#recovery from ME/CFS

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Just because you could doesn't mean you should

I think this is one of the biggest stumbling blocks of mild to moderate ME/CFS…just because you can do something doesn’t mean you should (and by the way, if you have severe ME/CFS the chances are you couldn’t even if you wanted to, which is the only reason I leave it out). Really, I suspect that this mindset of always doing as much as we are capable of is one of the commonest things to trip-up,…

#articles#guilted into overdoing it#invisible illness#long-covid#ME/CFS#ME/CFS functionality#ME/CFS setbacks#misunderstanding of ME/CFS#overdoing it#pacing#recovery from ME/CFS#shedding the mindset of ought#stabilising ME/CFS#the harmful mindset of productivity#why do I keep crashing#why do we push ourselves

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

When the Body Speaks: A Letter on ME/CFS and Forgiveness

Today, I felt it coming—a noxious wave rising from deep within. A bright, warning orange sliding straight into red, and before long, a full-blown crash. The heaviness in my limbs like wet sand, my mind fogged and thick. The weight of having done too much, more than my body could tolerate, more than it could carry. I knew this would happen. I overrode my limits packing, moving into a new…

#chronic fatigue coping strategies#chronic fatigue syndrome#chronic illness acceptance#chronic illness mental health#chronic illness self-care#coping with PEM#dealing with ME/CFS crashes#energy management chronic illness#Fatigue management#forgiving yourself with chronic illness#healing from PEM#health#Inner peace#living with chronic fatigue#managing fatigue#managing post-viral fatigue#ME/CFS#ME/CFS blog#ME/CFS flare-up#ME/CFS pacing techniques#ME/CFS support#meditation#mental-health#Mindfulness#Myalgic Encephalomyelitis#non-duality#overexertion recovery#pacing with ME/CFS#PEM crash recovery#post-exertional malaise

1 note

·

View note

Text

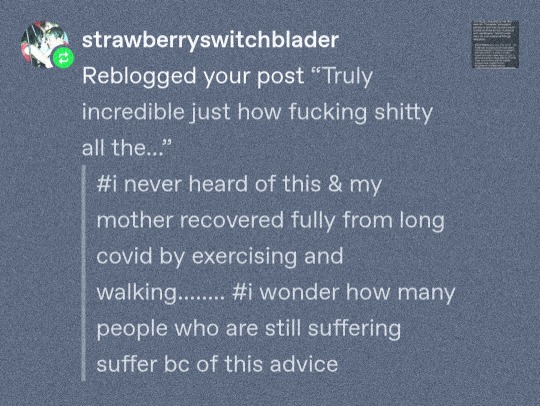

@strawberryswitchblader One of the problems surrounding Long Covid as a diagnosis is that it encompasses an overly broad variety of post-acute sequelae. You have people experiencing everything from scarring on the lungs, liver and kidney damage, to loss of smell. Then there are those who develop dysautonomic conditions like POTS or who are later diagnosed with ME/CFS and experience Post-Exertional Malaise. There is also a very large (perhaps even the majority) group of persons who will experience a prolonged but temporary period of post-viral fatigue; these are the people who recover gradually on their own, generally within a timeframe of six to eight months. It's not really exercise that leads to their recovery, they would have recovered on their own, and may even have recovered more quickly through a program of radical rest. My beautiful girlfriend is dealing with some post-viral fatigue right now after having gotten sick with mononucleosis this past summer. It's been a real struggle for her dealing with it, but she's also not experiencing PEM, so I'm confident she'll fully recover.

Many of the people who make claims about recovering from "chronic fatigue syndrome" through exercise therapy or some psychological treatment are in this post-viral fatigue category and mistaking correlation for causation and forgetting that the plural of anecdote is not data. The data overwhelmingly supports the notion that for patients experiencing PEM, graded exercise leads to a worsened disease state and a potentially permanently lowered baseline. Before I was diagnosed it's precisely how I inadvertently powerlifted, nightwalked and gradschooled myself into becoming housebound.

And having lived with ME at varying degrees of severity going on twenty-seven years now, I gotta say, it's very boring resting all the time. You get antsy fast. If all it took to get better was walking a bit more every day, I'd jump at the chance, but exercise doesn't really do much for chronic CD8+ T cell exhaustion, or hypofusion causing excess calcium and sodium buildup in skeletal muscles leading to mitochondrial damage. There was a paper that came out just a few months ago that published the results of analyzing blood samples from nearly 1500 ME/CFS patients and 130,000 healthy controls, and they discovered hundreds of biomarkers which indicated everything from insulin resistance to poor blood oxygenation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and systemic chronic inflammation. You can't fix any of that with exercise.

It's all a mess, there really needs to be stricter research diagnostic criteria, and better delineation between the various subtypes. It would clear up so much confusion, but that's also why there haven't been tighter criteria. Exercise and therapy makes for a very inexpensive treatment, one that insurance companies are far more willing to back than experimental anti-viral treatments or IVIg therapy, and in some countries the disability allowances for psychological conditions is less than for physical conditions. If you keep it ambiguous if Long Covid or ME/CFS or fibromyalgia or POTS are physical or psychological diseases, well you save austerity governments a few bucks there too.

#chronic illness#me/cfs#long covid#sorry for using your tags as a jumping off point for an essay. i'm glad your mom recovered.

625 notes

·

View notes

Text

also preserved on our archive

by Rowan Walrath

Public and private funding is lacking, scrambling opportunities to develop treatments

In brief Long COVID is a difficult therapeutic area to work in. It’s a scientifically challenging condition, but perhaps more critically, few want to fund new treatments. Private investors, Big Pharma, and government agencies alike see long COVID as too risky as long as its underlying mechanisms are so poorly understood. This dynamic has hampered the few biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies trying to develop new medicines. The lack of funding has frustrated people with long COVID, who have few options available to them. And crucially, it has snarled research and development, cutting drug development short.

When COVID-19 hit, the biotechnology company Aim ImmunoTech was developing a drug for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, better known as ME/CFS. As more people came down with COVID-19, some began to describe lingering problems that sounded a lot like ME/CFS. In many cases, people who got sick simply never seemed to get better. In others, they recovered completely—or thought they had—only to be waylaid by new problems: fatigue that wouldn’t go away with any amount of rest, brain fog that got in the way of normal conversations, a sudden tendency toward dizziness and fainting, or all the above.

There was a clear overlap between the condition, which patients began calling long COVID, and ME/CFS. People with ME/CFS have a deep, debilitating fatigue. They cannot tolerate much, if any, exercise; walking up a slight incline can mean days of recovery. Those with the most severe cases are bedbound.

Aim’s leaders set out to test whether the company’s drug, Ampligen, which is approved for ME/CFS in Argentina but not yet in the US, might be a good fit for treating long COVID. They started with a tiny study, just 4 people. When most of those participants responded well, they scaled up to 80. While initial data were mixed, people taking Ampligen were generally able to walk farther in a 6 min walk test than those who took a placebo, indicating improvement in baseline fatigue. The company is now making plans for a follow-on study in long COVID.

Aim’s motivation for testing Ampligen in long COVID was twofold. Executives believed they could help people with the condition, given the significant overlap in symptoms with ME/CFS. But they also, plainly, thought there’d be money. They were wrong.

“When we first went out to do this study in long COVID, there was money from . . . RECOVER,” Aim scientific officer Chris McAleer says, referring to Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery (RECOVER), the National Institutes of Health’s $1.7 billion initiative to fund projects investigating causes of, and potential treatments for, long COVID. McAleer says Aim attempted to get RECOVER funds, “believing that we had a therapeutic for these individuals, and we get nothing.”

Instead of funding novel medicines like Ampligen, the NIH has directed most of its RECOVER resources to observational studies designed to learn more about the condition, not treat it. Only last year did the agency begin to fund clinical trials for long COVID treatments, and those investigate the repurposing of approved drugs. What RECOVER is not doing is funding new compounds.

RECOVER is the only federal funding mechanism aimed at long COVID research. Other initiatives, like the $5 billion Project NextGen and the $577 million Antiviral Drug Discovery (AViDD) Centers for Pathogens of Pandemic Concern, put grant money toward next-generation vaccines, monoclonal antibodies, and antivirals for COVID-19. They stop short of testing those compounds as long COVID treatments.

Private funding is even harder to come by. Large pharmaceutical companies have mostly stayed away from the condition. (Some RECOVER trials are testing Pfizer’s COVID-19 antiviral Paxlovid, but a Pfizer spokesperson confirms that Pfizer is not sponsoring those studies.) Most investors have also avoided long COVID: a senior analyst on PitchBook’s biotech team, which tracks industry financing closely, says he isn’t aware of any investment in the space.

“What you need is innovation on this front that’s not driven by profit motive, but impact on global human health,” says Sumit Chanda, an immunologist and microbiologist at Scripps Research who coleads one of the AViDD centers. “We could have been filling in the gaps for things like long COVID, where pharma doesn’t see that there’s a billion-dollar market.”

The few biotech companies that are developing potential treatments for long COVID, including Aim, are usually funding those efforts out of their own balance sheets. Experts warn that such a pattern is not sustainable. At least four companies that were developing long COVID treatments have shut down because of an apparent lack of finances. Others are evaluating a shift away from long COVID.

“It is seen by the industry and by investors as a shot in the dark,” says Radu Pislariu, cofounder and CEO of Laurent Pharmaceuticals, a start-up that’s developing an antiviral and anti-inflammatory for long COVID. “What I know is that nobody wants to hear about COVID. When you say the name COVID, it’s bad . . ., but long COVID is not going anywhere, because COVID-19 is endemic. It will stay. At some point, everyone will realize that we have to do more for it.”

‘Time and patience and money’ Much of the hesitancy to make new medicines stems from the evasive nature of long COVID itself. The condition is multisystemic, affecting the brain, heart, endocrine network, immune system, reproductive organs, and gastrointestinal tract. While researchers are finding increasing evidence for some of the disease’s mechanisms, like viral persistence, immune dysregulation, and mitochondrial dysfunction, they might not uncover a one-size-fits-all treatment.

“Until we have a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms of long COVID, I think physicians are doing the best they can with the information they have and the guidance that is available to them,” says Ian Simon, director of the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Long COVID Research and Practice. The research taking place now will eventually guide new therapeutic development, he says.

Meanwhile, time marches on.

By the end of 2023, more than 409 million people worldwide had long COVID, according to a recent review coauthored by two cofounders of the Patient-Led Research Collaborative (PLRC) and several prominent long COVID researchers (Nat. Med. 2024; DOI: 10.1038/s41591-024-03173-6). Most of those 409 million contracted COVID-19 and then long COVID after vaccines and antivirals became available. That fact undercuts the notion that the condition results only from severe cases of COVID-19 contracted before those interventions existed. (Vaccination and treatment with antivirals do correlate with a lower incidence of long COVID but don’t prevent it outright.)

“There is that narrative that long COVID is over,” says Hannah Davis, cofounder of the PLRC and a coauthor of the review, who has had long COVID since 2020. “I think that’s fairly obviously not true.”

The few biotech companies that have taken matters into their own hands, like Aim, are often reduced to small study sizes with limited time frames because they can’t get outside funding.

InflammX Therapeutics, a Florida-based ophthalmology firm headed by former Bausch & Lomb executive Brian Levy, started testing an anti-inflammatory drug candidate called Xiflam after Levy’s daughter came down with long COVID. Xiflam is designed to close connexin 43 (Cx43) hemichannels when they become pathological. The hemichannels, which form in cell membranes, would otherwise allow intracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to escape and signal the NLRP3 inflammasome to crank up its activity, causing pain and inflammation.

InflammX originally conceived of Xiflam as a treatment for inflammation in various eye disorders, but after Levy familiarized himself with the literature on long COVID, he figured the compound might be useful for people like his daughter.

InflammX set up a small Phase 2a study at a site just outside Boston. The trial will enroll just 20 participants, including Levy’s daughter and InflammX’s chief operating and financial officer, David Pool, who also has long COVID. The study is set up such that participants don’t know if they’re taking Xiflam or a placebo.

Levy says the company tried to communicate with NIH RECOVER staff multiple times but never heard back. “We couldn’t wait,” he says.

Larger firms are similarly disconnected from US federal efforts. COVID-19 vaccine maker Moderna appointed a vice president of long COVID last year. Bishoy Rizkalla now oversees a small team studying how the company’s messenger RNA shots could mitigate problems caused by new and latent viruses, including SARS-CoV-2. But Rizkalla says Moderna has no federally funded projects in long COVID.

Federal bureaucracy has slowed down research in other ways. When long COVID appeared, Tonix Pharmaceuticals was developing a possible drug called TNX-102 SL to treat fibromyalgia. The two conditions look similar: they’re painful, fatiguing, and multisystemic, and fibromyalgia can crop up after a viral infection.

But it wasn’t easy to design a study to test the compound in long COVID. Among other issues, the US Food and Drug Administration initially insisted that participants have a positive COVID-19 test confirmed by a laboratory, like a polymerase chain reaction test, to be included in the study. At-home diagnostics wouldn’t count.

“We spent a huge amount of money, and we couldn’t enroll people who had lab-confirmed COVID because no one was going to labs to confirm their COVID,” cofounder and CEO Seth Lederman says. “We just ran out of time and patience and money, frankly.”

Tonix had planned to enroll 450 participants. The company ultimately enrolled only 63. The study failed to meet its primary end point of reducing pain intensity, a result Lederman attributes to the smaller-than-expected sample size.

TNX-102 SL trended toward improvements in fatigue and other areas, like sleep quality and cognitive function, but Tonix is moving away from developing the compound as a long COVID treatment and focusing on developing it for fibromyalgia. If it’s approved, Lederman hopes that physicians will prescribe it to people who meet the clinical criteria for fibromyalgia regardless of whether their condition stems from COVID-19.

“I’m not saying we’re not going to do another study in long COVID, but for the short term, it’s deemphasized,” Lederman says.

Abandoned attempts Without more public or private investment, it’s unclear how research can proceed. The small corner of the private sector that has endeavored to take on long COVID is slowly becoming a graveyard.

Axcella Therapeutics made a big gamble in late 2022. The company pivoted from trying to treat nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, a liver disease, to addressing chronic fatigue in people with long COVID. In doing so, Axcella reoriented itself exclusively around long COVID, laying off most of its staff and abandoning other research activities. People in a 41-person Phase 2a trial of the drug candidate, AXA1125, showed improvement in fatigue scores based on a clinical questionnaire (eClinicalMedicine 2023, DOI: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101946), but Axcella shut down before it could get its planned 300-person follow-on study up and running.

The fate of AXA1125 may be to gather dust. Axcella’s former executives have moved on to other pursuits. Erstwhile chief medical officer Margaret Koziel, once a champion of AXA1125, says by email that she is “not up to date on current research on long COVID.” Staff at the University of Oxford, which ran the Phase 2a study, were not able to procure information about the planned Phase 2b/3 trial. A spokesperson for Flagship Pioneering, the venture firm that founded Axcella in 2011, declined to comment to C&EN.

Other firms have met similar ends. Ampio Pharmaceuticals dissolved in August after completing only a Phase 1 study to evaluate an inhaled medication called Ampion in people with long COVID who have breathing issues. Biotech firm SolAeroMed shut down before even starting a trial of its bronchodilating medicine for people with long COVID. “Unfortunately we were unable to attract funding to support our clinical work for COVID,” CEO John Dennis says by email.

Another biotech company, Aerium Therapeutics, did manage to get just enough of its monoclonal antibody AER002 manufactured and in the hands of researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, before it ended operations. The researchers are now testing AER002 in a Phase 2 trial with people with long COVID. Michael Peluso, an infectious disease clinician and researcher at UCSF and principal investigator of the trial, says that while AER002 may not advance without a company behind it, the study could be valuable for validating long COVID’s mechanisms of disease and providing a proof of concept for monoclonal antibody treatment more generally.

“[Aerium] put a lot of effort into making sure that the study would not be impacted,” Peluso says. “Regardless of the results of this study, doing a follow-up study now that we’ve kind of learned the mechanics of it with modern monoclonals would be really, really interesting.”

‘A squandered opportunity’ In 2022, the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) put about $577 million toward nine research centers that would discover and develop antivirals for various pathogens. Called the Antiviral Drug Discovery (AViDD) Centers for Pathogens of Pandemic Concern, the centers were initially imagined as 5-year projects, enough time to ready multiple candidates for preclinical development. The NIH allocated money for the first 3 years and promised more funds to come later.

The prospect excited John Chodera, a computational chemist at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and a principal investigator at an AViDD center called the AI-Driven Structure-Enabled Antiviral Platform. Chodera figured that if his team were able to develop a potent antiviral for SARS-CoV-2, it could potentially be used to treat long COVID as well. A predominant theory is that reservoirs of hidden virus in the body cause ongoing symptoms.

But Chodera says NIAID told him and other AViDD investigators that establishing long COVID models was out of scope. And last year, Congress clawed back unspent COVID-19 pandemic relief funds, including the pool of money intended for the AViDD centers’ last 2 years. Lawmakers were supposed to come through with additional funding, Chodera says, but it never materialized. All nine AViDD centers will run out of money come May 2025.

“When we do start to understand what the molecular targets for long COVID are going to be, it’d be very easy to pivot and train our fire on those targets,” says Chanda from Scripps’s AViDD center. “The problem is that it took us probably 2 years to get everything up and going. If you cut the funding after 3 years, we basically have to dismantle it. We don’t have an opportunity to say, ‘Hey, look, this is what we’ve done. We can now take this and train our fire on X, Y, and Z.’ ”

Researchers at multiple AViDD centers confirm that the NIH has offered a 1-year, no-cost extension, but it doesn’t come with additional funds. They now find themselves in the same position as many academic labs: seeking grant money to keep their projects going.

Worse, they say, is that applying for other grants will likely mean splitting up research teams, thus undoing the network effect that these centers were supposed to provide.

“Now what we’ve got is a bunch of half bridges with nowhere to fund the continuation of that work,” says Nathaniel Moorman, cofounder and scientific adviser of the Rapidly Emerging Antiviral Drug Development Initiative, which houses an AViDD center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“This was a squandered opportunity, not just for pandemic preparedness but to tackle these unmet needs that are being neglected by biotech and pharma,” Chanda says.

Viral persistence Ann Kwong has been here before. The virologist was among the first industry scientists trying to develop antivirals for hepatitis C virus (HCV) back in the 1990s. Kwong led an antiviral discovery team at the Schering-Plough Research Institute for 6 years. In 1997, Vertex Pharmaceuticals recruited her to lead its new virology group.

Kwong and her team at Vertex developed a number of antivirals for HCV, HIV, and influenza viruses; one was the HCV protease inhibitor telaprevir. She recalls that a major challenge for the HCV antivirals was that scientists didn’t know where in the body the virus was hiding. Kwong says she had to fight to develop an antiviral that targeted the liver since it hadn’t yet been confirmed that HCV primarily resides there. People with chronic hepatitis C would in many cases eventually develop liver failure or cancer, but they presented with other issues too, like brain fog, fatigue, and inflammation.

She sees the same dynamic playing out in long COVID.

“This reminds me of HIV days and HCV days,” Kwong says. “This idea that pharma doesn’t want to work on this because we don’t know things about SARS-CoV-2 and long COVID is bullshit.”

Since January, Kwong has been cooking up something new. She’s approaching long COVID the way she did chronic hepatitis C: treating it as a chronic infection, through a start-up called Persistence Bio. Persistence is still in stealth; its name reflects its mission to create antivirals that can reach hidden reservoirs of persistent SARS-CoV-2, which many researchers believe to be a cause of long COVID.

“Long COVID is really interesting because there’s so many different symptoms,” Kwong says. “As a virologist, I am not surprised, because it’s an amazing virus. It infects every tissue in your body. . . . All the autopsy studies show that it’s in your brain. It’s in your gut. It’s in your lungs. It’s in your heart. To me, all the different symptoms are indicative of where the virus has gone when it infected you.”

Kwong has experienced some of these symptoms firsthand. She contracted COVID-19 while flying home to Massachusetts from Germany in 2020. For about a year afterward, she’d get caught off guard by sudden bouts of fatigue, bending over to catch her breath as she walked around the horse farm where she lives, her legs aching. Those symptoms went away with time and luck, but another round of symptoms roared to life this spring, including what Kwong describes as “partial blackouts.”

Kwong hasn’t been formally diagnosed with long COVID, but she says she “strongly suspects” she has it. Others among Persistence’s team of about 25 also have the condition.

“Long COVID patients have been involved with the founding of our company, and we work closely with them and know how awful the condition can be,” Kwong says. “It is a big motivator for our team.”

Persistence is in the process of fundraising. Kwong says she’s in conversations with private investors, but she and her cofounders are hoping to get public funding too.

On Sept. 23, the NIH is convening a 3-day workshop to review what RECOVER has accomplished and plan the next phase of the initiative. Crucially, that phase will include additional clinical trials. RECOVER’s $1.7 billion in funding includes a recent award of $515 million over the next 4 years. It’s not out of the question that this time, industry players might be invited to the table. Tonix Pharmaceuticals’ Lederman and Aim ImmunoTech’s McAleer will both speak during the workshop.

The US Senate Committee on Appropriations explicitly directed the NIH during an Aug. 1 meeting to prioritize research to understand, diagnose, and treat long COVID. It also recommended that Congress put $1.5 billion toward the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H), which often partners with industry players. The committee instructed ARPA-H to invest in “high-risk, high-reward research . . . focused on drug trials, development of biomarkers, and research that includes long COVID associated conditions.” Also last month, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) introduced the Long COVID Research Moonshot Act, which would give the NIH $1 billion a year for a decade to treat and monitor patients.

It’s these kinds of mechanisms that might make a difference for long COVID drug development.

“What I’ve seen a lot is pharma being hesitant to get involved,” says Lisa McCorkell, a cofounder of the PLRC and a coauthor of the recent long COVID review. “Maybe they’ll invest if NIH also matches their investment or something like that. Having those public-private partnerships is really, at this stage, what will propel us forward.”

Chemical & Engineering News ISSN 0009-2347 Copyright © 2024 American Chemical Society

#mask up#covid#pandemic#wear a mask#covid 19#public health#coronavirus#sars cov 2#still coviding#wear a respirator#long covid#covid conscious#covid is not over#wear a fucking mask

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

I wish there was more research done on the chronic fatigue that many autistics have due to autism.

Many of us don't meet the criteria for CFS, but still suffer from chronic fatigue regardless.

I honestly feel like if my chronic fatigue was under control or if I didn't have it at all, then I'd likely be a lot more capable at doing things bcus I'd have the energy for it.

What kind of things you ask? Drawing, video games, work, hanging out with friends, going out to places that interest you, appointments that are genuinely needed, education and learning, and more.

Would I still be disabled by my autism? Absolutely, yes. Chronic fatigue doesn't change that. What it does change is what I can do to help myself.

There's a whole world waiting for me that I don't have access to bcus I need to limit how much I do in my week due to fatigue.

I am so tired all the time and everything in my life takes the same level of energy from me. The more I do, the double to triple amount of recovery time is needed.

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

cfs/disability blog post -__-

finally acclimated enough to become bold enough to talk about it. after getting sepsis and then getting covid for the first time while in the ICU in late 2022, i have developed chronic fatigue syndrome. i don't like that diagnostic title but it is what it is until further discoveries of categorization and naming of specific mechanisms of its causes are made, and it's the most well known term.

there is something wrong in my body. i can tell. I hate the concept of it being "fatigue" - it's inability to recover from exertion. my favorite term is actually from 2015: systemic exertional intolerance disease (SEID). i have the dubious advantage in being able to articulate and understand clearly what's going on because I'm a person who has previously recovered from near-bedridden levels of weakness from a series of life circumstances and choices that left me barely able to stand and walk. once i was out of the circumstances that resulted in this, I recovered slowly but surely. the concept of self-rehab is simple: exercise to near exertion or exertion, eat nourishing foods that allow muscles to rebuild, rest if you're overtired or hurt. continue this cycle. enjoy how it feels to get stronger and the simple joy and fun of being exerted! this worked great for me. it was only getting better.

i was undaunted at recovery after sepsis/COVID because i'd done it before. then, when things were different, i just thought i needed to push through and keep going. this resulted in me acting extremely erratically and being incredibly unwell for a year. then i started taking seriously that something was wrong. and it is wrong, i just can't stress enough that something is wrong in my body.

this is how exercise (exertion) used to go: the exercise starts, there is a wonderful beginning feeling of ecstasy, excitement, followed by a middle feeling of being fully present, fully engaged with the physical activity, then an ending feeling of pleasant exertion (sometimes quite intense!), then the satisfaction of resting, eating, drinking. sore the next day if boundaries were pushed, not if they weren't.

this is how exertion goes now: the exercise starts. there IS a wonderful beginning feeling of excitement. i think one of the worst parts is how it always pretty much feels okay at the beginning, and because i am an optimist (possibly born this way, nothing has ever been able to really stop it), i think i might actually get away with it this time. consider this: a brief and brisk outing to a nice norcal town, maybe 30 minutes total of walking and standing, with rest interspersed, total 1.5 hour outing. the middle feeling of the exertion has changed. there is a sensation that something is wrong, something is off. it's incredibly difficult to not just push through this. but the end is definitely the worst. instead of a pleasant exertion, there is a sudden oncoming rush of emptiness, oncoming illness. where there used to be satisfaction there's just a sensation of doom. sometimes it feels like i'm falling, like literally falling through space while sitting still.

within 8-12 hours, there is a result of something going wrong in the body. some research suggests it's a mitochondrial problem. i don't know. i'm not science-y enough. but it's just fucking crazy. feeling like you do when you wake up and realize you got that flu after all, cognitive functioning sharply declines, shaky, can't focus, lose short-term memory, can't type well on my phone, loss of ability to emotionally regulate, a spike in aphasic issues. my "post exertional malaise" symptoms are mostly cognitive functioning based, i have to go pretty far before i start feeling it physically. which is incredibly frustrating in its own right, to feel the sensation of untapped power in my body. and when i take it too far, i can put myself into a spiral of being fucked up for weeks or months (when i REALLY fuck up and keep going. just finished one of these. months. really months)

it just sucks. i'm constantly trying new things, trying to treat it, trying to improve. i take resting really seriously now but i just can't accept i'll spend the rest of my life like this. there's a few camps in CFS subculture, people who say recovery isn't possible (and often tell anyone aiming for it they're just going to make themselves worse), people who insist recovery is possible (and do not make space for people who have tried everything and nothing worked), and many more ad infinitum.

i right now believe i'm on a slow but linear improvement timeline. a woman once told me her mother had issues like this after sepsis and she felt better 10 (!) years later. it's been 2.5 years for me and i can do more. but how much of "doing more" is just me sacrificing a lot of things in my life i used to be able to to do rest (more cooking, cleaning, etc.) it's humbling. my gf takes care of me in a way that is impossible to articulate my thankfulness for. like she saved me and is the reason i'm alive. she is devoted and caring to the extreme

i am really serious about disability politics and being ok with being disabled. and it feels like (as an ex-christian who will live with genuine serious religious trauma for the rest of my life) that god is always humbling me/punishing me. but this isn't a punishment from god. it's a medical problem. and there are going to be different approaches and medical solutions. and as long as i don't give up i will improve.

i just feel like i need to talk about this. i've been really ashamed because it's a really crazy catch-all diagnosis, and also i do not really engage with the sprawling massive community around it, because like most internet communities focused on mental/physical health issues, they are often hostile to a position of openness and curiousness and also a true desire for improvement in whatever ways are availble/good disability politics

i was definitely in the CFS skeptic group before developing it (which also feels like a punishment from god), and i feel more ashamed of that than almost anything else. not like i was a hater or arguing with anyone online about it, but i had my reservations. and now i understand that there is something fucking wrong in my body, this is not normal. the body is not doing what it's supposed to do. there is a breakdown in the natural order of things. so if you are a skeptic please know i get it. and i am here to tell you that something is happening lmao THIS is not. normal

so basically if you have CFS/long covid/post-viral whatever i believe you. and i hope you believe me too. talking to doctors about this has been the fucking worst and i am a pretty medically stigmatized person to begin with. i believe you. and i also do believe there's hope in many different directions. fucking KIDS are getting it now because of COVID. this administration fucked up a lot of research but other countries are trying. i think we'll have more understanding and approaches within a decade.

i just make meaning of things by writing about them and i'm really tired of guarding this like a secret i don't want anyone to know like so many other things in my life i've now successfully written about and worked through by forming narrative meaning. so this is a first stab at that and thank you for reading

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think, even from within the disabled community, everybody has got to stop dismissing and downplaying ME/CFS as "it's just chronic fatigue".

It's a neuroimmunological disease. It's a devastating chronic illness and physical disability, described by those who live with it as a "living death". It's no less debilitating than multiple sclerosis and it's still far less understood. People have died from it (by suicide and not by suicide). Numerous lives have been wrecked by it. There's no medication for it and no proven effective treatment as of today. Recovery rate is optimistically 6%.

#cripple punk#spoonie community#disabled community#disability advocacy#me/cfs#millions missing#chronic fatigue warrior#chronic illness warrior

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm glad folks seem to like my light and effort photography post because I nearly melted my brain trying to write it. Every long post I write usually takes several days and a lot of mental discomfort. But I need to write for my sanity, so I keep on keepin' on.

My recovery is going so slow. In two months I have reduced the dose of the offending medication by 75%. Which sounds like a great success when you say it out loud, but it feels pretty miserable most of the time. The last 25% is proving to be much harder.

It is kind of a mindfuck because the worse I feel the more progress I am making. When I feel shitty, I feel productive. When I don't feel as bad, I feel guilty for slowing my progress.

I am bored because I struggle to concentrate. I am lonely because it is very hard to communicate with friends. My CFS is greatly exacerbated to where it feels like my limbs weigh a thousand pounds. My house continues to be a disaster zone because I can't clean. I barely have any counter space because I am too tired to wash dishes.

I've reached that point of desperation where I keep cleaning the same spoon over and over again.

I have simplified my self care to food, medicine, and sleep. I make sure I am eating. I make sure I take my meds. And I make sure I get as much sleep as possible. I will sort the rest out later.

I haven't been able to do any photography or photo editing in the last 4 months. I miss it very much. But creating that post and giving out photography advice helps a little. Even if it was difficult to write.

It's weird looking at my photography from over 7 years ago. It feels good that a lot of it still holds up. But I know so much more than I used to. Especially when it comes to studio lighting. I have all of this unrealized potential and no energy to create new photos. I have leveled up so much and it is frustrating when I can't show off what I'm capable of now. But I'm hoping if my recovery is successful I can finish building my home studio and photograph cool shit.

In the meantime, I do find photography education rewarding when I have the energy. If my body was fully cured tomorrow I think I would try to be an actual teacher of photography. I really enjoy sharing what I've learned and I think I am pretty good at it. The internet has been a great resource for knowledge but lately it feels like there is a lot of educational noise. It is really difficult for beginners to tell the difference between good and bad information. I look at some of these threads in the "Ask Photography" subreddit and many of the answers make me cringe.

I feel bad because I could really help some of these folks seeking answers but they are stuck with people who aren't really suited to educate. Either they don't know what they don't know and are too confident in their current expertise—causing slightly inaccurate to straight up confusing to blatantly wrong answers.

Or they do know their shit but are patronizing and arrogant to newbies.

I won't lie, there *are* stupid questions. But it is still best practice to act as if there are no stupid questions.

It's hard for me to criticize too much because I started a photography education Tumblr way before I was qualified to do so. I really thought I knew what I was talking about but I did not fully understand what I was teaching. I was mostly parroting what I heard from actual qualified educators. Thankfully when I look back at those posts all of the information is fairly accurate. It seems my saving grace was selecting good teachers.

Knowledge is so weird. You can have the correct information in your brain. You can use that information to get good results. But it is entirely possible to not understand that information.

I actually had a personal "eureka!" moment where everything unlocked almost all at once. I was watching a tutorial and the teacher talked about "image forming reflections" and it felt like every neuron in my brain fired at the same time. I had an epiphany and ever since I have had a deep understanding of light.

Just a single phrase inspired a realization that caused a cascade of other realizations. I've never experienced anything quite like that.

Have any of you ever had an epiphany like that? Aside from that single instance, I've only had mini-epiphanies. Like when I realized the moon is just constantly falling and missing the earth. My brain always imagined astronauts and satellites and the moon as things floating out in space. But everything in the universe is just free falling... all the time. Tom Petty knows what I'm talking about.

But that baby epiphany failed to unlock understanding for all of quantum gravity.

What was this post about?

I think I rambled into a few tangents.

In any case, I feel like crap and that's fantastic.

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

I haven’t publicly said anything about this yet but it’s really weighing on me, so:

I have an oncology appointment next Tuesday.

I’ve been growing more and more tired by the day, which is to say energy is almost nonexistent now. I already have CFS pretty badly, so this drain is completely ruining my quality of life. I can barely do the basic things to take care of myself, never mind the things that I enjoy.

And it’s breaking me.

I want to write and read and create art and pick up that electric violin my partner got me and play video games and—

You get the picture.

Sitting upright is a drain of energy. I have to save a lot of spoons for meal times so I can sit up and eat.

And, oh, yeah, have hardly felt a single hunger signal in about 3 weeks. I’m keeping up with eating to take my meds and because it’s a habit I made for myself in my eating disorder recovery. It’s so fucking hard to do right now though.

I’m now rapidly dropping weight despite changing nothing about my lifestyle save for the fact that I’m even more sedentary than before. I won’t get into my actual weight, but have been seeing my doctor rather frequently to keep track of all this, and I lost 11 pounds in 2 weeks. I just saw my doctor yesterday, and obviously we both found that pretty alarming. I’ve been losing weight over the past two months, but the rate it’s happening at is definitely increasing.

And to tie it all together? My blood work results are bad. Climbing white blood cell count with no sign of an infection, and it doesn’t seem to correlate with my steroid dosage or endocrine system. We went through all my meds and the doctor is pretty damn sure none of them are causing this increase in white blood cells. Not only that, but my neutrophils are very high, as are my immature grans. (Both are different types of blood cells. I have been learning a lot about blood lately.)

So, um, yeah…

Cancer Scare #3. This feels a lot more real than the last two though. Scare #1 was because of high red blood cell count, but that evened out. They’re even at normal levels now! Scare #2 was the multiple tumors in my liver. Those turned out to be hepatic adenomas caused from long term birth control usage, so they were benign, and have since gone away now that I’ve stopped taking Depo Provera.

This is just… very different. Even if it’s not a type of blood or bone marrow cancer, there is something seriously wrong inside my body. It’s terrifying to me. I had a baseline I’d adjusted to with my body and knew what symptoms to expect from it. A chronically ill body is often very unpredictable, but it was still a body I knew and recognized and had grown used to.

I don’t know my body anymore. Not even a little bit. I just feel physically ill all the time, and the brain fog from it is so bad that it’s starting to scare me. My memory is just not there. There’s been a definite decline in my cognitive abilities.

Originally my appointment was May 13th, but I was the top priority on the cancellation list, so it got moved to April 29th. While it feels good to be taken seriously, it’s being taken so seriously that it’s frightening.

I hate this.

I’m not even getting into how this has affected my mental health.

Thank you if you read through all this. It turned out much longer than I expected it to. I’ve told most of my loved ones, but I just needed another place to share it.

TLDR: Buckle up for Archer’s Cancer Scare #3

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abled people don't fucking get it.

You don't get to imply I'm living some kind of "forever vacation". It's perpetual pain. If you see me doing something I enjoy, it's not because it's what I'd rather be doing than being "productive". I fucking miss the gym but things like video games are just a much more accessible activity these days. I'm not "lounging", I don't get a break from the pain just that sometimes I'm able to take my mind off of it

Unemployment isn't some kind of break or excuse to not participate in society (capitalism is garbage but being disabled=/=unemployed for the hell of it). For reasons, I fell behind in school, bad. But I got myself a diploma equivalent and finally felt I'd chosen the line of work I wanted. I had connections, opportunities. I had fibro and some fatigue (unknowingly CFS as that was manageable) but I was getting PT and managing it as best I could. All I needed was to take courses and I was ready for that even with the difficulty of my then undiagnosed ADHD.

And then I got sick, really sick. Worst mono infection my doctor had ever seen due to medical neglect, Shoutout to those shitty CVS minute clinics. It made my ME/CFS so much worse, I was stuck in bed all the time before getting put on Adderall for my then newly diagnosed ADHD. Then I thought the fatigue was finally healing and a side effect of Adderall was a huge crash and wave of fatigue. No it turns out when it wore off I just felt the fatigue again lmfao

I was told I'd be better within 6 months. Okay so I can opt for the Spring semester, no big deal. 8 months go by, a year, a year and a half. I waited and waited. Hoping that "when I get better" I could be caught up with everyone else I knew my age. That was over 7 years ago. Do people think I wanted that all taken from me? To get progressively worse and worse?

Do they think loss of agency is something I enjoy? Needing help, being unable to drive, to enjoy my old hobbies, cook for myself regularly? I've been accused of enjoying this and not wanting to get better as if this hasn't put my head in very dark places. Sometimes I feel like I see a way out of this and it isn't recovery. They don't get it. I don't enjoy being heavily medicated but I know I need to be. I don't enjoy having things purchased for me because I want more financial independence. I don't enjoy feeling like a leech, actually.

It's not a vacation, it's hell. You can go on about how much more exhausted you are because you work or whatever but the thing is I don't need a job to feel what you feel after working. I feel like I worked a 12 hour shift after taking a shower on some days, no exaggeration. You can't compare your able bodied exhaustion to the effects of a chronic illness that fucks you up without you needing to work a full time job. This is my full time job and it wasn't the one I was hoping for exactly

#chronic pain#disability#chronic illness#fibromyalgia#cfs#chronic fаtiguе ѕуndrоmе#actually disabled#spoonie#me/cfs#cfs/me#long covid

382 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The 1% Solution" By Bruce Campbell

Comment: "Getting better" can mean recovering or simply improving. I personally think full recovery from management strategies is unlikely for a lot of people with ME/CFS

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

A need for more (positive) stimulation

If I’d planned it in advance, this year couldn’t have been much more stimulating, it’s been coming at us as though out of a fire hose. One thing we’ve done, in spade loads, is move about…so much so that I noticed this morning how packing has now become a fine art; we both “get to it” like a military operation, falling into our routines and responsibilities like a well-oiled machine. Not…

View On WordPress

#ADHD#articles#chronic illness#fulfilment#ME/CFS#need for challenge#need stimulation#positive excitement#recovery#recovery from chronic illness cycle#satisfaction#self-confidence#task completion#use it or lose it#variety

1 note

·

View note

Text

In the Quiet of Healing: My Journey with the Parasympathetic Nervous System

Healing Through Rest: How the Parasympathetic Nervous System Can Support Recovery from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome In the aftermath of the recent hurricanes, Helene and Milton, I’ve felt post-exertional malaise weigh heavily on my body. The fatigue has been more than just physical—it’s emotional and mental, a deep, enveloping weariness that reminds me how fragile recovery can be. As I continue to…

#breathwork for fatigue#calming the nervous system#chronic fatigue strategies#chronic fatigue syndrome#chronic illness recovery#deep rest techniques#energy conservation#Feldenkrais Method#fight or flight response#gentle movement practices#healing from hurricanes#healing through rest#health#holistic healing#Managing chronic fatigue#ME/CFS#meditation#mental health and chronic fatigue#mindfulness for fatigue#nervous system regulation#pacing for chronic illness#Parasympathetic Nervous System#post-exertional malaise#recovery from exhaustion#Relaxation techniques#restorative yoga#self-care for chronic illness#yoga#Yoga Nidra for healing

1 note

·

View note

Text

I am getting through one of the worst mental health crises I have ever had. I'm actually succeeding at overcoming it faster than I thought I would. Shit just keeps happening. So... details, because writing and sharing crap can help:

Both our cats passed away last year; one early, one late. Just after the second passed away (and hers was a shock), we got hit by two hurricanes. I then had a massive multiple months' long ME/CFS crash during which I couldn't even sit up to eat for a while. During which, the election and our ongoing horror due to it. Related to the hurricanes AND the election, the hurricanes flooded our car so we had to get a new one. We weren't too worried about FEMA helping us out there, but now they haven't yet. Related to THAT, we moved in December (and moving is of course always stressful), in large part to save money on rent. We thought we were no longer going to be so thoroughly broke because of this, but then we had to buy a new car due to hurricanes, which FEMA isn't helping with due to the orange monstrosity.

Then I needed a lot of dental work. And they have started cutting down trees behind our apartment. This is deeply depressing, for one thing. For another, it is LOUD. My nervous system does not handle loud well, and my emotions do not handle tree death well.

So then my computer died utterly. The computer guy said he could recover most things, but he was wrong. My Sims 2 stuff from the past 10 years is gone. I am deeply depressed by this. A whole lot of other stuff is also gone, and not just from the past 10 years, but from the past 20+. He was able to save all my documents and pics, but I'm still in the denial stage of mourning for basically everything else.

Speaking of dental work, I kept being told that while getting a wisdom tooth out was rough (it was but not as bad as I feared), dental fillings were no problem at all because they didn't hurt while getting them these days. This is true! And the little pain I have afterward, I'm able to control with Advil and Tylenol. However, it took an hour and was far worse than I'd anticipated, simply because what causes me problems (see: sensitive nervous system) is not what causes other people problems, apparently.

They are loud outside right now. A little bit farther away than they have been. I don't know if they're done with their tree murder spree. Basically, what I need for full recovery is not happening and I don't know when it will happen. It is entirely outside of my control.

It is a very, very, VERY good thing that Calliope adopted us. I won't get too into it, but there were a couple days when she was all that was keeping me hanging on.

ETA: One of my problems is that I have an even worse sense of time than usual. Our cats passed away in 2023. Then October 7 happened, and over that period, I had a really bad stomach flu. I don't remember most of 2024.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

extreme fatigue and fogginess?

hi! if you're super fatigued you should rule out sleep apnea, 80% of people with it are undiagnosed, 1 in 5 people has it. it's when your airway collapses when you are sleeping. it's unsurprisingly seriously bad for your health for you to stop breathing while you're sleeping and even apparently puts you at risk for a higher chance of 'sudden death' (terrifying, and why I am gonna give my new cpap machine a real try).

just a psa because i have had chronic fatigue (the symptom and also likely me/cfs, unless i make a miraculous recovery) and needed a sleep study for a long time and lo and behold i have it, i stop breathing 12 times an hour. some people like my dad have apneas like 45 times an hour. take it seriously. here's hoping the cpap helps with my fatigue, i have heard glowing reviews from several people.

also if you are in the US and able to fork over $180, i have heard someone recommend lofta, you can get the sleep test equipment sent to your house and a prescription for a cpap if you have it. you can't get a cpap without a script.

if you don't have it and/or it doesn't make a significant impact, many people are developing me/cfs as a result of postviral illness (even if you had asymptomatic covid, 60% of cases are and they still cause damage to your body). this also could be you, get some bloodwork and start ruling things out if you can.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Also preserved in our archive

The cost is set to go far beyond human suffering, yet almost five years into the pandemic, not only are there still no treatments for long Covid, there aren’t even any diagnostic tools – and we don’t seem overly interested in finding them.

The jig is up. People are catching on that “mild” Covid-19 may not be so mild, and that the mysterious lingering symptoms they’ve experienced after catching the virus, such as fatigue and brain fog, may just be connected. For others, this will be the first time that they put two and two together. I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but strap in for what comes next.

Recently, RNZ ran a piece outlining the estimated $2bn per year economic cost of long Covid in New Zealand and signalling that further research would be needed to determine a more precise figure. The average reader would assume that this research is under way or has at least been planned and funded. Human suffering aside, such a hit to productivity would surely raise alarm bells across the political spectrum!

I say this solemnly: yeah… nah.

Almost five years into the pandemic, not only are there still no treatments for long Covid, there also aren’t even any diagnostic tools – and we don’t seem overly interested in finding them.

At present, a long Covid diagnosis relies on a patient finding a doctor with up-to-date knowledge, who will believe their symptoms, and who will spend time investigating further to rule out other possibilities. This mythical trifecta is out of reach for most people, particularly women, who are affected by immune conditions at far higher rates, but have their symptoms written off as hysteria; and Māori and Pasifika, who face barriers to healthcare, and have their symptoms written off as laziness. Obtaining accurate data on prevalence under these circumstances is simply impossible.

In this way, and several others, long Covid mirrors ME/CFS (myalgic encephalomyelitis), a brutally debilitating biophysical condition, though the oft misused term “chronic fatigue” doesn’t quite convey that. Around half of long Covid sufferers meet the criteria for ME/CFS, which by the World Health Organization’s scale has a worse disease burden than HIV/Aids, multiple sclerosis (MS), and many forms of cancer. But again, there are no treatments.

I suffer from ME/CFS myself. My illness predates Covid-19 and came on after an infection with cytomegalovirus (CMV). I went from a fit and active young man to debilitatingly sick and fatigued, with several unexplained symptoms.

Pre-pandemic there was estimated to be more than 25,000 people in New Zealand suffering from ME/CFS, and only one specialist in the country, working one day a week, who has since retired (well earned, bless her). For years I had been praying for any sort of diagnosis, even if it was bad, so that I could get on the path to recovery. I got the diagnosis – but for a disease with no path to recovery.

As the pandemic unfolded, patients and advocates in the ME/CFS community warned that a tsunami of disability was approaching. They were of course ignored, as they have been for decades, and are now joined by masses of long Covid sufferers facing the reality that the medical profession has no answers for them, except perhaps euthanasia.

Frustrated with my lack of options, I connected with cellular immunologist Dr Anna Brooks, who had become a leading expert on long Covid, so I assumed that her biomedical research would be well supported. Alas, she detailed the uphill grind that it’s been to gain traction compared to other countries, and that generous donations, usually from patients themselves, had been the driving force of funding.

Together we founded DysImmune Research Aotearoa, with the goal of developing diagnostic tools leading to treatment for post-viral illnesses like long Covid and ME/CFS. In layman’s terms, we collect blood samples, analyse differences in cells, and put together an immune profile. My priority is ensuring that Māori and Pasifika patients and researchers are at the table and taking action into our own hands.

We’ve made a small start, and we have some incredible collaborations lined up, with far-reaching implications for community health. We’re in the process of seeking partnerships to take things forward. The expertise exists, it’s here in New Zealand. Still, the barrier to progress across the research space is the urgency for resourcing. It is dire to say the least.

Without some long-term project certainty, it’s difficult to pull the necessary teams together. While study after study illuminates more horrifying long-term effects of Covid infections, and prevention has been completely abandoned, research and development for treatments for long Covid is tanking. The private sector is at the whim of the quarterly financial report, and with no guaranteed short-term profit in treating us, it has very little incentive to take the risk.

So, barring some philanthropic miracle, only government can fill this gap. Yet where Australia had set aside A$50m specifically for long Covid research, and the US Senate considers a billion-dollar long Covid “moonshot” bill, New Zealand has allocated nothing. We’re fast asleep at the wheel. No other country can determine how many of our people are impacted by post-viral illnesses. No other country can address our specific needs.

Since this government is focused on ambition, productivity and fast-tracking, I assume they’d want to be world leaders in research, warp-speed some projects, and get long Covid sufferers back into work, no? This is what we are calling for. Not surveys. Not “talk” therapy and positive thinking. Biomedical research.

Put the money down and commit to this. Seize this opportunity to right decades of neglect. There are tens of thousands of us fighting for our lives, and millions more around the world. You think it won’t be you, then after your next inevitable Covid-19 reinfection, it is, and you’re left to wonder why nobody stepped up.

Government, iwi and whānau ora groups, health organisations, philanthropists – reach out. Let’s work.

Rohan Botica (Te Ātihaunui-a-Pāpārangi, Ngāti Tūwharetoa) is a lived-experience researcher and co-founder of DysImmune Research Aotearoa.

#mask up#covid#pandemic#public health#wear a mask#covid 19#wear a respirator#still coviding#coronavirus#sars cov 2#long covid#covidー19#covid conscious#covid is airborne#covid isn't over#covid pandemic#covid19#the pandemic isn't over

29 notes

·

View notes