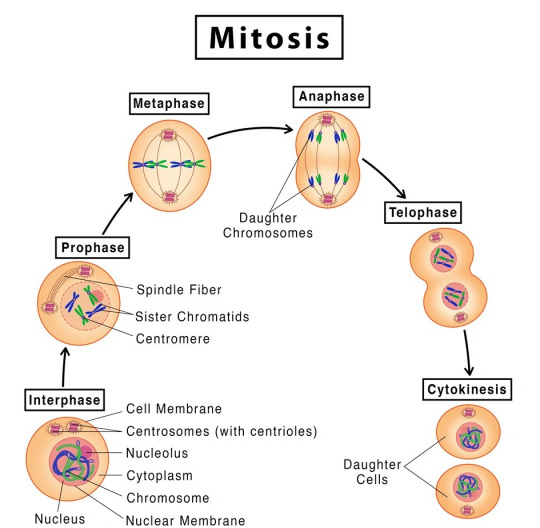

MITOSIS- its Occurrence, Stages and Significance.

Unlocking knowledge one post at a time! Check out our latest notes on www.microscopiaiwm.com – a treasure trove of insights, ideas, and inspiration. Dive in, explore, and let the journey of discovery begin! 📚

INTRODUCTION: Mitosis is a type of cell division that takes place in living organisms and it is commonly defined as the process of duplication of chromosomes in eukaryotic cells and distributed during cell division. The process where a single cell divides resulting in two identical cells, each resulted cell contains the same number of chromosomes and…

View On WordPress

#anaphase#asexual reproduction#cell cycle#cell cycle stages#cell division#cell plate#chromosome#cleavage furrow#contractile ring#cytokinesis#daughter cell#daughter cells#division of cytoplasm#division of nucleus#dna#DNA double#duplication of chromosome#fragmoplast#genetics#germ cells#homologous chromosome#homologous recombination#homologous recombination repair#karyokinesis#kinetochore#kinetoplast#meiosis#metaphase#MicroScopia IWM#mitos

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 2.5 - Ctenophora - Tentaculata

(Sources - 1, 2, 3, 4)

One of two classes of Ctenophora is Tentaculata, the “Tentaculate Comb Jellies.”

The common feature of this class is a pair of long, feathery, contractile tentacles, which can be retracted into specialised ciliated sheaths. Instead of stinging cells, the tentacles have colloblasts, which are sticky-tipped cells that trap small prey. Some species may flick their tentacles to lure prey by behaving like small planktonic worms. Body size and shape vary widely among tentaculatans. Some are bioluminescent, allowing them both to scare away predators and attract small prey: from microscopic larvae and rotifers to the adults of small crustaceans. They are named for the comb rows of cilia which they use to swim. The beating of these combs refract light, producing rainbow-like colors.

Propaganda under the cut:

The Redspot Comb Jelly (Eurhamphaea vexilligera) is unique in that it can actually produce bright orange-yellow ink as a means of escaping predators

The “Warty Comb Jelly” or “Sea Walnut” (Mnemiopsis leidyi) (though I grew up calling them “Leidy’s Comb Jellies”) (image 4) has an oval-shaped and transparent lobed body that glows blue-green when disturbed. It is biologically immortal, can consume ten times its body weight, and its anus only appears when it’s ready to defecate. They are native to western Atlantic coastal waters, but have become established as an invasive species in European and West Asian regions.

Named after the Greek goddess of sailors, the genus Leucothea can be identified by their oblong bodies which have fairly long lobes, taking up almost half of their length. They are transparent, bioluminescent, and have gelatinous spikes that are thought to serve a sensory purpose as they are found to point towards stimuli, the way a ship points towards its destination.

The Venus Girdle (Cestum veneris) (image 3) is the largest ctenophore of all known ctenophores, reaching up to a 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) in total length. Venus girdles resemble transparent ribbons with iridescent edges. Canals run the length of the ribbon in which bioluminescence activates when disturbed.

Haeckelia is a genus of ctenophore which is unique in that, instead of colloblasts, it has cnidocytes, explosive stinging cells usually only present in cnidarians. It does this by stealing and retaining cnidocytes from its cnidarian prey.

Some deep sea tentaculatans are blood red, as this allows them to be camouflaged in the deep sea, where red light does not reach.

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

A bioreactor that mimics a circulatory system can deliver nutrients and oxygen to artificial tissue, enabling the production of over 10 grams of chicken muscle for cultured meat applications. These results are publishing in the Cell Press journal Trends in Biotechnology on April 16. "Our study presents a scalable, top-down strategy for producing whole-cut cultured meat using a perfusable hollow fiber bioreactor," says senior author Shoji Takeuchi of The University of Tokyo. "This system enables cell distribution, alignment, contractility, and improved food-related properties. It offers a practical alternative to vascular-based methods and may impact not only food production but also regenerative medicine, drug testing, and biohybrid robotics."

Read more.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

External Force

In times of old, important people were carried high on litters. Teams of people stood beneath and worked together to heave a structure up. This collective application of force is also what happens, at a somewhat smaller scale, during hair follicle formation. Researchers have been examining the mechanical forces at play as cells move and develop when they form first a placode (a thickening in the skin’s epithelium), and then a follicle. They found that placode development is driven by forces in the surrounding tissue (pictured, with a marker of contractile proteins (top), and cell nuclei and structural keratin (blue and pink, bottom) in mouse skin tissue). The forces were strongest around, rather than within, the placode. How mechanical forces are applied, and the impact they have, is essential to healthy tissue and organ growth, so understanding this interplay could inform future treatments for disorders where tissue structure is disrupted, such as cancer, or for regenerative medicine.

Written by Anthony Lewis

Image from work by Clémentine Villeneuve and colleagues

Stem Cells and Metabolism Research Program, Faculty of Medicine, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

Image contributed by the authors under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence

Published in Nature Cell Biology, February 2024

You can also follow BPoD on Instagram, Twitter, Facebook and Bluesky

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paramecium Caudatum showing nucleus, organelles, contractile vacuole complex, food vacuoles & oral groove

#nature#photography#science#education#adorable#explore#funny#Paramecium Caudatum#protozoa#cell#unicellular#nucleus#organelles#vacuoles#animal cell#gif#gifs#biology#awesome#beautiful#beauty

65 notes

·

View notes

Note

What kind of critical care medications are available to use on a patient? What makes them work?

Thanks for the ask! There's dozens of meds I've seen used in critical care situations, so I will just go through a few of them that I think are most helpful.

Nitroglycerin is used when patients are having a hypertensive crisis. It comes in little pills that they put under their tongue (sublingual administration). The body breaks this down to make nitric oxide. This is the same thing that your body makes when you need to lower your blood pressure. The endothelium of your vessels makes this, and can be signaled to do so by several molecules and transmitters. This vasodilates, lowering blood pressure and allowing tissue to be perfused better.

Albuterol is a bronchodilator that is used to treat asthma and COPD. It is typically inhaled. This is a ß2 agonist that binds to the receptors on the smooth muscle of airways. When it does this, it causes adenyl cyclase to make ATP in cAMP. This does three things. First, it inhibits inflammatory cells. It also causes hyperpolarization of the muscle cells, preventing contraction. Finally, it decreases calcium in the muscle cells and prevents the phosphorylation of myosin (a muscle fiber), both of which inhibit muscle contraction.

Epinephrine is most commonly used to treat anaphylaxis and asthma. It can be injected or inhaled. It acts on adrenergic receptors, and is also a hormone and neurotransmitter made by your body. The effects of it are the same as the effects of the sympathetic nervous system. So it will increase heart rate and contractility, increase respiratory rate, bronchodilate, inhibit insulin, and increase the breakdown of glycogen. On lists of its effects, you'll see that it vasodilates and vasoconstricts, but what it really does is decrease peripheral blood flow by constricting those vessels, and increase the diameter of coronary vessels.

Atropine is an antimuscarinic that is used to treat bradycardia (slow heart rate) and several types of poisoning. It does this by blocking muscarinic receptors, which can be activated by acetylcholine. This will decrease the slowing effect of the parasympathetic nervous system (inhibiting the inhibition and causing sympathetic effects), thereby increasing heart rate. In organophosphate poisonings (pesticide) and soman/sarin gas attacks, it acts the same way. In these poisonings, the enzyme that breaks down ACh (a neurotransmitter) is inhibited, and an accumulation of ACh occurs. Atropine is a competitive antagonist of ACh, meaning it locks into the same receptors but does nothing. It is usually used with another drug (pralidoxime), which can regenerate the enzyme that breaks down ACh. A fun fact about atropine is that it is found in the deadly nightshade (belladonna) plant, and is a poison itself (I mean everything can be a poison in the right amount but this is like a famous one).

Narcan is an opioid receptor antagonist, used for opioid overdoses. It comes as a nasal spray, as this allows it to bypass the blood-brain barrier and be absorbed really quickly. Its mechanism of action is that it blocks opioid receptors but doesn't do anything (conversely, opioids activate those receptors and modulate pain). One fun fact about this one is that someone should not need more than two doses of it. I've seen firefighters give someone three or four doses of Narcan and the person is not waking up. Don't do that. Something else is wrong and you should probably deal with it instead of wasting more Narcan.

If you need anything explained better, just send another ask, DM me, or comment on this post.

I hope I answered your ask well enough, and thanks again :)

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

In a normal esophagus, contraction waves are progressive, and the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxes properly to allow food to pass. However, disorders like achalasia, diffuse esophageal spasm, and hypercontractile esophagus disrupt this process.

In general, all patients with suspected achalasia should initially undergo upper endoscopy and/or esophageal barium swallow; findings may support the diagnosis.

Esophageal manometry is indicated to establish the diagnosis (confirmatory test of choice), irrespective of the initial imaging findings.

Achalasia is marked by the failure of the LES to relax, leading to difficulty swallowing, regurgitation, and weight loss. A key diagnostic feature is the bird-beak sign on a barium swallow, with high LES resting pressure observed on manometry.

Diffuse esophageal spasm presents with retrosternal chest pain and simultaneous, repetitive contractions. Patients often experience dysphagia and pain, particularly during eating. The hallmark finding is corkscrew esophagus on imaging.

Lastly, hypercontractile esophagus, also known as jackhammer esophagus, shows extremely strong contractions and often retrosternal pain. Manometry reveals a high distal contractile integral (DCI), indicating very forceful contractions.

Management includes lifestyle changes, medications like calcium channel blockers or nitrates, and in severe cases, endoscopic therapy or surgery to improve esophageal function and patient quality of life.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hassanain Qambari and Jayden Dickson, rodent optic nerve head showing astrocytes (yellow), contractile proteins (red), and retinal vasculature (green).

2023 Nikon Small World Photomicrography Competition

#hassanain qambari#jayden dickson#researchers#photographer#science#rodent optic nerve#nerve#micro photography#nikon small world photomicrography competition#nature

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

After Hours (Single Story)

In the hushed sanctuary of Carmella’s private clinic, the sterile gleam of polished chrome and the quiet hum of monitors held sway, a world apart from the pulsing heat locked inside Lydia and Bailey’s bare forms.

Naked beneath the clinical glow, they stood poised at the edge of an experiment that stretched limits far beyond science—where every racing heartbeat might become a wave of shattering ecstasy. The air hung thick with the scent of antiseptic mingled with anticipation, an electric tension that whispered promises no protocol could fully contain.

Lydia’s pale, bronzed skin caught the faint clinical light like molten metal, muscles taut with a lithe, practiced grace honed through relentless discipline. Her athletic silhouette was an elegant contrast to Bailey’s more compact strength, the younger woman’s lean, bronzed limbs shimmering with a soft sheen of fine sweat. Bailey’s chest rose and fell with measured breaths, the faint rise of defined abdominal muscles a testament to years of unyielding training beneath the calm surface. Both women bore the unmistakable marks of cardiovascular excellence—hearts mapped in every curve, pulse throbbing visibly at throats and chests alike.

Lydia’s gaze swept over Bailey with the exacting precision of a scientist and the fire of a seductress. Her voice, low and deliberate, brushed the charged air between them. “This next phase will push the boundaries of cardiac and sensory experience, Bailey. My new aphrodisiac targets the heart itself. Each beat will send shivers and waves rippling through your body, magnifying sensation until ecstasy cascades free.”

Bailey swallowed, a flicker of nervous tension betraying her steady exterior. “It sounds… incredible. But also overwhelming,” she admitted softly, fingers flexing as if to grasp the unseen current flowing between them.

Lydia smiled, a knowing, slow curve of lips that hinted at danger and delight in equal measure. “That is why we begin with the dobutamine injection. It will elevate your cardiac output, pushing the heart to deliver with greater force and rhythm before the pill takes effect.”

The younger woman nodded, curiosity overriding hesitation as she reclined onto the cushioned examination table. The pale vinyl stretched taut beneath her athletic frame, the supple contours of her skin glowing warmly against the sterile white. Bailey’s eyes flicked upward, momentarily catching Lydia’s luminous blue, shining with that rare blend of scientific zeal and intimate promise.

From a polished tray, Lydia selected a syringe already prepared with the clear, viscous dobutamine solution. Her hands moved with deliberate confidence—graceful and exact—as she checked the dosage once more, murmuring to Bailey the pharmacologic details, her voice a weave of clinical expertise and seductive calm. “This catecholamine will increase heart rate and contractility. Your cardiovascular system will respond immediately—stronger beats, quicker pulses. It’s the perfect precursor to the aphrodisiac’s wave.”

Bailey’s pulse fluttered visibly at her throat, breaths growing ever so slightly quicker as Lydia’s fingers brushed a pale forearm with reassuring gentleness before sliding beneath her biceps to expose the skin at the crook of her elbow. Lydia’s eyes flicked up, seeking consent, before the needle slid smooth and sure, cool liquid seeping into the network of veins beneath. Bailey’s hand clenched lightly around the table’s edge, an electric tremor rippling through her frame.

Minutes passed with a charged stillness as the dobutamine coursed through Bailey’s bloodstream. The familiar flush of increased blood flow bloomed across her skin, the delicate pink expanding over cheeks, neck, and chest. Her pulse surged, palpable now against the translucent skin of her throat, throbbing in a steady, insistent rhythm that pressed outward like a drumbeat under fine glass. The Erwachte Pumpe’s monitors glowed quietly, broadcasting every nuance of Bailey’s intensified cardiac ballet.

Lydia’s voice softened as she extended the slender white pills between trembling fingers. “Now, we add the aphrodisiac. Three pills—crafted to couple every heartbeat with waves of rising pleasure.”

Together, they swallowed the small capsules, the smooth motion witnessed in soft inhalations and the barely audible clink of swallowing. The room seemed to hold its breath as the compounds began to stir. Bailey’s skin deepened to an almost fiery rose, her heart pulsing hard enough to sketch a visible rhythm beneath pale flesh. Each beat was a tempest in miniature, vibrating through muscle and bone, the relentless call of life itself.

Without hesitation, Lydia withdrew one of the wireless transmitters—the small titanium disc gleaming softly under the clinical lights. Her fingers traced the subtle valleys of Bailey’s chest before settling the device just above the apex of her heart. The cool metal kissed warm skin, an intimate contact laden with unspoken invitation.

Pressing her ear gently to the rise and fall of Bailey’s chest, Lydia inhaled the powerful cadence against her cheek. The heartbeat was a torrent of vitality—a "THUD-DUM, THUD-DUM" thundered like an ancient war drum beneath her skin, each contraction jarring the flesh in time with pounding desire.

With her free hand, Lydia slipped between Bailey’s parted thighs, fingers sliding through the slick folds, seeking the core where muscles curled in eager welcome. Her touch was practiced, precise—exploring the G-spot with exacting rhythm that danced alongside the wild beats surging in Bailey’s chest. Bailey’s breath broke free in ragged gasps, her spine arching involuntarily from the table, a fragile melody of surrender rippling through every taut fiber of muscle and nerve.

The room tightened around their shared heartbeat—the intersection of science, sensation, and raw, unfiltered hunger pulsing in relentless crescendo.

Lydia’s voice is a soft, hypnotic chant woven into the thick hum of Bailey’s relentless heartbeat. “Your ventricular walls, Bailey… perfectly sculpted. The thickness of an elite athlete, robust yet free of any pathological swelling—a masterwork of cardiac architecture.” Her words float over the electric crackle of the Erwachte Pumpe, blending science and seduction with equal measure.

Pressing her ear firmly against the swelling rise of Bailey’s chest, Lydia feels the convulsive pulses—the thunderous “THUD-DUM, THUD-DUM” reverberating in sharp, magnificent bursts beneath her skin. Each contraction jars her cheek as if the heart itself wields power to move worlds. Bailey’s breathing is ragged now, breaths ripping from her lungs in short, shuddering gasps that mark a body consumed by burgeoning fire. She sweats freely, tiny beads gleaming against bronzed skin, cascading in shimmering rivulets down sculpted limbs and along the curve of her breasts.

Her moans build, thick and wet with desire, sliding free from lips parted in abandon. The sound matches the wild thunder beneath Lydia’s ear, a desperate symphony with no pause. Lydia’s fingers, slick and deft, slide against the slick folds and trembling core, finding with practiced certainty the quivering knot beneath. The rhythm of pleasure rides in perfect tandem with the ferocious beats shaking the room.

With the gentlest cruelty, Lydia’s free hand moves beneath her own thighs, skin flashing heat as she strokes slowly, deliberately. Her breath quickens, mingling with Bailey’s gasps in a tight coil of sound and sensation. The illicit pulse of Bailey’s heart thumping violently against Lydia’s cheek sparks a wildfire beneath her skin—a maddening pulse that echoes in her own blood like a summoned tempest.

Minutes compress into seconds as Lydia’s breath falls into a steady cadence of measured observations and whispered enticements. “Observe how your stroke volume commands the entire chamber,” she murmurs, “each contraction pushing fiercely against resistance, the ejection fraction peaking at an unimaginable intensity. Your heart beats with the force of a wild drum, a tempest contained only by your will.” Her words wrap around Bailey’s senses, fanning flames brighter than medicine alone could kindle.

Bailey’s body stiffens, tense as a drawn bowstring. Her moans twist into sharp cries, her limbs clenching the table with trembling fervor. Lydia’s fingers accelerate in silky mastery, exploring depths and heights, mapping the folds and tides with intimate zeal. The pounding in Bailey’s chest intensifies—a fierce barrage beating against ribs and flesh alike. Every pulse vibrates with brutal might, shaking the sinew until her entire body hums with the promise of release.

Suddenly, the monitor’s steady rhythm distorts—skips shard every third beat, harsh and erratic as a living thing betrayed by its own power. The signal shudders with jagged desperation, rhythms lurching in a dangerous dance that cascades through the speakers like an urgent scream. Bailey’s heart falters briefly before breaking free, firing with savage acceleration that sends hot torrents pulsing through arteries and veins. The rapid onslaught bursts forth, primal and wild, as her heartbeat climbs past limits, a furious tempest blazing beneath vulnerable skin.

The air thickens with charged heat as Bailey’s orgasm crashes over her—a savage wave that wracks body and spirit with undiminished force. Her muscles convulse in waves, ribs heaving violently against the harsh rise and fall of life’s most intimate hammer. She cries out, breath splintered and wet, the sound raw and ragged as it cascades like a roar of primal power.

Drawn into the maelstrom, Lydia’s own senses spiral. The thunderous heartbeat against her cheek ignites every nerve, her body trembling as the wild storm pulses through her blood. Her fingers clutch her own skin, tracing fiery lines as the cadence overwhelms her control. A sudden cry rips from her lips, sharp and unrestrained—a wail of exquisite surrender as her heart spikes fiercely, clocking a wild one twenty beats per minute. Lydia’s mouth crashes against Bailey’s chest, a hot, desperate kiss stolen amidst the tempest of shared climax.

For long moments, the room throbs with aftermath—the primal soundtrack of two bodies shattered and reshaped by fire, by rhythm, by impossible heartbeats exploding beneath skin. Sweat mingles in trails across tangled limbs, breaths rough and rasping in chaotic harmony. Every pulse through the Erwachte Pumpe’s speakers resonates with raw truth, a fierce anthem of strength, surrender, and the inexorable power of hearts driven to the edge of ecstatic collapse.

Within the fragile silence that follows, their eyes meet—fiery pools mirroring unspoken gratitude and the shattering bonds forged in the violent, beautiful storm of this shared experiment.

The furious symphony of wild heartbeats gives way to a gentle diminuendo, rhythms unspooling and settling into harmonious quiet. On the luminous display, the pulses fold back with miraculous swiftness: Bailey’s steadfast organ slows gracefully to a commanding sixty-five beats per minute, a steady, mighty drum carved of discipline and resilience. Lydia’s heart answers in kind, easing to a poised seventy beats per minute, a measured cadence of perfected endurance. The monitors, their cool glow painting the sterile walls in pale blues and greens, attest to the peak form locked within their bodies—testaments of steel and sinew, etched in pulses and blood.

Sweat clings to their skin, thick ribbons gleaming beneath the sterile clinical light. Each breath rises in soft bursts, shallow and jagged yet suffused with a profound sense of accomplishment and fragile vulnerability. The air between them pulses with the faint scent of exertion, a mingling of heated flesh and electric possibility that makes the clinical room feel suddenly intimate, almost sacred.

Bailey’s hazel eyes, bright with equal parts scientific wonder and flushed post-orgasmic warmth, track the scrolling data streaming from the machines. Each wave and spike is a whispered story—of hypertrophied walls sculpted by years of grit, of chamber volumes perfect in balance, of conduction systems delicately poised on the razor’s edge of human limit. Her gaze glimmers with respect, both clinical and deeply personal, as she processes the implications, marveling even as her body trembles lightly with residual thrill.

Slowly, she pushes herself upright from the padded table, the movement fluid despite trembling limbs. Her muscles tighten beneath slick skin; breath escapes in soft moans, the pale light catching dew along smooth shoulders and collarbones. She parts her lips, a fragile invitation ready to spill words—thanks, admiration, wonder—yet the space stills before sound can slip free.

Lydia’s hands, strong and sure, close over Bailey’s delicate face with a sudden, commanding gentleness. The shift is abrupt—a silent declaration in motion. Fingers thread through damp hair, palms cupping soft cheeks with reverence and hunger as she pulls the younger woman forward in one seamless motion. Their lips collide, the kiss igniting in an instant like flint to tinder.

Bailey’s surprise flickers in wide eyes before dissolving into surrender. Her hands rise, tentative at first, then with growing urgency, slipping beneath Lydia’s arms as their bodies press tightly together. Skin slick and bare meets bare in a slick, electric meld, the heat and moisture of their union painting the clinical room in hues of fervent color. The kiss deepens, tongues tracing deliberate, urgent arcs, breathing melding in slow waves that echo the steady thump of their hearts now aligned in intimate tandem.

Their chests press in perfect rhythm, subtle rises and falls that signal new cadences, hearts edging up from resting beats to passionate tempos renewed by their closeness. The monitors, silent witnesses to this transformation, continue their quiet vigil, catching the subtle upticks—numbers shifting gently upward, heart rates dancing in lockstep as breath and pulse intertwine.

Fingers roam boldly, tracing contours long studied in the sanctity of clinical observation but now cherished with raw, personal devotion. Every stolen breath, every shared sigh, weaves a delicate story—two lives merged not just in science but in the vulnerability and promise that follows discovery. The sterile walls no longer separate, but enfold them in a cocoon of shared heat and whispered longing.

Their kiss lingers, a slow burn trailing from mouth to neck, from skin to soul—a silent vow written in rising heartbeats and the tender clasp of arms. It is a moment both triumphant and fragile, the triumphant close of an experiment that began with data and desire and now finds itself blossoming into something more profound and uncharted.

As their hearts beat onward—steady, sure, and increasingly unrestrained—the line between professional rigor and passionate embrace fades into soft shadow. In the quiet glow of monitors and sweat, in the charged silence between moans and heartbeat, a new chapter begins—one of promise, of connection, of bodies and souls entwined beneath the pale clinical light.

#cardiophile#heartbeat#cardiophile thoughts#female heartbeat#heartbeat kink#beating heart#cardiology#female heart#dr. lydia andersson#dr. bailey esposito

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

paramecium fan club rb if you enjoy them and their silly contractile vacuoles

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

As the labor question is steadily and rapidly increasing in recognized importance, every effort should be made to place its “social solutions” upon a thoroughly scientific basis. One of these “solutions” relates specially to the true and ultimate system of currency. I have just received from some unknown friend, probably the author, a small pamphlet entitled “The Labor Question: what it is, method of its solution, and remedy for its evils,” by Charles Thomas Fowler. In it Mr. Fowler says, with great terseness of expression and with truth, that “the birth of the first bill of exchange was the death of the last specie dollar.” Bills of exchange, bank checks, and negotiable paper of all sorts add just so much to the body of the currency; and this issue is unlimited by law, and unlimited in fact, except by the exigencies of trade.[1] They are just as really currency as the specie dollar, the greenback, or the bank bill. A field which has no fence upon one of its sides is not fenced in, no matter how high and strong its fences may be on the other sides. So, the volume of the currency is not, in any true sense, limited by prohibitions of free banking, by a return to specie basis, or by any other means, so long as negotiable paper can be freely issued by individuals; and this free issue of negotiable paper is too useful, and too well intrenched in necessity, ever hereafter to be interfered with. Commerce can be hindered and trammeled to some extent—it may even, for a time, be seriously disturbed—by statute arrangements claiming to regulate the currency, whether by restrictive measures, or by flooding the community with over-issues; but the volume of the currency can no longer be adjusted by such means.

There is, it is true, a certain temporary advantage in the specie basis, simply because it is traditionally believed in, and beliefs or ideas enter into the question of the stability of values. This fact is felt by the advocates of a specie basis. They, and others, would not have so much of the sensation that “the bottom is all knocked out,” if we could return to such a basis, and that confidence would go for something. On the other hand, the sole alternative, so far as seen by the advocates of specie basis, is a fluctuating and limitless issue from time to time of government paper money, with no other regulation than that of an ignorant and changeable public opinion, operated by interested political and financial agitators and wireworkers. Such are the grounds of the honest advocacy, so far as it is intelligent, of a return to a specie basis.

On the other hand, the advocates of paper money and expansion have their side of the truth. They see or feel the fallacy of the claim that specie basis really means any thing but an illusion, knowing as they do that gold and silver are real commodities rising and falling in value along with all other commodities, and that they will in no event make the whole volume of the currency, but will be only a fixed factor—in so far as fixed—along with other changeable factors in the composition of its total volume; a fence upon one side of a field which, on some other side, is an open common. They also see or feel that the best currency would be such as should have some kind of adjusted elasticity, or an expansive and contractile quality, adapted to the fluctuating activities of trade, of which currency is the instrument; and, in fine, that government might, if it knew enough and were honest, subserve by its conceded powers this demand for an adaptation between the needs of trade and the appropriate supply of its instrument.

But, on the one hand, the supposed stability resulting from a specie basis is a mere illusion, and one which is fast being found out and exposed, while the remedy offered by the opponents of a specie basis is not, in fact, the only alternative; and, on the other hand, no existing government does know enough wisely to regulate the currency, and, as a rule, existing governments are not honest.

The political issue about finance, now coming to the front in the United States, and in a degree in other countries, is, therefore, on neither side intelligent or wholly well-intentioned, while yet, on either side, representing something of the truth. The discussion and agitation are, nevertheless, to be hailed as among the most auspicious signs of the times. They signify politics become educational—electioneering a university training-school for the whole people. The community may have to pay dearly for its instruction before it is through with this new war of ideas ; but the right knowledge of the subject will be ultimately evolved, and the war itself will be the opportunity of the true teachers.

I have said that government paper is not the only alternative of a specie basis. It is, however, the only one to which much attention has been given; and the other—that to which I wish to call attention—will need to be carefully elaborated and described from time to time to make it clearly apprehended as, in fine, the science of the subject. I mean a currency and a system of banking based directly on labor and, in a sense, self-regulating; that is to say, regulated and administered by individuals, or by the people themselves, without let or hindrance, without interference or prescription from the government; although beneficent adjustments may possibly take place between the action of the government and this labor system of free banking.

The object of the present essay is not, however, chiefly to define or describe either currency in its specific details, or labor banking as a system. It is rather preliminary to those considerations, and will be confined in a great measure to the simple ascertainment of THE UNIT OF LABOR, which, when ascertained, may be taken as the dollar of the Labor Bank.

Every system of thought, every science which is accurately constituted, has what is technically called its unit, its starting-point, that from which all its investigations take their departure, and to which they recur as regulative of them all. Thus the unit of arithmetic is the numerical unit, or the number one; the unit of geometry is the point, or minim of length; the unit of weight is the pound; the unit of long measure is the foot; the unit of mechanical force is the foot-pound; the unit of mechanical power is the horse power; and the unit of resistance to the transmission of electricity is the ohm. The following definitions are furnished me by Prof. P. H. Van Der Weyde:—

A foot-pound, the unit of force or of work, is one pound weight lifted one foot high against gravitation, the gravitation taken at the surface of the ocean at forty-five degrees latitude. The latter two considerations are, however, practically neglected. The element of time in which the work is done is here left out of the account.

A horse power, the unit of power or of the amount of force exerted or work done in a given time, is thirty-three thousand foot-pounds per minute; that is to say, thirty-three thousand pounds lifted one foot high per minute, or three hundred and thirty pounds lifted one hundred feet high per minute, or five and one-half pounds one hundred feet high per second, or fifty-five pounds ten feet high per second.

A man power is one-eighth horse power; so that a man may lift seven pounds ten feet high per second, or four hundred and twenty pounds ten feet per minute, or four thousand two hundred pounds one foot per minute, or seventy pounds one foot per second.

The French unit of force is the kilogrammeter, one kilogram lifted one meter high, or seven and two-tenths times our unit of force. A kilogram equals two and two-tenths pounds; a meter equals nearly three and one-third feet. A French horse power is seventy-five kilogrammeters per second.

The ohm has been accepted by the British Association as the unit of resistance in telegraph wires and other conductors of electricity; and as the strength of the battery power must overcome such resistance, it has at the same time become the measure of battery strength. The ohm is the resistance which an electric current undergoes in passing through one-tenth of a mile of No. 9 iron wire.

The French unit of electrical resistance is that of one meter of mercury contained in a glass tube of one square millemeter section.

These definitions are introduced here for the purpose of showing the pains-taking accuracy with which the student of mechanics determines his units of measurement,—with which, in other words, he establishes standards, or measures those things by which other things are to be measured,—and to emphasize the statement that Radical Political Economy, or, so to speak, this branch of Social Mechanics, will begin to be rightly constituted as a science only when we shall have established, with equal accuracy, the unit of labor. Unless the measure itself is measured, there is no accuracy, no certainty, no scientific result.

By the science of Radical Political Economy I mean the science of the laws of price-bearing wealth, as wealth should be produced and distributed in order to secure the absolutely equitable exchange of labor and commodities.

I say Radical Political Economy, because ordinary or current Political Economy inquires, rather, into the laws of wealth as it is in fact produced and distributed, with only such suggestions of improvement as do not affect, radically, the present system. I say price-bearing wealth, because there is much wealth which is, or should be, unpriced or priceless; which does not, or ought not, therefore, to enter into commerce at all, in the ordinary sense of commerce. The blessed air of heaven, the affection we bear to lovers, children, and friends, have in them a world of wealth to those who receive them; but they are, or should be, a free gift, uncalculated and unmeasured by price, definite estimate, or equivalent. Our affections are degraded when they are reduced to the level of price-bearing commodities. It is only, therefore, price-bearing commodities which are the subject-matter of Radical Political Economy.

All price-bearing commodities—all, that is to say, which are rightfully such, or which should be such—are the products of labor; and it is the amount of labor concreted in the commodity which is the true measure of its price,[2] This labor is sometimes called labor-cost, or the cost in labor of producing the commodity; and it is then said that, from the point of view of Radical Political Economy, COST IS THE LIMIT OF PRICE. The principle is the same if the price is put directly upon the labor, without awaiting its concretion in a commodity. Hence it follows that, in order to obtain the true measure of cost, and so of price, and so a true standard of exchange or trade, i. e., a true dollar as the unit of trade,—all these being now identified with each other,—we must first ascertain, or in some way determine upon, the unit of labor.

The first and simplest suggestion, in the inquiry after a unit of labor, is the day's work. The hour's work is an important fraction of the day's work, but it is not so naturally the unit as the day's work. The day's work is, it will be found, virtually the labor dollar, and the hour's work accords rather with the dime or bit. But a day's work is, as the matter now stands, too indeterminate to serve as the scientific measure of something else supposed to need measurement.

Work of any kind, in order to be accurately and completely defined, must be determined in three aspects:—

First, as to the length of time;

Second, as to the degree of its intensity or severity;

Third, as to the degree of acquired skill, or ability previously accumulated by other work preparatory to the work now in hand; and as to certain other minor considerations.

The day's work, to be made standard, and to serve as the labor dollar, or the instrument by which all other work may be measured or estimated, must, therefore, be itself defined in all these three particulars.

First, as to the length of the standard day's work. We may take for this purpose eight hours. It is not necessary to insist that this is inherently the true limit of the working day, though much has been said, and may be said, in favor of the division of the day of twenty-four hours into three equal parts,—one for work, one for sleeping and eating, and one for study and recreation. It suffices for our purpose to adopt this period,—arbitrarily, if you will. Certainty is all that is necessary. The “meter,” the scientific yard, serves sufficiently well to measure cloth, whether it be precisely ascertained to be the ten-millionth part (which it is intended to be) of the earth's diameter, or not.

Next, in respect to the severity of the work; and I am here especially indebted to Mr. Fowler for introducing the term intensity, Josiah Warren, recognizing that the character of the work is an element of the problem, used the phrase “the amount of repugnance overcome” to denote the degree of hardship or burdensomeness of labor. The expression is accurate, but, like his pounds of corn as a device for measuring labor, it is cumbersome; and the idea is, for most purposes, better expressed by the simple word intensity. There is another reason why the introduction of this term, as a technicality for the purpose, is important, and fairly entitles Mr. Fowler to claim to have enlarged and improved the technical machinery, in this particular, of the science of Radical Political Economy. I was never satisfied with the moderate degree of success which Mr. Warren—or myself, in my effort to expound Mr. Warren's ideas on this subject twenty-three years ago (see “Science of Society”)—had achieved in attempting to make clear the nature of, and mode of measuring, the elements of work other than the time occupied. I struggled with the difficulty at the time, and have always felt that I partially failed. It is Mr. Fowler's use of the term intensity in this connection which has stimulated me to this renewal of the subject.

The special aptness of this term for this purpose, and the reason why I deem it so important, will appear from the following considerations. Continuity in time, mere forth-stretching in the given direction, is called by the philosophers Protension (forth-stretching); a stretching outward and around in all directions, as in space, is called Extension (out- or from-stretching); and the energy of effort, by which things are, as it were, drawn in upon and by the centering personality of the actor, is called intensity (in-stretching). What we are dealing with is a department of measure—the measure of labor, cost, and price; and the metaphysicians have pointed out that these three modes are the only three possible requisites of complete or exhaustive measurement; so that we may, when we have thoroughly applied them, rest assured that, by such recurrence to first principles, we have scientifically compassed the subject. Hickok, for example, in his “Empirical Psychology,” expresses this proposition in these terms: “No quantity can have measure in any other directions than extension in space, duration in time (protension), and intensity in degree; and when an act of attention has stretched over the limits filled by the distinct quality in all these several directions, it has determined it in all the forms which any quality can possess, and made it to be known definitely in all its measures of quantity.” The subject we are investigating is the quantity of labor; and the question is: Of what does it consist in these three possible modes of considering it?

In respect to time measure, the protensity of labor, we have said all that is requisite at the moment. In respect to its intensity or severity we have ascertained that this is also a proper element of the standard day's work, and so of the measure of all work; and we must now inquire by what standard it can itself be measured or estimated, and how, practically, the standard can be applied. The subject is confessedly a difficult one. All sorts of people put all sorts of different estimates upon the relative intensity or severity of all sorts of different labor. It may almost be said that no two agree upon any point touching the subject. But fortunately science is now sufficiently advanced to teach us how to overcome this difficulty. The statistical and other branches of science have familiarized us with the method of general averages. It is possible to tell with proximate accuracy how many persons will commit suicide next year in London, Paris, or New York; and even how many will choose the razor, how many the rope, how many the pistol, and how many drowning, as the means of effecting death. It will be found possible, in a similar way, when the world wishes to know, to ascertain how many women think washing harder work than ironing, and how many think the other way; and how many men would prefer to work out of doors, and how many under shelter. All these statistics of the details of human labor, and of the estimates which men and women make of the desirableness and undesirableness of every given pursuit and condition, will in the future become subjects of science, and then of practical every-day knowledge and utility; and the labor dollar, then having come into use, will furnish the unit of all such calculations. In that future when equity shall give labor its own, the modes of rightly apportioning the burdens of life will be studied with intensity, and there will be found nothing insuperable in the nature of the problem. The first great step is to convince the minds of men of the desirableness of such knowledge.

It should be borne in mind that, when exchanges of goods shall be made in accordance with a known law of equity based exclusively upon labor-cost, trade secrets, being no longer of any advantage, will be abandoned, and all knowledge of all trades will be thrown open to all people. There will then be greater facility among men for changing their occupations, and for gratifying their tastes in their pursuits. This change will also enable people to know far better than they now know what labors they really like best, and are willing to do at the cheapest rate. There will then grow up a legitimate labor-market, and all kinds of labor and products will be tendered at the minimum price as measured by the average estimate of the degree of severity of the labor involved in them. In other words, every act of purchase and sale will then be the result of the votes of two parties on the relative repugnance and attractiveness of the two varieties of labor involved; and the whole body of trade will be a continuous canvassing of all such questions. It is so now in part, and except that ideas are confused on the subject; that each party to every trade considers himself entitled to take advantage of the other, which is an illegitimate element—as much so in principle, as the sword or the slave whip thrown into the bargain; and that no labor dollar, and therefore no instrument of adjusting labor-cost, has hitherto existed.

Assuming, then, that by the prevalence of equity, or the true interchange of equivalents in labor-cost, we had a full supply of everybody's estimates of every kind of work in respect to its relative repugnance or attractiveness,—its intensity, in fact, as hard or easy work,—it would be easy to strike an average which should be very exact—the true par of labor intensity; all above that average being work of extra or plus intensity, or above par, and all below it being work of minor intensity, or below par. We have not, it is true, as the case now stands, the necessary data for establishing the exact par of labor intensity; for the world has not hitherto thought it worth while to study such facts. The best that can be done therefore, to begin with, is to assume an average which will approach in some measure to accuracy, and to go on constantly eliminating error and arriving at a higher decree of precision.

Everybody has some idea of what constitutes an ordinary or average degree of hard work. We may now, then, without attempting to fix the idea any more definitely beforehand, further define the labor dollar as a day's work of eight hours—of course whether male or female labor—of the average degree of severity or intensity. I think the bare abstract idea of an average, or par, is all that is needed, and that it is better than Mr. Warren's corn measure. We all know sufficiently well what we mean by “the usual degree of health," and do not have to add "as well as Mr. A or Mr. B;” and, if we should undertake to settle the matter more exactly in that way, we should most likely diverge at once into a discussion over the question whether Mr. A's or Mr. B's health was of the average degree; thus demonstrating that the bare idea of the average is more definitely fixed in our minds than the particular state of the health of any individual. This view does not, however, antagonize the previous suggestion that the extended and systematic observation of details will ultimately render the abstract idea still more definite.

If parties, in negotiating an exchange, regard their labor as of the ordinary degree of intensity,—which would occur in the great majority of cases, especially under the criticism of a worldful of appraisers,—that determines the point without further parley. If, on the contrary, one or both differ in their estimate from the average, that is matter of negotiation. If one too much depreciates his labor, it will become, with culture, under this system, matter of courtesy to insist on raising the estimate. While, then, ordinarily a dollar note will be paid for the day's work or its produce in a commodity, the price and payment may go up to a dollar and a half, or down to the half dollar, or may deviate to any other- degree, the dollar serving in every case as the unit of comparison,—as, in a word, the standard of labor-cost, price, and labor-value, which all come to be identical; value meaning in this case, not utility, but the buying-capacity of the dollar.

To illustrate: suppose a community reduced by any cause to the primitive condition of barter. Instead of the poor device of the shinplaster,—referring for its measure of value to the silver or gold dollar, which has taken its departure and is no standard,—let the labor note be substituted. Miss Smith undertakes the teaching of the village school. She will teach eight hours a day, and she estimates her labor as neither above nor below the average degree of intensity as hard work. This, then, being exactly the value of the labor dollar as above defined, Miss Smith charges one dollar—a labor dollar—a day for her work. She has an average of twenty pupils. For each pupil the parents become, therefore, indebted to Miss Smith the twentieth part of a dollar, or one half labor dime, or five labor cents, per day; and they pay her in their own labor notes, or in the labor dollars, dimes, and cents which have come into their hands from their trade with others. The labor money bills only differ from every body's individual notes written on common paper in the fact that the storekeeper or postmaster has got up his own notes in better style, printed and perhaps vignetted, and issues them in the place of the common written scraps of paper.' These he keeps in his safe instead, as his specie basis, they being the immediate representative of the labor of the village, so far as it is in market. As fast as the work promised is done, or its equivalent given in products, the notes are redeemed and cancelled, or re-issued, and the transaction is ended.

In this manner Miss Smith gets her entire pay in good labor dollars. These will command every body's work and buy every thing produced in the village. Dealing with the outside world involves an extension of the problem which will not be considered at this point. The school teacher may, in turn, to the extent of her credit, and wishing to anticipate returns, issue her labor notes, transmutable into labor dollars by the village banker —the postmaster or store-keeper, as before stated. In this manner she, and every one in the village, becomes a capitalist to the extent to which their neighbors have confidence in their future ability and intention to fulfil their promises; and so, able to create loan's for themselves at any moment to this extent; checked in the first instance by any lack of confidence on the part of the immediate neighbors, and then on the part of the village banker, who must have confidence also before he will receive the individual's labor note and replace it by his own issue. Thus a healthy and continuous vigilance will be exerted over this otherwise perfectly free creation of the labor bullion of our new banking system. Risk and actual losses will, however, occur ; but they will be reduced to a minimum by the natural working of the system; and the village banker will become an insurance agent to cover them, being allowed to increase the currency beyond the bullion in deposit the slight percentage found practically necessary to that end.

Apart from this percentage to cover losses,—which will be kept at the lowest, as it will be added under the immediate inspection of the whole village, each individual being constantly taxed his proportion of every loss,—the village banker is not to be allowed to issue a single labor dollar for which he has not the same amount of labor bullion—the labor notes of the people—in deposit; including, however, his own labor notes covering his services, and issued on the same terms as those of any other citizen. Every over-issue should be deemed a fraud, and prevented or remedied by well-devised checks upon the conduct of the banker,—such as numbers on the bills issued, reports and inspections of committees, etc.,—until confidence is so established as to dispense with unnecessary caution. The banking office will be open to competition in respect to the best management, like any other business. If a dozen bankers spring up in the village, no matter.

Another element remains to be added in the constitution of the labor dollar,—one which has been alluded to above, and then purposely postponed until now. This is what we will technically call the Extensity of the day's work,—an element which extends beyond, or goes outside of, the particular day upon which the work is to be done. This element is the acquired skill of the laborer, secured by previous labor fitting him to do the work; the wear and tear of instruments or tools of his own, which he brings into the work; particular risks of any kind assumed by the laborer, etc. This item is fixed also by averages and the mutual estimates of the parties contracting.

Prior labor giving skill is to be estimated upon the same principle as other labor; but, the cost being distributed by estimate to all who will be ever likely to avail themselves of the skill, it becomes generally a small item in the individual case: such as it is, however, to be settled by the estimates of the worker and employer, or tacitly covered by the general price demanded for the day's work. So with the other matters included under this head. All legitimate risks are legitimately covered by an augmentation of price.

It is a curious working of this equitable system of exchanges that, while acquired skill involving prior labor is an element of the price of labor, superior natural ability—“the gift of God”— is left wholly out of the account, and does not in any manner augment the price. This is a point which is more frequently than any other misunderstood, and which, when understood, is most likely to meet with objection from new investigators of equity. A little close attention to it, however, will remove all difficulty. It is undoubtedly true that superior natural ability does give a natural advantage, which the possessor may, if he will, and which at present he does, avail himself of in disposing of his labor. The question now is, however, whether he ought really to do so; or, in other words, whether the gift of Nature to the individual is something entirely for his selfish individual benefit, or something in which his weaker competitor especially, and the public at large, should participate.

It is certain that the principle of equity, as rightly defined,—the exchange of equivalent burdens, or of equivalent amounts of repugnance overcome,—gives nothing for that which costs nothing. The handsome woman degrades herself if she makes a charge for exhibiting her beauty. It is wealth to the world, as it is also to herself, but not price-bearing wealth; not an object of ordinary commerce or trade. Ought it not to be the same with superior natural talents and endowments of all kinds? On the race-course and in the prize-ring, where the object is—as here, in respect to equity—to neutralize all undue advantages, it is not merely the swiftest horse or the strongest man, pure and simple, who takes the prize. All advantages are first equalized by granting to the weaker party compensating advantages. The “light weight,” when pitted against a bigger man, has a due concession made to him on account of his obvious inferiority.

Should not laborers, in seeking equity for themselves, be ready to abide by the behests of equity throughout; when it works against, as well as when it works for, them? Should not the world's workers come to be as generous, as honorable, as just, at least, as racers and prize-fighters? No pugilist would call it a fair fight when a big fellow knocked down a little one merely because Nature gave him the superior ability; merely, in other words, because he could do it. No gamester would refuse to give odds to one less versed than himself in the game. Curiously enough, these are almost the only people who have ever been dealing with the question of what is fair play in any competitive engagement of man with his fellow. Ordinary political economy never asks the question, but only inquires to what extent, and by what means, the big fellows actually get the advantage; what are the laws and operations, in other words, of the natural tendency to advantage-getting.

In those departments of life where courtesy is established, there is no doubt on this question. If a weak woman burdened with a child is allowed to stand in a crowded place, and strong men sit at their ease, it is justly regarded as an outrage upon decency; and yet the strong men would only be availing themselves of their natural advantages.

In a word, on principle, the question is settled beyond all doubt that equity, in establishing prices, grants nothing on the ground of natural superiority,—therein concurring with the principles of fair dealing as understood in games, and of courtesy as understood in society. But still, with our present habits of thought, the verdict may seem a harsh one; and many persons will perhaps be more readily convinced if made to see that the principle will work well in practice, than by the mere sternness of the logic. This well-working of the principle is also readily shown. But first, let us conclude our definition of the labor dollar as the measure of radical equity.

The labor dollar is then, in fine, a vignetted paper representative,—or its equivalent,—signed and issued by a labor banker, of a day's work, of man, woman, or child, of eight hours' duration, of average intensity and average extensity.

The general aspect of the labor dollar may be similar to that of a current dollar bill more or less elaborately devised. Paper will be the ordinary material, although it would not cease to fulfil the conditions if some other available substance—as parchment for instance—were used instead. Its cost and the labor of signing, issuing, cancelling, renewing, etc., belong to expenses, and can be repaid to the banker, equitably estimated, along with all other labor.

A promise of labor to the same amount signed by an individual not a banker, not vignetted, etc., would pass under the more general designation of “a labor note.” Together, and with all accessory commercial paper of the same order, they would constitute the labor currency.

The labor notes of the people, in the safe or vaults of the banker, securing him in making his promises to render so much labor, or its equivalent in products, are what I have denominated labor bullion.

Trade or commerce conducted on this basis may be denominated labor trade; and the transactions of this trade, with the ruling rates for different kinds of labor, will come to be rightly known as the labor market; and the labor rates of every species of men's and women's labor, down to minutiae, will be regularly quoted.

The radical, indeed the revolutionary, difference between a currency based on this simple device and any previously existing currency may still escape the reader, unless he again reflects that the labor dollar means something defined, and therefore definite, and that the current dollar means something wholly undefined and indefinite. Consider the difference in this respect between a common token, such as a theatre ticket or a railroad ticket, and a paper, or even a silver, dollar. The token obtained to-day will purchase a seat in the theatre or the car to-day, tomorrow, or six months hence: that is to say, it represents a definite something, or, in other words, a fixed and ascertained purchasing-power. Not so with the dollar, whether paper or metallic. You may know what you can buy with them to-day, but what they will procure for you to-morrow, a week hence, or six months hence:,you cannot know, as their value may have fluctuated within any limits; in other words, they have no fixed or ascertained, or ascertainable, purchasing-power. The labor dollar has, then, the character of the fixed token, as contrasted with that of our present currency; or the character of a measure which is itself measured, as contrasted with an elastic yard-stick, or the hand or foot used as a pound weight.

In an article on finance by Mr. McCulloch, ex-Secretary of the Treasury, he says:

“There being but one universally recognized measure of value, and that being a value in itself, costing what it represents in the labor which is required to obtain it, the nation that adopts, either from choice or temporary necessity, an inferior standard violates the financial law of the world, and inevitably suffers for its violation. An irredeemable, and consequently depreciated, currency drives out of circulation the currency superior to itself; and if made by law a legal tender, while its real value is not thereby enhanced, it becomes a false and demoralizing standard, under the influence of which prices advance in a ratio disproportioned even to its actual depreciation. Very different from this is that gradual, healthy, and general modification of prices which is the effect of the increase of the precious metals."

What is here said of the relative fixedness of paper and metallic currency, which would be in a degree true if the comparison were with a currency to consist of the precious metals and nothing else—which is not pretended,—applies as a condemnatory criticism upon all systems of finance which exist or have existed; and the encomium can only be conferred rightly on the labor currency, which has the characteristics insisted on in a still higher degree than the metals alone would have them.

In the above definition of the labor dollar the day's work of a child is estimated at the same as that of a man or a woman. This will be apt to strike the investigator at first as erroneous, but he has only to recur to the principle to perceive that it is strictly accurate. The severity, or repugnance overcome, in keeping a child eight hours intensely at work, is almost sure to be as great as, and is most likely to be much greater than, that of so employing the time of a grown person; and by our principle, it is this severity endured which is to be compensated or equalized by the price paid for the labor. Such is, in other words, precisely all that price can rightfully mean.

What, in the next place, would be the working results of this principle upon the labor of children? Just this: as children's labor would have to be paid as much as, or more than, that of grown people,—except when employed at those light and pleasing labors which for them would resemble play,—no employer would engage children for hard and unsuitable work, except in cases of urgency or peculiar necessity; and then he would submit to compensate them appropriately, according to the principle. Children would then be, as it were, driven out of the labor market (except in the emergencies above referred to); which means, however, nothing more than that employers would prefer, if practicable, to secure the heavier and harder variety of labor when it was at the same time lower priced than the other; and secondly, that children would be thereby left free for acquiring education, and for play or untrammeled exercise, which is precisely what should happen. In other words, children and grown people would be relegated, respectively, by the working of a simple principle, to their true places,—a drift which would co-operate exactly with what is now the effort of wise and benevolent parents and guardians.

The case of children conducts us back to the question, reserved above, of the similar working of the principle in denying pay for superior endowments, which, as a portion of natural wealth, are by the theory non-price-bearing commodities. Here also it will be found that the effect is quietly to force every body—not now children alone—into their true places; being in fact, thereby, one of the greatest of social solutions. Under the principle, the best endowed and most efficient labor comes into competition with inferior labor in each special branch, not, as now, at a higher price, nor even at the same price, but absolutely at a lower price. Of course, then, it will force itself in, and force the inferior labor out. Let this be well understood. He who should have the greatest natural fitness for a particular kind of work, having greater facility in it, will—with some exceptions only—have also the greatest attraction or fondness for that kind of industry. His estimate of its intensity will therefore be less than that of other men. In other words, it will not be as hard work for him as for them, and, therefore, under this new principle, his price will be less. Of course, then, he will be preferred, and those for whom it is harder work or more burdensome will be set aside. The very best workmen will first be taken up by the employers; then the second best; then the third best; and, finally, and under necessity only, the poorer qualities; which, however, if called in, will be paid the higher prices, as in the case of the children. There is, even as matters now stand, a natural preference, of course, among employers for superior workmen; but this preference is nearly neutralized, and sometimes inverted, by the fact that such labor must have the largest prices; so that poor laborers are about as readily retained, and sometimes more so, than the superior ones, whereby the survival-of-the-fittest principle is defeated, and the general quality of products depreciated.

This paying of the best workmen the lowest prices upsets, of course, all existing notions. It is a difficult point both for unphilosophical and for selfish minds. It is, nevertheless, not only abstractly right, but replete with the best possible results. It is on the road to the reduction of all price to zero, or to the time when all labor shall be play, and shall be exchanged for love without price. But far short of this, and immediately, these results follow: 1. All labor will be performed—as a rule—by the best workmen and with the utmost efficiency, and, consequently, all products will be carried up to the highest excellence. 2. All prices will be brought down to the minimum, or to the very cheapest at which the labor, or the product, can be afforded —tending to place both necessaries and luxuries within the reach of all, 3. Every body will be gently and unconsciously forced into just those pursuits for which they are best suited, and for which they have most liking; in other words, Attractive Industry will be in a great measure realized. What could be asked for better than all this?

Upon this third point a word should be added. The inferior workman, forced out of an employment, may and often will prove to be the superior workman in some other; so that to be driven out of the labor market only means, in fact, being transferred to something better, until the whole world shall be employed at just that which it likes best to do.

A fourth result, perhaps the most important of them all, will be to substitute a PRINCIPLE for the settlement of prices instead of the system of universal higgling and overreaching which now prevails; a civilized and scientific, instead of a barbarous, method. If war may be defined as an inflammatory social fever tending to the surface, trade for profit, by bargaining, may be regarded as the low or typhoid form of the same, a disguised and diffused fever, a state of modified war of all against all. This greatest effect of equity would then be to substitute interstitial peace for a universal state of interstitial warfare in society, opening the way to all kinds of beneficent cooperation in the place of an antagonistic individuality.

It must not, however, after all has been said, be concluded that the mere operation of the principle, “labor-cost the limit of price,” will fulfil all the conditions of social harmony, and supply of itself the true social organization. It is simply a plank in the ship, or, if you will, the keel; but it is not the whole structure. Nor will it prove, taken alone, altogether satisfactory. A society constituted merely under the operation of this principle would, indeed, secure a genial and beneficent equity, but it would also lead to a certain dead-levelism of conditions which would lack an element of picturesqueness and variety which the human mind also craves.

Nobody could ever become very rich; but the level prairie, or the fertile plains of Lombardy, would prove dull, if the whole world had nothing else to exhibit. Security of condition and a sense of prevailing justice in life, while they are a basis of happiness, are only a basis. The human soul has legitimate aspirations for distinction, preeminence, largeness of individual environment, and the means of great and beneficent achievement, which may demand the possession of exceptional wealth of the acquired and price-bearing variety, as well as mere natural endowment. These aspirations the existing order of society does, to a considerable extent, gratify; but it does so at the expense of a general denial of equity, and of a consequent all-prevalent irritation, ending in the insecurity of the very wealth so acquired. Equity is, therefore, a question of method, of economy, and of security, as well as a question of the just distribution of wealth. The demand for some opportunity for larger acquisitions than are afforded by mere equity is, nevertheless, a true voice of the soul, and the supposition that the doctrine of equity completely forbids any such aspiration is one of the greatest hindrances to its acceptance. There is a secret repugnance to the doctrine left in the mind, despite the logical cogency which may compel an intellectual assent. This comes, however, entirely of misapprehension. It is not essential that a devotion to exact and technical equity should predominate in all human transactions. What the doctrine affirms is merely that, by bargain and traffic regulated by equity, large fortunes could not be acquired, while every body under the operation of that principle might become measurably rich. It stops at this. It does not concern itself with any other class of transactions among men, neither denying nor affirming the possibility of acquiring exceptional wealth by other methods. This particular doctrine is merely a branch of social science, and does no more than merely furnish the law of a single variety of human transactions. We must then look to social science at large for the answer to the question whether there are methods of gratifying the desire to wield great accumulations of wealth, other than trade on the price-bearing basis, and not antagonistic to commercial equity. As a student and teacher of social science, I can only, at this moment, aver that such methods exist within the scope of a true social order, and such as tend to even larger accumulations in rare instances, and to a more undisturbed possession, than the existing order renders possible. That subject, however,—the possibility of exceptional instances of great wealth, especially if administered for- beneficent uses, in a community whose trade is regulated by equity,—is a distinct one sufficiently extensive to require separate treatment, and must be, for the present, disposed of by this mere mention.

Let it be observed that no consideration whatsoever is given in this article to the practical question,—to the possibility, that is to say, and to the methods, if possible, of introducing the labor currency; of engrafting it, so to speak, upon our present complicated civilization, and making it the actual substitute for all other systems of currency. It is the theoretical question only which is here considered—the question of what is intrinsically the right and true thing, irrespective of its feasibility. The practical question must be considered also, if a demand arises for it, in a separate paper.

[1] The terms currency and money are generally used as synonymous. It may be well, however, to discriminate. Boucher insists that the term money can only apply to that which rests on the public confidence at large and is intended to continue in circulation, whereas checks, drafts, etc., are intended to serve on special occasions for the convenience of individuals. There is no objection to noting this difference, but it is not vital. It is still true that all these other forms of paper promises which enter into commerce, and effect exchanges, and represent values, and which in the aggregate are far the greater part of such representative, are a portion of the currency properly so called. Money is a distinct part of the transportation of a country; but common roads and carriages and every other means of conveyance, down to the dog cart and the legs of the individual walker, are also a part of it, and in the total aggregate must be taken into the account. So, in respect to the currency, checks, drafts, etc., must be taken into the account as well as actual money, when the question is of arbitrarily limiting the total bulk of the machinery of commercial exchanges. A friend, to whom the manuscript of this article was submitted for examination, takes the following exception, in a letter to the author, to the latter’s statement that the issue of currency is unlimited by law. “The Massachusetts statute-book, as well as those of most of the other States in the Union, contains laws prohibiting, under penalties of fines, the issue as currency of notes, bills, checks, and orders, except such as are especially authorized by the State, United States, or British Provinces of North America. True, these laws are not enforced; but this is because the speculating classes have no occasion to demand their enforcement. They are very glad to avail themselves of checks, etc., so long as they can do so under the old plan; but, should any one attempt to issue such money as you propose at a rate of discount just high enough to cover the expenses of issue, thus beating the bankers on their own ground, the laws would be enforced at once. The bankers oppose every effort to have them removed from the statute-book.”

[2] It is the striking peculiarity of Radical Political Economy that it emphatically denies that value, in the sense of utility, or the degree of the purchaser's need, can rightly, i. e., equitably, have any thing whatever to do with settling the price; the price depending (equitably) wholly and absolutely, and exclusively, on the amount of labor invested in the product. I cannot stop here to expound this important doctrine, which is nevertheless matter of demonstration when the subject is analyzed to the bottom of it. I allude to it because, if the reader suppose that this essay is dealing with price as compounded, in an uncertain way, of labor-cost and utility, as in ordinary political economy, he will entirely mistake. Under the methods of Radical Political Economy, the urgency of the purchaser's need no more affects the price he is to pay than it affects the length of the yard-stick by which the goods are to be measured. The price is a fixed quantity and remains the same whether the article ever finds a purchaser or not. If it proves unsalable at its price, it is withdrawn from the market, and, in whatever way it may be disposed of at any other than its fixed price, the transaction is understood to be outside of equitable commerce. Equitable commerce is, in this respect, merely like the one-price store.

#equitable commerce#labor notes#labor theory of value#money#mutual banking#economics#anarchism#anarchy#anarchist society#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#resistance#autonomy#revolution#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#daily posts#libraries#leftism#social issues#anarchy works#anarchist library#survival#freedom

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gut Feeling Forces

The effects of mechanical forces and shape changes examined at the cell level in the small intestine – increased contractility has different effects on undifferentiated and proliferating cells depending on whether they are situated in the villi or the crypts of the organ

Read the published research article here

Image from work by Taylor Hinnant, Wenxiu Ning and Terry Lechler

Department of Dermatology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, USA

Image originally published with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Published in PLOS Genetics, March 2024

You can also follow BPoD on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Human Cell Tournament Round 1

Propaganda!