#Plot Structure

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Me, infodumping about all the characters, plot points and intricate plot twists to my friends: *writing at 10000 words per second* Me, actually trying to write the story: *staring at a blank word document for 3 hours* Do you have a cure for such a condition?

It gets a lot of flack (not unjustified), but the Save the Cat Beat Sheet is truly great for figuring out how to get a plot on paper. You do not have to follow it to the letter, but it does give you definite goals to meet when trying to figure out where to go next.

Other popular plot outline structure's include:

Dan Harmon's Story Circle

The Snowflake Method

The Hero's Journey

Dan Wells' 7-Point Structure

And many mooooooore. Any plot structure that works for you is great, but keep in mind, you might have to try out more than one.

Save the Cat worked great for me and that's what I recommend the most, but my final draft isn't rigidly structured to its beat sheet. What I really needed was a starting point, and once I got a first draft down, I was able to figure out where to go.

269 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's talk about story structure.

Fabricating the narrative structure of your story can be difficult, and it can be helpful to use already known and well-established story structures as a sort of blueprint to guide you along the way. Before we delve into a few of the more popular ones, however, what exactly does this term entail?

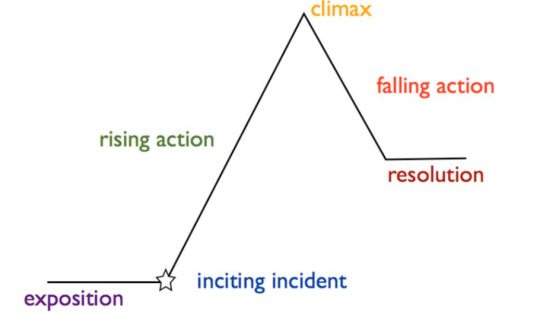

Story structure refers to the framework or organization of a narrative. It is typically divided into key elements such as exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution, and serves as the skeleton upon which the plot, characters, and themes are built. It provides a roadmap of sorts for the progression of events and emotional arcs within a story.

Freytag's Pyramid:

Also known as a five-act structure, this is pretty much your standard story structure that you likely learned in English class at some point. It looks something like this:

Exposition: Introduces the characters, setting, and basic situation of the story.

Inciting incident: The event that sets the main conflict of the story in motion, often disrupting the status quo for the protagonist.

Rising action: Series of events that build tension and escalate the conflict, leading toward the story's climax.

Climax: The highest point of tension or the turning point in the story, where the conflict reaches its peak and the outcome is decided.

Falling action: Events that occur as a result of the climax, leading towards the resolution and tying up loose ends.

Resolution (or denouement): The final outcome of the story, where the conflict is resolved, and any remaining questions or conflicts are addressed, providing closure for the audience.

Though the overuse of this story structure may be seen as a downside, it's used so much for a reason. Its intuitive structure provides a reliable framework for writers to build upon, ensuring clear progression and emotional resonance in their stories and drawing everything to a resolution that is satisfactory for the readers.

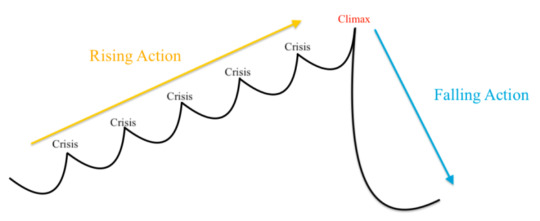

The Fichtean Curve:

The Fichtean Curve is characterised by a gradual rise in tension and conflict, leading to a climactic peak, followed by a swift resolution. It emphasises the building of suspense and intensity throughout the narrative, following a pattern of escalating crises leading to a climax representing the peak of the protagonist's struggle, then a swift resolution.

Initial crisis: The story begins with a significant event or problem that immediately grabs the audience's attention, setting the plot in motion.

Escalating crises: Additional challenges or complications arise, intensifying the protagonist's struggles and increasing the stakes.

Climax: The tension reaches its peak as the protagonist confronts the central obstacle or makes a crucial decision.

Falling action: Following the climax, conflicts are rapidly resolved, often with a sudden shift or revelation, bringing closure to the narrative. Note that all loose ends may not be tied by the end, and that's completely fine as long as it works in your story—leaving some room for speculation or suspense can be intriguing.

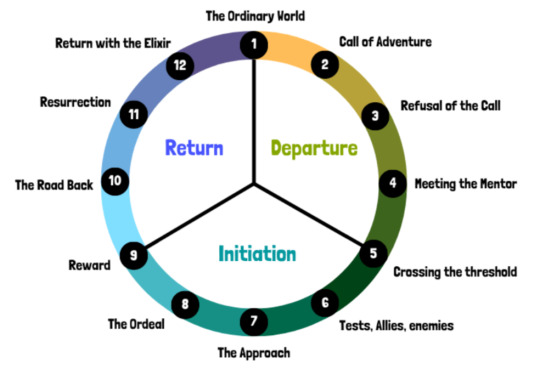

The Hero’s Journey:

The Hero's Journey follows a protagonist through a transformative adventure. It outlines their journey from ordinary life into the unknown, encountering challenges, allies, and adversaries along the way, ultimately leading to personal growth and a return to the familiar world with newfound wisdom or treasures.

Call of adventure: The hero receives a summons or challenge that disrupts their ordinary life.

Refusal of the call: Initially, the hero may resist or hesitate in accepting the adventure.

Meeting the mentor: The hero encounters a wise mentor who provides guidance and assistance.

Crossing the threshold: The hero leaves their familiar world and enters the unknown, facing the challenges of the journey.

Tests, allies, enemies: Along the journey, the hero faces various obstacles and adversaries that test their skills and resolve.

The approach: The hero approaches the central conflict or their deepest fears.

The ordeal: The hero faces their greatest challenge, often confronting the main antagonist or undergoing a significant transformation.

Reward: After overcoming the ordeal, the hero receives a reward, such as treasure, knowledge, or inner growth.

The road back: The hero begins the journey back to their ordinary world, encountering final obstacles or confrontations.

Resurrection: The hero faces one final test or ordeal that solidifies their transformation.

Return with the elixir: The hero returns to the ordinary world, bringing back the lessons learned or treasures gained to benefit themselves or others.

Exploring these different story structures reveals the intricate paths characters traverse in their journeys. Each framework provides a blueprint for crafting engaging narratives that captivate audiences. Understanding these underlying structures can help gain an array of tools to create unforgettable tales that resonate with audiences of all kind.

Happy writing! Hope this was helpful ❤

Previous | Next

#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing advice#writing help#writing resources#creative writing#story writing#storytelling#story structure#plot development#outlining#plot structure

496 notes

·

View notes

Text

Three Act Structure: what's your favorite part?

Act one – Setup. This act lays the groundworks for the story and leads up to the inciting incident (the 'thing' that truly starts the gears of the story). Who are the characters? What world do they live in? What stakes are at play? For example, in the LOTR movies (poll is NOT about LOTR specifically): the introductory monologue all the way up to the Council of Elrond.

Act two – Rising Action & Confrontation. Tensions heighten as the characters are working to reach the goal as set out in act one. It ends with the climax, where the goal is either reached or not. In the LOTR movies: Council of Elrond up until the One Ring is cast into the fire.

Act three – Resolution. Everything that happens after the climax. In what kind of world/state are the main characters left? What happens next?

As an example, consider the Lord of the Rings series:

Act I: Everything from the beginning monologue up until the Council of Elrond

Act II: The Council of Elrond up until the One Ring is cast into the fire.

Act III: Everything after the One Ring is cast into the fire.

–

We ask your questions so you don’t have to! Submit your questions to have them posted anonymously as polls.

#polls#incognito polls#anonymous#tumblr polls#tumblr users#questions#polls about interests#submitted june 20#stories#storytelling#story structure#plot structure#plot#fiction#reading#books

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

Question for fellow writers

(Especially if you struggle with demand avoidance or similar issues)

Is “Save the Cat” ACTUALLY good?

Look, I know, everybody recommends it. The writing craft has rules and structures that work for a reason.

That being said, everybody recommending it makes me not want to pick it up. Why would I want to follow the exact same beat pattern as everybody else? I feel like this is why some books lose unique feelings in terms of structure and set up.

Logically, I don’t recognize that issue as much as a reader. As a writer, my brain just can’t get past the hurdle.

I feel like personal, specific opinions and advice will help me to either get over the feeling (or feel justified, depending on the response).

Any and all responses would be lovely! Tell me if it’s amazing, if I’m thinking of it too literally, or if it’s not something you enjoy at all.

#writeblr#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#writer stuff#writer problems#writers and poets#writer things#writing#writing craft#save the cat#plot structure#plot beats#plotter#pantser#discovery writing

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've spent several days compiling some notes for myself on story structure and scene structure mostly derived from this website's blog posts, thought I'd share the final product which can be used as a base scaffolding to outline a story onto.

Here is a link to download the document version, and I'll also include a full text post version under the readmore.

Protagonist

What do they want? (May be tied to their Ghost, a motivating factor in their backstory)

What do they actually need to achieve? What is The Story Goal?

What is The Lie They Believe (arises from their backstory weakness/wound/ghost) which constricts their ability to move forward effectively towards the story goal? -- A Pain Point in their past/personality that contributes to the inner conflict and drives the character arc. A flaw in their perspective or worldview that has served to protect them from the wound of their past so far.

(Optional) Deuteragonist

What do they want?

The Lie They Believe

What do they actually need? And how does it align with The Story Goal?

Antagonist/Opposing Forces/Source of Conflict (Obstacles that prevent protagonist from achieving Story Goal)

What do they want?

What are the main obstacles they put between the hero(es) and the story goal?

Theme (tied to character progression)

What is your main character’s internal conflict?

What is the lesson, or Truth your characters learn or fail to learn by the end of the story? (what changes in them between inciting incident and climax?)

How will the main character demonstrate their changed views?

What symbols or motifs reinforce or represent the theme and the character’s attitudes toward it?

Major Plot Points and approximate locations in the narrative. Each of these important Plot Point scenes/scene sequences have two distinct halves.

The main elements/beats of the story mirror each other across both halves.

The midpoint is the hinge/swivel point that turns the entire story.

Beginning to midpoint, the protagonist primarily reacts.

Midpoint to ending, the protagonist primarily acts.

Act I

Hook - Mirrors Resolution

Set Up – Establishes Normal World

Introduces characters, their story goals, the Lie the main character believes, and the stakes.

External factors and plot events that will influence protagonist enter play

Establishes foundational problems and mindsets, the need for something to Change

Inciting Event – Call To Adventure and Refusal of the Call

Turning Point of Act I

Mirrors and Foreshadows Climactic Moment - asks a question which will be answered in the climax

The first time the story brushes up against the main conflict, the Normal World is rocked by conflict, but the protagonist is not yet irretrievably involved in the plot

A. Call To Adventure

Positive/forward value – scene goal

The story reaches a crossroads

The protagonist is offered a choice

Dramatic and potentially life changing, either good or bad

B. Refusal of the Call

Negative value – scene disaster

The protagonist cannot fully accept the call immediately

The call can be resisted by the protagonist or by another character warning them of consequences, or by an obstacle that prevents their immediate acceptance

Build-Up –

the final pieces of the main conflict are moved into position

tension is ramped up

1st Plot Point - Key Event and Door of No Return

transition/threshold from Act I to Act II, from Normal World to Adventure World, locks the Protagonist into Conflict

Mirrors and Sets up/foreshadows 3rd Plot Point

Big Set Piece Sequence and Paradigm Shift

A. Key Event

The protagonist engages with the conflict for the first time by choice

the event/conflict may seem to be out of their control, but the protagonist must choose to act

Reversing Position from the Refusal of the Call

B. Door of No Return

Consequences of the choice to engage with conflict

Closes the door to Normal World and forces Protagonist into Adventure World. No turning back now.

Act II

First Half of Act II – Reaction

Establish Reaction –

Protagonist responds to First Plot Point

scrambles to understand the new obstacles from the antagonist

they currently lack sufficient understanding

First Pinch Point– Turning point of first half of Act II, mirrors second pinch point

Reminder of the power of the antagonist,

provides new clues about the conflict and foreshadows

sets up a conflict which comes back in the second pinch point.

Realization –

Protagonist's revelation grows

reactions become more informed

previous failures are building towards understanding The Truth

2nd Plot Point - Midpoint - Plot Reversal and Moment of Truth

Turning Point of the Entire Narrative

Big Set Piece Sequence and biggest paradigm shift

Protagonist moves from reactive to truly active

The Protagonist learns of The Truth

Internal and External conflicts collide

A. Plot Reversal

External Conflict

Protagonist is given paradigm shifting information

B. Moment of Truth

Internal Conflict

A new internal understanding arises

Second Half of Act II – Action

Establish Action –

Thanks to their new understanding, the protagonist makes headway against the antagonist.

They have yet to fully accept The Truth and reject The Lie and are trying to act within both paradigms of The Truth and The Lie.

This sets up what will become the disastrous low point of the 3rd Plot Point

Second Pinch Point –

Turning point for second half of Act II.

Follows from what was set up in First Pinch Point. Foreshadows 3rd Plot Point.

Serves to remind the protagonist what is at stake.

Renewed Push Towards Seeming Victory –

Protagonist renews attack on antagonist.

ACT III

3rd Plot Point - Seeming Victory and Reversal of Fortune

Transition/Threshold from Act II into Act III

Big Set Piece Sequence and paradigm shift

Mirrors 1st Plot Point

End of internal conflict

The protagonist either fully rejects The Lie and successfully resolves their internal conflict setting the stage for Victory, or fails to reject The Lie and sets the stage for their Failure

A. Seeming Victory

May be a false victory or a partial victory with unforeseen consequences

B. Reversal of Fortune (Low Point)

Represents death, can be an ego death, can be an actual death or other catastrophe

the worst thing that could have happened up to this point

These are the consequences of maintaining The Lie

The protagonist must “Die” in The Lie in order to live in The Truth

Recovery –

Reaction to the low point of the 3rd Plot Point

Protagonist reels, questions his choices, worth, ability, and commitment to goals

Turning Point –

Begins Climax scene sequence.

The protagonist and antagonist finally face each other.

Confrontation –

(metaphorical or otherwise) Duel to the death

The protagonist and antagonist cannot both walk away from this.

Climactic Moment

Mirrors the Inciting Incident to bring the narrative full circle

The moment the protagonist meets their story goal, the external conflict can no longer continue and is resolved

External conflict results in either Victory of Failure based on whether or not the hero was able to Reject The Lie and Accept The Truth in the 3rd Plot Point

A. Sacrifice -

The protagonist must be willing to sacrifice something huge to achieve their goal

B. Victory/Failure -

Whether the protagonist reaches a Victory or Failure depends on the outcome of the 3rd Plot Point and the direction of their character arc

Resolution – Mirrors the hook. Eases readers out of the high of the climax and into the final emotion. Return to a New Normal changed by the events of the narrative.

Dan Harmon Story Circle – another way of visualizing story structure

Scene Structure

The structure of a scene mirrors the structure of the story overall, beginning (introduces conflict) middle (Tension rises, actions are taken) and end (climax of conflict). Just as there is a story goal driving the entire character arc of the story, each scene has a scene goal driving the arc of the scene.

Each Scene divides into two halves, action (scene) and reaction (sequel)

In the scene/action Stuff Happens, in the sequel/reaction characters Reflect on What Happened and find their new direction before the next Scene

The reaction doesn’t have to be as long as the action but it is necessary for the pacing and advancement of character and story to have it, even briefly.

A full Scene must have a reversal of emotional states. The character must start a scene feeling one way and end the scene feeling another.

You can of course mix up the order and presentation of scene and sequel depending on story needs and artistry, reducing either a scene or a sequel to summary in narration or playing with the order the beats are presented.

Multiple scenes can chain together into a scene sequence around a shared concept

For Example, a scene sequence of characters traveling to a place to do a thing may include a scene where they figure out transportation, a scene where they travel, and a scene where they arrive and orient to their ultimate goal.

Two Halves of a Scene, each with three parts

Action (scene) - Goal, Conflict, Disaster

Reaction (sequel) - Reaction, Dilemma, Decision

Action

1. Scene Goal for character(s)

Wants:

Something concrete (an object, a person, etc.).

Something incorporeal (admiration, information, etc.)

Escape from something physical (imprisonment, pain, etc.).

Escape from something mental (worry, suspicion, fear, etc.).

Escape from something emotional (grief, depression, etc.).

Methods:

Seeking information.

Hiding information.

Hiding self.

Hiding someone else.

Confronting or attacking someone else.

Repairing or destroying physical objects

2. Conflict

Options:

Direct opposition (another character, weather, etc., which interferes and prevents the protagonist from achieving his goal). Inner opposition (the character learns

something that changes his mind about his goal).

Circumstantial difficulties (no flour to bake a cake, no partners to dance with, etc.).

Active conflict (argument, fight, etc.).

Passive conflict (being ignored, being kept in the dark, being avoided, etc.)

Generalities:

Physical altercation.

Verbal altercation.

Physical obstacle (weather, roadblock, personal injury, etc.).

Mental obstacle (fear, amnesia, etc.).

Physical lack (no flour to bake a cake).

Mental lack (no information).

Passive aggression (intentional or unintentional).

Indirect interference (long-distance or unintentional opposition by another character).

3. Disaster or Achievement of Scene Goal

Options:

Direct obstruction of the goal (e.g., the character wants info which the antagonist refuses to supply).

Indirect obstruction of the goal (e.g., the character is sidetracked from achieving the goal).

Partial obstruction of the goal (e.g., the character gets only part of what he needs).

Hollow victory (e.g., the character gets what he wants, only to find out it’s more destructive than helpful.)

Suggestions:

Death.

Physical injury.

Emotional injury.

Discovery of complicating information.

Personal mistake.

Threat to personal safety.

Danger to someone else

Reaction/Sequel

4. Reaction (relay emotions)

Emotions:

Elation.

Fury.

Anger.

Confusion.

Despair.

Panic.

Shame.

Regret.

Shock.

How to relay:

Describe

Internal narrative/monologue

Dramatization

Tone

5. Dilemma

Phases:

Review

Analyse

Plan

Options:

Implicit

Explicit

Summary

Dramatization

6. Decision

Options:

Take action

Don’t take action

Long-term goal, short-term decision

Do they come to an obvious decision or take a longshot?

Establishes new different scene goal for next scene, see Scene Goal for options.

#I know some people don’t like to try and do structure too much by the book but I personally find this helpful so#writing#storycraft#writing reference#writing advice#plot structure#caitie speaks

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have a thought, about character creation. I hesitate to claim this thought is some sort of advice, it's just a thought, though I think it merits further exploration and practice to see how it goes. The thought is this:

I think sometimes, when a writer struggles to actually sit down and write, but has a lot of OCs, it's because you think of your characters too much as people. I think some people struggle to tell stories because they are more interested in coming up with people.

Let me elaborate.

I've always been very focused on character creation as the foundation of good writing. When I was younger, and just starting to write, I remember someone proposing the question - which is more vital to creating a good story - a strong plot, or a strong character? At the time, I answered strong characters, hands down. My argument was that a strong character can still carry a weak plot, but a strong plot can still be boring af if the characters are weak. I do still see some merit to that line of thinking.

When it comes to actually writing down my stories, though, I've always really struggled with first drafts. I would fill notebook after notebook with detailed notes on plot points, worldbuilding, and most of all, on characters. Elaborate backstories, personality breakdowns, strengths and weaknesses, hopes and dreams and fears and every other thing that you've seen on a character profile template. I would take my time with things like choosing names, and I would flesh out their families and the people around them because to know their relationships is to know them. I've been protective of my characters, cherishing them, as many of us do, as if they were my children, as if they were dear friends of mine.

But I have yet to complete any long form projects. I have yet to complete any rough drafts for novels. When I was younger, it was because I was determined to do my stories justice. I was determined to do my beloved OCs justice. I didn't feel my writing was strong enough so I just... didn't write for my original works. I would play around with fanfiction, and I read a lot, and eventually I got into writing RP. But I didn't do anything concrete with my OCs beyond making plans for their stories.

Then I entered a short story contest — NYCMidnight's short story contest. They go in four rounds, and give you a prompt, a word limit, and a time limit in which to write your story. You get a week and 2500 words for round 1, three days and 2000 words for Round 2, two days and 1500 words for Round 3, and 24 hours and 1250 words for Round 4. The first year I participated, I went 3 rounds before being knocked out. Last year, I wrote for the first 2.

Which means I've produced five completely original short stories for the prompts given. I was absolutely shocked by how productive I was in such a short span of time. You are given your prompt the moment your clock starts ticking for each round, so you don't have time to prepare ahead. Which means that not only did I have to come up with a plot very quickly, I was also creating characters on the spot.

When you have three days to write a story, you can't spend months carefully crafting a character. So when it came to drafting, I just started slapping very quick characters together that could do what was needed for the plot. My prompt is genre: ghost story, character: a best man, and subject: temporary? Okay, then I need a bride, a groom, a best man, and a ghost. My bride is (picking a random name) Victoria, she's checking out venues with her fiance, and she realizes the place they're checking out is haunted. And off we go.

And you know what? I figured out who Victoria is as I wrote. She's conflicted, she's on the verge of breaking things off. The ghost is reaching out to her, helping her come to terms with the end of her relationship. I didn't need to know her favorite color or her childhood trauma or her blood type to write the story. Some of those things might come out in the writing. Many of them just never become relevant.

Now, I'm not saying that character profiles are trash. I don't hold with blanket advice, and this isn't advice, remember, this is just a thought. But for me, doing these fast exercises even though I always had thought of myself as a planner not a pantser, showed me that I can still write a damn good story even without writing a novel's worth of notes and plans alone.

Getting back to the original thought... I guess what I'm trying to get at here is, sometimes I think authors can get so tangled up in the create-a-character stage, or the world-building stage, that we forget that we aren't meant to be writing a travel guide, or designing a fully-realized person.

At some point, you have to say okay, now lets put that person in some situations and see what they do. You gotta stick them in a scenario where they are not just spouting backstory at another character, but are making a choice. Okay, they have trauma. They have complex personalities. But what are they doing? What choices are they making and what waves are they making? That's where the plot comes from, and how you make it go. That's plot. And the plot is where the story happens. And you're just writing it all down as it goes, and that's your rough draft.

Every time i get stuck on a story, I instinctively reach for the background notes. I just need to know what makes them tick, I think, and that's how I'll fix it. But nine times out of ten, I don't, actually. That way leads to Not Writing (tm). And I still struggle with that more than I'd like for my bigger projects.

Trying (again) to bring it back to the initial thought... I just think it's interesting that the stories that were easiest to complete were ones where the characters were made up as I went along. I just wrote. Added new characters when needed. Oh, protag needs a friend to carry out a conversation? Guess we have a new character. They continue on their merry way, surprise, someone's stalking them, new character! Meanwhile the stories where I've outlined every character and know who each of them are, still sit unwritten.

That's not the sole factor in why a story has or hasn't been written out, mind you. It's more a comment on, if your OCs are too dear and you're taking too much time with designing them, you are losing valuable time that you could figure out who they are as you write their story. By you I really mean me. Or whoever might find this useful, I suppose.

Anyways. That's my thought. If anyone has any thoughts of their own about this, I'd love to hear them!

#on writing#writeblr#character-driven#plot-driven#plot-driven vs. character-driven#character profile#character design#character development#plot development#plot structure#plot#planner vs pantser#writer's block#rough draft#original characters#original story#project: tnvomd#my thoughts

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Tips: Save The Cat! Or the 15-Beat Plot Structure

ACT 1:

Introduction to the world, what is happening, what is the style.

Exposition, coincidences, information.

Who, what, where, when, why.

1. Opening Image

Short. Open by giving the reader questions that need answers. What is happening in this world.

2. Theme Stated

The theme is outright stated by one character to another. A tiny blurb stating what the character needs/is missing to grow.

3. Set Up

Many scenes. Explore what is in this world. Meet the main characters and what they need to grow. This ends with the inciting incident.

4. Inciting Incident

Usually before the 1/4 mark in the story. Interruption in the hero's normal life.

5. Debate

Slow, the hero reacts to the inciting incident. Reflection and contemplation by the hero.

ACT 2:

Escalating stakes and action.

6. Break Into Two

A deliberate decisive action by the hero. Visual shift: enter a new world.

7. B Story

Introduction of subplot. Introduction of a new character: 9/10 a love interest. New character that usually will push the hero into growing.

8. Fun And Games

Many scenes. Entertainment for the reader. Exploration of the world. Hero is grappling with the main conflict. If it is a bank heist movie, this is where the bank heist occurs.

9. Midpoint

Abrupt shift: take away what your hero cares for the most False victory or defeat. The battle is won, or we have screwed up and lost. Causes escalation of stakes: the battle is won, no wait, it isn't. Or, oh shit we screwed up, we have to regroup and find a way.

10. Bad Guys Close In

Escalation of stakes. Forces of antagonism is getting stronger and clearer.

11. All Is Lost

The lowest point for the hero. All is lost, nothing can be done, why are we even trying, we cannot win this.

12. Dark Night of the Soul

Slow scene. A mirror of the Debate beat. Moment to recover and make a new plan. Hero receives words of wisdom and source of hope. A council where everyone bickers.

ACT 3:

Most emotional moments.

Seeing the hero grow and resolve a conflict.

Escalation in pace and action.

No coincidences. Things happen because the hero make it happen.

No more new questions or conflicts. Things are being solved.

13. Break Into Three

Hero makes a choice and acts on it.

14. Finale

Last extended scene. Hero becomes who they need to become and face the threat. A critical choice is made and brings resolution.

15. Final Image

The final feeling for the reader. Farewell to the reader.

This is part of my Writing Tips series. Everyday I publish a writing tip to this blog.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

How I Plot

I often tell the story that I was unable to complete a book satisfactorily until 2019 when I first learned to plot. A lot of writers are allergic to this advice, thinking having a plot will kill their desire to write their story. This might be true for them, but there are also diverse levels of plotting, from detailed scene plans to a rough sketch of what you want to happen in your story. I am about 60% plotter, 40% pantser (or discovery writer). I have a main list of plot points and then kind of discover my way between them on a scene-by-scene level. But what do I mean by plot points, anyway? Is there a model that would help you construct that? I do have a strategy I use. There are many out there, this is just the one I’ve evolved that works best for me. I started with Dan Wells’ 7-point plot structure and tweaked it from there.

Every plot thread has nine main parts that I try to have a pretty good idea about. Here are the nine:

Opening – This establishes the status quo of the main characters at the start of the story. This is also where your story really begins. Some people add an exciting prologue to set the tone promises, but that is beyond the remit, and it is up to you whether or not you do that. The opening is the first part of the actual story, where you begin introducing your main characters and where they are in their lives.

Inciting Incident – Something happens that disrupts the protagonist’s status quo. This could also be a story goal being introduced. The story really gets started here, when the protagonist either starts working on the problem or must deal with whatever is happening to their lives.

Plot Point 1/Threshold 1 – T status of the story changes. There could be an escalation, a new venue introduced, but the story starts a different phase here. The protagonist’s life is much different now from when we met them in the opening.

Complication phase 1 – The problem gets worse, the goal gets further away, the protagonist’s solution blows up in their face, shit goes down. This can be a series of chapters or a series of scenes.

Midpoint – Probably the most important part of your story and should come as close to the middle of the book as possible. The Protagonist develops a new plan, another new venue is introduced, the antagonist’s attack, something major happens that turns the story in a new direction.

Complication Phase 2 – Just like complication phase 1, but more intense with higher stakes. The goals might seem further away, or they might seem impossible. There could be a development where the protagonist sees the glimmer of the plan, gathers their allies, etc. This gets, well, complicated. These things will be different based on the stakes of your book and your genre.

Plot Point 2/Threshold 2 – Sometimes called ‘the dark night of the soul,’ what happens here is dependent on your genre and stakes. In a romance, this is where the couple is separated, seemingly forever. But here the protagonist has been pushed to the breaking point. Maybe they’ve suffered a loss or an insurmountable setback. They have no clear plan and are left to gather the tools that are available to them and form a new one. They should also find some resolve here and this is where the stakes of the plot are underlined.

Climax – The main conflict comes to a head and is resolved in some way, whether in the protagonist’s favor or not. The ultimate battle, the reconciliation, the final overcoming of obstacles. In a mystery, this is where the villain is unmasked and confronted. This will be dependent on your genre and the conflicts that have been introduced. It looks vastly different depending on your genre.

Resolution – AKA the denouement, or the ‘marryin’ and buryin.’ The new status quo for the characters is established and, perhaps, explored. The newly established couples have a moment together, we mourn the characters who’ve died, the world has either returned to where it was in the opening, or the characters have entered a new phase of life.

I have cobbled these 9 points together from several different plot plans. None of this is really that original to me. But I don’t start drafting a book until I have these 9 points established. I can change things along the way, and often do, but if I have this firm of a plan, then I usually don’t write myself off a cliff the way I did before.

How this works for me is I plot out these nine points for each viewpoint character’s plotline. If I’ve done my job right, each plot thread has a different feel and a different set of stakes, but still fits within the whole. So, for my WIP where there are 5 different viewpoint characters, I did five plotlines and then braided them together into one outline. Yes, there were forty-five points on that plan. Still, while I know the big stuff, a lot of the scene by scene details I leave up to in-the-moment inspiration as for as how all of this develops and works out. Below is a picture of my plot board for the current WIP, with the plot points on post-it notes color coded by viewpoint character and plot thread.

So, that’s what I mean when I talk about being a plotter. This is what works for me, and it is a result of at least five years of iterating several different processes until I found something that clicked. I’ve written 12 books this way, and haven’t abandoned any books since I started doing this.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Across Genres: Blending Styles and Themes

When writers dare to venture into multiple genres within a single story, they open doors to creative freedom, unique storytelling experiences, and new ways to captivate readers. Writing across genres isn’t just about combining elements from two distinct categories, like romance and mystery, or science fiction and horror. It’s about weaving together themes, moods, and stylistic choices to form a…

View On WordPress

#Character Development#combining genres#creative writing tips#fantasy and sci-fi#genre blending#genre tropes#horror comedy#mixed genre writing#multi-genre stories#mystery and romance#Narrative Structure#novel writing#pacing in stories#Plot Structure#reader expectations#storytelling tips#Unique Storytelling#World-Building#writing a series#writing across genres#Writing Advice#Writing Inspiration#Writing Techniques#writing tone

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Structuring IF Side Plots

In a Choice of Games novel you must have multiple plots the player can pursue and that lead to a variety of end states based on the level of attention and success the player put toward that particular plot.

Central Plot

I am structuring my story with a central plot everyone plays through. The choices for this plot will focus on how they approach a task, why they're doing the task, and how they feel about the task. The choices will not focus on whether they do the task.

This central plot holds the story together, but also contains the least amount of player agency and so is also the least interesting plot available. Every single other plot though can connect to it through a character, a threat/stake, or other similar property.

Side Plots and my Struggle to Structure Them

These other plots are side plots. Each side plot should be engaging and something the player can care about. Each side plot should also have equal weight, which means I cannot hundreds of thousands of words on each. (Though I'm sure some writers do! There are CS games with more than a million words!)

Each side plot should also maximize player agency. One option would be to structure each plot as a series of questions or choices, but that did not work for me. I found I needed to know the what before I could put words to questions about it.

I explored narrative plot structures, but pinch points, second plot points, and so on rely on a high degree of authorial control. Players would rebel, I think, if you forced them to fail. Increased stakes or added danger? Yes. Required failure? No.

I looked up various blogs online to see what they said, but most focused on how to organize scenes into choice or dependency structures.

So I turned back to game mastering and writing up adventures for others to use. I read through adventures I'd written for Fate, Trinity Continuum, 7th Sea, and D&D--all very different systems. And, it was through doing that, that I landed on something that I think is going to work.

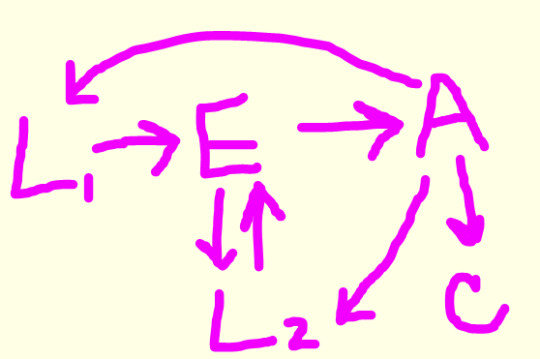

Learn - Explore - Act

Learn is when the player character (PC) becomes aware of the problem and the stakes. This is also an opportunity for the PC to reflect on the problem and to (re) commit to addressing it.

Choices in the Learn stage focus on how the PC feels about the situation and whether they want to (still) pursue it.

Explore is when the PC investigates or encounters the problem. (For example, the Thing was stolen! (Learn) Then, a man in a grimy cloak thrusts the Thing in the PC's hands and runs off (Explore-Encounter).)

Choices in the Explore phase focus on the PC's approach (e.g., how will the PC learn more), obstacles, and opportunities/useful diversions.

Act is when the PC must make a decision about what they've learned, gathered, and done. Acting leads to irrevocable change. It is the Point of No Return.

Choices in the Act phase focus on the PC's decision and completing the steps for carrying it out. These steps may involve choices related to approach, obstacles, and opportunities.

These are not strictly linear. The process is more like this:

(Description: A drawing of a system connecting letters with a series of one-directional arrows. L1 goes to E which either goes back and forth with L2 or to A. A goes to L1, L2, or C)

Note: In this case "C" is the conclusion and end of the plot. L1 is the hook for a new problem while L2 is the intensifying of the existing problem. A plot can contain more than one problem, depending on player actions.

As shown here, the Explore stage can lead to Act, but it can also lead to another Learn stage. The Learn stage, though, never leads to Act. While it may make sense to reflect on the problem and stakes before Acting, I think the tension is tighter if Exploration leads to a moment of Must Decide Now.

The Learn stage can lead to 'this is what I want to do,' but that triggers an Explore phase for pursuing that action and Explore continues until the Point of No Return.

The Act stage can lead to a conclusion, but may also lead to a new problem or the worsening of the current problem.

Why Is This (Potentially) Useful?

This structure helps me identify the anchor scenes. For each of my side plots, I know I need at least 1 Learn scene, 1 Explore scene, and 1 Act scene. Each of those scenes may contain multiple choices for the player to make.

I can even build an outline shell to fill in with details as I figure them out. For outlines, I like knowing the parameters of my map, but filling it in as I go. I think this will let me do that.

How does this work with Choice of Games?

This structure also maps onto the taxonomy of choices described by Choice of Games

Learn is primarily for flavor and establishing choices. The choices in this stage focus on the character more than their actions.

Explore may start with a forking choice, but is otherwise testing choices of all kinds, including objective testing choices (described in the next link).

Act is for the climax choice or, if too early for that, a forking choice.

Anyway! I'll try to remember to report back on how this does or doesn't work once I begin writing.

How have you identified key and anchor scenes for your stories? What processes and structures have you used?

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Preptober 2024 - Day 6

What would be the easiest way to write this story?

I actually have a structured plot this time with an ordered list of scenes sorted into three acts. AND I know the ending, unlike the last two times lol

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#neurodivergent#autism#audhd#adhd#women writers#creative writing#plot structure#neurodivergent writer#neurodiverse artist#writing tips#writing

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Writer's Workbook:

NOTE: I am not copying the book word for word. I am also adding my input and more advice.

Idea and Plot.

1.3: Key-Points.

Key-Points refer to the main outline of your story. While it is not necessarily a strict rule, it is useful to have some sort of structure that can be used to keep the reader interested and the pace of the book steady.

It can be simplified into the beginning, middle and end, or you can dive deeper into it using the 3-act story structure, but the main key-points of a story are:

Types of narrators are:

Exposition: Brief introduction to characters and setting. Should focus mainly on the main character and give a solid enough impression on them.

Inciting Incident: The point that drives the story into the main conflict. Hooks the reader onto the story.

Rising Action: The obstacles of the main conflict get more high-lighted. Growing tension.

Climax: Point of highest tension or the ultimate scene. Often fast paced and more challenging.

Falling Action: Conflict begins to resolve. How major is this point depends on how you plan to finish of the resolution.

Resolution: Just what it sounds like.

These plot points can be easily altered or made into more detail to fit your story, but the main structure is there. It can also change with different genres without much of a problem. You can always start the book with the conflict ongoing or end it with the issue finishing.

Plot twists are a key-point too in a way, in which the story-line takes an unpredictable turn. They increase the tension and stakes and once again can work in different stories or lack in some, but mainly, they are all about the execution.

Ask yourself:

Where does your story start and end?

What are the main things that happen at each point?

Main Post

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today we're looking at...

Okay, so, there are about as many plotting devices as there are writers out there. We all have different bits and pieces of advice that work for us and our stories, and since storytelling is inherently versatile, I'm afraid that this is a "no one method serves all" kinda deal. So... thanks for stopping by, catch you next time! 😘

HA, GOTCHA. Sit back down, please. There's a "however" coming.

However, most outlining practices come down to the same few plot beats that narratives must usually hit to keep the pacing tight, the characters developed, and the audience from pulling out the pitchforks.

One such method is 3 Act Structure. Yes, the very one you've already heard all about – it is widely popular, and for good reason! It's an effective way of arranging our fake little people doing their fake little stuff, but like, satisfyingly. It's through outlining that we make sure we didn't just ramble on for 400 pages, boring the reader to tears. A lot of times, when we think of a novel as being "badly written" (or, as I once saw someone describe The Metamorphosis by Kafka: "wtf"), we don't just mean that the prose itself was bad, but that the actual core of the narrative (what happens, in what way, and because of whose fuckery) was... well, wtf.

Now, believe it or not, I'm a corny soul with a bleeding heart, so I wanna help you be a little less lost in the tumultuous waters of the plotting sea. The waves of pacing and development do not need to wreck your boat, mate. To this end, I shall attempt to impress upon you the specific configuration of 3 Act Structure methods that I, Tumblr user jailforwriter – who is NOT an authority on any topic, making this post NOT legally binding – think works best.

Without further ado, we're looking at how each Act is subdivided into six subcategories, starting with Stage 1 of Act 1.

Act 1

Firstly, let's look at an overview of what needs to happen in roughly the first 25% of your novel. This section is all about introductions and setup: of the main players, the world, the stakes, the obstacles, and the themes. Chances are you're already clear about what'll happen in this section, because we humans are generally pretty good at beginnings and ends and pretty bad at everything in-between (see: The Roman Empire).

One thing to note here is that, while a lot of exposition will naturally happen at this stage, we must valiantly fend off the Frank Herbert-shaped demon on our shoulder telling us to take up three pages describing hyperspace travel. And it's not that we can never describe it – it's that it needs to be relevant and not detract from the tension, which exists in a fine balance between worldbuilding and action upset by the merest suggestion of power converters. But don't worry, I know that doesn't actually tell you much, which is why I'll go into further detail in another post, the sneaky devil that I am.

With that out of the way, let's delve a bit deeper and look at Stage 1.

Stage 1: Living My Truth

Well, not my truth. Your character's truth. Let's play a little game: reach for a novel right now and read the very first page, if you would. Unless it's a dream sequence or a flashforward/back or something wacky like that, chances are your protagonist is just hanging out in their world, doing their thing. This is called the Status Quo.

Oftentimes, the story will begin at a particularly crummy day for your protagonist, and they may or may not know why, and may or may not be aware that their life is about to go places. Bad places, for the most part, but places.

Let's look at an example. (*SPOILERS* for the beginning of the The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins).

In The Hunger Games, we open on Reaping Day, which sucks unfathomably for a lot of reasons. But Katniss knows about it, and that will affect the flow of information from her to us. What she does not know, however, is that her sister is about to be handpicked for a deathmatch, meaning that she doesn't know her life is about to change, which puts a crafty little asterisk in the way she's been conveying information to us so far and shakes everything up deliciously.

In this case, it's the author's job to get us up to speed on all the information relevant to understanding Katniss' situation without overwhelming us. Now, nothing exists in a vacuum, so it's worth noting that the audience will likely come with some preinstalled notion of what a dystopia is, so it's alright to leave certain details up to interpretation if it means not bombarding us with exposition.

Let's now look at a different example. (*SPOILERS* for the beginning of The Poppy War by R.F. Kuang).

In The Poppy War, the story opens with Rin having no clue that she's about to be sold off to be married, and the events from that point onward unfold as a direct result of her deciding that she ain't about that life, actually, and that she intends to do something about it.

In this case, we're as clueless as Rin walking into this situation, and while it's still the author's job to ensure we're not completely lost, there's a bit more leniency in how to go about it, since Rin is stumbling through the scene alongside us. She's learning the stakes, too, and the stakes suck so bad we instantly understand her urge to get the hell outta dodge.

Finally, if you permit, I'm afraid that I must be cringe and use an example from my own WIP, not because I think it's better than a published novel or really even close to it, but because my brain is fried from working on it and it's an easy-made example for what I want to discuss.

In The Paradox of Nonchoice, Nahia is well aware that she's about to walk into an exam, and that her future (and her family's, to an extent) depends on how well she performs in it. The focus of this scene is in getting across what the audience needs to know in terms of worldbuilding and stakes, which, in this case, are most important for understanding what's happening and why we should, y' know, care.

In this case, the tension is directly impacted by the protagonist's actions. The dynamic, along with the flow of information, is much more one-sided here, as there is no mystery being revealed to Nahia, or to us. In such instances – where we as authors control the narrative more closely – it's crucial that we ensure the stakes are clear and the consequences sucky.

Okay, so what can we get out of these examples, then? Well, for one, that there's a handful of things that Stage 1 of Act 1 needs to cover if we want things to flow naturally. Let's list them so we can refer back to these whenever we need:

Introduce the main character: the more, well, character that you can imprint upon the page in the first couple scenes, the better. The audience will be more likely to want to follow them if they find them interesting, or think that they stand out, somehow.

Introduce the world: and what's most immediately relevant for the audience to understand in order to follow along. We can reveal little morsels of worldbuilding throughout the rest of Act 1, so don't feel pressured to stick everything into Stage 1.

Background: some background details may be important for the audience to know as the first few scenes unfold and they get to know the characters and setting. For instance, it's okay to let us know that your protagonist hates makeovers if they're suddenly thrust into Queer Eye as their new mystery contestant.

Tone and atmosphere: this is crucial. The first few scenes should reflect the tone of the rest of the book (i.e. don't make the first scene hilarious if the rest of the novel is going to be an abject tragedy. The reader will feel scammed, I promise). Same goes for establishing atmosphere, with the caveat that you can sometimes play with it to subvert expectations or otherwise get a point across. I wouldn't recommend doing it right off the bat, though.

Themes: I cannot stress this enough: your themes will make your story! There is an absolute encyclopedia to be written about themes, and I will go into it with the fine-toothed comb it deserves in the future, but just know that your first scene needs to get across your themes. That's the core of your story! It matters!

Foreshadowing: listen, there's a reason they say you should write your first scene last. You need to be foreshadowing the events of the climax from the very beginning – this is part of the "setup" stuff we've discussed for Stage 1. Again, I'll be going into detail regarding foreshadowing as part of the Symbolism series, so please hang on tight if you're not sure how to go about it!

Finally, it's worth noting that there are cryptids who fly by with their galaxy brains and insane improv abilities as their only guide, having never once needed a word of plot structure advice yet still making it work, somehow. We'll delve into this "discovery writing" stuff later, to cover all our bases, but I just want to say, if you are a discovery writer reading this... how does it feel to know that you're God's favorite? Do you think She looks upon you with pride, and us disdain? Food for thought.

Anyway, that's it for now, thanks for sticking around for the long post!

Happy writing!

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Any other writers out there that want to take breaks from their wip but still want to be working towards their goals or thinking about how to improve their craft, this is my go to podcast to play while I get other tasks done. It's engaging, educational, and easy to digest.

#save the cat writing help#savannah gilbo#writerscommunity#writers on tumblr#writing#author#jessica brody#plot structure#books#book nerd#fiction writing made easy podcast

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ingrid Sundberg, Archplot Structure

#ordinary world#call to adventure#refusal of the call#crossing the first threshold#tests#allies#enemies#inmost cave#final push#seizing the sword#return#return with the elixir#archplot#plot structure#ingrid sundberg

5 notes

·

View notes