Trans/non-binary historian. My main areas are LGBT+ history and modern British politics. Devout autist and diagnosed Quaker.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Link

My latest article on the history of Kim Jong-il’s strange Godzilla knock-off.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

UMD Video: A History of film on the PSP

The 1990s through to the early 2000s was a frantic time in the development of portable media devices, from mini TVs to CD and cassette players, and of course phones, MP3 players, and video game consoles. By 2010, consumers could take entire libraries of media content wherever they went. Movies and TV shows, however, were relatively late to the party, limited by large file sizes and the bulkiness of laptops and portable DVD players at the time.

Various attempts were made in the late-nineties and early-noughties to bring affordable video-playing devices to the market, including the VideoNow unit that would play kids TV shows in black-and-white. In 2004 Nintendo entered the market in collaboration with 4Kids Entertainment in the form of GBA Video: cartridges that stored episodes from children's shows and even a few movies for playback on the Game Boy Advance. The quality of the footage wasn't great, however, with GBA Video playing in 240x160 resolution—and with a chugging frame rate. Sales weren't great and the format didn't catch on.

Nevertheless, GBA Video did prove that distributors could use the existing install-base of portable game consoles to sell more than just games. Console manufacturers were beginning to realise this too—Nokia's N-Gage was a phone/game console cross-over that could also play video and music, while Nintendo's DS line of devices were marketed as digital planners and cognitive training tools as well as gaming units. Sony, meanwhile, had experience in the multimedia game with their PlayStation 2 home console. The inclusion of the ability to read DVDs was a major coup, giving Sony a big edge over competitors like Sega's Dreamcast.

With the success of the PS2, it was perhaps only natural that Sony would try to replicate this multimedia magic when they entered the portable console space with their PlayStation Portable, launched in December 2004 in Japan, March 2005 in North America, and September 2005 in Europe. Of course, a properly portable device was never going to be big enough to support DVDs, so they had to develop a brand new format that was up to the task. Sony's solution? The Universal Media Disc, or UMD.

***

UMD is a proprietary miniature optical disc format that can hold 1.8GB of data. It came encased in a plastic shield to protect it from knocks and scratches, and was only ever used for the PSP. When the PSP was revealed during Sony's press conference at E3 2004, Kaz Hirai, President and CEO of Sony Computer Entertainment America, stressed that Sony saw this console as a multimedia platform, and that the UMD would support full-length films, branded as UMD Video, as well as games. Trailers for Spider-Man 2 and Final Fantasy XII: Advent Children were shown playing on a PSP unit, and when the US launch date came, the first 1 million PSP Value Packs (priced at $250) contained a Spider-Man 2 UMD. Masa Chatani, Chief Technology Officer of Sony Computer Entertainment, expressed great enthusiasm in media interviews, saying: 'In the U.S. We have already met with the major studios. They pretty much love the PSP and the quality of the UMD.'

Sony announced an initial UMD price range of $19.95 to $28.95, with the lower range applying to movies previously released on DVD, and the higher range for new films launching on UMD and DVD at the same time. Each UMD would contain the full-length movie encoded in 720x480, the same as an average DVD, but this would be scaled down to 480x272 when playing on the PSP's screen. Due to storage constraints (the average DVD could hold 4.7GB of data to the UMD's 1.8GB), special features such as deleted scenes and 'making of' reels would often be completely absent. And unlike PSP games, UMD Videos were region-locked.

Despite these limitations, early signs were encouraging for UMD Video. Within a few months the format could boast 70 available titles in the US and over 500,000 overall sales. Available titles grew to over 200 within half a year, including pornographic titles in Japan, encouraged by the PSP's own strong sales. Two movies released by Sony Pictures, Resident Evil 2 and House of Flying Daggers, passed 100,000 sales within a month—whereas the first DVD to pass that mark, Air Force One, took 9 months. Sony UK chief Ray Maguire said in October 2006 that Sony was 'pretty pleased with UMD,' commenting that it had 'a fantastic attachment rate'.

***

It wasn't long before cracks began to show, however: and that isn't just a reference to the UMD casing's tendency to break, rendering the disc unusable. Film studios and retailers started to express concerns about the format's long-term sales performance. In the US, Wal-Mart and Target had already begun pulling away from UMD Video in early 2006, while anonymous executives from Universal Studios Home Entertainment told the Hollywood Reporter in March 2006: 'It's awful. Sales are near zilch. It's another Sony bomb, like Blu-ray.' An executive from Paramount similarly said of UMD: 'No one's even breaking even on them.' In response to such criticism, Benjamin Feingold of Sony Pictures Home Entertainment blamed the disappointing sales on people ripping DVDs and then playing them on PSP via the SD card slot.

Sony began teasing an adapter to play UMD on television, and the company continued to show public optimism about the format even as major studios and retailers pulled the plug entirely. PSP senior marketing manager John Koller told Pocket Gamer in June 2007 that: 'The future of movies on UMD is great. We saw a 35 per cent growth year-on-year from 2005 to 2006, which clearly demonstrates a growing interest.' Significantly, sales in Japan had jumped tenfold following major price-cuts. Koller said this was also the result of movie distributors 'calibrating' their UMD offerings to target the PSP's primary user base: males under the age of 25. This helps explain the composition of UMD Video's library, which is heavily weighted towards action, sci-fi, and comedy films.

Despite the positive signals coming from Sony, from 2007 things started to get quieter on the UMD Video front. In part this was down to the industry's growing focus on digital distribution, and while Koller insisted that the digital pivot did not spell the end for UMD, in 2009 Sony launched the digital-only PSP Go model. And, of course, the company scrapped UMD support altogether for its next portable console, the PlayStation Vita.

Nevertheless, the UMD Video library continued to grow steadily. The most complete list online counts over 650 video discs, but the list is missing many known entries, and the real figure may be more in the region of 800. When compared to the 36 cartridges released for GBA Video, UMD Video looks like a runaway success, with far greater support from third parties and a much more diverse library including action films, comedies, TV shows, anime, live music concerts, cinema classics, Chinese hits, horrors, and yes, adult films. All three Matrix films and all eight Harry Potter films were released as UMDs, along with numerous Batman movies, Academy Award-winning masterpieces like Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, and episodes of popular TV shows such as Doctor Who. ***

Sony Pictures released its last UMD Video discs in 2010, and the final releases overall came from Warner Home Video in 2011 with a full 8-UMD Harry Potter box-set. And with that, so ended the last major attempt at a game console-specific proprietary video format. With so many easy ways to watch video content in our hands today, it is very unlikely that we will see anything like it again.

These discs haven't yet become a major focus in the collecting world, but there are reasons to believe that might change. In 2018 UMD Video entered into the top-10 most-contributed formats on Filmogs. And as the noughties become more distant and the PSP becomes a 'retro' console, I suspect UMD Video will take its proper place as both an interesting oddity and a genuinely intriguing piece of media history.

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

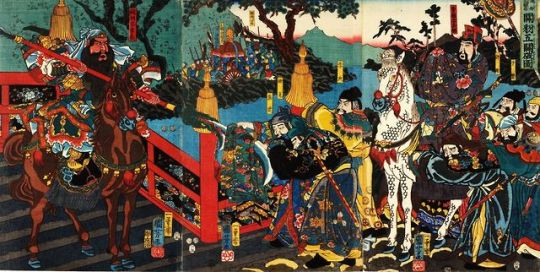

A beginner's guide to Romance of the Three Kingdoms

Romance of the Three Kingdoms is among the most widely-read and influential novels in the world, bringing together centuries of accumulated folk tales and popular elaborations relating to the Three Kingdoms period in ancient China (220-280 AD). The amalgamated version we read today is usually attributed to the fourteenth-century playwright Lo Kuan-Chung. Later editions added to this work, however, and by the seventeenth century the most widely-circulated version had acquired the immortal opening line: 'Empires wax and wane; states cleave asunder and coalesce.'

Partly because the book relates to such an omnipresent phenomenon as the rise and fall of states, it continues to capture imaginations on a global scale. Chinese and Japanese culture has drawn heavily on the themes and lessons of the Three Kingdoms in poetry, artwork, theatre, literature, and politics. In China, the novel has been adapted into multiple serialised television programmes, as well as a string of blockbuster films. Japan has developed many video games based on the book, and the British studio Creative Assembly also released their own Three Kingdoms strategy game.

For the casual reader, however, the book can present a bewildering challenge. The most popular English edition tops out at 1,360 pages, despite being heavily abridged. Following all the countless narrative threads from start to finish requires multiple readings, especially as some of them seem insignificant at first. The reader is also given a dizzying list of names to memorise, including geographical locations and, for individuals, as many as three different names which may be used interchangeably. The writing style is also not what most Western readers will be accustomed to: for example, detailed descriptive passages are used sparingly, and much of the scenery is not described at all. It is a shame for this remarkable story to go under-appreciated for such superficial reasons, but it does require some demystification. So what, exactly, is the book all about, and why does it still matter so much?

***

Until the end of the Qing dynasty in 1912, China was ruled by a millennia-long succession of imperial families. The history of the country is usually split into chunks named after the dynasty ruling at the time, such as the Zhou (1050-256 BC), the Han (206 BC-220 AD), and the Tang (618-906 AD). Each dynasty ascended to power after a period of upheaval and civil war, and ended in the same fashion after descending into weakness, corruption, and inefficiency. This process gave rise to a sense of inevitability and a feeling that all regimes have a limited lifespan—hence the inclusion of the line 'Empires wax and wane' in the edition that was circulated shortly after the fall of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644 AD).

The events of Romance of the Three Kingdoms take place during and after the demise the Han dynasty, which succeeded the short-lived Qin dynasty (221-206 BC) and before that the Zhou. The influence of Confucianism, a deeply hierarchical, patriarchal, and ritualised philosophy of social order formulated in the time of the late Zhou dynasty, can be felt throughout the Romance. Women, for instance, only become key actors when they are used as pawns to seduce enemies and destabilise states, or when they attempt to meddle in politics and thereby doom their own cause. All main characters have a deeply hierarchical view of the world, and among their followers, loyalty and sacrifice are the most prominent virtues. Nowhere are this themes more visible than in the opening chapters.

Readers are presented with a Han state that, through decades of misrule, has fallen into chaos. Instead of listening to learned advisers, recent emperors have let power fall into the hands of a group of eunuchs, leading the Heavens to inflict natural disasters and supernatural events upon China, and a visitation by a 'monstrous black serpent' upon the emperor. This sets the tone of the whole story: real events interspersed with fantastical elaborations and dramatised innovations.

We hear from one of the emperor's ministers, who informs him that the recent happenings were 'brought about by feminine interference in State affairs'. The social order has been neglected, leading to a general decay in the moral standing of state and country. Into this power vacuum comes a popular rebellion inspired by a mystical movement: the Yellow Turbans. The causes, composition, and objectives of the rebellion are left unexplored, and for the authors these details are inconsequential anyway—it merely serves as a narrative tool to demonstrate the extent of government weakness and set the scene for the introduction of the tale's central heroes.

The Han government puts out a call to arms to defeat the Yellow turbans, and among those to answer the call is Liu Bei, a shoemaker who claims descent from the Han royal line and, together with his sworn warrior-brothers Guan Yu and Zhang Fei, goes on to found the Shu-Han state in south-western China—one of the Three Kingdoms. Liu Bei is the character with whom the authors seem to sympathise most, being portrayed as an empathetic and just ruler who surrounds himself with able advisers and noble warriors. His virtue, however, often becomes a detriment when competing with less scrupulous opponents.

Another to answer the call was Ts'ao Ts'ao, later the founder of the kingdom of Wei in northern China and an altogether more ruthless, cunning, and suspicious character. Although he takes on a villainous aura at times, his state would prove to be the base from which a new dynasty was ultimately founded.

The Yellow Turban rebellion is successfully defeated by this coalition, and the eunuchs too are deposed from their over-powerful position in the royal court. Into the power vacuum, however, comes another menace, Dong Zhuo—gluttonous, cruel, barbaric—who seizes possession of the young emperor Xian and therefore the levers of power. Another coalition of regional warlords, including Liu Bei and Ts'ao Ts'ao, is formed to challenge Dong, and at this point we meet the family behind the third of the Three Kingdoms—Sun Jian and his sons, Ce and Quan. Their kingdom would be called Wu, based south of the Yangtze river.

The coalition against Dong eventually breaks apart and fails, and he is instead killed by his own general when members of his court hatch a plot to involve the two of them in a love triangle. With Dong gone, China once again descends into a violent power-struggle. The list of petty regional lords and pretenders to the throne is gradually whittled down until there remains a triumvirate of challengers—Liu Bei's Shu-Han, Ts'ao Ts'ao's Wei, and Wu under the Sun family. What follows is an epic, winding tale of political and military intrigue, plots, assassinations, battles of wit, moral dilemmas, and an ever-changing web of alliances and loyalties. Each kingdom has its moments of triumph and disaster, and their rulers all declare themselves to be the sole legitimate emperor.

***

There are perhaps four key moments that define the direction of the story following the founding of the Three Kingdoms. The first is the Battle of Red Cliffs (208 AD), fought on the Yangtze river between an alliance of Liu Bei and Sun Quan and the vastly more numerous invading forces of Ts'ao Ts'ao. Liu’s strategist, the legendary Zhuge Liang, prays for a favourable wind, enabling the allies to launch a daring fire attack and burn the Wei navy. This victory halts Ts'ao's momentum, but Shu and Wu eventually fall out over territorial disputes, and one of Sun Quan's generals later kills Liu Bei's beloved brother, Guan Yu.

Liu's rage at the death of his brother prompts him, against the advice of his followers, to invade Wu. The result, the Battle of Xiaoting (222 AD), is the second key turning point in the story. Wu's forces again deploy fire tactics to destroy the invading army, and the defeated Liu retreats to coalesce and focus his efforts against the more expansive kingdom of Wei.

From 228 to 234 AD, the unmatched Shu strategist Zhuge Liang leads a series of northern expeditions against Wei, and these campaigns comprise the third turning point. Although Zhuge uses his superhuman strategic abilities to achieve some remarkable results on the battlefield, none of his expeditions inflict a decisive blow, partly because Wei had by this time found its own talismanic strategist in Sima Yi. A long rivalry ensues between these two great minds, and while Zhuge is portrayed as having the edge, he is always foiled at the last moment by natural causes or by political failures in Shu following the death of Liu Bei. Zhuge's own demise then removes the greatest external threat to Wei's dominance.

Another key player to have passed away by this point is Ts'ao Ts'ao. Like the Han state before it, the kingdom of Wei was now in the hands of far less capable figures than its founder, leaving the way clear for the final key moment in the tale: Sima Yi's coup against Ts'ao Shuang and his seizure of power in Wei (249 AD). Sima's descendants go on to conquer Shu-Han (263 AD), declare their own dynasty (the Jin, 266-420 AD), and finally conquer Wu (280 AD).

And so it was that none of the Three Kingdoms survived to unify China. All of them ultimately became microcosms of the same dysfunction and decay that afflicted late Han, and they suffered the same end. This is the great irony of the Romance. However, it also helps to explain the enduring popularity of this tale, for it concerns not just the fortunes of states, but something much more intimate—the apparent powerlessness of human effort when stacked against the will of the Heavens and the crushing inevitability of fate. As the book's concluding poem states:

All down the ages rings the note of change, For fate so rules it; none escape its sway. The kingdoms three have vanished as a dream, The useless misery is ours to grieve.

8 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

The Anatomy of a Far-Right Idol: Karl XII of Sweden

On 30 November 2018, in the Kungsträdgården park in Stockholm, neo-Nazis from the Nordic Youth group marched towards the statue of a long-dead king. The stated objective of the group was to ‘re-civilize the West’ and to resist the ‘levelling of all cultures’—messages that have been shouted from beneath this statue, on this day of the year, for generations. Fighting promptly broke out between Nordic Youth supporters and counter-demonstrators, leading to two arrests.

The statue beside which this drama played out is of Karl XII, king of Sweden from 1697 until his death on 30 November 1718. He was the last to rule over the country during its ‘age of greatness,’ when Sweden briefly ranked among the most powerful nations in Europe. Although Karl does not feature very highly in the day-to-day consciousness of most modern Swedes, his military campaigns against Denmark, Poland and Russia still fascinate audiences through best-selling books and, more recently, video games. In 2012 he was even immortalised in four songs by the Swedish metal band Sabaton.

For well over a century, however, Karl’s legacy has also been closely associated with royalist, ultra-nationalist, and racist movements—including the Swedish Nazis in the 1930s. Throughout the twentieth century, 30 November was regularly marked by press reports of nationalist rallies, often leading to violence. A gathering in 2007 ended in similar fashion.

What drives this obsession? Why has Karl XII, out of all the militaristic kings in Swedish history, become a darling of the far-right? The answer lies largely in the fact that, as the leader of a besieged nation surrounded by larger opponents, his circumstances are broadly similar to an ultra-nationalist interpretation of modern Sweden. By dying in defiance against the fate of a doomed empire, Karl XII became a convenient martyr for nationalism.

***

The most common narrative strung by ultra-nationalist leaders is that of a struggle against seemingly insurmountable odds. The most obvious example is Adolf Hitler and his conspiracies about global Jewish dominance. Today, white nationalists across Europe emphasise a perceived attack from Islam and immigration, which, they argue, pose an existential threat to their cultures and traditions. For his modern admirers, the threats faced by Karl XII are largely analogous in scope.

When Sweden gained its independence from Denmark in 1523, it was a marginal and inconsequential nation with a population of perhaps 1 million. France, by comparison, was fast approaching 20 million, and Russia 10 million. Over the following two centuries, however, Sweden began to exert international power far beyond its demographic or economic stature, enabled by an advanced military establishment. At its height, the Swedish empire played a pivotal role in the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) and possessed a sprawling expanse of territory including modern Estonia and Latvia, parts of northern Germany, and small colonies in America.

The reasons for this expansion have been subject to debate. The most common answer is that Sweden feared encirclement by its larger neighbours—Denmark to the west, Poland to the south, Russia to the east—and felt compelled to fight for its survival. But there was also a racial and cultural aspect to this underdog mentality. As the denizens of an upstart nation, members of Sweden’s small educated class set about tracing a fanciful genealogy for their people which connected them directly with the sons of Noah. The message was that the Swedes, though marginal at the time, had a rightful place among the first rank of nations.

Whatever the reasons for its imperial expansion, Sweden’s power was already on a downward trajectory by the time Karl XII ascended to the throne in 1697. Denmark, Poland and Russia—all having suffered numerous defeats at Swedish hands—launched a joint attack on Sweden in 1700. The Great Northern War, as it is known, would prove to be the final act in Sweden’s imperial career.

Karl XII was just fifteen years old when he became king. As a boy, he had shown great intellectual promise under the attentive eyes of his tutors, but his principal interests turned out to be military. He would assiduously partake in mock battles and drills, and as king would insist on wearing military uniform, eating and living simply, and personally leading his armies. Like many European monarchs of this time, he cultivated the image of a warrior-king. Hagiographers would later list ‘precocious manliness’ and ‘manly gravity’ among his most striking features.

At the outbreak of the Great Northern War, Karl remarked: ‘I have resolved never to begin an unrighteous war; but I have also resolved never to finish a righteous war till I have utterly crushed my enemies.’ He duly began a remarkable spree of military victories: he besieged Copenhagen, defeated a much larger Russian army in Estonia, marched through Poland (installing a friendly king in the process), and invaded Saxony. His next campaign, however, was less well-fated. Marching through Russia in the biting winter of 1708-9, the Swedes were crushed at Poltava by a rejuvenated Russian army under Peter the Great.

After a period of exile in the Ottoman Empire, during which he tried and failed to provoke a sustained Russo-Ottoman war, Karl led an invasion of Danish-controlled Norway in 1714. He was ultimately killed during the siege of Fredriksten on 30 November 1718. The Treaty of Nystad in 1721 brought the Great Northern War, and with it the ‘age of greatness,’ to an end.

***

Karl XII’s campaigns brought the Swedish economy to the brink of disaster—the country was in severe debt, and its population began to shrink. But many commentators, far from criticising the social impact of his wars, have praised instead the spirit of national sacrifice and supposedly displayed by his compatriots. In 1895, for instance, the admiring historian Robert Nisbet Bain enthused:

Wonderful, indeed, was the dogged endurance and the persistent dutifulness of the bulk of the Swedish peasantry during the trials of Charles’s later years: to posterity it seems almost superhuman. Even the splendid valour of the Swedish soldier in the field was as nothing compared with the heroic endeavour of the Swedish yeoman at home to respond to the endless and ever increasing demands made upon him by the Government.

This dynamic lies at the core of Karl’s contemporary appeal: the Great Northern War can be packaged as a national struggle, and the king as the leader of a do-or-die collective effort of self-preservation. For a country which is now known internationally as a non-combative, welfare-oriented society with a liberal approach to migration, Karl XII represents an historical lodestone around which the far-right, who see these qualities as self-destructive, can build a very different, more assertive, and ultimately race-based identity.

Such associations are made possible, in part, by the inevitable blurring effect of three centuries, enabling the reduction of historical actors and events to vague notions such as national assertiveness. The real Karl was much more complex. He was indeed a militaristic man, but ‘nationalism’ in its current form would have been utterly incomprehensible to him, as it would be to anyone in the eighteenth century.

In any case, while there are many aspects of Karl’s life and character that are appealing to ultra-nationalists, there is one aspect above all which makes him a curious choice of hero: that he, like his idolaters, and like so many far-right heroes, found himself on the wrong side of history. Try though he did to preserve his endangered empire, his efforts were not only unsuccessful, but inflicted a period of extraordinary pain on the Swedish people. These two features—an indifference to suffering and a fatalistic commitment to a dying cause—are inextricably ingrained within far-right ideologies. It should come as no surprise that their historical heroes (or rather, the ahistorical versions of them created for far-right purposes) tend to be callous failures.

#politics#far right#sweden#history#nationalism#racism#charles xii#karl xii#swedishempire#stormaktstid#poltava#europe

0 notes

Photo

The Intermediate Sex

Examining a lost chapter in British queer history

Gender and sexuality are different things. At least, they are at the moment. The way we define our sexual selves does not, generally, dictate the way we define our gendered selves—or vice versa—and this is partly a result of the emphasis that early gay liberation campaigns put on the 'normality' of homosexuals in their day-to-day presentation (i.e. in line with their assigned gender). But before these campaigns gathered pace in the 1950s, there was a school of thought that believed homosexuality was, in fact, an intersex condition. In Britain it was largely gay men who pushed the concept of an 'intermediate sex,' hoping it would unlock public sympathy and ultimately help lift the ban on homosexual acts, in place since the sixteenth century. Despite its obscurity now, this chapter in British queer history has left behind a long and complex legacy which still affects the way we talk about gender and sexuality today.

The idea had its roots in nineteenth-century Germany, one of the epicentres of early sexology. Karl Heinrich Ulrichs suggested the idea of a 'third sex' called the Uranian, which, as Theo Lang put it in 1940, implied that homosexuals were actually females occupying 'male' bodies. One of the earliest expressions of of Uranian theory in Britain was to be found in Edward Carpenter's book The Intermediate Sex (1908), which observed that humans display a wide variety of 'gradations of Soul-material in relation to Sex'. Although Carpenter described the Urning (male Uranian) as having a 'defect,' he also argued that it gave them 'an extraordinary gift for … affairs of the heart'. By presenting Urnings in a sympathetic light, Carpenter tried to carve out a space in which the supposed femininity of the homosexual could become a virtue.

This mode of understanding survived well into the mid-twentieth century, with numerous gay writers picking up the baton. An anonymous author, under the pseudonym 'Anomaly,' argued in a 1927 book titled The Invert that:

[N]o one is exclusively male or exclusively female … [I]nverts are people in whom the combination of ingredients is such that [the] element which determines sex impulse is at variance with the sex structure … In other words, an invert's outward form is of the opposite sex to that of his sexual temperament.

Because Anomaly saw the psyche as, by definition, attracted to its bodily 'opposite,' he concluded that 'all psychosexual attraction is essentially heterosexual'. This implied two things: first, that homosexuals were not really men; and second, that the word 'homosexual' was in any case misleading. As such, the 'intermediate sex' theory posed a direct threat to the gender-binary and to the demonization of 'same-sex' love.

In 1954 the Conservative government in Westminster appointed the Committee on Homosexual Offences and Prostitution. It was tasked it with examining the law on homosexual intimacy between men, which at that time was still categorically illegal. As part of their evidence-gathering process the committee heard from Carl Winter, the homosexual curator of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, who told them that humanity 'is not divisible into two perfectly clear-cut sexes … on the contrary we all embody, for better or worse, many characteristics of both sexes … but not necessarily always in a body of the same sex as the psyche'. The implication was that homosexuals were merely a product of natural genetic variations, and as such it was unfair for the law to single them out. But in the maelstrom of competing ideas on sexuality in 1950s Britain, the 'intermediate sex' theory lost out.

The Committee's final report in 1957 did recommend the partial decriminalization of homosexual acts, but it made no mention of the concept of an intermediate sex. This was no doubt partly a reflection of the theory's intellectual ambition. It undermined the idea of two complementary sexes, introduced a concept similar to transsexualism, and discussed homosexuality using a lexicon totally removed from anything the political establishment or the general public was used to. Its thoughtful sympathy towards homosexuals chimed with the cautious tolerance of the liberal elite, but it was simply too alien, too threatening, and too confusing to be the basis for political change.

In the 1950s, anyway, a far less destabilizing argument for decriminalization was being codified. Peter Wildeblood, a former Daily Mail journalist imprisoned for 'gross indecency' in 1953, became one of the most prominent gay men of his time after publishing his memoir, Against the Law, in 1955. He spurned the notion of everyone possessing 'characteristics of both sexes' and famously condemned 'the pathetically flamboyant pansy with the flapping wrists'. Most homosexuals, he wrote, 'are not like that. We do our best to look like everyone else, and we usually succeed'. This is a telling passage, singling out the 'flamboyant pansy' only to convince the reader that he deserves no special attention. It insists that most homosexual men really are men—masculine, reserved, harmless. In a strictly binary-gendered society, this was a much more comforting proposition.

Wildeblood did not jettison the idea of mixed sex characteristics altogether. When invited to speak to the Committee, he told them of his encounters with homosexual prisoners 'who really are sort of women to all intents and purposes. They just happen to have a male body. They think like women and behave like women'. However, instead of invoking sympathy, he presents these people as pariahs who cause 'a lot of the public feeling against homosexuals'. This concern to avoid association with ostentatious behaviour fits into the wider blueprint of 'respectable' homosexual politics in the 1950s, later encapsulated by the campaigner Antony Grey's comment that one ought 'to dress, behave and speak in ways calculated to win the sympathetic attention of those whom you wish to influence'. In modern parlance we call this 'straight acting'. Whereas the 'intermediate sex' theory tried to legitimize new forms of gendered expression, respectability politics put the onus on homosexuals to scrupulously self-regulate their behaviours.

It was on the basis of this appeal to the normality of most homosexuals that the 1967 Sexual Offences Act was passed, decriminalizing homosexual acts between men in private. The 'intermediate sex' theory in its original guise fell by the wayside. But remnants of this remarkably imaginative and forward-thinking idea are still present in the way we discuss our identities today. For example, Uranian theory heavily influenced early conceptions of transsexual identity with its focus on 'male' and 'female' brains occupying 'the wrong body'. It also prefigured the notion of non-binary identities by recognizing that not everyone fits into cleanly-defined 'male' and 'female' boxes. Furthermore, by explicitly linking sexuality and gender within the same theoretical framework, it offered an early glimpse of the synergy between sexual and gender politics which is now evident in the acronym 'LGBT'. We are still, in a roundabout way, living with the legacy of a theory that was swept aside over fifty years ago.

#lgbt#gay#queer#history#britain#politics#sexuality#gender#trans#transgender#transsexual#intersex#homosexuality#wildeblood#wolfenden#conservatives#1950s#uranian#ulrichs

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Becoming a Quaker, and finding ‘God’

I was a full-time atheist for most of my teenage years. I say ‘full-time’ because I am currently something of a part-timer. I describe myself as a Quaker, or ‘a Christian of sorts,’ but I don’t always ‘believe’ in a God. This may sound odd, but to me it is a situation that gives me a peace I have never found before. My favourite song is a churning indictment of organized religion, and I am still deeply sceptical of all human entities which claim access to deeper truth. Other times I can be quite pious in my own way—that is, a stereotypically lax Quaker way.

My long-time distrust of religion boiled over into outright hatred in my teen years as I came to terms with being queer. The amount of pain that has been inflicted, and is still being inflicted, upon LGBT+ people in the name of religious belief is of an order that defies measurement. It didn’t help that every time queer issues were in the news as I grew up, religious representatives were almost always reiterating a tired and, as I later discovered, scripturally vacuous demonization of anyone who deviated from their artificial family-oriented idyll. It seemed that religion was only capable of being reactionary. I thought Bill Maher’s refrain made a lot of sense: ‘religion must die for mankind to live’.

This view was first entrenched, and then immediately exploded, by a formative school trip to two places of worship when I was studying for my A-Levels. The first was a Pentecostal church, in which the woman giving us a talk about her faith explained, unprompted, that the Armageddon was coming due to the ‘rise of gays’. I was surprised by the forwardness, but not by the sentiment, which seemed entirely consistent with what I had experienced of religion.

The second place of worship was a Quaker Meeting House, and here I had the closest thing to an epiphany I have ever experienced. The very first thing these Quakers told us about themselves is that they do not claim to have the answers: their faith is about asking the right questions. And, on the subject of same-sex love, we were given only positive messages and told about the Quakers’ long and impressive track-record on LGBT+ issues.

The style of worship also struck me. As an autistic person I regularly experience sensory overload. De-stimming is important, and finding peace sometimes feels impossible. Turmoil is my default state. But Quakers worship in near-silence, broken only by spoken ‘leadings’ which are (for many, at least) believed to be indications from God. The worshiper who feels they have something important to say will say it—the others will not respond but will try to take it in, and ponder it.

The peace I feel during meetings is an extraordinary sensation for me. Everything seems to slow down, the air becomes looser, my body stops reacting quite so severely to sensory stimulation. I have never spoken during a meeting—I prefer to sit and think, or sometimes just sit. If I have ever ‘experienced’ God, it is during these moments of hushed reflection.

Since beginning University in 2013 I have met many amazing Christians—people who reminded me what a good Christian looks like, and that religion need not be reactionary. When deployed well it can, and should, be a source of motivation for challenging social, political and economic boundaries. It can embody a permanently revolutionary love.

That is not to say I am now less sceptical about organized religion per se, but I have a more nuanced view. Speaking truth to power is always important, and so long as religious institutions are powerful it will be necessary to mock, berate, parody and criticize them. Nonetheless, the doubt haunts me that such an approach is incompatible with the religion I claim to practice. The thought that God hates me seeps through the cracks. I may never escape that worry, but I am at least learning to embrace my own contradictions.

42 notes

·

View notes

Photo

We should all be Luddites now

‘The Britain that is going to be forged in the white heat of this revolution will be no place for restrictive practices or for outdated methods on either side of industry.’

For a world that has grown accustomed to being reimagined by successive and ever-accelerating waves of technological change, Harold Wilson’s famed line from 1963 now seems rather innocuous. At least the first half does. The second half, referring to ‘restrictive practices’ on ‘either side of industry,’ is more likely to grate on the conscience of a twenty-first-century socialist, knowing as we do what came two decades later under Margaret Thatcher: the erosion of trade union rights, the ravaging of entire communities, mass-unemployment, and the obliteration of human dignity under the guise of ‘modernization’.

But a more telling and in some ways more significant passage from Wilson’s speech is usually forgotten:

Let us be frank about one thing. It is no good trying to comfort ourselves with the thought that automation need not happen here; that it is going to create so many problems that we should perhaps put our heads in the sand and let it pass by. Because there is no room for Luddites in the Socialist Party. If we try to abstract from the automotive age, the only result will be that Britain will become a stagnant backwater, pitied and held in contempt by the rest of the world.

No room for Luddites in the Socialist Party? This is the nub of Wilson’s argument: change is coming, and we either embrace it or are crushed by it. But this reference to the Luddites, a nineteenth-century protest movement which resisted mechanization in the textile industry, is misleading. In fact, if there is a lesson to be taken from the Luddites, it is precisely opposite to the one adopted by Wilson.

The thing about the Luddites is that they were right. They believed that the coming of textile-weaving machines threatened to enfeeble their craft, their livelihoods, their communities, their way of life, and that is precisely what happened. Organized labour had been formally outlawed by the Laws of Combination in 1799 and 1800, and the repressive attitude of the state closed off many potential channels of protest. So, from 1811-16, the Luddites began smashing textile machines and threatening the bosses who used them.

For our modern society, obsessed with ‘property,’ this is an unacceptable and dangerous precedent. That in itself reveals an awful lot about our warped priorities; property over personhood, commerce over community, economy over society. The only good is that which derives from The Market, and if that involves compressing human beings into cramped, squalid, dangerous, and soul-crushing existences, then so be it.

We are now experiencing a set of circumstances not dissimilar to those encountered by the Luddites. The ‘gig economy’ has become, for many, synonymous with long hours, low pay, insecurity, fear, and powerless servitude. Communities are again being broken apart. Ways of life are being brushed aside because The Market requires it. Meanwhile, the government takes a homeopathic approach to trade union rights. Eventually there will be no meaningful trace of medicine left.

Anyone who questions the regular human sacrifices that The Market solicits is liable to be branded a ‘Luddite’. Progress must march on, no-matter what that entails.

But there is nothing illegitimate or shameful about pausing to ask where we are headed. Technological change can, should, and often does lead to drastic advances in human wellbeing. But it is a question, as Wilson recognized, of how we utilize and manage it. There is no use in being a ‘wealthy’ society if that wealth is siphoned off to a small coterie of familiar recipients, whilst an underclass of abandoned, denigrated, and victimized citizens reel from the loss of one job after the next, and are shuttled from one rented accommodation to another.

We desperately need coping mechanisms. We need, in fact, the very centralized planning that Wilson advocated. Planning does not have to be overbearing, nor does it necessarily involve direct government involvement in every area of business and life. What it does involve is forward-thinking. We need to ask questions like: Whose livelihoods are put at risk by technological change? What skills do they need to thrive in this changing world? And how can we ensure that technology strengthens, rather than undermines, our sense of community?

More than anything, then, what we need is a National Education Service. A service that can be accessed at any time of life, to train and retrain, free at the point of use. If managed well, and given the resources it needs, it will transform Britain into the skills capital of the world. Communities, instead of being powerless as they are discombobulated, will be given the chance to define their own futures. That is the path that we can take if we are brave enough. The National Education Service is, after all, already Labour Party policy, and it is the single most transformative policy we have. We need to make more of a song and dance about it.

Meanwhile, we should recognize that Wilson was wrong: a socialist party needs its Luddites, just as much as it needs its Chartists, its Hardies, its Webbs, its Attlees, its Bevans and Bevins, and, yes, its Gaitskells. We need to think like Luddites, to put community and human wellbeing first, not The Market. We need to make a nuisance of ourselves, to always challenge those who reify economic change without sparing a thought for its consequences. It is not about putting ‘our heads in the sand,’ but about asking that most fundamental question: Do we serve The Market, or does it serve us?

In this century, it is not just manual and so-called ‘low-skilled’ livelihoods which are at risk. Every job at every level in every country will either be redefined or invalidated by the ‘white heat’ of our own revolution. We should all be Luddites now.

0 notes

Link

#Tim farron#libdems#homosexuality#lgbt#politics#general election#sin#religion#christianity#homophobia

0 notes

Text

Fire and Fury

If the 'lesson' we take from Trump is that someone with mental health difficulties can never hold a position of power, we will have learned the wrong thing.

It will take decades to undo that damage.

He isn't unsuitable because of this or that 'condition' diagnosed by people who have never spoken to him, he is unsuitable because he openly threatens to commit war crimes, because he is a white supremacist, because he knows precisely nothing and is unwilling to learn.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Mastering the Shadow of Gordon Brown

Why Labour must stop running from Brown's legacy

The memory of Gordon Brown's time as Chancellor and Prime Minister still hangs stubbornly over Labour's electoral prospects. Since the 2008 global financial crisis hit, the Conservatives have pushed the fallacious economic narrative that Labour's spending policies somehow caused the recession. Although the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn – with his history of rebellion against 'New Labour' – has in some sense mitigated the worst effects of this line of attack, the fact remains that any significant push for higher public expenditure is met with the complaint that Labour 'over-spent' between 1997 and 2010.

Under Ed Miliband’s leadership the party's response to the 'economic credibility' issue was muddled. His defence of the previous Labour Government's public investment sat uncomfortably with his commitment to slash some areas of spending. Corbyn, for his part, has challenged the issue more directly by promising greater spending in key areas and by directly attacking the 'political choice' of austerity. And the 2017 British social attitudes survey found that, for the first time in a decade, more people prefer higher spending and more taxation than oppose it. But the 'over-spending' charge remains a potent weapon in the Conservative armoury.

If Labour is to permanently master the shadow of Brown and put the austerity argument to bed, it must confront the Tory narrative at its historical core. That means taking a closer look at thirteen years that much of the left would rather forget; it also means taking charge of the political dialogue around spending and the financial crash. And in doing so, we might even find that there is far less to be ashamed of than current political dialogue would suggest.

***

The 'New Labour' brand was launched by Tony Blair and his allies in the mid-1990s as a response to four Tory victories in a row from 1979 to 1992. They believed the party had wasted eighteen years in the wilderness because it had been too left-wing, too ideological, and too addicted to spending. Gordon Brown played a key role in developing a centrist Labour manifesto and, as Shadow Chancellor, pledged that the party would match Conservative spending plans for its first two years in power. He did just that when Labour won by a landslide in the 1997 election. Government spending as a percentage of GDP reached record lows, at around 36%. 'Prudence' was Brown's watch-word.

The belt loosened when those two years were up. Spending on core public infrastructure increased significantly. The specifics of Labour's actions and achievements during this period is a separate matter, but to a large degree their spending increases were met with results; smaller class sizes and drastically reduced waiting times, for example. Nevertheless, many in the party remained wary of the charge of laxity with the public purse, and from this concern arose the principle imbalance of Britain's economic policies under Brown's stewardship.

Some of the increase in spending was funded by steady and consistent economic growth up to 2007; some of it, controversially, was paid for with the much-derided 'Private Finance Initiatives' which sought to fund public projects with private finance. But New Labour only increased taxation, the primary source of government revenue, by 2.3% of GDP. This precarious approach to revenue-raising prompted Polly Toynbee and David Walker to conclude that, far from over-spending, Labour under Blair and Brown under-taxed. It failed, in this view, to match the public's demand for greater investment with an argument for higher taxation. Thus 'tax and spend' simply became 'spend'.

Even so, public finances were not remotely in a state of crisis before the 2008 crash. Brown endeavoured to keep national debt below 40% of GDP – a somewhat random target, but one that he achieved. With a national debt of 36.5% of GDP in 2007-8, Britain's was the second lowest of any major economy (and at historically low interest rates). The budget deficit was just 0.6% of GDP by 2007. It is therefore ludicrous to single out Blair and Brown for 'over-spending' in normal circumstances.

The real failure of Labour's economic management was its refusal to challenge the new orthodoxy of low spending coupled with low direct taxation established by Thatcher. In 1979 the top rate of income tax stood at 83% and the basic rate at 33%. By 1997 the top rate was 40% and the basic rate was 23%. At the same time, the majority of the state's profitable or near-profitable industries were privatized – sold off – creating a government revenue black hole that was only partially filled by the arrival of North Sea oil. Harold Macmillan, who served as Conservative Prime Minister from 1957 to 1963, likened this privatization spree to 'selling the family silver'.

To this can be added the end of 'full employment,' the ideal adopted since 1945 which, for the most part, kept unemployment in the hundreds of thousands rather than the millions. But stringent cuts in government expenditure and the shrinking of the public sector caused unemployment to skyrocket, averaging 11.7% in 1982-5 and 9.3% in 1986-9 – along with the associated welfare bill. It remained below 6% for most of 1997-2007 but unemployment figures in the millions had been normalized, and Brown accepted it. The structural disparity that Thatcherism built into the British economy remains to this day.

For both Brown and Britain, however, the greatest hazard left by Thatcherism lay in the promotion of the financial services sector at the expense of manufacturing. To be sure, the inexorable growth of finance yielded great benefits as well as risks – by the 2000s there was no doubting that London was the financial capital of Europe. But the risks were existential, and from these sprang the global disaster of 2008. The threat of financial meltdown, necessitating emergency spending of extraordinary proportions, is the real source of our present indebtedness.

***

For the majority of Gordon Brown's time in No. 10, the single greatest issue facing Britain and the world was the global financial crisis. This was the deepest downturn in the financial markets since the Wall Street Crash in 1929. This, like the hollowing out of old government revenue streams, is a complication dating back to the 1980s.

Nigel Lawson, Margaret Thatcher's second Chancellor of the Exchequer, oversaw the deregulation of the finance sector in the late-1980s. The centrepiece of his reforms was the Financial Services Act 1986, setting up the system of 'self-regulation' that, in practice, often meant no regulation at all. The City of London was encouraged to mimic and ultimately rival New York in share trading. While the government came to rely ever more on the City to provide revenue, it allowed Britain's manufacturing base to decline at a faster rate than in any other comparable economy – a trend that continued under New Labour.

In the coming years there were multiple warning signs laying bare the fragility of this new economic balance; on 'Black Monday' in 1987, when shares in London lost 25% of their value; and 'Black Wednesday' in 1992, when currency speculators initiated a run on sterling and cost the government over £3 billion. But the most significant portent of future troubles was the 1997 Asian Crisis, when the effects of a currency crash in Thailand spread with alarming speed and ease to the over-heating economies of south-east Asia.

Brown recognized that the risk of contagion in a globalized financial world was enormous. In a speech in New York he argued for greater spending powers for the IMF and World Bank, as well as closer cooperation in regulating world finance so that developing crises could be contained. On this Brown must receive some credit; for thirteen years from 1997 to 2010 he doggedly made the case for a global solution to a global problem. But the belief in minimal regulation held by most world leaders proved all but immovable.

At home, however, Brown's record cannot be defended so easily. As Chancellor, ensuring that the financial sector was properly regulated was ultimately his responsibility. He declared that the City of London required 'a world-class supervisory framework'. That he failed to produce such a framework is practically beyond doubt.

As well as granting independence to the Bank of England, Brown created the Financial Services Authority (FSA) to form, together with the Treasury, a tripartite regulatory system. This was supposed to be capable of picking up early tremors and alert the government that something was awry. But in practice this apparatus was a paper tiger. A lack of regulatory zeal and coordination between the three bodies left the government none the wiser to the extent of the problem; one that had been brewing beneath the shiny veneer of Britain's banks since 1986.

This problem erupted with daunting violence after Brown ascended to the top office in 2007. The principal issue was the implosion of America's sub-prime mortgage system (in which lenders had agreed to give customers mortgage packages regardless of their actual ability to keep up their payments). Banks across the world had bought into this market with incredible recklessness, meaning almost every major economy was contaminated. Britain's banks, free from proper oversight, were no exception.

The case of Northern Rock became a microcosm of the wider issue when it hit trouble in 2007. It had extended into the property sector beyond what could be safely supported by its flow of capital. When lending between banks seized up following events in America, the Rock turned to the Bank of England for immediate support. Customers, having lost confidence, initiated the first run on a British bank since 1866. It could no longer survive on its own.

Here, as with taxation, Brown's fear of appearing too left-wing prejudiced his response. He was determined to find a private buyer for the Rock but no serious offers were forthcoming. It was only after months of dithering that he decided upon taking the bank into government ownership.

From this point on, however, his actions became more decisive. Recognizing the nature and gravity of the situation when many of his peers did not (with the notable exception of Vince Cable), Brown became a vital cog in the global response to the crash – which soon turned to recession.

***

The notion of a bank being 'too big to fail' now conjures up universally negative feelings, particularly on the left. To be sure, the banking sector should never have been allowed to develop into the lumbering, unsupervised behemoth that it had become by 2007. But when faced with the immediate prospect of total financial meltdown, the idea of bailing out a bank rather than letting it fail has some paradoxically progressive credentials.

At the time of the crash, the dominant theory regarding bank failures was that bailing them out would pose a 'moral hazard' – that is, it would allow banks to think that there are no consequences for excessive risk-taking. But most leaders had only accounted for a single large bank failing, not for an epidemic of failures. The shockwave from one major bank after another ceasing operations would have had cataclysmic social and economic repercussions. Some integral banks (such as RBS, with an international business larger than Britain’s entire economy) were therefore, in every sense of the term, too big to fail. Recession could readily have turned to depression.

The Brown government, to its credit, took an holistic approach to bailing out the banks. First, the Treasury would buy up toxic assets and replace them with government bills, providing emergency relief for the most infected institutions and thereby restoring liquidity (the availability of lending). Governments around the world were taking similar steps, but the novelty of Brown's response lay in his insistence upon coupling liquidity with recapitalization. In essence, the government would pump hundreds of billions of pounds into the financial sector to ensure banks had the capital to function.

Soon enough every major government was taking similar steps. The pivotal moment came in April 2009 at the conclusion of the G20 conference in London. Brown and Nicolas Sarkozy, the French President, had convinced other heads of government to attend what was usually a conference of finance ministers – a formidable achievement in itself. The headline result of the meeting was a combined $1 trillion international rescue package, the largest ever agreed. But arguably more important was the commitment to unprecedented cooperation between central banks and the creation of a World Stability Board to provide an early-warning-system in future.

It was during this period of hurried financial fire-fighting that the UK's national debt and budget deficit shot upwards. National debt nearly hit 85% of GDP, while the budget deficit increased more than tenfold, to 6.9% in 2010. The social effects were considerable as well, with unemployment peaking at 8.5% in 2011. But, had the government not rescued the banking sector and continued to stimulate the economy in the immediate aftermath, things could have been infinitely worse.

Put simply, Brown did not cause the crash and nor did government spending. The crash was caused by a light-touch (or no-touch) approach to regulation and the failure of successive leaders to challenge that attitude, Blair and Brown included.

In fact, the actions Brown took to contain the crisis helped to prevent a full-on economic depression. At that moment in time, not bailing out the financial system would have been vastly more damaging to the country. The question now is whether we obsess over the fallacious theory of austerity or redirect our efforts towards enacting concrete measures to tame the banking sector. Only by taking the latter route can a repeat of 2008 be prevented.

***

So why is it important for Labour to make this argument? Why must it return to this uncomfortable time in its history?

The primary reason is that in politics narrative is everything. Labour has handed the Conservatives a monopoly on narrative-building, causing the entire political debate to revolve around a sadistic, factually vacuous portrayal of recent history. Corbyn’s party is presently benefiting from a turnaround in public opinion regarding public investment, but the pendulum will inevitably swing back and the Conservatives will push their aging arguments with renewed vigour.

Labour must permanently change the terms of debate. And to do that, it must confront its fear of Gordon Brown. It should embrace Brown's successes while initiating a public debate about his real failures, particularly banking regulation. Far more emphasis should be placed on the Conservatives’ record as the party of deregulation, because the mess the government complains of inheriting is largely their own fault.

Labour’s long-term prospects therefore depend heavily on the party’s willingness to take ownership of Gordon Brown; to diffuse the tired old Conservative tale about over-spending and to blunt the axe of austerity. It will take patience and courage, but the pay-off could be incalculable.

#labour#ge2017#gordonbrown#austerity#conservatives#economics#government#jeremycorbyn#corbyn#2008#finance#banking#edmiliband#miliband#newlabour#brown#blair#thatcher#1980s#debt#nationaldebt#deficit#budget deficit#history#britain#uk politics#uk#politics

0 notes

Text

The Road to 1967

Lessons from the Sexual Offences Act

27 July 2017 marks the fiftieth anniversary of royal assent being given to the Sexual Offences Act 1967, which decriminalized acts of intimacy between men in England and Wales so long as they were conducted in private (similar acts between women had never been against the law).

The Act has rightly been seen as a watershed moment in British social history. It is often portrayed as the first major step on the long road towards gay, and then LGBT+, equality. But, whilst it is worthy of celebration as a critical legislative achievement, the nature of the debate which preceded and surrounded it contained some worrying portents for the future course of queer politics.

Crucially, it demonstrated the ease with which any community and any rights campaign can devolve into assimilationism. The language of 'respectability' was pervasive, with homosexuals being divided into distinct categories; the harmless 'inverts' on the one hand, and the dangerous 'perverts' on the other. This paradigm was deployed extensively by the 1967 Act's champion, Leo Abse, and dates back to 1952 and before. It is common for the Act to be listed among the achievements of the 'Swinging Sixties,' but it was just as much a product of the fifties.

Homosexuality's complicated legal history in Britain provided the backdrop to debates in the 1950s. The prosecution of homosexuality had its roots in the 1533 Buggery Act, which stipulated death as the penalty. This remained the primary basis for the conviction of homosexuals until 1861, when the Offences Against the Person Act replaced the death penalty with a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. The famous Labouchère Amendment to the 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Act followed, criminalizing 'gross indecency' and therefore encompassing all acts of intimacy between men, not just 'buggery'.

The most high-profile of Labouchère's victims was Oscar Wilde, who was sentenced to the maximum two years' hard labour in 1895. Later, the 1898 Vagrancy Act imposed stricter regulations with regards to importuning men for 'immoral purposes,' and the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1912 set the maximum penalty for importuning at six months' imprisonment.

Underlying all this legislation was a sense of embarrassment; an attempt to keep the subject of homosexuality away from the public sphere. Naturally, for this reason, it was seldom discussed by politicians or other leading figures.

***

Things began to change in 1952. On the one hand, Michael Schofield (under the alias 'Gordon Westwood') published his sympathetic book Society and the Homosexual, in which he argued that the silence must be broken because most people, in their ignorance, were 'guided by untutored superstitions rather than the facts'. The time had come, he believed, for the 'harsh and vindictive' approach to homosexuals to change.

In the same year, by contrast, the Sunday Pictorial published a series of articles by Douglas Warth titled 'Evil Men'. Warth wished to lift the 'scornful silence' on homosexuality for a very different reason. He thought it was 'providing cover for an unnatural sex vice which is getting a dangerous grip on this country'. Despite his more hostile attitude toward homosexuals, however, Warth agreed with Schofield that prison was not the answer. His solution was to open medical facilities where men could be ‘treated’ until they 'threaten society no more'.

The concept of medically treating homosexuals became a major theme in both pro- and anti-decriminalization rhetoric in years to come. Robert Boothby, the backbench Conservative MP who became the primary champion of decriminalization in the 1950s, argued in a 1953 memorandum to the Home Secretary, Douglas Maxwell Fyfe, that 'it is the duty of the State to protect youth from seduction; and society from acts of public indecency; but not to punish psychological disorders – rather to try and cure them.'

Boothby, in his attempts to convince Fyfe to set up an inquiry into the law on homosexuality, was among the most prominent purveyors of the respectability paradigm. He judged that, if he was to succeed in changing the law for the respectable 'gifted citizens' who were unjustly targeted for being homosexuals, he would have to distance those people from their more scandalous counterparts. Thus, he sought to reassure people of his own disgust towards the 'homosexual underground' which posed 'a continuous menace to youth'. More overtly, he argued that the punitive law did not 'achieve the objective of all of us, which is to limit the incidence of homosexuality and to mitigate its evil effects'.

Respectability was also deployed by Peter Wildeblood, the homosexual Daily Mail journalist who was among the three establishment figures brought to court for committing 'gross indecency' in the 1954 Montagu trial. After serving his 18-month prison sentence, Wildeblood launched a scathing attack on 'the pathetically flamboyant pansy with the flapping wrists, the common butt of music-hall jokes and public-house stories. Most of us are not like that. We do our best to look like everyone else, and we usually succeed.'

Wildeblood's invective became particularly significant when he was interviewed by the Wolfenden Committee, established by Maxwell Fyfe to look into potential legal reforms on both prostitution and homosexuality. Most of the arguments heard by the Committee in favour of decriminalization utilized varying versions of the inversion/perversion paradigm. The result was that those men who were most frequently targeted by the police during the 'witch hunt' of the 1950s – the 'flamboyant' homosexuals often arrested in public places such as lavatories – were perceived as dead-weight by the likes of Wildeblood. He believed that the key to changing public opinion on the matter was to disassociate upstanding men like himself from the 'pansies'.

The 1957 Wolfenden Report did recommend that homosexual acts in private should be decriminalized.The common thread throughout the Report was a belief that what is done in public and is perceived to damage society is within the remit of the government to regulate. What is done in private, to no wider detriment, is not.

But while many of the Report's recommendations on prostitution were put into action by the then Home Secretary, R. A. Butler, most of those on homosexuality were left untouched. Partly this was because many of those in favour of decriminalization agreed that a large number of homosexuals were indeed socially harmful and even malicious, thereby reinforcing established prejudices. As a result, they failed to properly challenge the logic underlying the status quo. The tendency on both sides of the argument to conflate the 'perverted' homosexual with the paedophile enhanced this problem.

Equally, Butler's refusal to enact decriminalization was due to his own belief, supported by the Committee, that homosexuality should be subject to further sociological and criminological research – two disciplines that were in vogue in the 1950s.

Meanwhile, the issue of public opinion in the aftermath of the Report added another layer of complication. An unscientific poll of Daily Mirror readers found 51% against decriminalization and 47% for it, while a Gallup poll showed 47% against and 38% for. Cabinet discussions on the Report concluded that there was 'not a sufficient measure of public support for the Committee's recommendations' for the government to act on them.

It is arguable as to whether decriminalization would have stood a better chance under the Conservatives had those in favour adopted a more universal approach to changing public opinion towards all homosexuals, not just those of high social standing. Certainly, Butler and many of his colleagues were not ideologically opposed to decriminalization – rather, they worried about the potential backlash and took the path of least resistance.

***

Either way, in the 1960s the push for decriminalization gradually gained momentum. The Homosexual Law Reform Society, for instance, had been founded in 1958. Although this was initially dismissed as 'a spasmodic campaign' by Butler, its publications kept the issue in the public mind. This was accompanied by a steadily growing list of leading figures and bodies (including the Church of England's Moral Welfare Council) favouring decriminalization.

In 1960 the House of Commons finally got a chance to vote on the Wolfenden Report's recommendations on homosexuality. No new arguments were raised, and the House voted against the motion by 99 'ayes' to 213 'noes'. Perhaps the most significant 'aye' vote from an historical perspective is that of Margaret Thatcher, although she did not vote when the Commons finally passed decriminalization in 1966.

In 1964 the struggling Conservative government was replaced with a Labour administration under Harold Wilson. The new Home Secretary, Roy Jenkins, took a much more lenient approach to issues like the death penalty and homosexuality, and was instrumental in creating what was later derided by social conservatives as the 'permissive society'. Instead of bringing its own bill to Parliament, the government cleared the way for a back-bench MP to do it.

Leo Abse's Sexual Offences Bill passed through the Commons in 1966 and became law in 1967, thus decriminalizing private homosexual acts between consenting men aged over 21. It is significant, however, that the distinction between respectable and non-respectable homosexuals remained firmly entrenched. The Act contained a clause specifically singling out acts committed in public lavatories as an example of what would not count as 'private'. The spectre of the 'witch hunt' loomed large.

And Abse, himself a somewhat flamboyant individual, warned that homosexuals should 'show their thanks' for the Act by refraining from 'ostentatious behaviour'. The law had changed, but there was a great deal of work still to be done to remove the stigma hanging over most queer people – a stigma that violently resurfaced during the 1980s and which the likes of Boothby and Abse had done much to reinforce.

***

In the decades following 1967, therefore, much of the time and effort of gay rights campaigners was consumed by the need to overturn some of the orthodoxies established by the Sexual Offences Act. This included the age of consent, which only reached parity with the heterosexual age in 2000. Equally, the idea that queer people should be respected on their own terms, regardless of how they dress and act, is a fairly recent innovation that gathered pace from the 1970s onwards.

So, in 2017, the Sexual Offences Act of 1967 should be viewed with a healthy mixture of celebration and introspection. It contains some important lessons that the modern LGBT+ movement should not ignore.

Most importantly, it shows the limitations of the divide-and-assimilate approach favoured by Peter Wildeblood in the 1950s. Whilst it is tempting for those of us who do not attract a great deal of public scorn to push our less accepted counterparts away for our own benefit, we must remember that this is inherently short-termist. It stores up and reinforces problems that we will only have to confront in the future. And it gives those who peddle hatred a degree of affirmation.

This is a relevant lesson for rights campaigns of all varieties. In the modern context we can recognize similarities in the way that some LGB+ people would prefer to ‘drop the T,’ or the reluctance in some quarters to recognize non-binary gender identities. Another example was seen in the debates preceding the passage of Same-Sex Marriage in the UK, when opponents repeatedly pushed the charge that bestiality or having multiple partners would be next. Too many equality campaigners failed to challenge the notion that polyamorous relationships are socially undesirable; and worse, that they deserve to be mentioned in the same sentence as bestiality.

So although we have come a long way from the language of 1967, the threat of a relapse is ever-present.

We must therefore endeavour to be all-encompassing and to challenge our own prejudices just as much as we challenge other peoples'. This does not mean that we should be insensitive to nuance, or that rights movements should try to act as a single conglomeration. Rather, it means rejecting the strategy of abandoning and demonizing those pushed to the fringes of society for our own benefit. Now, on the fiftieth anniversary of the Sexual Offences Act, seems the perfect time to make that case.

#sexualoffencesact#sexualoffencesact1967#1967#lgbt#lgbtrights#gayhistory#gay history#gay#sexual offences act#1960s#sixties#fifties#swinging sixties#1950s#labour#conservatives#uk#united kingdom#britain#great britain#trans#transgender#social history#pride#queer#lesbian#swingingsixties#history#politics#pride month

0 notes

Text

As someone with autism, Theresa May’s treatment worries me

One of the media's dominant themes during the 2017 General Election campaign was Theresa May's lack of charisma. The prime minister was near-universally lambasted for being too formulaic and for seeming unnatural in front of cameras. While Jeremy Corbyn appeared to be more free-flowing, more of an open book, more capable of improvisation and forming personal connections, 'Maybot' has become the standard nickname for the Conservative leader.

I was torn down the middle during the campaign. As a Labour members I have no sympathy for Theresa May's policies – not least her hollowing-out of the disability benefit system, her disregard for rising poverty, and her sadistic commitment to austerity. There was even a sense of comeuppance after the similar treatment dished out against Labour's Gordon Brown.

But as someone on the autism spectrum, I couldn't help but feel uneasy with the way she was attacked on a personal level for supposedly lacking humanity. It reminded me too much of my own experience.

Like many autistic people, I am used to comments about my unusual demeanour. My voice is either too fast or too slow, too loud or too quiet. My hand gestures are erratic and difficult to read. I don't understand most jokes, I seize up when talking to someone new, and I easily become overloaded. My defence mechanism is to fall back on pre-cooked answers, with something stored for most situations. I am formulaic by nature.

Although Theresa May is not, to my knowledge, on the autism spectrum, this is largely beside the point. After all, it isn't just autistic people who struggle with social communication. And while one could argue – or hope at least – that the media and public would be less inclined to attack an openly autistic politician for their traits, I think that is wishful thinking.

Even if the more high-minded media adjust their behaviour, try to imagine the tabloids doing the same. This scenario also presupposes that the politician in question reveals their autism publicly. No-one, even a senior political figure, should feel that divulging personal information is a prerequisite of being treated with respect.

At the end of the day, this isn't about Theresa May at all. The types of attack hurled at her and Brown normalize a certain way of thinking that treats anyone who is socially different – and, by extension, those with social disabilities – with suspicion. It sends out a message that it is acceptable to mock someone for being 'robotic,' without thinking about the many legitimate reasons for being that way. This is the real problem.

Ideally the media and political parties will exercise a little more discretion in future. Attack May (or whoever replaces her) for her record; for the things she has overseen. Attack the content of her messages rather than her skill in delivering them. And resist the sometimes overwhelming urge to join the tabloids in the gutter.

#autism#theresa may#conservatives#ge2017#general election#corbyn#disability#maybot#labour#media#charisma#politics#british politics

0 notes

Text

Legal Timeline of Homosexuality in England and Wales

Looking at the legal history of homosexuality on the fiftieth anniversary of partial decrminalization in 1967

* Scotland and Northern Ireland operate their own legal frameworks and so the timeline in these nations differs greatly from that of England and Wales.

1533

The criminalization of male homosexuality in the UK begins with the 1533 Buggery Act. This made the 'abominable vice of buggery' a specific criminal offence for the first time. The maximum penalty was death. This remained the primary basis for prosecuting homosexuals for centuries.

1828

Robert Peel, the Home Secretary, removes the death penalty from homosexuality and many other crimes.

1861

The Offences Against the Person Act expands the scope of the law and introduces a new maximum sentence of life imprisonment for causing 'grievous bodily harm' (as buggery was thought to do).

1885

Henry Labouchere introduces his 'Labouchere Amendment' to the 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Bill. This proposed to make 'gross indecency' a criminal offence, therefore criminalizing any act of intimacy between men that was thought to be inappropriate.

It was passed through Parliament with almost no debate. The most famous victim of this law was Oscar Wilde, sentenced to two years' hard labour in 1895.

1921

The Conservative MP Frederick Macquisten proposes to expand the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885 to criminalize 'gross indecency between female persons' as well. He claimed that the 'falling away of feminine morality was to a large extend the cause of the destruction of the early Grecian civilisation, and still more the cause of the downfall of the Roman Empire.'

Macquisten's proposal was accepted by the House of Commons but rejected by the House of Lords. The debate in the Lords laid some of the groundwork for the eventual decriminalization of male homosexuality. Lord Malmesbury said that 'the more you advertise vice by prohibiting it the more you will increase it.' The same argument is soon being made about male homosexuality.

1936

The word 'homosexuality' first appears in Hansard, the record of everything said in Parliament. Gradually replaces terms like 'buggery,' 'sodomy,' and 'gross indecency'.

1948

The Criminal Justice Act of 1948 opens the way for magistrates to sentence homosexuals to probation with 'treatment' by a medical professional. The practice of what is now known as 'conversion therapy' begins to take hold.

1954