#polemic imagineer

Text

[GANGSHUFFLE]

The Mutinous Cabal

Marvel Capital's crew of self-proclaimed watchdogs. They keep an eye out on whatever's brewing on the city's notorious criminal underbelly- with a little cut of the pie, of course. Gotta keep their heads above water, after all.

Posing as their figurehead is the ever charming and mysterious DEBONAIR DESPOT, an ex-soldier turned vigilante. He's a quiet, dedicated man with the energy of a restless cat. Of course, when you have the ability to see the future, wouldn't that make you restless as well?

The real boss hiding behind the curtain is SCRUTINOUS SCOURGE, the visionary behind Marvel Capital's creation. He's madly in love with his city, and rumor has it he's made a deal with a Terror to secure her flourishing in exchange for his sight. God complex? Seems pretty simple to him!

With their intel guy, COGENT DEALER- a former Dersite agent- and medic turned heavy muscle, HARMONIC BASTION, the Cabal keep the shadows in line and out of the light of day. It's their city.

Team Ace

A gang of dishonorably discharged ex-coppers, teamed up with the goal of cleaning up Marvel Capital's dirty laundry. Little do they know, they've already passed their hero arc. Everyone else starts looking like a villain when you think you're the protagonist, after all.

Leading their rather suspicious charge from the shadows is the obstinate POLEMIC IMAGINEER. They say that cute face hides the wrath of God.

Functioning as the 'man in charge' is ACEPHALOUS DICTUM. But his friends, and his co-workers, and.. Well. Everyone calls him ACE DICK. Tired father of one girl and two grown-ass men.

And every ragtag group needs a poster boy, and for Team Ace that boy is the grown-ass man, PROSAIC STEWARD. He's. Uh. Been in a rough spot since a.. Particular even that happened before he was kicked from the Marvel Capital Police Department.

They seem at odds amongst themselves often with their goals- but when they pose as a threat? Shit just gets REAL.

The Flux

The top yakuza syndicate in the Marvel Capital. Having taken over during a vulnerable time for the city, they've had their claws dug deep into the corner of every block in every district. No gang seems stand a chance against them and their wide array of magical abilities- utlizing Shadow and Temporal magic alike.

The Flux use number based aliases, with their real names mainly unbeknownst to the public. But two in particular send shudders down the spine of even the most notorious oyabun in the city's underworld.

Number Six, DEOR. The big boss himself. A reclusive man who stands firm in his ideals, hellbent on sucking Marvel Capital dry before running it into the ground. Some say he's got a powerful Terror pact- other's claim he's a naturally gifted Green Sun mage. No one's lived long enough to determine for sure which one's true.

Number Seven, YUSHA. Deor's personal lapdog. He's never seen without a smile, nor without his Crowbar. People who know him say he's got an odd air to him, as if he doesn't even know what's going on around him. Regardless, that doesn't stop him from swiftly fulfilling his orders with great efficiency.

This rainbow of thugs will stop at nothing to claim Marvel Capital as their own. It's their land.

City Officials

Every city is only ever as good as the people in charge of it. Luckily for the Marvel Capital, capable hands work hard behind the scenes to keep the place livable for the average citizen- determined to keep the peace. Even if it means occasionally having to play by the Cabal's rules.

The former Mayor, WINDSWEPT VILLAGER, keeps a well trained eye on the city's archives. After an attempt on his life during that left him disabled, he's stepped down from his position. Nevertheless, he continues to work behind the scenes- playing as an informant and confidant for the current Mayor.

PEACEKEEPING MAYOR is the current head honcho serving in office. Having been an ex-archagent like Villager, positions of great responsibility (and stress) are nothing new to her. She's a stubborn woman with a who will do anything for the city- going so far as to work with the Cabal to keep as eye on what goes on in the shadows.

If the Mayor watches over the city, who watches the Mayor? That duty of course goes to ASSIDUOUS REGIMENT, the head of the City Council's security department. Having failed to protect Villager before, he's sworn to himself to not allow that to happen ever again. He's a stiff, stern figure, but below that tough exterior, he's got a good heart.

The three of them work day and night trying to maintain the balance of the city- but everyday it grows clearer it was made to be less of a home and more of a playground.

#the felt#midnight crew#problem sleuth#homestuck intermission#the exiles#homestuck intermission au#mspa#fan art#gangshuffle#character refs#mutinous cabal#scrutinous scourge#debonair despot#cogent dealer#harmonic bastion#team ace#polemic imagineer#prosaic steward#acephalous dictum#the flux#1 izashi#2 aiyana#3 haoyu#4 cezar#5 arata#6 deor#7 yusha#9 lash#10 daan#11 matija

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

----------

PI: Im afraid I just dont understand why Ace would be mad at me.

PI: I dont know what I did wrong.

PS: you. kinda killed a guy! in broad daylight!

PI: To be fair the poor sucker in question had Flux relations.

PS: what the fuck maggie he was just their mailman

PI: Suspicious mailman.

----------

PROSAIC STEWARD: A former superstar in the police force turned pathetic mess of a... Vigilante..? Watchdog..? Whatever Team Ace is trying to be. He's got a pretty face and a good heart, but he's a jaded, tired soul. His life's been full of mistakes, but he still hopes one day the world'll be better place- he just doubts he'll be able to help make it happen. Last time he tried help... Well, he tries not to think about it too much.

POLEMIC IMAGINEER: An ex-forensics officer kicked off the force for his effective but... Unethical methods. He's constantly stuck in a walking daydream- the world seemingly flows with his imagination. It makes him dettached to certain concepts, like people. Or logic. Or consequences. He doesn't care about means as long at it makes the ends happen. After all, Team Ace needs someone with the spine to eradicate all the crime in Marvel Capital.

#gangshuffle#homestuck intermission#prosaic steward#polemic imagineer#homestuck on main#mspa#PI: Anyone could be capable of crime#PS: what about me#PI: Not you.#PS: aww is it because ythink im good or somethin?#PI: No it is because you are a sad wet little dog.#PS: woof :(#problem sleuth

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

A little bit emotional about this stackexchange post where someone, presumably a kid, teaches themself C using K&R the c programming language.

and so it's like. Outsider art almost. K&R doesn't have many large examples, so it's somebody figuring out programming idioms from first principles basically. And like--yknow--it's all there. it's all fucking there!

It's like how people talk about meeting aliens and them playing go and they might play some things differently but they'd know a 3-3 invasion.

idk. for some reason this has got me choked up all evening. K&R hands you like. here is how to reason through the execution steps of an if statement, but iirc it doesn't have any examples of complete code. It sure doesn't hold your hand on like, idiomatic code. and so you hand that to somebody and they say okay and.

they write fucking CODE. they write fucking CODE and you look at it and you go this isn't idiomatic but dear god. you have fucking written CODE you have felt the computer in your bones. i have never met you and yet I know you.

#sometimes a novice writes code and it's like ok this looks superficially right but there's still some gaps in your ability to#reason through code. and that's fine and normal. the 'learn to run the code step by step in your brain' is a skill that you learn#but this user has learned that. you can see them thinking about the steps they want the machine to do and how to express them in C.#it's beautiful. it's really really beautiful to me.#you could imagine this as an anti-ai polemic THIS IS REAL CODE but it's not#ai is fine. but look at this. isn't this code fucking beautiful.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Never ended up adding this, but:

I don’t believe DM ‘woobified’ Thomas Cromwell, but I see some sort of marriage of narrative in his own biographical apologism & the depiction in Mantel’s series and its adaptation that filed off some his sharper, less palatable, edges, including the TV adaptation (if not literal marriage, then certainly a feature now of this sort of Cromwell-focused subgenre/...fandom?). It’s Cromwell holding a kitten that we see, not Cromwell introducing a bill for the utter abolition of sanctuaries, Cromwell gently scolding an imperious Anne who insists Thomas More should be tortured ( ‘we don’t do that, madame’), rather than Cromwell as the orchestrator of the rather torturous executions of John and Alice Wolfe. In so many of these scenes, the characters opposite Cromwell feel like strawmen-- an irony, from an author that so often derided that infamous author of so many strawmen arguments where he came out the moral and intellectual victor, himself...

I also don’t think the criticism of misogyny as it concerns AB’s character in this series, the original source material nor the adapted TV series, is proportional to how eye-watering it was (dismissed because she’s so auxiliary, maybe...?). There is literally a scene where Anne tries to facilitate the seduction (and probable rape) of a teenage girl (presumably inspired by a dispatch of Chapuys in which he does not even report that there’s any rumor of this plot, just that he believes she might do so, that it is the goal and potential method of the isolation), as Cromwell stands on in silent, long-suffering, morally reproving judgement (which emerges as a pattern, another scene later or before is him being the calming voice of reason as she squawks in outrage at the wording of the Act of Succession). Paired with the absolute Mary Sue gender-equivalent of this character (in TMATL, even his own daughter-in-law wants to fuck him), it’s just nauseating.

#his praise of mantel's work validated it in some ways#particularly in academic circles to the point she was invited on a panel of historians for a documentary about AB#so...#yeah. idk. i don't think there's anything wrong with depicting moments of vulnerability; either#but where's it afforded to any others in the text?#SA tw#*vulnerability and humanity#the book as well ......there's way too much 'oh but that was period-accurate misogyny'#of course there was 16c misogyny but part of critique is questioning the narrative necessity of the scenes that feature that#what was the narrative necessity of cromwell imagining himself stroking her breasts in the TV adaptation?#or the duke of suffolk in the book saying he knows for a fact she practiced oral sex on dildos in france? like.................#mantel's 'AB was not a victim' manifested into material that implied at almost every narrative turn that every misogynistic narrative#about her that existed from the time of contemporary report to polemics during her daugher's reign#was justified and reasonable#cromwell doesn't think very highly of suffolk and obviously neither does mantel but the implication of the scene isn't that that's not true#but that he just can't say it.#*shouldn't say it rather#since cromwell just advises him that her becoming queen is inevitable

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking about the effects of Jayce's miscarriage in both him and Phoenix

#like i imagine it happened in his third month so both of them had time to get attached to the baby#surprisingly phoenix had a good reaction when jayce told him he was pregnant because deep down he wanted to be a father#even if 1- his Bad Boy(tm) personality didn't allowed him to say so 2- he's supposedly straight and in a relationship already#so the revelation would be quite polemic#(alessandra didnt really mind he cheated on her because shes actually a lesbian and was desperately looking for a chance to break up)#anyway phoenix took responsibility and had a Very Serious conversation with his parents and friends that he was going to be a father now#and jayce also did#so they were like. excited. very. and then it happened; he lost the baby#jayce fell into depression and his grades lowered#meanwhile phoenix became a shut in and stopped being sociable#they had discussions because they bought a pacifier and jayce wanted to throw it and phoenix wanted to keep it#but these discussions ended up with both of them crying; hugging and saying sorry#help them they are suffering#oc talk#ask to tag

1 note

·

View note

Text

tips to level up your writing skills

1. read, read, read

okay, I know, everyone keeps saying it... but it's true, and I truly believe the more you read, the better you write, because you come across different writing styles, different voices, new characters, and worlds. This applies to every writer, from amateur to professional.

2. practice makes perfect

another cliché, right.

but hear me out: I feel so much more confident about my writing skills when I write daily, rather than when I write a bit occasionally. you get lots of work done, see your book coming to life, and get better at it.

3. create an outline before you start writing

guysss, I know many people like to go with the flow, but I would recommend planning your novel before writing it, especially if it is one of your first projects.

when I started, I refused to plot my novel because I thought it was a waste of time, and I couldn't plan it all ahead. turns out that I could never finish my novels, because I started to get lost in the plot. as most of you may know, I LOVEEE to plot now!

4. use active voice instead of passive voice

passive voice is alright sometimes. I like to use it, too. but to create an immersive experience for the reader, you should go for the active voice since it creates more impact.

see something like this:

"the letter was written by Marcus who had tears in his eyes." VS "Marcus wrote the letter with tears in his eyes."

such a basic example (don't judge me!!)... but can you notice the difference? it seems so much more expressive.

5. avoid using overly complex language

repeat it after me: short. sentences. are. valid.

don't overcomplicate it! I know it's tempting to write huge sentences sometimes and make your book seem more complex and professional, but sometimes it just doesn't come out as expected, and we end up exhausting our readers.

6. don't just for yourself

this can be a polemic topic. it's quite common to see people saying you should write for yourself, but let's be honest here: if you're trying to get your book published, you should have your target public in mind while developing your book. knowing your audience to know what works and what doesn't work is extremely important. but hey, you must also enjoy what you're writing!

7. use dialogue!!!

I find dialogue so important, and I love it so much! ensure you develop a distinctive voice for your characters to make them seem real to the reader. also, if possible, read the dialogue out loud and imagine if it would work out in real life.

8. don't be afraid to use metaphors

metaphors will turn a "basic" work into something more sophisticated when applied in the right places. you might want to avoid overusing it because it can ruin the experience, but it's something up to you, and what feels better to you.

9. research your topic before writing

okay, this is pretty self-explanatory. if you're writing about a topic or a location you don't know much about, avoid making assumptions or clichés. instead, do some research, take notes, or even ask chatgpt questions to help you.

10. don't be afraid to experiment and try new things

I was a fanfiction writer for a long time and was so scared to try original fiction because it seemed so much different from what I was accustomed to doing. however, once I decided to try something new, I discovered I liked to do it more than fanfiction. you'll never know until you try it!

11. never give up on your writing, keep practicing and learning to improve your skills

it takes time to acquire new skills, so if you're new to writing, please don't give up! It's fun and a long path, and I promise you'll love it, even more, the more you write!

I hope this was helpful! <3 have a nice day

also, i just released a new freebie!!! it's a free workbook for writers with over 90 pages to guide you through the process of plotting a novel. you might be interested in checking it out!! :D click here

#wriblr#writeblr#writing inspiration#writing prompts#writing advice#writers#writing#writer tips#writerscommunity#writing help#writing resources#writing tips#writer problems#amateur writer#tips for writers#fiction novel#fiction tips#original fiction#original writing#author struggles#authors#author#writer#novelwriting#novelist#novosautores#escritores#novelista#fanfiction writer#writer's block

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The plain fact is that whatever Homer or Aeschylus might have had to say about the Persians or Asia, it simply is not a reflection of a ‘West’ or of ‘Europe’ as a civilizational entity, in a recognizably modern sense, and no modern discourse can be traced back to that origin, because the civilizational map and geographical imagination of Antiquity were fundamentally different from those that came to be fabricated in post-Renaissance Europe.

[...] It is also simply the case that the kind of essentializing procedure which Said associates exclusively with ‘the West’ is by no means a trait of the European alone; any number of Muslims routinely draw epistemological and ontological distinctions between East and West, the Islamicate and Christendom, and when Ayatollah Khomeini did it he hardly did so from an Orientalist position. And of course, it is common practice among many circles in India to posit Hindu spirituality against Western materialism, not to speak of Muslim barbarity. Nor is it possible to read the Mahabharata or the dharmshastras without being struck by the severity with which the dasyus and the shudras and the women are constantly being made into the dangerous, inferiorized Others. This is no mere polemical matter, either. What I am suggesting is that there have historically been all sorts of processes – connected with class and gender, ethnicity and religion, xenophobia and bigotry – which have unfortunately been at work in all human societies, both European and non-European. What gave European forms of these prejudices their special force in history, with devastating consequences for the actual lives of countless millions and expressed ideologically in full-blown Eurocentric racisms, was not some transhistorical process of ontological obsession and falsity – some gathering of unique force in domains of discourse – but, quite specifically, the power of colonial capitalism, which then gave rise to other sorts of powers. Within the realm of discourse over the past two hundred years, though, the relationship between the Brahminical and the Islamic high textualities, the Orientalist knowledges of these textualities, and their modern reproductions in Western as well as non-Western countries have produced such a wilderness of mirrors that we need the most incisive of operations, the most delicate of dialectics, to disaggregate these densities.

Aijaz Ahmed, In Theory: Nations, Literatures, Classes

632 notes

·

View notes

Note

imagine getting tickets for the renaissance tour with pedro and sarah and then reader (also an actress) finds out their pregnant, but of course that not stoping them. and reader went to the concert like 6 months pregnant and then news are reporting it, fan freaking out

sorry if that was a lot

(that wasn’t a lot don’t worry)

———————————————————————————

The tickets for the Renaissance tour dropped and you didn't even hesitate a second to buy them with Pedro. You were not going to miss that, nothing would make you miss going to see Beyoncé, your idol, on tour. If you didn't have a career you would have travelled to the integrity of the tour, but well, you couldn't. But one concert is good enough!

But something happened. Something that could change your future. Two months after buying your tickets for the concert, you fell ill. You got sick for a week. You kept waking up early with nausea, you kept throwing up. You were also very tired, you spent the afternoon on the couch napping. After three days of struggling, you decided to go to the doctor to get checked out.

After the appointment and the blood test, the results came back. You were pregnant. You've been with Pedro for 3 years now so it wasn't too soon on the relationship, but you didn't know if Pedro was ready, well, you didn't even know if you were ready at all. You didn't even wait at the end of the day to tell him. You couldn't handle this on your own, so you drove to his set and waited for him to take a break. Once the news were dropped, Pedro was actually happy about it. He never thought he would ever be a father, and this was the opportunity he was apparently waiting for. So you decided to keep the baby.

But as the months passed by, you realised that you were going to be deeply pregnant once the renaissance concert would arrive. You debated for days, even fought with Pedro because he didn't want you to come, to risk anything while you definitely wanted to go and risk everything. This was your dream, and it would, for sure, be a lot harder to go to a concert once the baby would be born.

So there you were, six months pregnant, walking in the stadium, holding hands with Pedro, Sarah and her friends behind you. Thank god you had a good spot in the front so that you could have some space. And it was the best night of your life. You never regretted once. Being pregnant didn't stop you from having fun. Your legs and back were hurting, but it wasn't that bad, it didn't bother you.

You were able to sing very loud, to dance a little, you laughed with your friends and boyfriend, you took some pictures and videos. But, being a famous actress, nothing stays unseen. Of course, people, fans noticed you were there. But they didn't only notice you, they noticed the huge bump you had. And they had a strong opinion about it. Most of the people were shocked that you were six months pregnant and went through hours of very loud music, standing and singing. It wasn't "healthy" for the baby.

You didn't think much of it when you saw that you were trending on socials because of that, until you were peacefully watching the news and saw your face appear on the screen. There was a polemic because you were six months pregnant and you went to a concert. You couldn't believe it. Your phone was blowing up, and your publicist was among it, trying to call you so that you could fix this mess.

That's how you found yourself making a video that you would publish on Instagram, Twitter, even TikTok in order to explain the situation. You found it very childish, Pedro thought the same thing. You weren't going to apologise, what for? But you still had to say something. It was about yourself after all.

"Hello everyone" you waved at the camera "I'm here, making this video because of something I'm not really sure I understand" you laughed awkwardly "but I think it was because I am currently six months pregnant and I went to a concert and you're not happy about it?" you pretended to think "I don't really have much to say, except that I talked about it with my doctor before, it wasn't something irrational that I just did like that." you started to explain "I made sure it was okay for the baby, and safe for me to go before actually going, I'm not crazy" you said at the camera "Also, I wasn't alone, my boyfriend was here, as well as our friends, so they took good care of me" you smiled, trying to sound serious and not sarcastic. "So, there is no need to make a polemic for this, to spread rumours and all. I am fine, the baby is great, everyone had a good time." you continued, touching your belly "I can also assure you that I will not go to an other concert, but not because you convinced me not to, but only because I will be working instead" you paused "I am pregnant, I am not sick, I can still do things" you shrugged "Anyway, thank you for worrying about me and the baby, but this is none of your business and we are well supported. Bye!" You blew a kiss at the camera of your phone before shutting it off.

Wow, what people can make you do, you thought. But you still sent the video away so that you could finally live peacefully, for a while at least, hoping the video would work. And it did work. Mostly. People apologised as they noticed they crossed a line. But of course there are still haters out there, thinking it was unforgivable. But whatever, a few less fans won't hurt. The good ones are still here supporting you.

#fanfic#oneshot#imagine#pedro pascal#pedro pascal fanfiction#pedro pascal x reader#pedro pascal imagine#pedro pascal x y/n#pedro pascal preferences#pedro pascal x you#pedro pascal one shot#pedro pascal x female reader#pedrostories#pedro pascal x pregnant!reader#pedro pascal x actress!reader

180 notes

·

View notes

Text

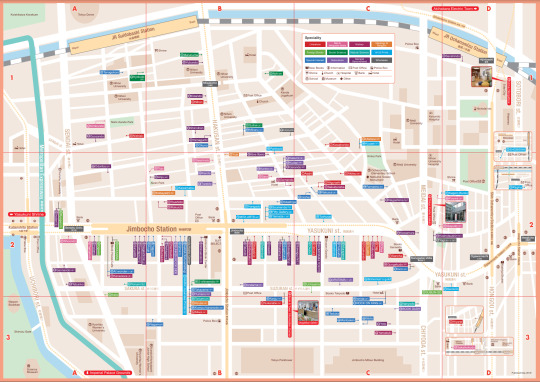

Another big stop in Tokyo for me was Jimbocho Book Town! It is a neighborhood of, depending on who you ask, up to 400 generally-secondhand bookstores flanked by some of the major universities in Tokyo. The local government even prints out maps of the stores to help people find them all:

Which, you will note, is not 400 stores, because the process of becoming an "official" Jimbocho Town Bookstore is an intensely political operation run by local stakeholders with tons of fights over what should qualify and what rights that entails - never change humanity!

"Book Towns" used to actually be quite a common thing, and they peaked during the literary boom of the late 19th century. Figuring out "what books existed" was a hard task, and to do serious research you needed to own the books (you weren't making photocopies), so concentrating specialty bookstores in one area made sense to allow someone to go to one place and ask around to find what they need and discover what exists. It was academia's version of Comiket! Modern digital information & distribution networks slowly killed or at least reduced these districts in places like Paris or London, but Jimbocho is one of the few that still survives.

Why it has is multi-causal for sure - half of this story is that Tokyo is YIMBY paradise and has constantly built new buildings to meet demand so rents have been kept down, allowing low-margin, individually-owned operations to continue where they have struggled in places like the US. These stores don't make much money but they don't have to. But as important is that Japan has a very strong 'book collector' culture, it's the original baseball cards for a lot of people. The "organic" demand for a 1960's shoujo magazine or porcelainware picture book is low, but hobbyists building collections is a whole new source of interest. Book-as-art-collection powered Jimbocho through until the 21st century, where - again like Comiket - the 'spectacle' could give it a lift and allow the area to become a tourist attraction and a mecca for the ~cozy book hoarder aesthetic~ to take over. Now it can exist on its vibes, which go so far as to be government-recognized: In 2001 the "scent wafting from the pages of the secondhand bookstore" was added to Japan's Ministry of Environment's List of 100 Fragrance Landscapes.

Of course this transition has changed what it sells; when it first began in the Meiji area, Jimbocho served the growing universities flanking it, and was a hotpot of academic (and political-polemic) texts. Those stores still exist, but as universities built libraries and then digital collections, the hobby world has taken over. Which comes back to me, baby! If you want Old Anime Books Jimbocho is one of the best places to go - the list of "subculture" stores is expansive.

I'll highlight two here: the first store I went to was Kudan Shobo, a 3rd floor walk-up specializing in shoujo manga. And my guys, the ~vibes~ of this store. It has this little sign outside pointing you up the stairs with the cutest book angel logo:

And the stairs:

Real flex of Japan's low crime status btw. Inside is jam-packed shelves and the owner just sitting there eating dinner, so I didn't take any photos inside, but not only did it have a great collection of fully-complete shoujo magazines going back to the 1970's, it had a ton of "meta" books on shoujo & anime, even a doujinshi collection focusing on 'commentary on the otaku scene' style publications. Every Jimbocho store just has their own unique collection, and you can only discover it by visiting. I picked up two books here (will showcase some of the buys in another post).

The other great ~subculture~ store I went to was Yumeno Shoten - and this is the store I would recommend to any otaku visiting, it was a much broader collection while still having a ton of niche stuff. The vibes continued to be immaculate of course:

And they covered every category you could imagine - Newtype-style news magazine, anime cels, artbooks, off-beat serial manga magazines, 1st edition prints, just everything. They had promotional posters from Mushi Pro-era productions like Cleopatra, nothing was out of reach. I got a ton of books here - it was one of the first stores I visited on my second day in Jimobocho, which made me *heavily* weighed down for the subsequent explorations, a rookie mistake for sure. There are adorable book-themed hotels and hostels in Jimbocho, and I absolutely could see a trip where you just shop here for a week and stay nearby so you can drop off your haul as you go.

We went to other great stores - I was on the lookout for some 90's era photography stuff, particularly by youth punk photographer Hiromix (#FLCL database), and I got very close at fashion/photography store Komiyama Shoten but never quite got what I was looking for. Shinsendo Shoten is a bookstore devoted entirely to the "railway and industrial history of Japan" and an extensive map collection, it was my kind of fetish art. My partner @darktypedreams found two old copies of the fashion magazine Gothic & Lolita Bible, uh, somewhere, we checked like five places and I don't remember which finally had it! And we also visited Aratama Shoten, a store collecting vintage pornography with a gigantic section on old BDSM works that was very much up her alley. It had the porn price premium so we didn't buy anything, but it was delightful to look through works on bondage and non-con from as far back as the 1960's, where honestly the line between "this is just for the fetish" and "this is authentic gender politics" was...sometimes very blurry. No photos of this one for very obvious reasons.

Jimbocho absolutely earned its rep, its an extremely stellar example of how history, culture, and uh land use policy can build something in one place that seems impossible in another operating under a different set of those forces. Definitely one of the highlights of the trip.

290 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Don’t mention the word ‘liberalism,’ ” the talk-show host says to the guy who’s written a book on it. “Liberalism,” he explains, might mean Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama to his suspicious audience, alienating more people than it invites. Talk instead about “liberal democracy,” a more expansive term that includes John McCain and Ronald Reagan. When you cross the border to Canada, you are allowed to say “liberalism” but are asked never to praise “liberals,” since that means implicitly endorsing the ruling Trudeau government and the long-dominant Liberal Party. In England, you are warned off both words, since “liberals” suggests the membership of a quaintly failed political party and “liberalism” its dated program. In France, of course, the vagaries of language have made “liberalism” mean free-market fervor, doomed from the start in that country, while what we call liberalism is more hygienically referred to as “republicanism.” Say that.

Liberalism is, truly, the love that dare not speak its name. Liberal thinkers hardly improve matters, since the first thing they will say is that the thing called “liberalism” is not actually a thing. This discouraging reflection is, to be sure, usually followed by an explanation: liberalism is a practice, a set of institutions, a tradition, a temperament, even. A clear contrast can be made with its ideological competitors: both Marxism and Catholicism, for instance, have more or less explicable rules—call them, nonpejoratively, dogmas. You can’t really be a Marxist without believing that a revolution against the existing capitalist order would be a good thing, and that parliamentary government is something of a bourgeois trick played on the working class. You can’t really be a Catholic without believing that a crisis point in cosmic history came two millennia ago in the Middle East, when a dissident rabbi was crucified and mysteriously revived. You can push either of these beliefs to the edge of metaphor—maybe the rabbi was only believed to be resurrected, and the inner experience of that epiphany is what counts; maybe the revolution will take place peacefully within a parliament and without Molotov cocktails—but you can’t really discard them. Liberalism, on the other hand, can include both faith in free markets and skepticism of free markets, an embrace of social democracy and a rejection of its statism. Its greatest figure, the nineteenth-century British philosopher and parliamentarian John Stuart Mill, was a socialist but also the author of “On Liberty,” which is (to the leftist imagination, at least) a suspiciously libertarian manifesto.

Whatever liberalism is, we’re regularly assured that it’s dying—in need of those shock paddles they regularly take out in TV medical dramas. (“C’mon! Breathe, damn it! Breathe! ”) As on television, this is not guaranteed to work. (“We’ve lost him, Holly. Damn it, we’ve lost him.”) Later this year, a certain demagogue who hates all these terms—liberals, liberalism, liberal democracy—might be lifted to power again. So what is to be done? New books on the liberal crisis tend to divide into three kinds: the professional, the professorial, and the polemical—books by those with practical experience; books by academics, outlining, sometimes in dreamily abstract form, a reformed liberal democracy; and then a few wishing the whole damn thing over, and well rid of it.

The professional books tend to come from people whose lives have been spent as pundits and as advisers to politicians. Robert Kagan, a Brookings fellow and a former State Department maven who has made the brave journey from neoconservatism to resolute anti-Trumpism, has a new book on the subject, “Rebellion: How Antiliberalism Is Tearing America Apart—Again” (Knopf). Kagan’s is a particular type of book—I have written one myself—that makes the case for liberalism mostly to other liberals, by trying to remind readers of what they have and what they stand to lose. For Kagan, that “again” in the title is the crucial word; instead of seeing Trumpism as a new danger, he recapitulates the long history of anti-liberalism in the U.S., characterizing the current crisis as an especially foul wave rising from otherwise predictable currents. Since the founding of the secular-liberal Republic—secular at least in declining to pick one faith over another as official, liberal at least in its faith in individualism—anti-liberal elements have been at war with it. Kagan details, mordantly, the anti-liberalism that emerged during and after the Civil War, a strain that, just as much as today’s version, insisted on a “Christian commonwealth” founded essentially on wounded white working-class pride.

The relevance of such books may be manifest, but their contemplative depth is, of necessity, limited. Not to worry. Two welcomely ambitious and professorial books are joining them: “Liberalism as a Way of Life” (Princeton), by Alexandre Lefebvre, who teaches politics and philosophy at the University of Sydney, and “Free and Equal: A Manifesto for a Just Society” (Knopf), by Daniel Chandler, an economist and a philosopher at the London School of Economics.

The two take slightly different tacks. Chandler emphasizes programs of reform, and toys with the many bells and whistles on the liberal busy box: he’s inclined to try more random advancements, like elevating ordinary people into temporary power, on an Athenian model that’s now restricted to jury service. But, on the whole, his is a sanely conventional vision of a state reformed in the direction of ever greater fairness and equity, one able to curb the excesses of capitalism and to accommodate the demands of diversity.

The program that Chandler recommends to save liberalism essentially represents the politics of the leftier edge of the British Labour Party—which historically has been unpopular with the very people he wants to appeal to, gaining power only after exhaustion with Tory governments. In the classic Fabian manner, though, Chandler tends to breeze past some formidable practical problems. While advocating for more aggressive government intervention in the market, he admits equably that there may be problems with state ownership of industry and infrastructure. Yet the problem with state ownership is not a theoretical one: Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister because of the widely felt failures of state ownership in the nineteen-seventies. The overreaction to those failures may have been destructive, but it was certainly democratic, and Tony Blair’s much criticized temporizing began in this recognition. Chandler is essentially arguing for an updated version of the social-democratic status quo—no bad place to be but not exactly a new place, either.

Lefebvre, on the other hand, wants to write about liberalism chiefly as a cultural phenomenon—as the water we swim in without knowing that it’s wet—and his book is packed, in the tradition of William James, with racy anecdotes and pop-culture references. He finds more truths about contemporary liberals in the earnest figures of the comedy series “Parks and Recreation” than in the words of any professional pundit. A lot of this is fun, and none of it is frivolous.

Yet, given that we may be months away from the greatest crisis the liberal state has known since the Civil War, both books seem curiously calm. Lefebvre suggests that liberalism may be passing away, but he doesn’t seem especially perturbed by the prospect, and at his book’s climax he recommends a permanent stance of “reflective equilibrium” as an antidote to all anxiety, a stance that seems not unlike Richard Rorty’s idea of irony—cultivating an ability both to hold to a position and to recognize its provisionality. “Reflective equilibrium trains us to see weakness and difference in ourselves,” Lefebvre writes, and to see “how singular each of us is in that any equilibrium we reach will be specific to us as individuals and our constellation of considered judgments.” However excellent as a spiritual exercise, a posture of reflective equilibrium seems scarcely more likely to get us through 2024 than smoking weed all day, though that, too, can certainly be calming in a crisis.

Both professors, significantly, are passionate evangelists for the great American philosopher John Rawls, and both books use Rawls as their fount of wisdom about the ideal liberal arrangement. Indeed, the dust-jacket sell line of Chandler’s book is a distillation of Rawls: “Imagine: You are designing a society, but you don’t know who you’ll be within it—rich or poor, man or woman, gay or straight. What would you want that society to look like?” Lefebvre’s “reflective equilibrium” is borrowed from Rawls, too. Rawls’s classic “A Theory of Justice” (1971) was a theory about fairness, which revolved around the “liberty principle” (you’re entitled to the basic liberties you’d get from a scheme in which everyone got those same liberties) and the “difference principle” (any inequalities must benefit the worst off). The emphasis on “justice as fairness” presses both professors to stress equality; it’s not “A Theory of Liberty,” after all. “Free and equal” is not the same as “free and fair,” and the difference is where most of the arguing happens among people committed to a liberal society.

Indeed, readers may feel that the work of reconciling Rawls’s very abstract consideration of ideal justice and community with actual experience is more daunting than these books, written by professional philosophers who swim in this water, make it out to be. A confidence that our problems can be managed with the right adjustments to the right model helps explain why the tone of both books—richly erudite and thoughtful—is, for all their implication of crisis, so contemplative and even-humored. No doubt it is a good idea to tell people to keep cool in a fire, but that does not make the fire cooler.

Rawls devised one of the most powerful of all thought experiments: the idea of the “veil of ignorance,” behind which we must imagine the society we would want to live in without knowing which role in that society’s hierarchy we would occupy. Simple as it is, it has ever-arresting force, making it clear that, behind this veil, rational and self-interested people would never design a society like that of, say, the slave states of the American South, given that, dropped into it at random, they could very well be enslaved. It also suggests that Norway might be a fairly just place, because a person would almost certainly land in a comfortable and secure middle-class life, however boringly Norwegian.

Still, thought experiments may not translate well to the real world. Einstein’s similarly epoch-altering account of what it would be like to travel on a beam of light, and how it would affect the hands on one’s watch, is profound for what it reveals about the nature of time. Yet it isn’t much of a guide to setting the timer on the coffeemaker in the kitchen so that the pot will fill in time for breakfast. Actual politics is much more like setting the timer on the coffeemaker than like riding on a beam of light. Breakfast is part of the cosmos, but studying the cosmos won’t cook breakfast. It’s telling that in neither of these Rawlsian books is there any real study of the life and the working method of an actual, functioning liberal politician. No F.D.R. or Clement Attlee, Pierre Mendès France or François Mitterrand (a socialist who was such a master of coalition politics that he effectively killed off the French Communist Party). Not to mention Tony Blair or Joe Biden or Barack Obama. Biden’s name appears once in Chandler’s index; Obama’s, though he gets a passing mention, not at all.

The reason is that theirs are not ideal stories about the unimpeded pursuit of freedom and fairness but necessarily contingent tales of adjustments and amendments—compromised stories, in every sense. Both philosophers would, I think, accept this truth in principle, yet neither is drawn to it from the heart. Still, this is how the good work of governing gets done, by those who accept the weight of the world as they act to lighten it. Obama’s history—including the feints back and forth on national health insurance, which ended, amid all the compromises, with the closest thing America has had to a just health-care system—is uninspiring to the idealizing mind. But these compromises were not a result of neglecting to analyze the idea of justice adequately; they were the result of the pluralism of an open society marked by disagreement on fundamental values. The troubles of current American politics do not arise from a failure on the part of people in Ohio to have read Rawls; they are the consequence of the truth that, even if everybody in Ohio read Rawls, not everybody would agree with him.

Ideals can shape the real world. In some ultimate sense, Biden, like F.D.R. before him, has tried to build the sort of society we might design from behind the veil of ignorance—but, also like F.D.R., he has had to do so empirically, and often through tactics overloaded with contradictions. If your thought experiment is premised on a group of free and equal planners, it may not tell you what you need to know about a society marred by entrenched hierarchies. Ask Biden if he wants a free and fair society and he would say that he does. But Thatcher would have said so, too, and just as passionately. Oscillation of power and points of view within that common framework are what makes liberal democracies liberal. It has less to do with the ideally just plan than with the guarantee of the right to talk back to the planner. That is the great breakthrough in human affairs, as much as the far older search for social justice. Plato’s rulers wanted social justice, of a kind; what they didn’t want was back talk.

Both philosophers also seem to accept, at least by implication, the familiar idea that there is a natural tension between two aspects of the liberal project. One is the desire for social justice, the other the practice of individual freedom. Wanting to speak our minds is very different from wanting to feed our neighbors. An egalitarian society might seem inherently limited in liberty, while one that emphasizes individual rights might seem limited in its capacity for social fairness.

Yet the evidence suggests the opposite. Show me a society in which people are able to curse the king and I will show you a society more broadly equal than the one next door, if only because the ability to curse the king will make the king more likely to spread the royal wealth, for fear of the cursing. The rights of sexual minorities are uniquely protected in Western liberal democracies, but this gain in social equality is the result of a history of protected expression that allowed gay experience to be articulated and “normalized,” in high and popular culture. We want to live on common streets, not in fortified castles. It isn’t a paradox that John Stuart Mill and his partner, Harriet Taylor, threw themselves into both “On Liberty,” a testament to individual freedom, and “The Subjection of Women,” a program for social justice and mass emancipation through group action. The habit of seeking happiness for one through the fulfillment of many others was part of the habit of their liberalism. Mill wanted to be happy, and he couldn’t be if Taylor wasn’t.

Liberals are at a disadvantage when it comes to authoritarians, because liberals are committed to procedures and institutions, and persist in that commitment even when those things falter and let them down. The asymmetry between the Trumpite assault on the judiciary and Biden’s reluctance even to consider enlarging the Supreme Court is typical. Trumpites can and will say anything on earth about judges; liberals are far more reticent, since they don’t want to undermine the institutions that give reality to their ideals.

Where Kagan, Lefebvre, and Chandler are all more or less sympathetic to the liberal “project,” the British political philosopher John Gray deplores it, and his recent book, “The New Leviathans: Thoughts After Liberalism” (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), is one long complaint. Gray is one of those leftists so repelled by the follies of the progressive party of the moment—to borrow a phrase of Orwell’s about Jonathan Swift—that, in a familiar horseshoe pattern, he has become hard to distinguish from a reactionary. He insists that liberalism is a product of Christianity (being in thrall to the notion of the world’s perfectibility) and that it has culminated in what he calls “hyper-liberalism,” which would emancipate individuals from history and historically shaped identities. Gray hates all things “woke”—a word that he seems to know secondhand from news reports about American universities. If “woke” points to anything except the rage of those who use it, however, it is a discourse directed against liberalism—Ibram X. Kendi is no ally of Bayard Rustin, nor Judith Butler of John Stuart Mill. So it is hard to see it as an expression of the same trends, any more than Trump is a product of Burke’s conservative philosophy, despite strenuous efforts on the progressive side to make it seem so.

Gray’s views are learned, and his targets are many and often deserved: he has sharp things to say about how certain left liberals have reclaimed the Nazi jurist Carl Schmitt and his thesis that politics is a battle to the death between friends and foes. In the end, Gray turns to Dostoyevsky’s warning that (as Gray reads him) “the logic of limitless freedom is unlimited despotism.” Hyper-liberals, Gray tells us, think that we can compete with the authority of God, and what they leave behind is wild disorder and crazed egotism.

As for Dostoyevsky’s positive doctrines—authoritarian and mystical in nature—Gray waves them away as being “of no interest.” But they are of interest, exactly because they raise the central pragmatic issue: If you believe all this about liberal modernity, what do you propose to do about it? Given that the announced alternatives are obviously worse or just crazy (as is the idea of a Christian commonwealth, something that could be achieved only by a degree of social coercion that makes the worst of “woke” culture look benign), perhaps the evil might better be ameliorated than abolished.

Between authority and anarchy lies argument. The trick is not to have unified societies that “share values”—those societies have never existed or have existed only at the edge of a headsman’s axe—but to have societies that can get along nonviolently without shared values, aside from the shared value of trying to settle disputes nonviolently. Certainly, Americans were far more polarized in the nineteen-sixties than they are today—many favored permanent apartheid (“Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever”)—and what happened was not that values changed on their own but that a form of rights-based liberalism of protest and free speech convinced just enough people that the old order wouldn’t work and that it wasn’t worth fighting for a clearly lost cause.

What’s curious about anti-liberal critics such as Gray is their evident belief that, after the institutions and the practices on which their working lives and welfare depend are destroyed, the features of the liberal state they like will somehow survive. After liberalism is over, the neat bits will be easily reassembled, and the nasty bits will be gone. Gray can revile what he perceives to be a ruling élite and call to burn it all down, and nothing impedes the dissemination of his views. Without the institutions and the practices that he despises, fear would prevent oppositional books from being published. Try publishing an anti-Communist book in China or a critique of theocracy in Iran. Liberal institutions are the reason that he is allowed to publish his views and to have the career that he and all the other authors here rightly have. Liberal values and practices allow their most fervent critics a livelihood and a life—which they believe will somehow magically be reconstituted “after liberalism.” They won’t be.

The vociferous critics of liberalism are like passengers on the Titanic who root for the iceberg. After all, an iceberg is thrilling, and anyway the White Star Line has classes, and the music the band plays is second-rate, and why is the food French instead of honestly English? “Just as I told you, the age of the steamship is over!” they cry as the water slips over their shoes. They imagine that another boat will miraculously appear—where all will be in first class, the food will be authentic, and the band will perform only Mozart or Motown, depending on your wishes. Meanwhile, the ship goes down. At least the band will be playing “Nearer, My God, to Thee,” which they will take as some vindication. The rest of us may drown.

One turns back to Helena Rosenblatt’s 2018 book, “The Lost History of Liberalism,” which makes the case that liberalism is not a recent ideology but an age-old series of intuitions about existence. When the book appeared, it may have seemed unduly overgeneralized—depicting liberalism as a humane generosity that flared up at moments and then died down again. But, as the world picture darkens, her dark picture illuminates. There surely are a set of identifiable values that connect men and women of different times along a single golden thread: an aversion to fanaticism, a will toward the coexistence of different kinds and creeds, a readiness for reform, a belief in the public criticism of power without penalty, and perhaps, above all, a knowledge that institutions of civic peace are much harder to build than to destroy, being immeasurably more fragile than their complacent inheritors imagine. These values will persist no matter how evil the moment may become, and by whatever name we choose to whisper in the dark.

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mai, Satono and their peers: a look into the world of dōji

Okay, look, I get it, Mai and Satono are not the most thrilling characters. I suspect they would be at the very bottom of the list of stage 5 bosses people would like to see expanded upon. Perhaps they are not the optimal pick for another research deep dive. However, I would nonetheless like to try to convince you they should not be ignored altogether. If you are not convinced, this article has it all: esoteric Buddhism, accusations of heresy, liver eating, and even alleged innuendos.

As a bonus, I will also discuss a few other famous Buddhist attendant deities more or less directly tied to Touhou. Among other things, you will learn which figure technically tied to the plot of UFO is missing from its cast and what a controversial claim about a certain deity being a teenage form of Amaterasu has to do with Akyuu.

Mai, Satono and the grand Matarajin callout of 1698

An Edo period depiction of Matarajin and his attendants (via Bernard Faure's Protectors and Predators; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

As indicated both by their family names and their designs, Mai and Satono are based on Nishita Dōji (爾子多童子) and Chōreita Dōji (丁令多童子), respectively. These two deities are commonly depicted alongside Matarajin, acting as his attendants, or dōji. Nishita is depicted holding bamboo leaves and dancing, while Chōreita - playing a drum and holding ginger leaves. ZUN kept the plant attributes, though he clearly passed on the drum. In the HSiFS interview in SCoOW he said he initially wanted both of them to hold both types of leaves at once, so I presume that’s when the decision to skip the instrument has originally been made.

We do not actually fully know how Nishita and Chōreita initially developed. It is possible that their emergence was a part of a broader process of overhauling Matarajin’s iconography. While initially imagined as a fearsome multi-armed and multi-headed wrathful deity, with time he took the form of an old man dressed like a noble and came to be associated with fate and performing arts. The conventional depictions, with the attendants dancing while Matarajin plays a drum under the Big Dipper, neatly convey both of these roles. The group was additionally responsible for revealing the three paths (defilements, karma, and suffering) and three poisons (greed, hatred, and desire) to devotees.

In addition to being a mainstay of Matarajin’s iconography, Ninshita and Chōreita also had a role to play in a special ceremony focused on their master, genshi kimyōdan (玄旨帰命壇). This term is derived from the names of two separate Tendai initiation rituals, genshidan (玄旨壇) and kimyōdan (帰命壇).

Genshi kimyōdan can actually be considered the reason why Matarajin is relatively obscure today. In 1698, the rites were outlawed during a campaign meant to reform the Tendai school. It was lead by the monk Reiku (霊空), who compiled his opinions about various rituals in Hekijahen (闢邪篇, loosely “Repudiation of Heresies”). Matarajin is not directly mentioned there, and the polemic with genshi kimyōdan is instead focused on a set of thirteen kōan pertaining to it, with mistakes pointed out for each of them. Evidently this was pretty successful at curbing his prominence anyway, though.

By the 1720s, even members of Tendai clergy could be somewhat puzzled after stumbling upon references to Matarajin, and in a text from 1782 we can read that he was a “false icon created by the stupidest of stupid folks“. He ceased to be venerated on Mount Hiei, the center of the Tendai tradition, though he did not fade away entirely thanks to various more peripheral temples, for example in Hiraizumi in the north. Ironically, this decline is very likely why Matarajin survived the period of shinbutsu bunri policies largely unscathed when compared to some of his peers like Gozu Tennō.

“Nine out of ten Shingon masters believe this”, or the background of the Matarajin callout

Dakiniten (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Tendai reformers and critics associated genshi kimyōdan with an (in)famous Shingon current supposedly linked with Dakiniten, Tachikawa-ryū. This is a complex issue in itself, and would frankly warrant a lengthy essay itself if I wanted to do it justice; the most prominent researcher focused on it, Nobumi Iyanaga, said himself that “it is challenging to write about the Tachikawa-ryū in brief, because almost all of what has ever been written on this topic is based on a preconceived image and is in need of profound revision”. I will nonetheless try to give you a crash course.

Recent reexaminations indicate that originally Tachikawa-ryū might have been simply a combination of Shingon with Onmyōdō and local practices typical for - at the time deeply peripheral - Musashi Province. Essentially, it was an ultimately unremarkable minor lineage extant in the 12th and 13th centuries. A likely contemporary treatise, Haja Kenshō Shū (破邪顕正集; “Collection for Refuting the Perverse and Manifesting the Correct”) indicates it was met with at best mixed reception among religious elites elsewhere, but that probably boils down to its peripheral character.

Starting with Yūkai (宥快; 1345–1416) Shingon authors, and later others as well, came to employ Tachikawa-ryū as a boogeyman in doctrinal arguments, though. Anything “heretical” (or anything a given author had a personal beef with) could be Tachikawa-ryū, essentially. It was particularly often treated as interchangeable with a set of deeply enigmatic scrolls, referred to simply as “this teaching, that teaching” (kono hō, kano hō, 此の法, 彼の法; I am not making this up, I am quoting Iyanaga); I will refer to it as TTTT through the rest of the article.

These two were mixed up because of the monk Shinjō (心定; 1215-1272) who expressed suspicion about TTTT because of its alleged popularity in the countryside, where “nine out of ten Shingon masters” believe it to be the most genuine form of esoteric Buddhism. However, he stresses TTTT was not only non-Buddhist, but in fact demonic. The description of this so-called “abominable skull honzon”, “skull ritual” or, to stick to the original wording, “a certain ritual” (彼ノ法, ka no hō) meant to prove the accusations is, to put it lightly, quite something.

Essentially, the male practitioner of TTTT has to have sex with a woman, then smear a skull with bodily fluids generated this way over and over again, and finally keep it in warmth for seven years so that it can acquire prophetic powers. This works because dakinis (a class of demons) live inside the skull. The entire process takes eight years because Dakiniten, the #1 dakini, attained enlightenment at the age of 8.

Shinjō himself did not assert TTTT was identical with Tachikawa-ryū, though - he merely claimed that at one point he found a bag of texts which contained sources pertaining to both of them.

Ultimately it’s not even certain if TTTT is real. It might be an entirely literary creation, or an embellishment of some genuine tradition circulating around some marginal group like traveling ascetics. We will likely never know for sure.

Regardless of that, Tachikawa-ryū became synonymous not just with incorrect teachings, but specifically with teachings with inappropriate sexual elements. By extension, it was alleged that the songs and dances associated with Matarajin and his two servants performed during genshi kimyōdan similarly had inappropriate sexual undertones.

ZUN seems to be aware of these implications, since the topic came up in the aforementioned interview. The interviewer states they read that “during the middle ages a lot of Tendai and Shingon sects end up becoming obsessed with sexual rituals and wicked teachings, leading to their downfall” (bit of an overstatement). In response, ZUN explains that these matters are “interesting” and adds that he “did prepare some materials with that, but that would make [the game] too vulgar.” No dialogue or spell card in the game actually references genshi kimyōdan, for what it’s worth, but seeing as this is the only real point of connection between Matarajin and such accusations it’s safe to say ZUN is to some degree familiar with the discussed matter.

As in the case of the Tachikawa-ryū, modern researchers are often skeptical if there really was a sexual, orgiastic component to the rituals, though. A major problem with proper evaluation is that very few actual primary sources survive. We know the words of the songs associated with Matarajin’s dōji, but they are not very helpful. They’re borderline gibberish, “shishirishi ni shishiri” alternating with “sosoroso ni sosoro”. Polemics present them either as an allusion to sex or as an invitation to it; as cryptic references to genitals; or as sounds of pleasure.

None of these claims find any support in the few surviving primary sources, though. Earlier texts indicate that the dance and song of the dōji was understood as a representation of endless transmigration during the cycle of samsara. When sex does come up in related sources, it is presented negatively, in association with ignorance. Bernard Faure argues that the rituals were initially apotropaic, much like the tengu odoshi (天狗怖し), which I plan to cover next month since it helps a lot with understanding what’s going on in HSiFS. The goal was seemingly to guarantee Matarajin will help the faithful be reborn in the pure land of Amida. However, the method he was believed to utilize to that end can be at best described as unconventional.

To unburden the soul from bad karma, Matarajin had to devour the liver of a dying person. This is essentially a positive twist on a habit attributed in Buddhism to certain classes of demons, especially dakinis, said to hunger for so-called “human yellow” (人黄, ninnō), to be understood as something like vital essence, or for specific body parts. In this highly esoteric context, Matarajin was at once himself a sort of dakini, and a tamer of them (usually the role of Mahakala), and thus capable of utilizing their normally dreadful behavior to positive ends.

The true understanding of these actions was knowledge apparently reserved for a small audience, though. Keiran shūyōshū (溪嵐拾葉集), a medieval compendium of orally transmitted Tendai knowledge, asserts that even monks actively involved in the worship of Matarajin were unfamiliar with it.

Beyond Mai and Satono: dōji as a class of deities

You might be wondering why an article which was supposed to be an explanation of Mai and Satono ended up spending so much time on ambivalent aspects of Matarajin’s character instead. The ambivalence present in the aforementioned liver-related belief was a fundamental component of the character of many deities once popular in esoteric Buddhism, and by extension of their attendants too. Therefore, it is actually key to understanding dōji.

As I already mentioned in my Shuten Dōji article a few weeks ago, when treated as a type of supernatural beings, the term dōji implies a degree of ambiguity. The youthfulness of these “lads” means that in most cases they were portrayed as unpredictable, impulsive, eager to subvert social order and hierarchies of power, and prone to hubris. Some of them are outright demonic figures, as already discussed last month. Simply put, they possess the stereotypical traits of a young person from the perspective of someone old. They initially seemingly developed as a Buddhist reflection of Taoist tongzi, in this context a symbol of immortality and youthfulness, though a case can be made that youthful Hindu deities like Skanda (Idaten) also had an influence on this process.

Many Buddhist deities can be accompanied by pairs or groups of dōji, for example Jizō, Kannon, Fudō, Dakiniten or Sendan Kendatsuba-ō. In some cases, other deities could manifest in the form of dōji. In Chiba there is a statue of Myōken reflecting such a tradition, for example. There are also “independent” dōji. Closely related terms include ōji (王子), “prince”, used to refer for example to the sons of Gozu Tennō and the attendants of Iizuna Gongen, and wakamiya (若宮), “young prince”, which typially designates the youthful manifestation of a local deity.In the second half of the article, I’ll describe some notable dōji who can be considered relevant to Touhou in some capacity.

Gohō dōji: the generic dōji and the legend of Myōren

A gohō dōji in the Shigisan Engi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

The term gohō dōji (護法童子) can be translated as something like “dharma-protecting lad”. It’s not the name of a specific dōji, but rather a subcategory of them. Historically they were understood as something like the Buddhist analog of shikigami. The term gohō itself has a broader meaning, and can refer to virtually any protective Buddhist deity, even wisdom kings or the four heavenly kings. The archetypal example of such a figure is Kongōshu (Vajrapāṇi), who according to Buddhist tradition acts as a protector of the historical Buddha.

A good example of a Gohō Dōji is Oto Gohō (乙護法) from Mount Sefuri. He reportedly appeared before the priest Shōkū (性空; 910–1007) before his journey to China, and protected him through its entire duration. Afterwards a temple was built for him. Curiously, this legend actually finds a close parallel in these pertaining to Matarajin, Sekizan Myōjin or Shinra Myōjin protecting monks traveling to China - except the deity involved is a youth rather than an old man.

From a Touhou point of view, the most important example of a gohō dōji is arguably this nameless one, though. He appears in the Shigisan Engi Emaki, an account of the miraculous deeds of the monk Myōren, who you doubtlessly know from UFO. The section focused on him is fairly straightforward: a messenger from the imperial court approaches Myōren because the emperor is sick. Using his supernatural powers, he summons a deity clad in a cape made out of swords to heal him without having to leave his dwelling on Mount Shigi himself. He obviously succeeds. Afterwards the court sends a messenger to offer Myōren various rewards, but he rejects them. While the emperor is not directly shown or named, he is presumably to be identified as Daigo.

While the supernatural helper is left unnamed and is often simply described as a gohō dōji in scholarship, it has been pointed out that his unusual iconography seems to be a variant of that associated with the fifth of the twenty eight messengers of Bishamonten. A depiction of a similar figure is known for example from the Ninna-ji temple in Kyoto. This makes perfect sense, seeing as the connection between Myōren and this deity is well documented, and recurs through the legends presented in the Shigisan Engi Emaki. Needless to say, it is also the reason why Bishamonten by proxy plays a role in the plot of UFO. Given these fairly direct references, I am actually surprised no UFO character borrows any visual cues from the gohō dōji, seeing as the illustration is quite famous. It was even featured on a stamp at one point.

Zennishi Dōji (Princeton University Art Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Yoshiaki Shimizu has suggested that the connection between Myōren and his Gohō Dōji is meant to mirror that between Bishamonten and his son and primary attendant, Zennishi Dōji (善膩師童子), and highlight that the monk was an incarnation of the deity he worshiped. He also argued that Myōren’s nameless sister (not attested outside Shigisan Engi Emaki) - the character ZUN based Byakuren on - is meant to correspond to Bishamonten’s wife, Kisshōten/Kichijōten (presumably with spousal bond turned into a sibling one). I am not sure if this proposal found broader support, though - I’m personally skeptical.

Kongara Dōji (and Seitaka Dōji): almost Touhou

Fudō Myōō, as depicted by Kyōsai (via ukiyo-e.org; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Kongara Dōji (衿羯羅童子, from Sanskrit Kiṃkara) and Seitaka Dōji (制多迦童子, from Sanskrit Ceṭaka) are arguably uniquely important as far as the divine dōji go - a case can be made that they were the model for the other similar pairs. They are regarded as attendants of Fudō Myōō (Acala), one of the “wisdom kings”, a class of wrathful deities originally regarded as personifications and protectors of a specific mantra or dhāraṇī. In Japanese esoteric Buddhism, they are understood as manifestations of Buddhas responsible for subjugating beings who do not embrace Buddhist teachings.

Acting as Fudō‘s servants is the primary role of Kongara and Seitaka. As a matter of fact, both of their names are derived from Sanskrit terms referring to servitude. This is not reflected in their behavior fully: esoteric Buddhist sources indicate that Kongara is guaranteed to help a devotee who would implore him for help, but Seitaka is likely to disobey such a person. Interestingly, both can be recognized as manifestations of Fudō. This seems to reflect a broader pattern: once a deity ascended to a prominent position in esoteric Buddhism, some of their functions could be reassigned to members of their entourage. ZUN arguably references this in Mai and Satono’s bio, according to which “their abilities (...) are nothing more than an extension of Okina's.”

Despite the aforementioned shared aspect of their nature, Kongara and Seitaka actually have completely different iconographies. Kongara is portrayed with pale skin, wearing a monastic robe (kesa) and with his hands typically joined in a gesture of respect. Seitaka, meanwhile, has red skin, and holds a vajra in his left hand and a staff in the right. His characteristic five tufts of hair are a hairdo historically associated with people who were sentenced to banishment or enslavement. He’s never portrayed wearing a kesa in order to stress that in contrast with his “coworker” he possesses an evil nature. It has been argued the fundamental ambivalence of dōji is behind this difference in temperaments.

While the pair consisting of Kongara and Seitaka represents the most common version of Fudō’s entourage, he could also be portrayed alongside eight (a Chinese tradition) or uncommonly thirty six attendants. The core two are always present no matter how many extra dōji are present, though. Appearing together is essentially their core trait, and probably is part of the reason why they could be identified with other duos of supernatural servants, like En no Gyōja’s attendants Zenki and Gōki (who as you may know are referenced in Touhou in one of Ran’s PCB spell cards, and in a variety of print works).

As for the Touhou relevance of Kongara and Seitaka, a character very obviously named after the former appeared all the way back in Highly Responsive to Prayers, but I will admit I am personally skeptical if this can be considered an actual case of adaptation of a religious figure. There are no iconographic similarities between them, and their roles to put it lightly also don't seem particularly similar. Much like the PC-98 use of the term makai (which I will cover next month), it just seems like a random choice.

At least back in the day there was a fanon trend of treating the HRtP Konngara as an oni and a fourth deva of the mountain, but I will admit I never quite got that one. In contrast with Yuugi and Kasen’s counterparts, Kongara's namesake actually doesn’t have anything to do with Shuten Dōji.

The less said about a nonsensical comment on the wiki asserting Kongara’s status as a yaksha (something I have not seen referenced outside of Touhou headcanons, mostly from the reddit/tvtropes side of the fandom) explains why his supposed Touhou counterpart is present in hell, the better.

Uhō Dōji: my life as a teenage Amaterasu protector of gumonji practitioners

Uhō Dōji (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Uhō Dōji (雨宝童子), “rain treasure child”, will be the last dōji to be discussed here due to being by far the single most unusual member of this category. Following most authors, I described Uhō Dōji as a male figure through the article, but as noted by Anna Andreeva, most depictions are fairly androgynous. Bernard Faure points out sources which seem to refer to Uhō Dōji as female exist too; this is why I went with a gender neutral translation of dōji. In any case, the iconography is fairly consistent, as documented already in the Heian period: youthful face, long hair, wish-fulfilling jewel in one hand, decorated staff in the other, plus somewhat unconventional headwear, namely a five-wheeled stupa (gorintō).

Originally Uhō Dōji was simply a guardian deity of Mount Asama. He is closely associated with Kongōshō-ji, dedicated to the bodhisattva Kokūzō. The latter is locally depicted with Uhō Dōji and Myōjō Tenshi (明星天子), a personification of Venus, as his attendants.Originally the temple was associated with the Shingon school of Buddhism, though today it instead belongs to the Rinzai lineage of Zen.

A legend from the Muromachi period states that Kongōshō-ji was originally established in the sixth century, during the reign of emperor Kinmei by a monk named Kyōtai Shōnin (暁台上人).The latter initially created a place for himself to perform a ritual popularly known as gumonji (properly Gumonji-hō, 求聞持法, “inquiring and retaining [in one’s mind]”).The name Kongōshōji was only given to it later when Kūkai, the founder of the Shingon school of Buddhism (from whose traditions gumonji originates), received two visions - one from a dōji and then another from Amaterasu - that a place suitable to perform gumonji exists on Mount Asama. After arriving there, he stumbled upon the ruins of Kyōtai Shōnin’s temple, so he had it rebuilt and renamed it. Subsequently, Amaterasu appointed Uhō Dōji to the position of the protector of both this location and Buddhist devotees partaking in gumonji in general.

Most of you probably know that gumonji pops up in Touhou as the name of Akyuu’s ability in Perfect Memento in Strict Sense. ZUN describes it simply as perfect memory, but in reality it’s an esoteric religious practice focused on chanting the mantra of Kokūzō 1000000 times over the course of a set period of time (either 100 or 50 days). The goal is to develop perfect memory in order to be able to memorize all Shingon texts, though it is also believed to increase merit and grant prosperity in general. The oldest references to it come from the eighth century, and based on press coverage it is still performed today.

ZUN actually never mentioned gumonji in a context which would stress the term’s Buddhist character. In Forbidden Scrollery Akyuu prays to Iwanagahime rather than to any Buddhist figures. I get the idea behind that, but I will admit I liked the portrayal of her religious activities in Ashiyama’s Gensokyo of Humans much more.

Gumonji aside, the second major point of interest is the connection between Uhō Dōji and Amaterasu. In the legend I’ve summarized above, they are obviously two separate figures, with one taking a subordinate position. This changed later on, though. At some point, most likely between 1419 and 1428, the two deities came to be conflated. As Bernard Faure put it, Uhō Dōji effectively came to be seen as the “Buddhist version of Amaterasu”. To be specific, as Amaterasu at the age of sixteen, presumably to account for the fact that a dōji would by default be a youthful figure.

The treatise Uhō Dōji Keibyaku goes further and asserts that that Uhō Dōji manifests in India as the historical Buddha, Amida and Dainichi; in China as Fuxi, Shennong and Huang Di; and in Japan as Amaterasu, Tsukuyomi and Ninigi. In his astral role, he represents the planet Venus, but he can also manifest as Dakiniten and Benzaiten, in this context understood as respectively lunar and solar. He is also the creator of all of these astral bodies.

The grandiose claims about Uhō Dōji, Amaterasu and other major figures were not exactly uncontroversial. It seems that especially in the eighteenth century the Ise clergy objected to them, presumably because they effectively amounted to their peers at Kongōshō-ji promoting their own deity to make the temple more important as a part of the Ise pilgrimage, which at the time enjoyed considerable popularity.

The association between Amaterasu and Uhō Dōji nonetheless persisted through the Edo period, and despite protests voiced at Ise among laypeople Mount Asama was widely recognized as the third most important destination for participants in the Ise pilgrimage, next to the outer and inner shrines at Ise themselves. It is also quite likely that there was no shortage of people who would imagine Amaterasu looking just like Uhō Dōji.

Ultimately the Uhō Dōji controversy was just one of the many chapters in Amaterasu’s long and complex history, and there was nothing particularly unusual about the claims made. There were quite literally dozens of Buddhist or at least Buddhist-adjacent figures she developed connections to (Bonten, Enma and Mara, to name but a few), and the Ise clergy took active part in this process. Buddhist reinterpretations of Amaterasu flourished especially through the Japanese middle ages.

It was only the era of Meiji reforms that brought the end to this, cementing the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki inspired vision of Amaterasu as the only appropriate one. However, this is beyond the scope of this article. Worry not, though: the very next one I’m working on will cover these matters in detail. Please look forward to it.

Bibliography

Anna Andreeva, “To Overcome the Tyranny of Time”: Stars, Buddhas, and the Arts of Perfect Memory at Mt. Asama