#Classical Economics

Note

Why do economists need to shut up about mercantilism, as you alluded to in your post about Louis XIV's chief ministers?

In part due to their supposed intellectual descent from Adam Smith and the other classical economists, contemporary economists are pretty uniformly hostile to mercantilism, seeing it as a wrong-headed political economy that held back human progress until it was replaced by that best of all ideas: capitalism.

As a student of economic history and the history of political economy, I find that economists generally have a pretty poor understanding of what mercantilists actually believed and what economic policies they actually supported. In reality, a lot of the things that economists see as key advances in the creation of capitalism - the invention of the joint-stock company, the creation of financial markets, etc. - were all accomplishments of mercantiism.

Rather than the crude stereotype of mercantilists as a bunch of monetary weirdos who thought the secret to prosperity was the hoarding of precious metals, mercantilists were actually lazer-focused on economic development. The whole business about trying to achieve a positive balance of trade and financial liquidity and restraining wages was all a means to an end of economic development. Trade surpluses could be invested in manufacturing and shipping, gold reserves played an important role in deepening capital pools and thus increasing levels of investment at lower interest rates that could support larger-scale and more capital intensive enterprises, and so forth.

Indeed, the arch-sin of mercantilism in the eyes of classical and contemporary economists, their interference in free trade through tariffs, monopolies, and other interventions, was all directed at the overriding economic goal of climbing the value-added ladder.

Thus, England (and later Britain) put a tariff on foreign textiles and an export tax on raw wool and forbade the emigration of skilled workers (while supporting the immigration of skilled workers to England) and other mercantilist policies to move up from being exporters of raw wool (which meant that most of the profits from the higher value-added part of the industry went to Burgundy) to being exporters of cheap wool cloth to being exporters of more advanced textiles. Hell, even Adam Smith saw the logic of the Navigation Acts!

And this is what brings me to the most devastating critique of the standard economist narrative about mercantilism: the majority of the countries that successfully industrialized did so using mercantilist principles rather than laissez-faire principles:

When England became the first industrial economy, it did so under strict protectionist policies and only converted to free trade once it had gained enough of a technological and economic advantage over its competitors that it didn't need protectionism any more.

When the United States industrialized in the 19th century and transformed itself into the largest economy in the world, it did so from behind high tariff walls.

When Germany made itself the leading industrial power on the Continent, it did so by rejecting English free trade economics and having the state invest heavily in coal, steel, and railroads. Free trade was only for within the Zollverein, not with the outside world.

And as Dani Rodrik, Ha-Joon Chang, and others have pointed out, you see the same thing with Japan, South Korea, China...everywhere you look, you see protectionism as the means of achieving economic development, and then free trade only working for already-developed economies.

#political economy#mercantilism#economic development#early modern state-building#early modern period#laissez-faire#classical liberalism#classical economics#economics#economic history

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Theories of the Philosophy of Macroeconomics

The philosophy of macroeconomics deals with the study of large-scale economic phenomena, such as aggregate output, employment, inflation, and economic growth. It seeks to understand the principles, assumptions, and implications of overall economic activity and the interactions between different sectors of the economy. Some key theories in the philosophy of macroeconomics include:

Classical Economics: Classical economics emphasizes the long-run equilibrium of the economy, where prices and wages adjust to ensure full employment and resource utilization. It stresses the importance of free markets, minimal government intervention, and the self-regulating nature of the economy.

Keynesian Economics: Keynesian economics, developed by John Maynard Keynes, focuses on short-run fluctuations in economic activity and the role of aggregate demand in determining output and employment. It advocates for government intervention through fiscal policy (such as government spending and taxation) and monetary policy (such as interest rate adjustments) to stabilize the economy and address unemployment during recessions.

Monetarism: Monetarism, associated with economists like Milton Friedman, emphasizes the role of monetary policy in influencing aggregate demand and economic outcomes. It argues that changes in the money supply directly impact inflation and economic growth, advocating for stable and predictable growth in the money supply to maintain price stability and promote long-term economic growth.

New Classical Economics: New classical economics incorporates microeconomic foundations into macroeconomic models and emphasizes the rational expectations hypothesis. It posits that individuals form expectations about future economic variables based on all available information, leading to self-correcting market outcomes and limited effectiveness of government policies.

New Keynesian Economics: New Keynesian economics builds on Keynesian principles but incorporates microeconomic foundations and imperfect competition into macroeconomic models. It emphasizes the role of nominal rigidities, such as sticky prices and wages, in explaining short-run fluctuations in economic activity and advocates for countercyclical policies to stabilize the economy.

Real Business Cycle Theory: Real business cycle theory attributes fluctuations in economic activity to exogenous shocks to productivity and technology. It argues that changes in real factors, such as productivity shocks, drive business cycles, while monetary and fiscal policy have limited effects on real economic outcomes.

Post-Keynesian Economics: Post-Keynesian economics extends Keynesian principles by emphasizing the role of uncertainty, financial instability, and institutional factors in shaping economic behavior. It critiques mainstream macroeconomic models for their simplifying assumptions and advocates for a more heterodox approach to macroeconomic analysis.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT): Modern Monetary Theory challenges traditional views on fiscal policy and government finance, arguing that countries with sovereign currencies can issue fiat money to finance government spending without facing solvency constraints. It emphasizes the role of fiscal policy in achieving full employment and price stability, advocating for policies that prioritize job creation and public investment.

These theories and approaches in the philosophy of macroeconomics provide frameworks for understanding the determinants of aggregate economic activity, the role of government policy, and the dynamics of economic fluctuations and growth.

#philosophy#epistemology#knowledge#learning#chatgpt#education#ethics#psychology#economics#economic theory#theory#Classical economics#Keynesian economics#Monetarism#New classical economics#New Keynesian economics#Real business cycle theory#Post-Keynesian economics#Modern monetary theory (MMT)#macroeconomics

1 note

·

View note

Text

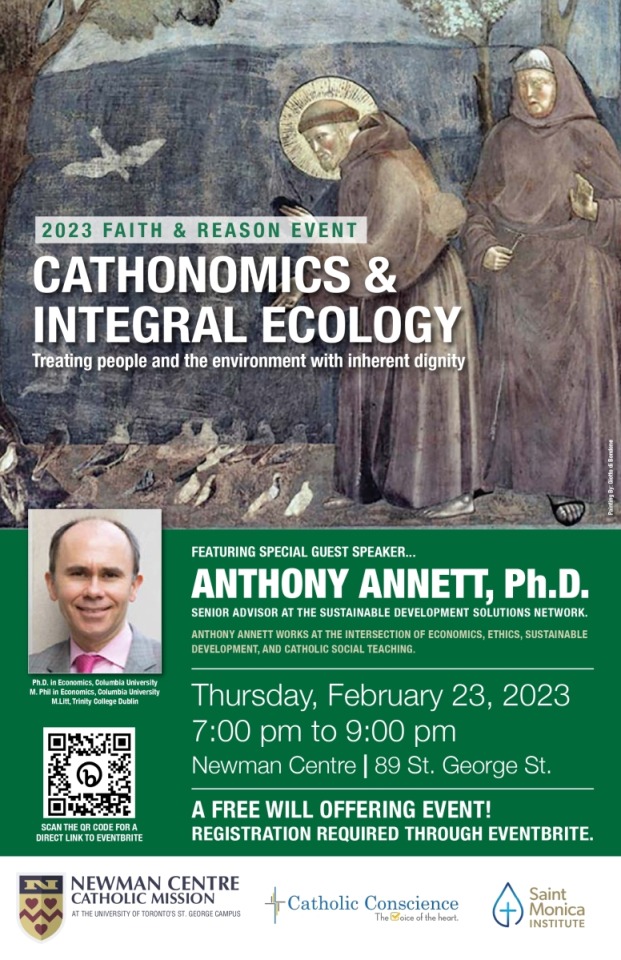

Cathonomics & Integral Ecology - Treating People and the Environment with Inherent Dignity

Timestamps: 00:00:00 Introductions Part 1 – the 10 Principles of Catholic Social Teaching 00:04:55 – 1. the Common Good 00:06:55 – 2. Integral Human Development 00:07:55 – 3. Integral Ecology 00:09:05 – 4. Solidarity 00:10:07 – 5. Subsidiarity 00:11:47 – 6. Reciprocity & Gratuitousness 00:13:25 – 7. the Universal Destination of Goods 00:14:34 – 8. the Preferential Option for the Poor 00:15:37 –…

View On WordPress

#Anthony Annett#Capitalism#Catholic Conscience#Catholic Social Teaching#Catholic Third Way#Catholicism#Cathonomics#Christine Lagarde#Classical Economics#Climate#Climate change#Columbia University#Conservative#Economics#Environment#Environmental science#Environmentalism#European Central Bank#European Union#Fordham University#Free Market#Georgetown University#Homo-economicus#Ideology#Integral Ecology#Integral Human Ecology#International Development#International Monetary Fund#Jeffrey Sachs#Justice

0 notes

Text

might have to start learning latin on my own. ermmm salwe qwuirites....

#having a mini breakdow#n#nope its all good its not like i wanted to study something that was my PASSION anyway#east asia buck the fuck UP!!! WHERE ARE MY CLASSICS PROGRAMMES!!!!!#when i found out uk taught latin gcses i literally fell to the ground like wow life is so unfair :'DDDDDD. me? i got. economics.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s interesting to see how G-Witch flips the traditional Gundam dynamic of space vs. earth, with people from earth being the economically exploited underclass while space is (seen as) the domain of the ultra-wealthy. I wouldn’t be surprised if this is in response to increasing discussions of space colonization specifically among the wealthy, particularly men like Musk.

#alex.txt#g witch#gundam the witch from mercury#classic u.c. space vs. earth is a diaspora of economic refugees#while space vs. earth in g witch is the wealthy fleeing the polluted world they brought about (while continuing to squeeze profit from it)#it also feels a tad asimov but that might just be my asimov obsession speaking

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maybe this is a hot take, or maybe this is a super cold take, but

Home ec & Cooking classes are infinitely more valuable than any of the so called "core" high school classes.

#education#home ec#home economics#cooking#education systems and institutions#solarpunk#solunarpunk#yes some of the core classes are also basic skills#like critically analyzing texts#or basic algebra that can be applied to daily living situations#a general understanding of the earth and space and how our reality works is definitely important#but thats middle school stuff#understanding moles and reading 1000 classic novels is fundementally less important than being able to cook an egg

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Julian Adorney and Mark Johnson

Published: Jun 10, 2024

There’s a sense that the liberal order is eroding.

What do we mean by that? By “liberal order” we mean three things: political liberalism, economic liberalism, and epistemic liberalism.

Politically, it’s tough to shake the sense that we’re drifting away from our liberal roots. Fringes on both sides are rejecting the liberal principle that all human beings are created equal and that our differences are dwarfed by our shared humanity. On the left, prominent activists are endorsing the idea that people with different immutable characteristics (race, gender, etc.) have different intrinsic worth. For instance, in 2021, Yale University’s Child Study Center hosted a psychiatrist who gave a speech titled, “The Psychopathic Problem of the White Mind,” where she compared white people to “a demented violent predator who thinks they are a saint or a superhero.” In response to Hamas’ brutal attack on Israeli civilians on October 7, Yale professor Zareena Grewal tweeted, “Settlers are not civilians. This is not hard.” Across the political aisle, Dilbert comic creator Scott Adams called black Americans a “hate group” whom white Americans should “get the hell away from.”

If a core component of political liberalism is that all human beings are created equal, then many prominent voices are pushing us rapidly toward an illiberal worldview where one’s worth is determined by immutable characteristics.

Increasingly, members of both parties seek to change liberal institutions to lock the opposition out of power. Their apparent goal is to undermine a key outcome of political liberalism: a peaceful and regular transfer of power between large and well-represented factions. On the right, prominent Republicans have refused to concede Trump’s loss in 2020, and many are refusing to commit to certifying the 2024 election should Trump lose again. “At the end of the day, the 47th president of the United States will be President Donald Trump,” Senator Tim Scott (R-SC) said in response to repeated questions about whether or not he would accept the election results. On the left, prominent Democrats advocate for abolishing the Electoral College, partly on the grounds that it favors Republicans; and for splitting California into multiple states to gain more blue Senate seats. Senators Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Tina Smith (D-MN), among others, have called for expanding the Supreme Court explicitly so they can pack it with Democrats.

This disdain for democratic norms isn’t limited to political elites on right or left; it is permeating the general populace. According to a 2023 poll, only 54 percent of young Americans (aged 18-29) agree with the statement, “Democracy is the greatest form of government.”

Economic liberalism is also under attack. In 2022, Pew found that only 57 percent of the public had a favorable view of capitalism. Those numbers are even worse among young Americans; only 40 percent among those aged 18-29 had a positive view of capitalism. By contrast, 44 percent of the same age group reported having a positive view of socialism. Faced with the choice of which system we should live under, it’s unclear whether young Americans would prefer economic liberalism over the command-and-control systems of socialism or communism. And while young people typically hold more left-of-center views and often become more conservative as they age, the intensity of young peoples’ opposition to capitalism should not be discounted. From 2010 to 2018, a separate Gallup poll found that the number of young Americans (aged 18-29) with a positive view of capitalism dropped by 23 percent.

Epistemic liberalism is on the ropes too. As the Harper’s Letter warned, “The free exchange of information and ideas, the lifeblood of a liberal society, is daily becoming more constricted.” In recent years, even prominent intellectuals have been terrified of being canceled for daring to write outside of the lines set by a new and predominantly left-wing orthodoxy, adversely affecting out discourse. Again, this disdain for liberalism is more acute among young people: a 2019 survey found that 41 percent of young Americans didn’t believe that the First Amendment should protect hate speech. Furthermore, a full majority (51 percent) of college students considered it “sometimes” or “always acceptable” to “shout down speakers or try to prevent them from talking.”

As Jonathan Rauch argues in The Constitution of Knowledge, a necessary precondition of epistemic liberalism is that everyone should be allowed to speak freely, a precondition increasingly unmet in recent years.

In their book Is Everyone Really Equal?, Robin DiAngelo (of White Fragility fame) and Özlem Sensoy even challenge the foundation of epistemic liberalism itself: the scientific method. This method mandates that hypotheses be tested against reality before acceptance. “Critical Theory developed in part as a response to this presumed infallibility of scientific method,” they write “and raised questions about whose rationality and whose presumed objectivity underlies scientific methods.” Of course, once we jettison the principle that ideas should be tested by holding them up to reality, all we have left are mythologies and accusations. One of the great triumphs of the Enlightenment was giving us the scientific tools to more accurately understand the world, but those tools—like other facets of liberalism—are increasingly under attack.

So, what went wrong? Why do so many Americans, particularly young Americans, harbor such disdain for our liberal order? Why have we seen the rise of widespread social censorship, and why do books telling us that not all humans are created equal become mega-bestsellers? We believe a key reason is that too many proponents of the liberal order (ourselves included) have failed to defend our ideals vigorously. In the face of our complacency, a small but impassioned minority intent on dismantling the pillars of liberalism has been gaining ground, both within institutions and within the hearts and minds of the younger generation.

Why haven’t many of us stood up for our ideas? We posit two reasons. First, there is a sense of complacency: a lot of us look at illiberalism and think, “It can't happen here.” The United States was founded as an essentially liberal country. We were the first country to really seek to embody Enlightenment ideals (however imperfectly) from our birth. Throughout our 250-year history, despite fluctuating levels of government intervention in Americans' social and economic lives, we have never lost our political, economic, or epistemological liberal foundations. This long track record of resilience has led many of us to overlook the rising threat of illiberal ideals, assuming our liberal system is too robust to be torn down.

Adding to this complacency is the fact that many threats to our liberal social contract are largely invisible to those outside educational or academic circles. Cloaked in the guise of combating racism, Critical Race Theory takes aim at the liberal order; however, most people who haven’t been inside the halls of a university in the last 10 or so years may not be aware of this aspect. Critical Theory—including Critical Race Theory, Queer Theory, Post-Colonial Theory, and others—generally opposes Enlightenment thinking, but its arguments are wrapped in jargon and mostly live in academic papers. For example, the book Is Everyone Really Equal? criticizes political, economic, and epistemic liberalism, but it’s not a mainstream bestseller; instead, it’s a widely-used textbook for prospective teachers. What begins in the academy often seeps out into schools and eventually permeates the broader society, and many teachers and professors of these ideologies explicitly describe themselves as activists or as scholar-activists whose goal is to turn the next generation onto these ideas. The threat is real, but the more anti-liberal facets of these ideologies aren’t exactly being shouted by CNN, which makes it easy to miss.

Second, as humans, we often abandon our ideals in the face of social pressure. Consider an organization consisting of ten people: one progressive and nine moderates. In 2020, each member starts to hear about Black Lives Matter (BLM). The progressive enthusiastically supports BLM, and loudly encourages his colleagues to do the same. What happens next illustrates how prone we are to jettison our ideals if doing so brings social rewards.

The first moderate faces a choice. He could thoroughly research BLM by investigating police violence nationwide, examining the evidence of systemic racism or system-wide equality, exploring BLM’s proposed program and what they actually advocate for, and making an informed decision about whether or not he supports the organization. But that’s a lot of work for not a lot of return. After all, his job doesn’t require that he understand BLM; the only immediate consequence is his colleague’s opinion of him. Consequently, he engages in what Nobel Prize winning economist Daniel Kahneman calls “substitution.” As Kahneman explains in Thinking, Fast and Slow, “when faced with a difficult question, we often answer an easier one instead, usually without noticing the substitution.” For example, when participants were asked how much money Exxon should pay for nets to prevent birds from drowning in oil ponds, they did not perform an economic calculation. Instead, what drove their decision-making process was emotion: “the awful image of a helpless bird drowning, its feathers soaked in thick oil.”

Thus, the moderate engages in substitution. Instead of tackling the complex and difficult question “What do I think of BLM?” he asks himself an easier but more emotional question: “How much do I care about black people?” For any decent person, the answer is “quite a lot”—and so he signs on with his progressive colleague. The fact that he’s now supporting an illiberal ideology—one of BLM’s co-founders said in 2019 that “I believe we all have work to do to keep dismantling the organizing principle of this society"—never occurs to him.

When the next moderate is asked the same question about whether he supports BLM, he has the same incentive as his colleague to engage in substitution, but with added social pressure: now two of his nine coworkers support BLM, and he risks losing social capital if he does not. As humans, we are social animals. Sociologist Brooke Harrington explains that we often value others’ perception of us more than our own survival, as social ostracism in our distant past often meant death anyway. As she puts it, “social death is more frightening than physical death.” And so, motivated by the social rewards for supporting BLM and the fear of social punishment if he does not, one coworker after another agrees to support BLM.

Adding to our social calculus is the fact that we all want to be seen as (and, even more importantly, see ourselves as) empathetic. In the example of BLM, we don’t want to be perceived as racists. If this means going along with an organization that says that police “cannot [be] reform[ed]” because they were “born out of slave patrols,” then that’s a small price to pay. This same desire to be seen as empathetic (again, especially by ourselves) holds when we are called to cancel a professor for saying something insensitive, or to condemn cultural appropriation, or to read and praise books and articles claiming that liberalism has failed marginalized people and that a new, totalitarian system is necessary for their salvation.

But why shouldn’t we be complacent? Why shouldn’t we go along to get along, and let our values bend here and there so we can fit in with the new illiberal crowd? One reason is that the stakes are no longer trivial. There is nothing magical about the liberal order that guarantees it will always triumph. History shows us that liberalism can give way to totalitarianism, as it did in Nazi Germany; or to empire, as in ancient Rome. In England, new rules regulate what people are allowed to say, with citizens facing fines or imprisonment for saying something the political establishment does not like. In Canada, a new bill supported by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau would criminalize speech that those in power consider hateful. The United States is not immune to these dangers. Our Constitution alone is not a sufficient defense, because laws are downstream from culture. The Constitution and the Bill of Rights can be interpreted by illiberal justices (and have been in the 20th century); and when this happens, our rights can erode very rapidly indeed. Our freedom is sustained not by our geography or even our founding documents, but by our willingness to fight for liberalism—to defend it in the court of public opinion.

If we’re going to preserve the freedoms we cherish, that is what it will take. We must find the courage to stand up for our ideals—to speak and act based on principle alone. We must be open to new evidence that might change our views, but at the same time resist having our minds changed for us. We must prioritize truth over popular opinion.

In essence, we must think and act more like August Landmesser.

[ Source: The Lone German Man Who Refused to Give Hitler the Nazi Salute (businessinsider.com) ]

--

About the Authors

Julian Adorney is the founder of Heal the West, a Substack movement dedicated to preserving our liberal social contract. He’s also a writer for the Foundation Against Intolerance and Racism (FAIR). Find him on X: @Julian_Liberty.

Mark Johnson is a trusted advisor and executive coach at Pioneering Leadership and a facilitator and coach at The Undaunted Man. He has over 25 years of experience optimizing people and companies—he writes at The Undaunted Man’s Substack and Universal Principles.

==

Whatever its flaws, every alternative to liberalism is a nightmare.

#Julian Adorney#Mark Johnson#liberalism#liberal values#liberal ethics#liberal society#secularism#secular liberalism#classic liberalism#Enlightenment#Enlightenment values#The Enlightenment#political liberalism#economic liberalism#epistemic liberalism#epistemology#religion is a mental illness

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

While Keith merely seemed like “a Teddy Boy who'd spit in his beer to ensure nobody drank it” and had “no plans to work,” and Brian regarded music as an irreplaceable vocation, Mick talked often of becoming a lawyer or perhaps a journalist, as the LSE graduate Bernard Levin had done with spectacular success.

Philip Norman, Mick Jagger.

#keith richards#mick jagger#brian jones#the rolling stones#classic rock#old rockstar#book quotes#quotes#60s rock#sixties#60s music#60s era#60s#1960s#rocknroll#rock#rock n roll#r&b music#rock band#r&b#Philip Norman#LSE#london school of economics#bernard levin

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

green venom dice. Transperant dice with green smoke suspended inside.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A little fun fact about me is that back when I was a cringy ah 12yo I’d sometimes add really random tags that had absolutely no relation to the subject matter of my main post. Just for the shits and giggles.

And to annoy people and for attention ofc (can you tell I’m unemployed yet?)

Let’s see how many we can fit with this one (this is the only one I promise lol)

#whale watching#bdsmkink#the crown#classic literature#stray kids#astro photography#egyptology#sanrio#audhd#sovietwave#colonialism#merry x eowyn#alcohlism#rush e#sedimentary rock#gen z nostalgia#botany#disgusting#big pharma#shitpost#recipes#hells kitchen#barbenheimer#water cycle#economics#girl dinner#capri sun#football#anti work#doggo

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

what do you plan to do with your degree after uni?

FUCK NASTY!!!

#if i ever touch economics again it's a cry for help like i cannot stress enough how fucking pointless this degree is gonna be#okay deep breath im only being so negative bc im balls deep in exam season. it's a GOOD degree i DONT REGRET MY DEGREE#this will be EXCEPTIONALLY helpful when i go into the working world i am EMPLOYABLE bc of my DEGREE#like economics is a VERY versatile subject there arent many areas of work that econ doesnt apply to in some way#so i KNOW it's a really good degree to have and i can kinda do what i want afterwards#but oh my fucking god. jesus christ. bloody fucking hell#i do however know that in the immediate year after my degree im gonna move back home and waitress full time#bc i just need to like. take some time off education and recover LMAO and i want a space to just tick some boxes i never got round to#like learning how to drive and stuff. and living without having rent to pay in a place im very familiar with will be good#even if i do think it's gonna have it's own struggles. oh hometown blues we're really in it now#but yeah after that year im thinking about maybe doing a masters? but ill have to proper blag it bc you typically have to do#masters in subjects relevant to your degree and i dont want to go within a radiation exclusion zone of economics#so. there's that. do u think if i say please somewhere will let me do a classics masters be honest. if i say pretty please#ask#hella goes to uni

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s difficult to estimate with any precision the volume of trade flowing between Rome and Gaul. But the number of shipwrecks found off the Gaulish coast surges after 150 BC, peaking at about 100 BC. This suggests an exponential rise in the volume of trade over that half century.

For the most part, the vessels’ cargos were dominated by wine. The Madrague de Giens wreck was carrying around 7,000 amphorae when it sank off Hyères (south-eastern France) in about 50 BC. The quantity of amphorae discovered on the wreck suggests that the annual export of wine to the Gauls had reached about 100,000 hectolitres a year by the first century BC – a volume that would have generated about 40 million amphorae over the century. It is hardly surprising, then, that the Roman stereotype of a Gallic man was of a drunkard slurping wine through his long, drooping moustache.

The wine was transported along two major trade routes. One started at Narbo (modern-day Narbonne, founded in 118 BC), snaked along the river Aude and then overland to Tolosa (Toulouse) on the Garonne. The other travelled up the Rhône to Cabillonum (Chalon-sur-Saône) in the territory of the Aedui.

From these major transhipment centres, the wine was then taken into Gaulish territory to the principal settlements within easy reach of the frontier – places such as Bibracte, Jœuvres, Essalois and Montmerlhe. Roman traders may well have been resident in these native centres to oversee the exchanges. There were certainly Italian merchants in Cabillonum as late as 52 BC. These men were charged with ensuring a steady flow of slaves to markets in a bid to meet the Roman estates’ demand for a staggering 15,000 Gaulish slaves every year.

— The Celts: were they friends or foes of the Romans?

#barry cunliffe#the celts: were they friends or foes of the romans#history#classics#economics#trade#commerce#transport#maritime history#food and drink#alcohol#archaeology#slavery#ancient rome#gaul#roman gaul#celts

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cathonomics & Integral Ecology - Treating People and the Environment with Inherent Dignity

Cathonomics & Integral Ecology – treating people and the environment with inherent dignity – Faith & Reason lecture – March 30th, 2023

*NOTE: this event had to be rescheduled due to severe winter weather. The event will now be virtual and take place on March 30th.

Description:

“The main tenets of socialism, community of goods, must be utterly rejected, since it only injures those who it…

View On WordPress

#Anthony Annett#Capitalism#Catholic Conscience#Catholic Social Teaching#Catholic Third Way#Catholicism#Cathonomics#Christine Lagarde#Classical Economics#Climate#Climate change#Columbia University#Conservative#Economics#Environment#Environmental science#Environmentalism#European Central Bank#European Union#Fordham University#Free Market#Georgetown University#Homo-economicus#Ideology#Integral Ecology#Integral Human Ecology#International Development#International Monetary Fund#Jeffrey Sachs#Justice

0 notes

Text

Having the time of my life thinking about what final year high school subjects the ROs took/would’ve taken given the chance.

Ernestine would’ve 100% been a psych girl and would fight you to the death if you tried to say psychology isn’t a science

#she would’ve also taken legal studies maths and economics#Otto did PE and all the arts subjects#lemon sorbet would’ve taken drama dance theatre studies and food science#no wait#he would’ve taken philosophy too#gil did all the sciences + maths and classics#Eddie took psych history geography and language#and physics#and also PE#ros

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

47: True…

#The tough economic realities of both the real world and the Splatlands were key influences in the Money Fame Love Splatfest#but you lot aren’t ready for that conversation#splatoon#splatoon 3#splatnet#my motherfuckin’ queue tag#a certified themainspoon classic

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

for reasons unknown to me, I was reading an right-wing essay that is attacking the CLT, or Classical Learning Test (a sorta-alt-righty christian nationalist rejiggering of the SAT, recently mandated for Florida teenagers) for being too woke and insufficiently white.

The whole essay is a trip, which I'm not gonna get into, but part of the author's point is that the classics (by which he means variously all sorts of European writing from roughly 1000BC-1600 CE) are incompatible with the values of the modern left. Which, sure, okay, that's an interesting argument. Don't know if it's true, but it's interesting.

But as an example, the author writhes:

"The poem from whose shadow the classical tradition can never escape is The Iliad... [In contrast to modern ideas about equality] it is a hymn to the excellence—the virtue—of a hero whose power surpassed that of a whole generation of heroes.

Achilles and Odysseus alike—the two epic heroes, found no way to live as heroes worthy of worship while avoiding death."

Now, I'm no classicist, but I'm pretty darn sure that the take away from "sing the rage of Peleus’ son Achilles/ murderous, doomed, that cost the Achaeans countless losses/ hurling down to the House of Death so many sturdy souls/ great fighters’ souls, but made their bodies carrion..." is not oh wow Achilles was such an upstanding dude deserving of worship!

#not to mention the ridiculousness of saying: “oh classics can't be read from a leftist framework”#when by your own admission “the classics” covers a whole host of different writing across over 2000 years#hundreds of distinct cultures#multiple differing economic systems#and at least 4 different mainstream religions#classics#alt-right#white nationalism#Classical learning test#fuck desantis

3 notes

·

View notes