#relational trauma

Text

Giving in to self-destructive behaviors and sticking it through in recovery are both painful and exhausting, but only one is suffering in the right direction.

#affirmations#eating disoder recovery#trauma recovery#anorexia#bulimia#osfed#cptsd#ednos#mental health#reminder#self care#eating disorder#binge eating#relational trauma#childhood trauma#trauma#recovery

725 notes

·

View notes

Text

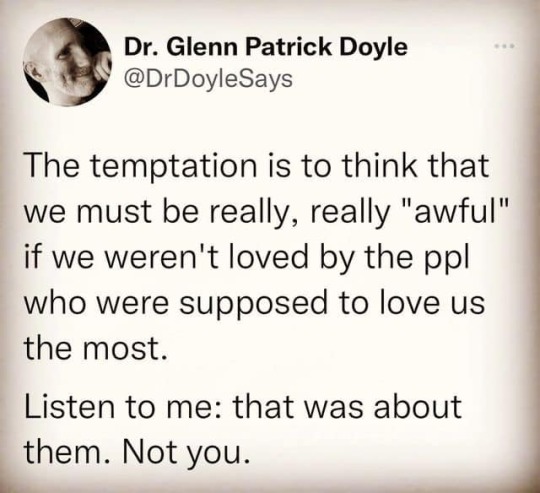

"That was about them. Not you."

Source: Dr. Glenn Doyle

#healing#recovery#growth#Dr. Glenn Doyle#life#living#love#self-love#self-awareness#trauma#childhood trauma#relational trauma#relational patterns

133 notes

·

View notes

Photo

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Alastair Mordey

Published: Jun 4, 2023

You may have noticed over the last decade a steady increase in the promiscuous use of the word ‘trauma’. A word that once referred exclusively to grievous injuries of body and mind (gun-shot wounds, PTSD, that sort of thing) can now describe virtually anything. Psychotherapists and clinical psychologists are the main super-spreaders of this hyperbolic virus, though educators, politicians and of course celebrities are now getting in on the act.

But trauma is more than just an annoying buzz word. Its inexorable creep into common parlance is the culmination of aa sustained campaign to politicise healthcare that has been going on for 30 years. Along the way it has resurrected some of Sigmund Freud’s more bizarre theories about childhood development, and married them with social justice concerns to become what is effectively a secular religion.

Anyone who is familiar with the work of Sigmund Freud knows that his psycho-sexual theories developed in two distinct stages. The first posited that people who were mentally or emotionally unwell had repressed traumatic memories (almost always of sexual abuse in their childhood). He eventually gave up on this theory. In its stead he developed his equally infamous theory of infantile sexuality, in which children experienced sexual feelings through different erogenous zones during distinct stages of their development. It may surprise and horrify you to learn that both theories are alive and well in the current mental healthcare establishment, where they have been rebranded into a pseudoscientific theory about childhood trauma that leads to brain damage, addiction, and disease.

This Freudian reformation began in the 1990s with the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. The ACE study as it became known, was conducted between 1995 and 1997. The lead researcher was a physician called Vincent Felitti, who worked at Kaiser Permanente’s Department for Preventative Medicine in San Diego. Dr Felitti ran a weight loss programme at Kaiser, and he had a problem. His obese patients kept dropping out. Not only that, it was the ones who were doing well who were dropping off the most. Confused by this, Felitti conducted follow up interviews with as many of those patients as he could, and what he found was shocking. Out of the 286 interviews, a significant amount reported that they had been sexually abused as children. These revelations caused Felitti to reflect on Freud’s psycho-sexual theories. What if his patients had grown up using their obesity as a protective mechanism to deter sexual predation? Maybe that was why they were unwilling to lose too much weight. Or what if comfort eating was some kind of self-medication? An ‘oral fixation’ which compensated for the nurturing they should have received as children?

Inspired by these hypotheses, Felitti approached colleagues at the Center for Disease Control and set about designing the ACE study. The study asked some 17,000 patients in California’s healthcare system ten questions about adverse experiences in their childhood (which they dubbed ACEs). Specifically they asked them questions about three types of abuse (physical, sexual, and psychological); two types of neglect (physical and emotional); and five different types of household dysfunction (exposure to mental illness, substance abuse, domestic violence, criminal behaviour, and divorce or separation of parents). Those ‘ACE scores’ were then mapped onto the respondents’ current health status as adults.

The results were stark. Children who experienced four or more of these ACEs were deemed two to four times more likely to smoke, and four to 12 times more likely to become alcoholic or drug addicted as adults, compared to people with an ACE score of zero. Further, the study found that high ACE scores were strongly correlated with ischemic heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, and even skeletal fractures later in life. It seemed that childhood trauma wasn’t just causing obesity. It was causing all manner of addictions and health problems in later life.

Over the following decade Dr Felitti became something of a hero to mental health professionals. Helping professionals like counsellors and psychologists are almost overwhelmingly left-leaning, so Felitti’s work was well received in such circles. It seemed to vindicate their convictions that social ills like health inequality and addiction had purely sociological causes, and could therefore be solved only by direct government action.

By the end of the decade the ACE study was so lauded that organisations like the World Health Organisation were adopting the concept. In 2012, they issued their own questionnaire (the ACE-IQ) which sought to measure ACEs across the globe. The WHO noted that ACEs can ‘disrupt early brain development and compromise functioning of the nervous and immune systems.’ So not only were ACEs causing actual organic disease, they were permanently rewiring the brain. As a result, large sums of money began pouring into research which sought to isolate the specific bio-markers of adverse childhood experiences, and the idea that early life adversity might be ‘biologically embedded’ took hold.

By the 2010s the idea that childhood trauma causes physical illness began to seep its way into popular culture. Magazine and newspaper articles ran headlines linking childhood trauma to migraines, cancer, and autoimmune disease. Numerous cities across America (such as New Orleans and Baltimore) started initiatives to protect children from trauma induced brain damage. Universities and schools ran training seminars to create ‘ACE-awareness’ in their staff. In 2018, first minister Nicola Sturgeon gave an introductory speech to welcome some 2,000 delegates to the first ACE-Aware Nation conference in Scotland. She noted that ACEs can ‘affect children’s physical and mental health’ and vowed to make sure that ‘an understanding of ACEs is embedded right across our services.’ All of these initiatives cited the ACE study as their ‘proof’ that childhood trauma causes addiction, disease and mental illness.

As of 2023, the original ACE study has been cited more than 15,000 times and ‘replicated’ in hundreds, if not thousands of other studies. But few have seriously questioned its findings, or indeed the veracity of the idea that trauma permanently damages the brain. To my mind the ACE study was misleading, both in the way it presented its findings and the types of questions it asked. The results have proved to be disastrous for the mental health of our increasingly fragile younger generations.

For example, one of the ACE study’s initial findings was that a child who experienced four or more ACE’s was twice as likely to become a smoker than a child with an ACE score of zero, and that those risks climbed with additional ACE’s. What the blurb emanating from the study didn’t emphasise however, was that only a minority of people with four or more ACEs go on to smoke (13.5 per cent). Even lower rates of prevalence were observed with injection drug use and alcoholism (3.4 and 16.1 per cent respectively). Surely, if childhood trauma is the main cause of addiction, and especially injection drug use (as has been portrayed endlessly by trauma advocates such as Dr Gabor Maté, who recently gained notoriety for his televised ‘trauma-focused’ therapy session with Prince Harry) then we should be seeing more than a 3.4 per cent prevalence rate in those most effected. What this tells us as much as anything else, is that 85 to 95 per cent of traumatised children do not go on to become addicts, alcoholics, or even smokers.

The way the ACE study presented its findings wasn’t the only problem. There were multiple problems with the questionnaire itself. When we look at the wording of the questionnaire, what we find is that many of these so-called ‘adversities’ weren’t actually that traumatic at all. They were subjective, vague, and a virtual open invitation to self-indulgence and grievance. Take question one for example:

‘Did a parent or other adult in the household often, or very often, swear at you, insult you, put you down, or humiliate you, or act in a way that made you afraid that you might be physically hurt?’

This is a hopelessly wide-ranging question. Given that the ACE questionnaire was quantitative, not qualitative, respondents could only answer yes or no. So if a respondent ‘felt like’ they had been frequently ‘put down’ by their parents during childhood, they could answer yes and would then be categorised as having suffered ‘psychological abuse’.

Question two asked: ‘Did a parent or other adult in the household, often, or very often, push, grab, slap, or throw something at you, or ever hit you so hard that you had marks or were injured?’

Obviously a simple ‘yes’ leaves us completely in the dark as to whether the respondent was beaten up repeatedly by a brutal step father, or simply ‘grabbed’ on occasion by his long-suffering single mother who was fed up with him smoking dope in his room. Nevertheless, any affirmative answer scored a point for ‘physical abuse’.

Question four was particularly weak: ‘Did you often, or very often, feel that no one in your family loved you or thought you were important or special – or [that] your family didn’t look out for each other, feel close to each other, or support each other?’ Surely this is describing the majority of the planet?

As for the idea that childhood adversity is toxic to the brain, this is actually a radical claim with little in the way of real evidence. In his brilliant book The Trouble with Trauma, child psychiatrist Michael Scheeringa explains why evidence for the stress-damages-the-brain-theory is so thin on the ground. The only reliable evidence that would clearly demonstrate a link between trauma and subsequent changes in the brain, he says, would be a study that captures brain images before and after the trauma (a pre-trauma prospective study followed by another one after the event). Currently, there are very few of these studies due to the obvious fact that it is not ethical to induce trauma.

Instead there are lots of cross sectional studies. These studies look at brains after the trauma has occurred, but have no way of knowing what the brain looked like before the trauma (e.g. whether the person had an undersized amygdala, over-active pre-frontal cortex, or other neurological disability which might predispose them to a heightened traumatic response). The few before and after studies that do exist seem to point towards pre-dispositional vulnerabilities. Predisposition has also, so far at least, been the most successful theory explaining other psychiatric conditions like depression, schizophrenia, anxiety and bipolar disorder.

So the trauma damages the brain theory is the outlier here, and it is frankly incredible that governments, top tier universities, and entire professions have placed all their eggs into this big Freudian-hypothesis basket.

The reasons for this bias are fairly obvious however. Pre-disposition points to genes, a less headline-grabbing area of study, and therefore not as useful for raising funds for trendy political healthcare projects.

In the DSM-5 (The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition) trauma is defined as a psychiatric disorder (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) which has horrendous and unmistakable symptoms. These symptoms occur (in some individuals) after being exposed to ‘actual or threatened death, serious injury or sexual violence.’ Things that are certainly outside the realm of ‘normal human experience’. Psychiatrists have known this since the Vietnam war.

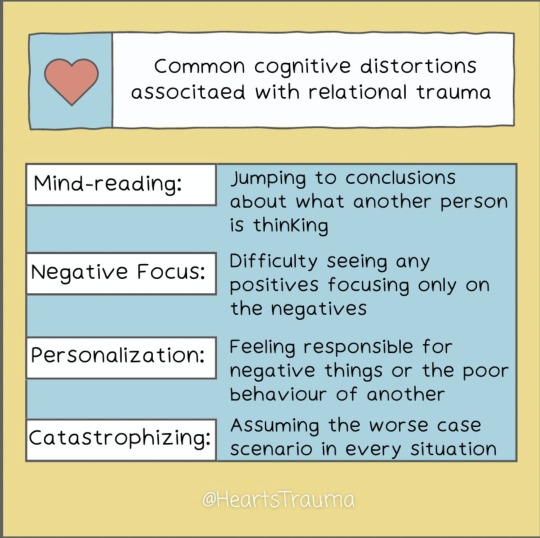

Nevertheless, since the 1990s psychiatrists under the sway of social justice politics (and bolstered by the findings of the ACE study) have been attempting to nudge a more watered-down version of trauma into the DSM. This includes ‘complex-trauma’, ‘developmental-trauma’, ‘relational- trauma’, and other snappy, made-up disorders. These ‘knock-off’ versions of PTSD have proven to be scientifically unverifiable, and have been rejected for inclusion in the DSM on multiple occasions, but nevertheless, they remain incredibly popular with clinicians and the public because they like them, and because they fit with what they believe. This concept creep around trauma is a perfect example of how bad, unscientific ideas can completely capture the zeitgeist when they peddle the right narrative.

If this politicisation of psychology is not successfully challenged, I have grave fears for what the consequences will be. If we don’t stop using the word trauma, then those who suffer from real trauma (women who’ve been raped, children who’ve been burned, soldiers who’ve been blown up by mines) will have to share their services with those who, frankly speaking, don’t deserve them. And, people with addictions and other conditions that could be turned around with the right treatment will fail, because they are being protected and wrapped up in cotton wool by health professionals who are using them to fulfil their own professional and ideological goals. This cult of trauma must be stopped.

#Alastair Mordey#pseudoscience#psychology#human psychology#trauma#childhood trauma#trauma informed#complex trauma#CPTSD#developmental trauma#relational trauma#cult of trauma#victimhood#victimhood culture#medical corruption#adverse childhood experiences#adverse childhood experiences study#religion is a mental illness

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I mean it in the way that resonates

For me,

I mean it in the way that

I feel love knowing

That there is a God who loved us all so much

That they put a little piece of themselves into

Creation.

or maybe this is the sort of

Chicken and egg situation.

Is God all of us sitting in the Mandelbrot in meditation.

All of us a fractal of the experience?

All of us thinking and feeling ourselves in meditation

Piecing the All together ?

While our hearts beat and beat and beat

Moving through each feeling .

Each lesson?

If I were to give an apology it would be like this:

You are enough.

Will forever be enough.

Any attempt to subtract from you

still results in you being wholly and fully and completely enough.

When things are added to you.

It emphasizes how infinite you are.

Because nothing can affect the whole

That you are.

What’s taken

what’s added

is an illusion of other

Yet still it comes from you

And also

Resides in you

When someone

or

something tries to trick you

that somehow they can degrade you

Your enough-ness, your wholeness…

The one sitting in meditation says

“It is a false belief system that

Got programmed into you.

imposed upon you….

But also I see the value in a lesson”

Because again.

You are,

the manifestation of God

in a human body.

Each and every one and thing of us.

God’s creation

in meditation

An acknowledgement that

you are.

And thus, forever will be

infinitely

Whole.

I see God in you

And I hate fighting

I’m disconnected enough -

Can we continue loving each other now?”

-Jheanel Brown

#personal#poems#apologies#well met#if you ever felt small for any reason#mental health#relational trauma#interpersonal relationships

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay. Anakin, attachment styles, relational trauma, anxious-preoccupied Anakin. We need to talk about anxious-preoccupied Anakin.

First, a short (or as short as I can make it) primer on what the phrase "attachment styles" even describes. This is absolutely not attachment in the Buddhist sense of attachment/nonattachment as describing ways of responding to the transient nature of all things. BUT unlike the many anti-Jedi takes I've seen, attachment in this context absolutely isn't synonymous with love, either (good GOD no!!!!!).

Attachment styles describe a common grouping of traits that characterize how a person connects to others in relationships. Each one can only really be understood in context. Typical models have four attachment styles for adults: secure, anxious-preoccupied, avoidant (subdivided into fearful avoidant and dismissive avoidant), and anxious-avoidant. The last 3 are collectively referred to as insecure attachment styles, essentially styles which arise when people don't feel safe enough in one way or another to refuse acting on conditioned survival responses.

While most attachment theory is focused on how attachment styles affect compatibility in romantic relationships, the reality is these can come out in any type of interpersonal relationship. The overwhelming amount of literature is also targeted to straight people as a default, but these dynamics are just as real (possible even more prevalent since heteronormativity exposes us to increased familial trauma) for queer people.

Attachment styles begin forming in infancy and are very difficult to change, especially as a teen or adult. It's taken me personally over 14 years of dedicated practice to get like 75% of the way there. To call it merely a habit or a personality trait would be vastly underestimating the situation.

Please do not take any of the clickbait littered all over the internet about attachment styles at face value for anything, even fiction, because it's misinformed as fuck. And please don't use this post as IRL medical advice.

Also, to get a few things out of the way: no, the Jedi did not abuse Anakin. Chancellor Palpatine sure did though. No, the Jedi did not deserve Order 66. It's literally a fictionalized Holocaust. Yes, Anakin did need care and intervention he didn't get, but also yes, the Jedi did have some form of therapy. Given our society's piss-poor track record for helping traumatized children IRL, I doubt anyone here has room to throw shade on them.

If you do feel like this post is describing you or someone you know, THAT DOES NOT MAKE YOU EVIL. It is important to remember that human beings are immensely diverse. People of any one attachment style will still relate differently based on factors like risk tolerance, culturally imposed values, varying levels of altruism and self-interest, differing triggers and stress responses, levels of introversion/extroversion, and so on. Anakin is one example of the anxious-preoccupied attachment style put in a very extreme situation, in fiction, in the context of everyone watching/writing already knowing he would become Vader.

Secure Attachment

A secure attacher is someone comfortable relating to others and navigating healthy boundaries. They can give you space as needed without feeling abandoned, give and receive support without feeling smothered, communicate effectively in close relationships, and are comfortable showing vulnerability when it's appropriate to do so. Typically, this happens when a child's caregivers hit a nice balance of being emotionally available, allowing the child their autonomy, and fostering the natural development of emotional self-regulation skills.

I would posit the majority of Jedi are likely secure, as they are given plenty of socialization in the creche, their material needs are met unconditionally, they aren't expected to care for their caregivers and they are taught to be considerate of the impacts of their choices on others. The standard of emotional self-regulation for adult Jedi is high, but they're still allowed to co-regulate and seek help from eachother.

Secure attachment is considered the stablest state and the one in which relational concerns do not present a constant source of distress, disruption, or maladaptive survival behaviours. As such, it's also the style most conducive to practicing nonattachment in the Jedi sense of the word.

Anxious-Preoccupied (AP) Attachment

Anxious-preoccupied relational habits develop when a very young child's caregivers give care inconsistently or conditionally, or in adverse conditions where a child endures extensive coercion and abnormally high levels of uncertainty from an early age. In Anakin's case, while Shmi's parenting is fine, the fact that they could be sold apart from each other at any time, and that slaves are beaten and worse at their owner's whims, was a recipe for him to develop AP attachment.

The core mechanics of anxious-preoccupied attachment are driven by two trauma-based beliefs. 1.) An AP attacher fears connection can be witheld or love taken away from them at any time. 2.) An AP attacher does not believe they will be loved unconditionally and therefore feels they need to do something or else risk being disposed of.

Since the formative experiences come from an age when abandonment by one's caregivers all but garauntees actual physical death, many anxiously attached adults do not believe they could survive or function without their loved ones, or may find the thought so painful it represents a meaningless existence or a fate worse than death.

People with the AP attachment style may stay loyal to and stay close to someone who has hurt them regardless of how severely or how many times, even if they know the person is dangerous or malicious (like Vader does with Sidious). Because they see themselves as wanted only for what they can do/be/provide/live up to, they usually live in constant fear of being replaced in favour of someone better suited to their loved ones' wants and needs.

When triggered to the most extreme expression of their survival behaviours, an AP who loves you will do anything for you, no matter how difficult or painful it is for them- and sometimes even if it compromises their own moral integrity. They can be tempted to behave possessively or act out, but are also in danger of losing their own sense of self or having their autonomy subverted.

Often, the attempt to earn love comes out as some form of intense performance pressure: achieving enough, being funny enough, pretty enough, smart enough, helpful or useful enough etc etc. Taken with all the other signs of AP attachment Anakin shows, this is almost certainly the root of his hunger for praise.

"Earning" love usually also involves hiding the perceived "unwanted" parts of oneself, things like flaws, needs, vulnerabilities (this is why many APs struggle to say "No"). They may be unable to ask for support when it's needed, or may be able to ask but only in a very oblique/vague/stifled way. AP attachers tend to get very good at shrinking themselves emotionally or performing "acceptable" reactions (i.e. appearing contented or pleased when they're actually hurting). As would be expected of a slave.

This type of appeasement is almost certainly what Anakin is doing when he shuts down Ahsoka's attempts to get him to talk about his past as a slave, when he's vague with Yoda about his Force visions, when Padme has to ask him multiple times before he can tell her what's wrong, etc. It's basically a diffuse variant of the fawn response.

There's so much more left to say here but I'll have to continue/elaborate later. I'm gonna go touch grass. Reblog to give Anakin a headpat and tell him he's a good boy.

#anakin skywalker#darth vader#sw meta#anxious attachment#anxious-preoccupied attachment#attachment styles#relational trauma#Anakin's Fall#pro jedi#pro anakin getting headpats though#give him a forehead kiss#blorbo from my therapy homework

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

today i was able to heal a little more of myself. you looked at me with fear and anxiety. fear that we will ruin, the fears i was holding too. and i did something i hadnt done quite the same before. i held myself to a higher standard. i empathised, and validated and expressed my feelings. i asked for solutions, i tried to problem solve. you tried to problem solve. you didnt say it was doomed. you didnt find ways to go. you held my hand and i held yours and we both admitted we were very broken people just trying to do right by each other. it was ugly and it was beautiful. and it was normal. and real. and i didnt cause a scene. and i held onto the fact that if someone isnt going to put the work in with me, then there's no place. and i was strong and vulnerable at the same time. i felt... like something new. what i would have been like without the trauma. i was regulated.

i was regulated and then you were too

. i realise i am role-modelling to myself what healthy communication is. and this then shows others they are capable of the same. we all deserve peace.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Are they actually sweet and caring and what everyone’s been saying you deserve or is it just love bombing again, a book by me.

#personal#personal rant#just cptsd things#emotional abuse#tw cptsd#tw emotional abuse#tw trauma#tw relationship trauma#cptsd#relational trauma

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Shadow bonds are alluring for the unhealed parts of our souls on a journey in search of connection.

Zisa Aziza

#truths89#poetry#zisa aziza#negressofsaturn#trauma#bonds#shadow#chaos#relationships#relational trauma

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why is it that they never notice?

They don’t notice you pulling away, struggling desperately to protect yourself from the pain you know they’ll inflict.

They don’t notice you losing interest in everything that made you you, in everything that has been your rock up until this point.

They don’t notice that you can’t pretend to be happy anymore, even in front of other people, even in front of those closest to you.

They don’t notice that you cry yourself to sleep every night, and cry when they aren’t looking, because if you did it in front of them, they’d mock you.

They don’t notice that food has become meaningless to you, because it doesn’t heal the aches like it used to.

They don’t notice the emotions-the rage, the pain, the sorrow, the helplessness-always mounting up in you, making you physically sick and weak.

They don’t notice anything…until it all erupts.

And when it does, they notice. And they call you crazy, unrealistic, lazy, entitled, dramatic, idiotic, and weak. And you think to yourself, maybe you are weak. Now. But you weren’t always. The burdens you’ve carried for so long have made you weak, and exhausted.

But when they see you struggling, dying under the pressure of your pain, they still won’t lift a hand to help you. Instead, they scold you for stumbling. For falling to your knees. For dropping your burden.

For seeking rest, even for just a moment. Seeking the rest that only they can provide. But they won’t.

#elissa is lonely#mental trauma#trauma#mental health#mental health support#anxiety#depression#loneliness#extreme loneliness#mental exhaustion#family trauma#friendship trauma#relational trauma

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

“What I see time and time again is after we travel together to these previously terrifying places something switches in folks. They will come in and say they were having a common experience of anxiety or panic. But this time they were not as frightened and some really cool new way of dealing with the situation arose in their consciousness. They will often say this nonchalantly, not realizing the profound magnitude of this developmental trauma act of triumph. They are experiencing, and literally giving to themselves, the missed relational experience from their history that they always needed. Usually one filled with compassion, insight, and hope.

It seems as though single event trauma and developmental trauma are different in their healing as well as in their creation. For single event trauma fairly quickly memory can be metabolized and the necessary action completed. Because of the long term and systemic quality of developmental trauma one has to live their way into a new experience.”

#an act of triumph#pierre janet#trauma#trauma recovery#dissociation#relational trauma#CPTSD#resource#resourcing

1 note

·

View note

Text

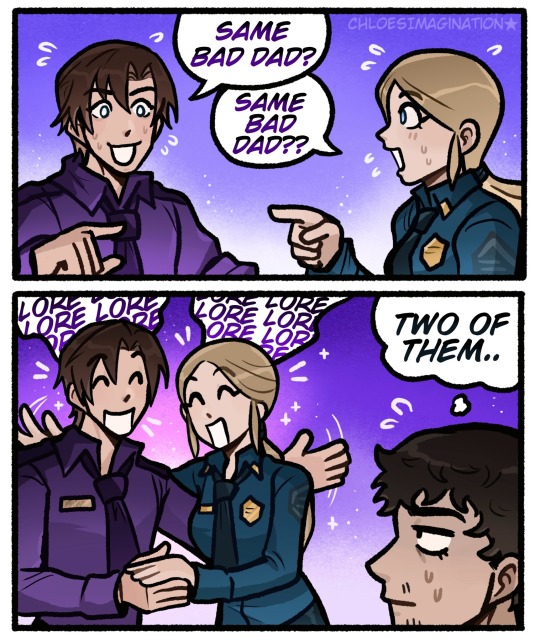

FNAF movie Vanessa and Michael would get along so well

#myart#chloesimagination#comic#michael afton#vanessa afton#vanessa fnaf#william afton#the afton family#mike schmidt#fnaf#sister location#fnaf movie#fnaf fanart#five nights at freddy's#they finally have someone to relate to on childhood trauma 🤝

29K notes

·

View notes

Text

It's crazy how trauma makes you push people away when all you want is love.

#quoteoftheday#life quotes#loveyourself#inspirational quotes#literature#wordsofwisdom#book quotes#trauma#wordstoliveby#spilled words#motivational quotes#relatable quotes#quotes

33K notes

·

View notes

Text

calling the cops on someone else in america for drug use is the most comically evil action i can think of that you can still admit to in public and (unfortunately) not be shunned/exiled/physically attacked for. you're very explicitly saying that your sheltered discomfort with seeing someone do drugs is worth ruining that person's entire life over (even though you could get the same effect by just continuing to walk past the drug user until you never see them again). 18th century dauphin mindset. "papá! papá! i espied that peasant over yonder partaking of a snuffbox! throw him in the dungeon, lest my delicate morals be corrupted any further!" kill yourself perhaps

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

Relational Trauma

Have you ever felt like your past experiences have left you with emotional scars that you just can't seem to shake off? Do you find it difficult to trust others or form healthy relationships because of past trauma? Relational trauma could be the culprit.

Find out more about relational trauma and how it may be affecting you by reading the full blog linked in our bio!

1 note

·

View note