#rpg theory

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I enjoy the Histories in BREAK!! being a mix of lifestyles. The last edition of D&D is probably the game most people have played that involved some kind of history/background mechanic, although I think we can all name some games where that's a much bigger factor. I think something that got missed in the way people treated those was that the initial PHB offerings were effectively all reasons one might travel. Even the Hermit: they lived a secluded live, discovered some secret or insight, and are out in the world now spreading that around. Over time this remained mostly true even if the became more tied to specific careers and experiences, a mix of superhero origin story and CV. In a world where you're constantly beset by giant beasts, ghoulies, magic monsters etc, the average NPC leads their life in one place.... content with their lot and awaiting a wandering party to fix their problems. When the world is wild, civilization is small. BREAK!!, on the other hand, is not terribly wild at all. There are places OF wildness, and places where time has gouged deep wounds into the world, but the world is largely known and "mapped" such that there are few places to leave blank for "here be dragons." Indeed, BREAK!!'s map indicates explicitly where there WERE dragons... What great nations and city-states exist do so with something approaching a modern awareness of one another that recalls at least the European colonial era if not late Victorian explorer accounts. Folks in Berry Town may have heard that the junkers of Stahlfield eat babies but they know where they are and what their overall deal is apart from those rumors, at least. One scholar of ancient culture I read in college had a definition of civilization as the point where a shared language is adopted, and since Low Speech is baked into the Outer World and spoken by all sapient things one could argue for BREAK!! being among the most civilized and connected fantasy settings on the market....

The Histories on offer do have some typical genre conventions (e.g. Knight Errant, Street Rat) but they're typically very specific and very tied to the demands and expectations of their associated regions. Some denote training, some denote upbringing, and some denote circumstances, but whereas I think a lot of D&D5's Background were designed from the perspective of "Why have you found yourself on the road in an adventuring party?" as if being "an adventurer" is something you can just fall into, BREAK!!'s Histories seem more designed around what your character would be doing if they weren't ON AN ADVENTURE. Tom Hanks used to be a teacher in Saving Private Ryan and that does inform his character and his behavior when you know that, but it's wildly different from how everyone in his command pictures him. He's on an adventure because of a convergence of unique circumstances, some of which arose our of necessity and some of which seem almost contrived against him. He's going to go back there some day, just like Gonzo the Great. There are others in his company who feel differently, who can't wait to leave their old life behind and use the money and experience from their military service as a launchpad into something new, something better than the circumstances they left behind.

That's because the Histories in BREAK!! represent a choice. There are some folks bopping around doing good deeds because it's what they've run towards, and there are others for whom these wonders and horrors are only something to run THROUGH. Sometimes the choices are easier than others: someone devoted to "vanquishing all evil" after a life of pious service will find being a vagabond savior a smooth, imperceptible transition. A merchant or craftsman might easily find opportunities to ply their trade during travels, or might commit to this new way of life precisely because of the opportunities it affords them for when they elect to walk away. That's life, though: depending upon our circumstances and resources, some lifestyles might make some choices easier or much much harder depending on the person.

But it is a choice. That's why they're Histories and not Backgrounds. Do you long for the Shire and wish you'd never left, or do you embrace the riches and spectacle that you've found walking man's road: your past or your present? Known or unknown? You have to reconcile it somehow to have any future worth speaking about at all.

#break rpg#break!!#break!! rpg#break!! inspiration#breakrpg#rpg#ttrpg#rpg theory#backgrounds#character history#character background#lifestyles

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

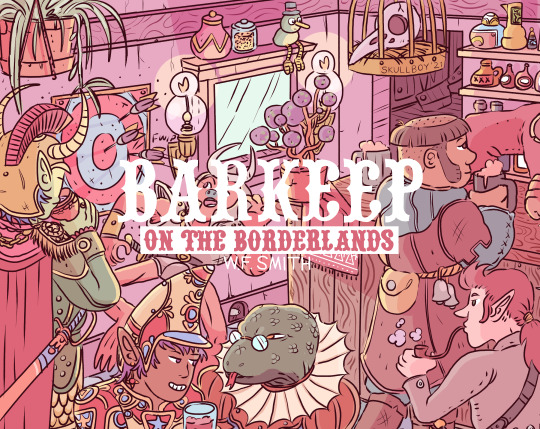

Illusory Sensorium ran a game of Barkeep and their writeup is one of the clearest signs that the hard work we put in was worth it.

Here's the recap. I genuinely was laughing out loud a few times. Highly recommend: https://illusorysensorium.com/b1-wand-of-embiggening/

If you want to delve into the design theory of Barkeep, keep reading! ⬇️

When we were working on the book, we came up with a sort of mantra for the encounters: Is it sticky? Is it toyetic? Do the NPCs have means, motive, and opportunity? Is there information, choice, and impact?

That's a lot of jargon, and it's been synthesized from across multiple sources. Prismatic Wasteland summed it all up here:

Sticky means that the encounter isn't something the characters can avoid. It sticks to them.

Toyetic came from false machine as well, but also from a post now lost to time from Rebecca Chenier. Basically—will the players and GM want to pick up and play with the encounter?

MMO is just a way to conceptualize NPCs in a simple, understandable form.

ICI is from Bastionland. We can't make informed decisions without information, and there's no point to making decisions if our choices don't matter.

Building the encounters meant looking at each of them carefully and considering those foundational elements. Not EVERY encounter needed every single thing. In fact, with the way WFS wanted to write the book, each encounter had to be relatively short and packing a punch.

A really really sticky encounter didn't need to be as toyetic, and a really fun and interesting encounter that the players would NEED to investigate didn't need to be all that sticky. Everything is a gear of a different size that turns the whole engine.

Illusory Sensorium thinks that they ran the game "wrong" and I disagree. They used the tools provided by the book and had fun! Mission Accomplished!

But one thing they point out very early on is how they "trusted" the encounters in the book as written. The very first one they got is quite simple: 54 skeletons in a conga line, labeled like playing cards.

Incredibly toyetic, not sticky. But the players immediately joined in!

They could have moved on, but that situation was too tantalizing to skip. The rest of the game unfolded from that first encounter, and was filled with shenanigans. The work we put in—hand crafted encounters—worked out!

I'm incredibly proud of the work everyone on the team put into Barkeep, from the writers, artists, and fellow editors. I'm especially proud that people are playing the adventure and having fun. People playing the stuff you've worked on and made is the best feeling as a creator.

Thanks for reading. There's a lot of links in this thread, because I love tracing the history of things. It's no surprise that blogs are the home for so many of these ideas—word of mouth and common practice are easily lost forever when not documented!

The bloggies, a celebration of rpg blogs, are happening now! I've got a post in the running, and I'd love it if you voted for it. My competition is FIERCE (and I recommend all the nominated posts as reading material!)

Vote for RANSACKING THE ROOM today!

#indie ttrpg#ttrpg#gming#rpg#blog#roleplaying#tabletop rpgs#ttrpg community#ttrpg theory#rpg theory#adventure design#adventure

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is Inspiration Goat sniffing at?

As heard on the Daydreaming about Dragons podcast, the Inspiration Goat helps me process media and take parts that are useful for the gaming table. This isn’t about the hottest new thing or the crowdfunding with the biggest payday; it is just a few geeky things that are inspiring me. It might be weekly; it might be monthly. It all depends on how fast the inspiration goat chews on media and who…

View On WordPress

#Apocalypse World#D&D#Danien M. Ford#Disney#dnd#Don Bluth#Dungeons & Dragons#Dungeons and Dragons#Evan Torner#fantasy#Fifty Years of Dungeons and Dragons#gaming#Inspiration Goat#Jay Dragon#Magic Items#Mark Brooks#Rascal#Rascal News#rpg#RPG Theory#Savvyhead#ttrpg#Workshop#X-Men#X-Men &039;97#Yes Indie&039;d Podcast

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I was Was Smol, homebrew was only for rules... I spent a few years in the '10s being routinely baffled by the questions and attitudes of other players from outside my little bubble!

(Please read this post with a tone of intellectual curiosity, not mockery or derision etc)

A D&D-ism I find kind of interesting is the assumption that the concept of "homebrew" as a distinct category of content is broadly applicable outside of like. The very biggest games in the medium.

Of course, "homebrew" mechanics are always gonna be a thing for most RPGs, because people like modifying rules to tailor their games to their specific group etc (althought to me the idea of "homebrew" mechanics implies not only a few houserules but like. A major overhaul of at least one of the game's systems). But in terms of like, content, I think the framework of a clear delineation between official and "homebrew" content presupposes the existence of both an extensively defined default setting and a wealth of official published material that most games simply don't have.

I was recently asked by a friend (through no fault of his own, this isn't like a personal failure of anything, he's a nice and smart guy 👍) if a Mausritter campaign I was preparing to run was gonna be homebrew, and in that moment it kinda clicked for the that the concept of "homebrew" doesn't really make sense to apply there. For a game like Mausritter (and other like Macchiato Monsters, The Black Hack, etc.) which at most provide some vague background info about the world (mostly in the form of random tables) and then present you with a solid toolkit to create your stuff for it, the idea of "homebrew" as a distinct category of content isn't really a useful or applicable lense through which to look at them. Short of only ever running the example adventure from the Mausritter rulebook over and over again, there is no mausritter campaign that isn't "homebrew".

212 notes

·

View notes

Text

The hard work theory of RPGs

My big RPG theory is that the purpose of an RPG book is to do the hard work for you.

RPGs are a creative endeavour and most of the fun what the players contribute. But a good RPG makes sure that the decisions the players have to make are the most interesting ones. A bad RPG offloads the work of understanding or interpreting the system on to the players and becomes burdensome to play.

A good game is helpful. It does the hard work for you and leaves the fun decisions for you and your group.

There's plenty of talk over what makes an RPG system good, but I'm going further and asserting that this principle is true for every aspect of a game.

Any of us can come up with the bones of a good setting idea in a few minutes. But if you've ever sat down and tried to write it up in a usable fashion you'll know there's so more to it than that. A good RPG has also done those not-fun bits for you. Where fiddly details matter, they've done the homework and compiled them for you. The author has made the whole thing thematically coherent, with enough detail to inspire but not so much as to feel constricting. And the author has done the hard work of identifying the most important bits, and expressing them succinctly enough to ensure that all prospective players are on the same page about it.

Because another big part of "the hard work" is finding the right game for your group and getting them to play it. A good game uses words and art to demonstrate what will be fun about it. And it presents itself honestly so that you can make an informed decision whether to play it or not.

And that's where I'll distinguish between games that are good and games I enjoy. There's plenty of good games out there I will never play because they did a good job communicating what they are about so that I know I will not enjoy them. Likewise games that present themselves as one thing, but it turns out are most fun when played a different way, are flawed (and often end up with players angry at each other for playing "wrong").

A good game shows you at the most fun way to play it, makes that as easy as possible and then delivers on the promise.

There's certain popular games (that I'm not brave enough to name), which are very unexciting by traditional metrics. Their mechanical systems are generic, repurposed (or absent!), doing little if anything in service of their premise.

But what they do do is effectively communicate a novel way to play. They do a fantastic job communicating that, how to do it and why it will be fun. They make people excited to play them, even if they'll be rolling the same familiar dice the same familiar way.

By the hard work theory, what makes them "good" RPGs is that the game book made it easy for the players play a fun game that they wouldn't have played otherwise.

This is already too many words. Suffice to say I also have strong feelings about other ways this applies to rules, settings and more.

#rpg#rpg theory#too many words#I'm sorry#I wrote this to have written it more than for it to be read.#No shit Sherlock this is so obvious why are you wasting our time VS How dare you my special snowflake game disproves your generalisation

1 note

·

View note

Text

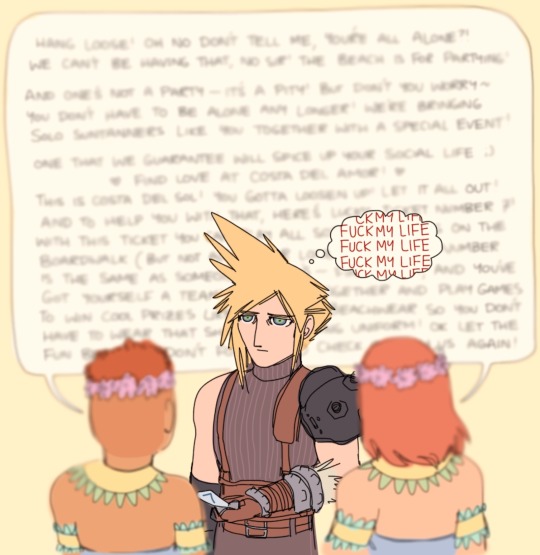

lowkey funniest part of rebirth is when cloud dissociates BIG time while the costa del amor girls are making their pitch

#this part was insane. i can't believe he held it together long enough to not fucking snap#he. literally tries to walk away from them like three times AND THEY KEEP BLOCKING HIM FROM LEAVING LMAOOO#the fucking costa ass elevator music playing the whole time#it's surreal#listen. listen#i have a theory about rebirth. that the devs are trying to flip the rpg protagonist thing around#so instead of the character being a blank slate that the player gets to shape however they choose#they want THE PLAYER to become cloud strife. you WILL dissociate with him so god help you.#they want you to suffer like you've got alien brain worms and mako poisoning in real life. this scene is proof.#ffvii#cloud strife#my art <3

629 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Batter Is One of My Favorite Video Game Protagonists Ever

News of the upcoming remake recently got me back into OFF, and as I played through the game for the first time in years, I was struck anew by just how great a character the Batter is.

Not just for his role in the subversive meta-narrative, which was fairly new in video games at the time, but also for really being just a really nuanced and fascinating character.

Now, even knowing the twist and the way the game ends, it might be tempting to write off the Batter as a one-note character, like, "Oh, he's just an uncaring thug who wants to kill everyone," but no, I think that's a very shallow read. The Batter has a lot of depth if you take the time to really look.

So, because I've been chomping at the bit to gush about my favorite character, let's go down a list of some of the character traits that make the Batter great.

1. Doesn't Give a Fuck...or Does He?

Years ago, there was a post on Tumblr (that I won't even try to find now) that said of the Batter, "Man, this guy just does not give a fuck," featuring a bunch of screenshots of him saying things like this:

Don't get me wrong, his terseness and lack of reaction to some of the game's most outrageous or even harrowing moments is hilarious in a kind of black comedy way, but to imply that the Batter doesn't care about anything is inaccurate.

For one thing, he drops the blunt speaking style and becomes very eloquent and even passionate when confronting those he sees as "impure."

That the game acknowledges him to be a figure controlled by a player by no means necessitates that he's merely an automaton, passionlessly following orders. He's devoted himself to his mission with the zeal of a fanatic. He fervently believes that he is right and just and that anyone who opposes him must be cut down for the greater good.

Confronting what he perceives to be evil is the most surefire way to loosen his tongue and get him fired up, which brings me to my next point:

2. Has a Strong Moral Center...Too Strong

The Batter's main goal may be to wipe out every living thing in this world, including all of the Elsens, but that doesn't mean he's indifferent to the Elsens' suffering. Far from it. He's actually deeply offended by their mistreatment.

In Zone 1, the Batter decides that Dedan is hostile and must be destroyed before Dedan has even had the chance to interact with him, meaning that Dedan being hostile to the Elsen is what made the Batter decide he has to die.

He also conveys a sense of urgency during the timed mission in Zone 2, as though urged by the sight of the Elsens in immediate danger. I don't remember his exact dialogue if you run out of time during this part, but I recall him saying something like, "We're too late..." which (if I'm remembering the line correctly) would show that he's motivated not just by a bloodlust for the Specters but by the need to save the Elsens' lives.

However, what makes this morality disturbing instead of redeeming is its lack of two things: empathy and nuance. While the Batter is able to understand that people being killed or mistreated or abused is bad, he isn't capable of empathizing with the victims. The knowledge that the people he's fighting so hard to save in Zone 2 are going to end up being killed anyway once he purifies Japhet doesn't give him pause for an instant. The inherent dissonance in that is beyond his ability to comprehend. He's so self-righteous that he sees each of his actions as good, even if they result in the same outcome for a particular individual as something he's trying to prevent. In simpler terms: When a Specter kills someone, it's bad and evil. When the Batter kills someone (even if it's the same damn person), it is right and just.

The lack of nuance in the Batter's moral compass manifests as a very simple worldview: Everything that is evil must be destroyed. This philosophy is key to the game's satire of morality in video games, where evil deeds and creatures are swiftly and violently punished by the main character, usually with death. By sticking to this worldview, the Batter is ignoring the nuance of the setting he's actually in. The Elsens whose mistreatment he's so outraged by don't want him to kill their leaders, and they don't want to be killed by the Batter anymore than they want to be killed by the Specters. But the Batter is so set in his worldview that he isn't willing to adjust. If the Zones operate in a way that he deems to be evil, then they too are inherently evil and must be destroyed. This chain of logic is taken to its natural conclusion when the Batter annihilates the whole world because, yeah, that's really the only way to eliminate evil, isn't it?

It may be tempting at this point to say that the Batter doesn't care about anything except his mission and punishing evildoers, but even that is oversimplifying the character.

3. Surprisingly Human

Mortis Ghost has very clearly stated that the Batter is not human, and I believe him. (Why wouldn't I? It's his game.) That being said, some of the ways the Batter reacts to the things he encounters strike me as surprisingly human.

It isn't true that the Batter doesn't care about anything outside of the mission. There is quite a lot that he doesn't care about, but he's also capable of forming opinions that have nothing to do with the mission. If you look out one of the windows in Zone 0, the Batter will say, "I think it's a nice day out," which is a line that really surprised me when I first found out about it because it's the only time I can think of where the Batter makes a positive comment about something.

There's also the way he insists on sitting in the front seat of the rollercoaster and always puts his arms in the air while on the incline. He's not obeying you when he does these things; he refuses to get on the coaster if you try to make him sit anywhere but the front, and there's no button prompt or anything to make him put his arms in the air; he just does it.

I also love his reaction to the "Panic in Ballville!" comic in the Room.

Not only is he decidedly unimpressed with this comic, he also refuses to read it again if you try to make him. Whether he realizes the implications of his own resemblance to the villain in the comic is unclear, but his refusal to even look at it again means that he might. Regardless, moments like these show that the Batter is more than just a single-minded puppet. He does have opinions and won't hesitate to put his foot down if you try to make him do something he doesn't want to do.

He's even capable of being taken aback, as Enoch's dialogue about the Specters being the souls of the dead appears to give him pause.

That brief moment is the only one in the game where the Batter shows any sign of hesitancy or uncertainty in what he's doing. He was very convinced up until this point that the Guardians were controlling the Specters (despite Dedan accusing him of the same thing in Zone 1). Not only that, but he's never taken the time to think about what the Specters actually are. I kind of interpret this as a rare introspective moment from the Batter, where he begins to realize there might be aspects of this situation and what he's doing that he hasn't considered.

However, he quickly recovers from this moment of doubt and hardens his resolve to eliminate Enoch because of his...

4. Unshakeable Faith...But in What?

A lot of the language the Batter uses to describe himself and his mission contains a lot of religious overtones, with adjectives like "holy," "sacred," "righteous," etc. His perception of his himself matches with portrayals in the Old Testament of God as a punisher of evil and a smiter of the wicked.

I don't think I need to list all the references to Christianity throughout the entire game because that would take way, way too long. Needless to say, everyone has noticed the religious motif in this game, and when an Elsen in Zone 1 straight up asks the Batter if he's religious, he doesn't deny it.

However, I don't think it would be quite right to call the Batter a Christian. While he uses a lot of language that's reminiscent of Christianity, his dialogue doesn't contain any references to specifically Christian practices or beliefs, such as Jesus, the Bible, the saints, angels, baptism, the Resurrection, etc., etc. The Batter may have devoted himself to his mission with a religious zeal, but is the mission alone all he worships? The kind of faith he exhibits is usually that associated with a deity.

Identifying the "who" at the center of the Batter's worship is not easy. When the same Elsen from Zone 1 asks who sent him, the Batter straight up says, "Nobody." I've seen it suggested that the deity the Batter "worships" may actually be the player, but I don't think that's right either, since he's pretty quick to turn on you, without any sign of hesitation or angst, if you side with the Judge in the final boss fight.

But I have another theory. If we're still using Christianity as a reference, then the Batter would presumably be worshipping some sort of creator deity. Who is the Batter's creator?

When the Batter meets the Queen, she tells him to go back home. His response?

He outright refers to Hugo as his father. As you may recall, "Father," is one of the aspects of the Trinity (Father, Son, Holy Ghost.) The Father is God the Creator, God the Progenitor, God the Origin of the World. This, I believe, is how the Batter sees Hugo.

Remember how the Queen attacks the Batter by saying, "You don't even know his first name"? Could that be because the Batter only knows Hugo as "Father" and not any other name?

This revelation becomes even more enlightening (and disturbing) when you take these lines into consideration:

What does the Batter see as the Queen's only important role? To care for Hugo. Why does the Batter feel compelled to complete his mission? Because of Hugo. Why did he come all this way? To see Hugo. Where is his home? With Hugo. Everything is for Hugo.

That the main goal of his mission is to kill Hugo fits the mold in a twisted way. After all, Christianity rather famously centers around a God who died. That death is believed to have saved the world.

Regardless of how exactly he came to that conclusion, the Batter truly believes that killing Hugo is what's best. Even his infanticide (patricide?) is driven by his twisted devotion to Hugo, his creator and his God.

All of this is why the Batter is my favorite character in this game and none of the others (as great and memorable as they are) can even come close. He's not just a brute in a baseball costume. Each time you peel back a layer of his motivations, you only see more layers underneath. He's an incredibly rewarding character to analyze, and I never get tired of talking about him. He's a fanatic, a devoted apostle, a self-righteous murderer.

And he always sits up front on the rollercoaster.

#off game#mortis ghost#the batter#analysis#character#rpg maker#hugo#vader eloha#dedan#enoch#elsen#reposted from reddit#theory

273 notes

·

View notes

Text

I mean, Dispel Magic isn't Dispel Clockwork, so I could see an argument for Knock not working on a proper mechanical lock (albeit not with it having a history of slamming open doors that would otherwise require The Rock's intervention).

While I think later editions of D&D have carved out a justified niche for the Thief/Rogue as an archetype, as a class it still feels weird in the context of the original game. Many people, myself included, have articulated this before, but the sort of funny implication is that a class whose abilities include moving silently, picking locks, and hiding in the shadows suddenly carves out a big piece of the fictional space and says "so none of the other classes can do these things."

But I feel there is another way to look at it: instead of looking at it like "oh, the thief class locks out the other classes from having access to certain tools," it can be viewed from the angle of "the thief class creates a bunch of new obstacles, and then hoards all the tools for overcoming those obstacles onto itself."

Locked doors are the best example here: the original edition of the game in those three little brown books was, at the end of the day, a complete game. A party didn't need a thief to pick locks, because doors were not generally locked; they were stuck, and needed to be forced open with strength (and then spiked open to prevent them from swinging shut behind the party). The only mention of locked doors is within the context of the knock spell which. Yeah that's actually a fair cop, the knock spell is also a solution looking for a problem, because the existence of a spell that opens doors locked via magic necessitates the existence of doors locked via magic. But the spell opens other things, including (probably) those aforementioned stuck doors, so at the very least it has multiple use cases.

But yeah that's the thing: the original game didn't have mundane locked doors and thus it didn't require a party to have a character with a set of mundane lockpicks. What the Greyhawk supplement created was a situation where there now was a guy with a set of lockpicks who could use them to open locked doors some of the time. So now the dungeon needed to have locked doors.

#i like knock only working on arcane defences#but then again i don't think thief/rogue really exists in a viably distinct space compared to the other classes#so i guess this was all kind of irrelevant#time to go and write Dispel Clockwork i guess#rpg#rpg theory

540 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dungeon Meshi: The RPG

#Dungeon Meshi#laios touden#marcille donato#chilchuck tims#senshi#animation#game dev diary#Please give a huge hand to my coding partner#who labored for over two weeks to figure out how to implement reaction animation for the battle icons.#You may also notice that I updated the battle portraits from my previous post! New and (mostly) improved!#The death screens were not changed because I didn't think they'd get used for this video.#But Chilchuck getting one-shotted and leaving due to this being outside of his pay? Accidental comedy gold.#The full sprite (I didn't realize the bottom third would be hidden) says: “NOT PAID FOR THIS”#And yeah he's smoking. He gets a smoke break as part of his contract. Let a guy have his vices. He's teetering on a divorce.#Dungeon Meshi would be a fun rpg in theory but it would need to have immersive mechanics like cooking and foraging.#And hunger and fatigue and other status effects.#A slightly more lighthearted fear and hunger sort of game.#But that is for some other fan to do. This is just a fun tech demo for us to learn RPG maker!#So...with this mini-project concluded#we now have a foundation we can pass over to our actual game!#Next game dev post will be some game assets (probably busts and battle icons for the main party)#And after that! Most likely some more sprite sheets (I have made a few more since my first attempt)#Thank you for everyone who has been rooting us on since I started talking about this project. It means a ton B'*)

977 notes

·

View notes

Text

Styles of Prep - Games that Care

Yet another of the lies that Wizards of the Coast has sold TTRPG players, which they've bought into wholeheartedly, is that there are different styles of preparation, and all are valid for every game (because both are valid for D&D, and D&D is right for every game, of course.)

I'm gonna go over a couple games I've run, and explain that actually they all care about the type and level of preparation the GM does.

Indie games are often honest and open about what they want. To take a high-prep example, I recently ran Eureka: Investigative Urban Fantasy. It is not subtle! In the narrator section, right after the introduction, it says "We cannot advise you strongly enough to use prewritten adventure modules". It's not just there - throughout the rules, there's an emphasis that the situation, the state of the world at the outset and thus at every time that follows, is known and rigid. Eureka is a mystery game - the who, what, how, why, and more are all set in stone. The narrator is forbidden to change the scenario on the fly.

Eureka is very forceful of this because the authors, writing a game for mystery investigations, are well aware that it's damn near impossible to make a coherent mystery up on the fly. I'm sure they've tried. I've tried. It's impossible. Something will contradict, and you won't notice until well after the players have reasoned from that contradictory information. It can be done, but not well, and the mental load on the GM is going to kill them.

It's not a genre thing - Eureka is a game about the act of solving mysteries, but so in Brindlewood Bay. I don't have experience with Brindlewood Bay myself, but I do know that the GM doensn't have a real mystery ahead of time - there's a move which is rolled to determine whether a theory is correct. Both are mystery games, but they approach them differently - and each makes a vastly different demand of the GM's preparations.

On the opposite end of the spectrum from Eureka, more in line with Brindlewood Bay in fact, is just about every Powered by the Apocalypse game. Apocalypse World is very clear about what to prepare, and it's more or less the opposite of Eureka: "Daydream some apocalyptic imagery, but DO NOT commit yourself to any storyline or particular characters."

The rules actually tell you to start on what would typically be 'prep' during the first session: "Work on your threat map and essential threats". It's more like note-taking, at that point, just placing the names of stuff that gets mentioned in the session. After that first session, and between each other, you do some real out-of-session work, solidifying the notes you made into Threats.

I won't go into it at length, but Dungeon World is much the same - though there's no 'map' for threats, as characters are expected to be far more mobile, the system of solidifying problems that were mentioned in-game into problems with some mechanically attached descriptors is much the same.

Now, on to the elephant-sized dragon in the room - Dungeons and Dragons. The game itself is, truthfully, quite honest about this. It's the marketing team and the community, having fallen for their propaganda, who pretend low-prep is a valid way to play Dungeons and Dragons.

The 2014 DMG, correctly, focuses on prepared play. It asks DMs to consider "Do you like to plan thoroughly in advance, or do you prefer improvising on the spot?", but everything in that book is either rules text or preparation guides. Mostly the latter.

D&D, as it has existed since 3rd edition, (this is what I have experience with - I can't speak to earlier editions, except to note that there are alot of modules in their time and in the OSR tradition) is a game that thrives on prep. Even if that prep is procedural - tables of encounters and wandering monsters for an area, for example - it's impossible to run the game from nothing, without a lot of background, and have it work.

Imagine not knowing D&D, at all - you pick it up, read the non-list rules (so skipping most of the classes, races, spells, feats, backgrounds, weapons, etc) in the PHB and DMG, and try to run a game entirely improv from the rules and vibes. You'd quickly end up scouring the monster manual for appropriate encounters - and the game, by the rules, demands appropriate encounters! There's a budget system! It's a game about killing monsters and does a lot of math to try and make sure it's challenging without killing player characters.

D&D, at least in the books, is pretty honest about what it wants from preparation. It wants a lot! The playerbase pretends otherwise, but they're wrong. I've yet to find another game that tries to lie like this. Eureka wants you to use modules. Apocalypse World wants you to wing it. I have yet to find any game that actually doesn't care.

#ttrpg#forlorn essays by plushie#ttrpgs#indie ttrpg#indie ttrpgs#D&D#D&D 5e#dungeons and dragons#dnd#dnd5e#apocalypse world#pbta#indie rpg#tabletop games#tabletop roleplaying#eureka#eureka ttrpg#ttrpg prep#ttrpg theory

200 notes

·

View notes

Note

Doesn't the existence of MONIST-1 and MONIST-2 Imply the existence of a MONIST-0?

Normally I'd say no, because enumeration systems that are meant to be read by humans almost always label the first item as 1. 0 is meant to represent an absence of items, and enumerating an item as 0 will feel instinctively unintuitive to a lot of people.

The main reason you would enumerate from 0 is because you're programming and your integer space always starts there (00000000 for an 8-bit register, 0000000000000000 for a 16-bit register, 00000000000000000000000000000000 for a 32-bit register, etc.).

However, MONIST-class entities are reality-warping higher-order lifeforms that seem to warp not only the laws of physical reality but also of information. RA/MONIST-1 appears to have been created/manifested/summoned/revealed simply by the Five Voices thinking about it.

Consider this: it might be quite important for information preservation that MONIST-1 is always assigned integer 00000001 in any 8-bit register that refers to them, MONIST-2 assigned integer 00000010, and so on. This would suggest that 00000000 is the unique identifier of a dummy entry, padding to ensure that MONIST-1 and MONIST-2 get the correct reference number.

But the problem when you're dealing with psychoactive higher-dimensional entities is that if you joke "there is no MONIST-0" long enough...

223 notes

·

View notes

Text

Side Quest: Cozette's Decision

#mario#luigi#mario & luigi brothership#connie mario#cozette#m&l brothership#mario & luigi#m&l rpgs#m&l#brothership#mario and luigi brothership#mario fanart#poor cozette and connie man :(#really wanted the atmosphere to be emphasized with this one#this is after reclusa showed up so mario is pissed tf off#like seriously i wish we could get more detail on cozette because i have a lot of theories#wanted connie to look extra sad and like a close up so i gave her pupils#thank @yoyosdoodles for being a genius when it comes to concordian eyes

144 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any suggestions for a "normal" Gorgon build?, AKA they murder anything that dares hurt their babies

// You poor, poor bitch // Stay a while and listen.

// You do not know the horror you have just wrought. // RA have mercy on you.

// To start, make sure you have a Gorgon // I'm telling you what you should have by LL12 // Oh and keep in mind: // I haven't tested this, // This is the Gorgon I'm currently building. // FYI: This is assuming that you'll be running the same LCPs as me.

// Licenses:

Gorgon L. 3 Hydra L. 2 Tortuga L. 2 Nelson L. 2 Raleigh L. 2 Drake L. 1

// You'll call me a hypocrite for getting so many IPS-N licenses // But I don't care. // Mech Skills:

Hull: 6 Agility: 0 Systems: 6 Engineering: 2

// You wanna prioritize being an absolute tank // Because you'll be taking damage // so your babies won't have to.

// Core bonuses:

Fomorian Frame (Size 2 to 3, no pushed around) Reinforced Frame (+5 HP) Universal Compatibility (Bonus to Core Power system) The Lesson of Held Image (Or whatever you want, dump slot)

// Talents:

House Guard L.3 Drone Commander L.3 Orator L.2 Spotter L.2 Legionnaire L.2 Skirmisher L.1 Exemplar L.1 Tactician L.1

// Equipment:

Flex Mount 1: Missile Rack Flex Mount 2: Missile Rack: Main Mount 1: Catalytic Hammer w/ Thermal Charge Mod Main Mount 2: Vorpal Gun (Obviously)

// The gist is that you use the missiles at range // The hammer when they're up close // And the Vorpal Gun when your babies are hurt

// Systems: 15 Total

2 on Thermal Charge 1 on Personalizations 2 on //Scorpion V70.1 3 on "Roland" Chamber 2 on Tempest Drone 2 on Argonaut Shield 3 on SCYLLA-Class NHP

// Your whole goal is to use the Tempest Drone for area denial // While keeping your babies close to you so that your hammer can smack whatever gets close enough to hurt them, using Rolands and Thermal Charges to get as much damage as possible on every hit // While using the Vorpal to target anything that hits your babies from a distance // It relies that you stay at a medium distance // But you have the health to tank a lot of attacks

// REMEMBER: Structure is a resource! You don't have 37 HP, you have 148!

#lancer#lancer meme#lancer rpg#lancer ttrpg#lancerrpg#gorgonlove#lancer horus#horus gorgon#lancer gorgon#lancer memes#lancer build#ooc: I have no idea if this will work#I'm currently building this one out in practice#but in theory it looks good#if I missed anything#ask me about it in the notes or send me an ask again

165 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sorry if it's a silly question, as I'm still reading the book and haven't gotten to the full scope of the Narrator's job yet, but how 'long' are Eureka! games designed to go on for in-world wise - and more importantly, how alive are Investigators supposed to stay, generally? For context: I'd like to do multiple smaller investigations that are part of a larger conspiracy, individual mysteries that may fail or succeed at being uncovered, that give out pieces of what's actually going on. And, because progression (level-ups, new toys/weapons, etc.) are a big part of what appeals to my players, I think they'd prefer to keep their characters relatively alive to enjoy the benefits, and not replace them through multiple investigations. Is Eureka! able to be played like that? A broader campaign with "meta"/character progression for not being brash and getting yourself killed?

Like most TTRPGs they are billed as “highly lethal,” the truth is that Eureka: Investigative Urban Fantasy is really more “potentially lethal.”

Every character has 5 Penetrative HP and they die instantly if this hits 0, and any bullet deals 4 Penetrative Damage. The most common handguns in Eureka are capable of firing up to 4 bullets in a single action, so yeah, PCs can die pretty easily. They can also kill pretty easily, and it is up to them, not the GM, to make sure they don’t get killed.

Despite this, having played Eureka myself about... 15 times maybe? I have never once personally seen a PC death.

A good number of PCs have died in other people’s Eureka games that I know of, but off the top of my head it feels like around a third of those were killed by other PCs.

The thing is, when the players know the game is lethal, and the PCs know what they’re doing is dangerous, they both tend to be very careful, and a good lethal game will provide lots or mechanics that allow PCs to mitigate the danger. For instance, Eureka is primarily about investigation. The chances that the PCs will get involved in a shootout in any given session is very slim. Most Eureka adventures end up having between 0 and 2 instances of violent danger across the entire adventure. Additionally, that combat is mechanically deep. It is this depth that allows the PCs to make smart and informed decisions that make them less likely to die. For instance, cover mechanics and incremental range penalties that make those 4 bullets each a lot less likely to hit.

As for in-world length, that really depends of course, but we find that many of the game’s mechanics are best suited for adventures that last about 2-14 in-game days. The stuff that characters do in Eureka is usually a short, but extraordinary period of their lives.

That doesn’t mean that they can’t return for another aventure later, it just means that if you’re going to try to run a real big mystery, running it as several smaller mysteries is definitely the best way to do it. Just make absolutely sure that no one of those smaller mysteries needs to be solved or completed a certain way, or in fact needs to be be completed or solved at all, for anything about the larger mystery to work. In Eureka, success is never a guarantee.

This is a good thing, because it means that accomplishments are real, but also, Eureka is deliberately set up so that there’s entertainment value in seeing the PCs involve themselves in and be affected by the mystery, regardless of if they succeed or not, or even if they survive.

Another thing that you as GM I’ll need to do to run this kind of campaign is to make sure you know ALL the facts of the mystery before it starts. This is not something you can make up as you go along. This doesn’t mean coming up with the plot or how the PCs will solve the mystery, in fact you as GM shouldn’t interfere with that all, but you need to know exactly what the bad guys have done, are doing, and will do, and what evidence their doing has left behind. This means you’ll be prepared for whatever the PCs start snooping about, and if they do ask a question you didn’t anticipate, you’ll be able to answer from a place of knowledge informed by the existing facts you did write, rather than making something up completely.

#eureka#eureka: investigative urban fantasy#eureka ttrpg#indie ttrpg#ttrpg tumblr#ttrpg community#rpg#ttrpg#tabletop rpg#ttrpg design#ttrpgs#indie ttrpgs#roleplaying game#rpgs#urban fantasy#conspiracy#conspiracy theories#mystery#investigation#tabletop

100 notes

·

View notes

Note

There are a lot of games simpler than D&D in terms of maths and essential principles. So I got to wondering why anon with dyscalculia finds it relatively simple. Possibly it's because the other games they have come across have been more complex ones - in which case I theorise that they like meaty dungeoncrawly combat sorts of games. I was stumped thinking what makes D&D stand out in that genre besides popularity and then it hit me from something @thydungeongal posted recently. The mechanics are GM facing - a player in D&D, for example one that is still learning and has dyscalculia, can describe what they want to do with a decent sense of if their character is good at that sort of thing, roll a single d20, tell the GM the number on the dice, and get told what the resolution is. I can easily see how that helps someone get through the learning stage and get comfortable with a relatively complex system. Something with player facing mechanics is a lot more difficult for a learner with dyscalculia even if those mechanics are simpler or have fewer exceptions.

You do of course understand that the reason most people prefer DND 5E is that it's one of the easiest systems to learn? Like I'm sorry it's all well and good to 'break up the cultural monopoly' but I have Dyscalculia and DND is seemingly the only tabletop system that doesn't consistently ask me to do a hefty amount of complex math. I've never given WOTC a penny but the reason I've primarily played 5E over basically everything else is it's the only system that was extremely easy to learn and completely self explanatory. (Also - I like elves and magic and shit.) You roll one dice to see if you can do a thing, you add whatever your plus or minus is, and then roll damage where appropriate. Easy. Meanwhile seemingly everything else is like "Okay so you roll two dice except sometimes it's four and then you take this stat and you divide it by that dice roll and then you add a number equivalent to the day of the week unless it's a leap year then you times that by three and if you get a prime number you can lift that coffee cup." Like have you ever heard of Villains and Vigilantes, for instance? It's fucking insane. Like I'm not saying I don't get why you wanna make this point? But I feel like I have to point out that most people who make indie TTRPG's don't seem to focus on accessibility when designing their systems and they are EXTREMELY intimidating for new players. And often, what people who are big into TTRPG's do is assume that because THEY fully understand this system and how it works, new players will too just as easily. The amount of times I've spoken to a GM, said "This sounds a bit complicated", and they've gone "No no no it's easy" and then described the most complicated set of rules I've ever heard is ridiculous.

Okay it sounds you've had a very narrow range of experiences with RPGs then because D&D 5e is on the higher end of complexity when it comes to RPGs and most indie RPGs are actually a lot less complex than D&D 5e. Like, Villains & Vigilantes is not the median when it comes to RPG complexity. There are systems even lighter than D&D out there. :)

1K notes

·

View notes