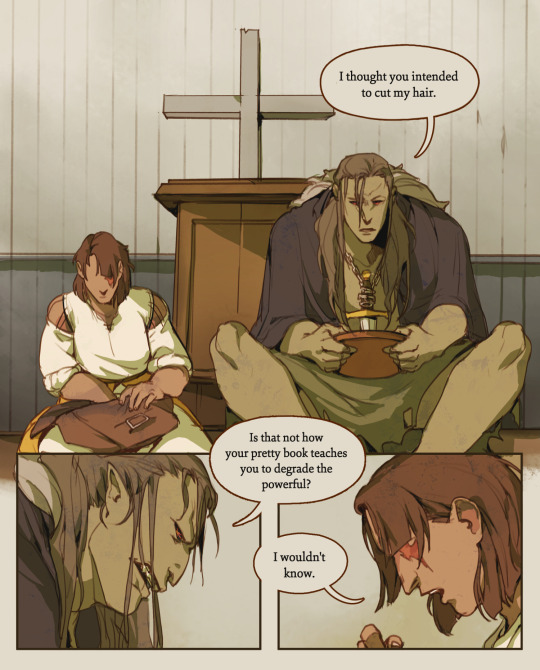

#as a theme. and not a particularly positive depiction either.

Text

seeing clearer

(sequel to another comic of mine, the calamity.)

--

all my other comics

store

#cw: eye scarring#cw: christianity#as a theme. and not a particularly positive depiction either.#the calamity has anger issues but is earnestly trying her best#the survivor is patient#and also not scared of her at all#the calamity is talking about the story of samson and delilah in pg 2 btw#i tend to only make oneshot short story these days but im fond of this pair#had the urge to draw something a little mundane with these two and the slowest slow burn of a relationship you could ever imagine#also usually a broken mirror would equal 7 years of bad luck but the calamity so outclasses it as far as bad omens go#im pretty sure the effects are just cancelled out#anyway#next comic will be a different story entirely i promise#thank you for your patience#and as always#thank you for reading#comic art#sapphic art#stillindigo art#hearteaters#stillindigo comics

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

I am not playing the “you're racist if you say Ed is abusive" game with y’all 😒

This shit is not new or helpful to POC in the fandom. I wrote about it earlier this year (too little, too late), so I've built this post up from that.

I encourage folks to read this analysis and call to action by uselessheretic from back in JANUARY since it addresses key aspects of the harassment campaign that was par of the course for the fandom in 2022. This discourse plays into that harassment.

Listen, for all of its widely-held progressive values, the ofmd fandom is still a hobby space filled with mostly white, first world, LGBTQ+ ppl. Most ofmd fans fashion themselves leftists and generally agree that structural racism exists and is a problem. Overall, there's worse fandoms to be in.

That said, this particular wave of hand-wringing about fans calling Ed abusive is not at all about the ways indigenous people are stereotyped in media.

The most telling giveaway is the timing: fans expressing frustration towards Ed following the sneak peek that shows Fang, Archie, Jim, and Frenchie all but having an intervention for Izzy because they think he is "in an unhealthy relationship with Blackbeard" since Ed "cut two more of his toes...[which] seems pretty toxic to me."

I am not emotionally prepared to deconstruct the dark humor of holding a spontaneous intervention for your asshole white assistant manager who's on his last fucking wit because your brown and beautiful rockstar boss is too high to function and keeps cutting the guy's toes off. You either get the joke or you don't.

For the purpose of this post, all I care to extract from it is what it tells us about who is exercising the most control over the ship. Despite his physical absence, Ed’s ghost is all over this beautifully crafted scene. The tone of their wardrobe is dictated by Ed’s. They are carrying out Ed’s orders. Frenchie and Jim’s exclusive presence as former members of Stede’s crew was decided by Ed. Izzy’s authority as first mate is sanctioned by Ed. And it is Ed’s fitness to lead that Frenchie, Fang, Jim,and Archie are questioning ultimately.

I’m not particularly worried about Ed’s integrity as a charismatic lead being hurt by a storyline that paints him as someone who abuses power--the flow and exchange of power is a running theme for ofmd. Stede and Izzy themselves abuse their power in season 1 for their vanity. What I am worried about is this cute cultural feature of the wider ofmd fandom:

the chronic unwillingness to grapple with interpersonal power dynamics amongst peers, not only in the show, but in the fandom itself.

So here we are again, ofmd fandom, working ourselves up into a moral outrage so that you, in your leftist white glory, can publicly police yourself because apparently you only know how to experience People of Color in fiction through these two lenses:

white guilt (am I racist for thinking this? are people around me racist for thinking this?) and

the white imagination (stories about characters of color are valuable because they inform my politics)

This push against reading Ed as abusive is not about calling out the problematics of depicting an indigenous man as mentally ill, violent, lonely, and rageful, it is about trying to sound self-righteous to mask anxiety about accidentally doing a racism on the indigenous, brown lead.

This is even more obvious now with the season 2 premiere days away and audiences being primed to question whether the severity of Izzy's punishment was appropriate.

Now, here's the hard-to-swallow pill the ofmd fandom's been avoiding cuz we don't wanna point out the inevitable problems of representation within canon:

We are being served a storyline where a complex protagonist (who happens to be a brown, queer, indigenous man in a position of power) harms people who are close to him and we are meant to recognize this as a problem that he must come to terms with. I don't like it either, but I'd rather have this than no Ed story at all.

Other people have written far more intelligently about this than I could, but it bears repeating: what's happening here is fans projecting their own insecurities about racism and power onto a white character ("izzy exotifies ed!" "he wants to control ed!" "izzy is an incompetent pirate actually!") while at the same time applying a shiny veneer of respectability and perfect rationality to a nonwhite character ("ed had every right to hurt izzy!" "maiming is fair game as retribution for racism, it's in-world rules!" "ed can't be abusive because he's been abused!") in order to mask white leftist fandom's discomfort about a morally ambiguous brown protagonist.

Anyway, take a breath.

Ed is a character whose impact in "the real world" does indeed go beyond how he makes us feel. Taika Waititi's Edward Teach represents a watershed moment in indigenous representation—not only for his position as protagonist, not even for his queerness, but because of his depth, charisma, complexity, and connection to a community that cares about him. These things have been rarely afforded to the very few indigenous leads in the global film canon--no matter how his story is handled in season 2 and 3, Ed's impact has already been cemented.

Okay I'm done, here's some actionable advice to wash this all down with.

If your goal is to foster a welcoming environment for fans of color and elevate engagement with characters of color, then immediately remove shaming people's headcanons from your toolbox and read this article. Take stock of who is in your fandom social circle and take stock of what you do in order to at least see more fanworks featuring characters of color.

If your goal is to promote or participate in productive race-conscious conversations with other fans, get real about your relationship with power, your positionality in life (and in fandom) and the channels through which you want to have these conversations. Some questions to start with: Can you describe your relationship with your race? What is your experience talking about race in mixed-race spaces? What avenues do you use to participate in fandom? How do you participate? Where do you have influence? How do you manage unwanted feelings that spark from disagreements about racism?

If your goal is to interact in fandom with integrity, get explicit about your values. Engage in dialogue, treat others with the respect you want. Be curious and ask questions. Avoid becoming someone's useful idiot and learn to think critically.

Finally, if your goal is to enjoy your blorbos without having to think about the problematics of representation for QTBIPOC (Queer, Trans, Black, Indigenous, People of Color), then save us all the grief and just join a different fandom.

Good luck!

#phew anyway#ofmd meta#cuz i actually had to explain the sneak peak scene oh my god#the izcourse#ofmd fandom#ofmd#our flag means death#fandom discourse#ofmd fandom discourse#fandom racism#long post#edward teach#ed teach meta#ofmd season 2#ofmd spoilers#ofmd fandom meta#thank u everyone who marinated on some of these thoughts with me in the circle <3 <3 <3 <3 <3 <3#and thank you everyone who proofread and gave feedback on this <3 <3 <3 <3 <3 <3#anyway ofmd fandom oh my god#please educate yourself#I hate to be like this but if you want to say meaningful shit about racism in this show#u need to do some actual fucking research and exercise your interpersonal skills lol#EDIT: fixed a couple links thanks anon!#la meta de mi meta

269 notes

·

View notes

Note

Yo!

What is a topic or theme you try to avoid in gt, either in your writing, your reading, or your perusing?

This is a solid question, especially because over the last year or so I've been finding myself exploring more topics/themes that I would have probably previously said I was not comfortable with. I'd like to genuinely thank @adjacentperception for being my partner in everything, including writing and creating, and for letting me have a sounding board and a space to feel safe while I dip my toes into some things I wouldn't have otherwise wanted to endeavour into on my own.

I guess in terms of like... things that disinterest me? If that makes sense? I'm not big on trying to explore family dynamics specifically through G/t. Sibling or Parent/Child relationships with size-difference mixed in just is something I tend to avoid while reading, and through writing I only ever explore it in the sense of like... 'this person is a good friend and is like a brother/sister to me', 'this person cares for me in a parental way sometimes'. Beyond that it's not something that catches my interest or tends to hold it for very long.

Anything that is too whump-heavy I tend to have a harder time reading, mostly because I just need comfort to go with my hurt. One of the projects I've got going on in the background now front-loads a bunch of the hurt before it starts getting to comfort, and I feel like-- especially the earlier chapters-- would qualify as whump. It's something that I could imagine myself having difficulty with reading on my own if I didn't know that it was going to pay off in comfort and (imo) satisfactory character growth for the mains, if only because I've been burned before on trying to struggle through something that was just... fucking miserable and it never got to a point where things got better/that comfort I desperately wanted came along.

Dislike vore/cannibalism to the extreme, anything remotely like that just squicks me out. A bit of mouthplay is fine in the sexy sense? Lips, tongue, maybe a bit of teeth? But there's a line that once it gets crossed I have to go detox with something after. I also can't do snuff at all. Just... too much. I'm not a gore/horror girl. It is not my cup of tea.

A topic I'll avoid depicting in any detail, and that I just get too depressed reading to really dive into very much, is long-term emotional/relationship-centered abuse, from either side. Particularly if a lesson is not learned by the offending/abusive party in a way that's satisfactory.

I'll dive into something like James Bond getting captured and tortured/interrogated by a villain for a hot minute, but a partner abusing a lover? Family being egregiously emotionally/psychologically abusive or neglectful for extended periods of time in the narrative? Someone in a care-taker position abusing a dependent? Too sad/enraging, won't do it, and especially as it pertains to G/t as an amplifier of that possible theming? Ow, no, my feelings. Faerie Spell comes the closest to that for me and that's still a stretch of what I'm actually comfortable with, as the neglect/abuse/disrespect is coming unintentionally and oftentimes against what the presumed goals of the characters perpetrating it actually are. It is still a dark place for my mind to go.

Other than that, I can't think of much that I would say is a definite no-go for me? How something is written/handled within a narrative can be a big factor in whether or not I stick with reading something, typically, and I'm willing to stretch my comfort a bit in some areas if the rest of the story is making up for any discomfort/loss of interest I wind up feeling because of any given element.

Thank you so much for the ask!

#asks and answers#g/t#giant/tiny#giant tiny#g/t writing#g/t author#gtauthor#author thoughts#gt#big little thoughts

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Review: Seed of Chucky (2004)

Seed of Chucky (2004)

Rated R for strong horror violence/gore, sexual content and language

<Originally posted at https://kevinsreviewcatalogue.blogspot.com/2023/07/review-seed-of-chucky-2004.html>

Score: 2 out of 5

Seed of Chucky is, without a doubt, the most overtly comedic entry in the Child's Play franchise, specifically serving as writer and now director Don Mancini's take on a John Waters movie, right down to casting Waters himself as a sleazy paparazzo. It's a film full of one-liners, broad gags, gory kills that are often played as the punchlines to jokes, and most importantly, sexual humor, particularly in its depiction of its non-binary main character that is admittedly of its time in some ways but also a lot more well-intentioned than its peers, and holds up better than you might think for a movie made in 2004. This was really the point where Mancini being an openly gay man was no longer merely incidental to the series, but started to directly inform its central themes. In a movie as violent and mean-spirited as a slasher movie about killer dolls, this was the one thing it needed to handle tastefully, and it more or less pulled it off, elevating the film in such a manner that, for all its other faults, I couldn't bring myself to really dislike it.

Unfortunately, it's also a movie that I wished I liked more than I did. It's better than Child's Play 3, I'll give it that, but it's also a movie where you can tell that Mancini, who until this point had only written the films, was a first-time director who was still green around the ears in that position, and that he was far more interested in the doll characters than the human ones. The jokes tend to be hit-or-miss and rely too much on either shock value or self-aware meta humor, its satire of Hollywood was incredibly shallow and made me nostalgic for Scream 3, and most of the human cast was completely forgettable and one-note. Everything connected to the dolls, from the animatronic work to the voice acting to the kills, was top-notch, but they were islands of goodness surrounded by a painfully mediocre horror-comedy.

Set six years after Bride of Chucky, our protagonist is a doll named... well, they go by both "Glen" and "Glenda" (a shout-out to an Ed Wood camp classic) throughout the film and variously use male and female pronouns. I'm gonna go ahead and go with "Glen" and "they/them", since a big part of their arc concerns them figuring out their gender identity, and just as I've used gender-neutral pronouns in past reviews for situations where a character's gender identity is a twist (for instance, in movies where the villain's identity isn't revealed until the end), so too will I use them here. Anyway, we start the film with an English comedian using Glen as part of an "edgy" ventriloquist routine, fully aware that they're actually a living doll and abusing them backstage. When Glen, who knows nothing about where they came from except that they're Japanese (or at least have "Made in Japan" stamped on their wrist), sees a sneak preview on TV for the new horror film Chucky Goes Psycho, based on an urban legend surrounding a pair of dolls that was found around the scene of multiple murders, they think that Chucky and Tiffany are their parents, run off from their abusive owner, and hop on a flight to Hollywood to meet them. There, Glen discovers the Chucky and Tiffany animatronics used in the film and, by reading from the mysterious amulet they've always carried around, imbues the souls of Charles Lee Ray and Tiffany Valentine into them. Brought back to life, Chucky and Tiffany seek to claim human bodies, with Tiffany setting her eyes on the real Jennifer Tilly, who's starring in Chucky Goes Psycho, and Chucky setting his on the musician and aspiring filmmaker Redman, who's making a Biblical epic that Tilly wants the lead role in.

More than any prior film in the series, this is one in which the human characters are almost entirely peripheral. Chucky and Tiffany are credited as themselves on the poster, the latter above the actress who voices her, and they get the most screen time and development out of anybody by far, a job that Brad Dourif and Jennifer Tilly proved before that they can do and which they pull off once again here. Specifically, their plot, in addition to the usual quest to become human by transferring their souls into others' bodies, concerns their attempts to mold Glen/Glenda in their respective images. Chucky wants them to be his son, specifically one who's as ruthless a killer as he is, while Tiffany, who's trying not to kill anyone anymore (even if she... occasionally relapses), hopes to make them her perfect daughter. Their arguments over their child's gender identity are a proxy for the divide between them overall as people, building on a thread from Bride of Chucky implying that maybe theirs wasn't the true love it seemed at first glance but a toxic relationship that was never going to end well, especially since they never bothered to ask Glen what they thought about the matter. Glen is the closest thing the film has to a real hero, somebody who doesn't fit into the binary boxes that Chucky and Tiffany, both deeply flawed individuals in their own right, try to force them into, and series newcomer Billy Boyd did a great job keeping up with both Dourif and Tilly at conveying a very unusual character. Whenever the dolls are on screen, the film is on fire.

I found myself wishing the film could've just been entirely about them, because when it came to the humans, it absolutely dragged. As good as Tilly was as the voice of Tiffany, her live-action self here feels far more one-dimensional. We're told that she's a diva who mistreats her staff and sleeps with directors for parts, but this only comes through on screen in a few moments, as otherwise Tilly plays "Jennifer Tilly" as just too ditzy to come off as a real asshole. As for Redman, it's clear that he is not an actor by trade outside of making cameo appearances, as he absolutely flounders when he's asked to actually carry scenes as a sleazy filmmaker parody of himself. Supporting characters like Jennifer's beleaguered assistant Joan and her chauffeur Stan are completely wasted, there simply to pad the body count even when it's indicated (in Joan's case especially) that they were shaping up to be more important characters. There was barely any actual horror, to the point that it detracted from the dolls' menace. The satire of showbiz mostly amounts to cheap jabs at Julia Roberts, Britney Spears, and the casting couch, and barely connects to the main plot with the dolls, even though there was a wealth of ideas the filmmakers could've drawn on connecting Glen's quest to figure out their identity with the manner in which sexual minorities and other societal outcasts have historically gravitated to the arts. This was a movie that could've taken place anywhere, with any set of main human characters, and it wouldn't have changed a single important thing about it, such was how they faded into the background. At least the kills were fun, creative, and bloody, including everything from razor-wire decapitations to people's faces getting melted off with both acid and fire, and the fact that I didn't care about the characters made it easier to just appreciate the special effects work and the quality of the doll animatronics.

The Bottom Line

Seed of Chucky is half of a good movie and half of a very forgettable one, and one that I can only recommend to diehard Chucky fans and fans of queer horror, in both cases for the stuff involving the dolls. It's not the worst Chucky movie, but it's not particularly good either.

#seed of chucky#chucky#2004#2004 movies#horror#horror comedy#comedy#horror movies#comedy movies#slasher#slasher movies#supernatural horror#queer horror#brad dourif#jennifer tilly#billy boyd#hannah spearritt#don mancini#john waters#redman

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

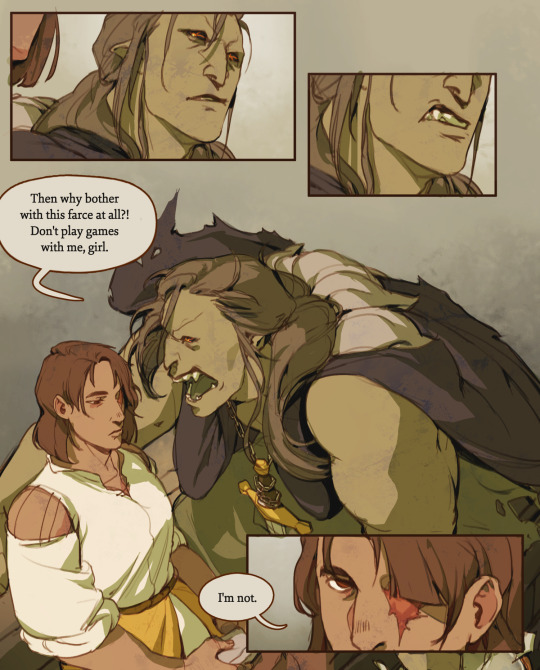

Raybearer, by Jordan Ifueko

⭐⭐⭐⭐ 1/2

Tarisai has been raised from birth to excel, to rise above all others from her land to attain a coveted position on the Council of Eleven, and then to kill the crown prince. Bound by the circumstances of her birth to obey her mother's command, Tarisai is desperate to find a way to protect the prince she's come to love from the hidden threat that she herself poses. Will she be able to defy the destiny her mother has chosen for her?

I loved the worldbuilding here, particularly the depictions of the lands we got to visit and the themes of embracing unique cultures vs assimilation. There's a darker edge to many of the systems in this world, which I also appreciated. While the protagonist was rather unquestioning of some things that should have thrown red flags(basically everything about the council), this is only the first book of a duology, so those aspects might be examined later.

The central conflict is, of course, Tarisai's struggle to break free of her mother's command. I initially got some Ella Enchanted vibes from this setup, but the resolution wound up being so much more. It wasn't enough for her to merely want to disobey, or even to desire to protect the prince with her whole heart; to break a curse of this magnitude, it would take much more than that. I also appreciated how her mother was handled in the narrative. She wasn't purely evil, but she wasn't misunderstood either; she was a complicated, wounded character who committed great harms.

Overall, I enjoyed this a lot more than I'd expected to. It helped that the romance was firmly a subplot, and there was no love triangle. I'll say that again for those in the back: this YA title has no love triangle! It was so refreshing to see a depiction of platonic love develop between two characters. There was even a prominent character who was explicitly asexual. As mentioned, this is the first book in a duology, and I intend to pick up the sequel, Redemptor, whenever I manage to find a gap in my TBR(lol).

#books#book review#raybearer#jordan ifueko#ya fantasy#fantasy#afrofantasy#young adult#ya fiction#botb 2023

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

I get your recent post but struggling with accepting that there was anything good (like friendship or love) that came out of the war is also very much a theme in mash, especially in gfa

Yeah so in the longer, less coherent version of that post in my head, I also talk about how MASH undermines its own message by staying on for eleven years. And like, it's okay. I'm okay with it. But I think if you look at the original core message of MASH at the beginning, the idea of good coming out of the war is not there. I mean, in The Interview, Potter, one of the career military characters, is asked if he sees any good coming out of the war and says "not a damn thing." I think the cast's feelings as well as the audience's feelings are necessarily projected onto the characters after that long, and we're just attached to them and see their friendships as good, because our circumstance is watching them on TV. Not, you know, actually being in a war.

But even so, I think if you asked Hawkeye if he'd trade the friendships he made during the war to make it so the war never happened, he would not hesitate to say yes. Of course, you can't say yes, that's a dumb hypothetical, so what you get back to is these relationships that formed under horrible circumstances because that's life. But GFA still shows them all going their separate ways as the happy ending. I think it's notable that MASH doesn't have Hawkeye particularly grow as result of the war. His morality is in place from the beginning. Sidney tells him maybe his own pain will help him understand his patients better, but that's it.

One of the things that all depictions of war struggle with, including openly anti-war ones like MASH, is not showing it as good. If you want to show an individual character's development and you show them succeeding in life after the war, someone in your audience is going to decide it's because of the war. MASH does get into this somewhat and while I don't blame the show for it or necessarily think it's avoidable, I do think it's important to be aware. Some people do become better people as the result of traumatic events, but you don't want to say those events are broadly worth it. Charles pretty clearly becomes a better person when he's confronted with real suffering and forced to empathize with people unlike him. But Charles was kind of a bad person to begin with. Margaret is similar; she's spent her entire life in the army and believing in it, and maybe the war gives her a different perspective. But she wasn't a great person in the beginning, either. Neither of those, in my opinion, is comparable to a narrative of discovering one's true self.

My issue is, fanfiction, especially if its romance, usually takes a love conquers all stance whether it means to or not. If your fic is about a man realizing he's gay while serving in the Korean War and understanding his sexuality is ultimately a positive development in his life, you are, whether you mean to or not, sending the message that the war was a good thing. A good thing for him, but when the story is about him, that means a good thing. Particularly when the focus is on the queer journey or love story, because the bulk of what the audience sees is then the good thing that came out of the war. I don't think that's comparable to GFA, which focuses quite a lot on the destruction.

And I don't think most fic writers looking for queer wish fulfillment particularly explore the nuances of feeling grateful for the effect an objectively horrific event had on the main character's personal life. And I'm not taking a moral position on whether they should or not, it's simply that I want nothing to do with those stories.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I need a palate cleanser.

From a more positive position, I think putting forth a thesis for why sex and eroticism in fiction can be meaningful - not as a refutation to sexual violence, but purely on its own terms - is actually worthwhile. Because there should be a positive model to the acceptable depiction of 'sex' as rape, and that informing the archetypal dynamics of sexuality in storytelling. It's not like the model should be rape or nothing, objectification or nothing. People think you're trying to take away the only expression of their sexuality that they've got in this sort of topic, and I find it very weird, particularly in feminist spaces and the proshipping debate.

Again, my stance on proshipping/anti shit is that it's schoolyard bullying and moral nuance goes there to die. But on the other hand in my experience it's not like either side really tends to value positive expression of sexuality - it's only about exploring the most taboo (rape) and the other side trying to spin everything as rape because all sex and explicit content is bad. It's fucking bananas. I get that proshippers have their reasons for writing the really dark stuff but when it's done for barren textual purposes I just don't see the justification. Sure, I am not disputing AO3's policy, I just wonder whether it is always artistically defensible. Because that's basically my metric.

But I'm more interested in what eroticism offers storytelling. I think that there is plenty of dark stuff that has genuinely justified ideas - and I think that exploring violence and darker dynamics is not in itself unjustified and is in fact found uncritically in a lot of published literature - but the usual refutation is that I'm trying to police peoples' creative expression, especially in fannish spaces where don't like, don't read. But if I'm trying to find a personally valuable model for sexuality in storytelling, and I'm trying to identify my discomfort, and I'm trying to identify why I'm okay with some of it (I read a Gothic horror romance done very well once in fanficland) and some of it I'm not, then I actually want to consider how it lines up with my own personal conception of what sex (and darker themes related to that, even) achieves in storytelling. Clearly there is something workable here which doesn't play into anti schoolyard bullshit that isn't also thought-terminating 'but I enjoy it' type annoying refrain - which if I categorically reject as cultural criticism and as something which defends, say, the unrealistic, fetishistic depiction of rape, I don't see how I can entertain it in fanfic.

I don't have a personal issue with proshippers the way I do antis, and as I've said I nominally agree with that position. But I don't think it should be a conversation-ender.

As I gestured at, though, it's interesting that even the proshipping debate largely revolves around the taboo - rape, incest, so on and so forth - and not the expression of positive sexuality itself. I feel alienated in that sense, I suppose, but I also think from a position of argumentation - the antis are swift to decry sexuality, so why is it that we conceive of sexuality in proshipping circles as interchangeable with sexual violence?

1 note

·

View note

Text

fight club, fathers, franchises and ideal selves: a commentary on the absentee american dream

the first rule of fight club is to build a family according to a business model. the second rule of fight club is to blame your father.

brotherhood to fellowship to a hierarchy of space monkeys; this is the progression of antagonist tyler durden’s ‘project mayhem’ in chuck palahnuik’s 1996 book, ‘fight club.’ the anticapitalist cult classic of the late 90s entered the mainstream years after the release of david fincher’s 1999 movie adaptation. the book depicts late stage american capitalism and specifically a masculine reaction to it – the protagonist grows to resent his ‘lovely nest’ of belongings, realising he has very little identity outside of the ikea home he’s built for himself, and begins to spiral into a schizophrenic episode resulting in the destruction of his local, and eventually national economic structures. palahnuik’s ‘stream of consciousness’ style of writing gives us an insight to his unnamed narrator’s psychological decline, providing commentary not just on the events at work in the novel, but commentary of the wider context of american consumerism and men’s roles in it.

linking men’s identities with corporate positions even outside of work environments is a vital theme of the story that palahnuik establishes early on. this characterises the relationships between men as having a business-like aspect to it, as though they are mostly transactional. this is particularly applied to familial relationships, both within the text and within palahnuik’s own philosophies, and is attributed to american culture and attitudes. our narrator describes his absentee father’s patterns as very detached: ‘my dad, he starts a new family in a new town about every six years. this isn’t so much like a family as its like he sets up a franchise.’ this stems from the idea that instead of a person, you exist as product or a branding, or a company. fathers are often likened to high authorities in this text: ‘if youre male and youre christian and living in america, your father is your model for god. and if you never know your father, if your father bails out or dies or is never at home, what do you believe about god?’…‘how tyler saw it was that getting god’s attention for being bad was better than getting no attention at all. maybe because gods hate is better than his indifference.’ the connotations of ‘god’ in this excerpt grant the role of father a tremendous amount of influence, but also a kind of mythical element to it. in the context of corporate roles, this volume of power would put fathers at the top of the hierarchy, like ceos or company founders. actual ceos, or work bosses, serve as ‘secondary fathers.’ palahnuik explains this concept by referring to joseph cambell: ‘[joseph campbell] said that beyond a person’s biological father, people needed a secondary father — especially men. typically that was a teacher, coach, military officer or priest. but it would be someone who isn’t the biological father but would take the adolescent and coach him into manhood from that point. the problem is that so many of these secondary fathers are being brought down in recent history. sports coaches have become stigmatized. priests have become pariahs. for whatever reason, men are leaving teaching. and so, many of these secondary fathers are disappearing altogether. when that happens, what are we left with? are these children or young men ever going to grow up?’

fight club’s narrator introduces his job as something that he is disillusioned with. his insomnia combines the formulaic nature of his job and frequent travelling make it pass in a mindless blur. taking campbell’s theory into consideration here, it can be assumed that is ‘secondary father’, in this instance his boss, has failed him. readers later discover that his biological father, who creates new families like ‘[setting] up a franchise’, did not guide him either: ‘after college, i called him long distance and said, now what? my dad didn’t know. i got a job and turned 25, long distance, i said, now what? my dad didn’t know…i’m a thirty-year old boy.’ the narrator, sometimes referred to as readers as ‘jack’ or ‘joe’, presents himself as a relatively average representation of his demographic. this suggests that in answer to campbell’s question, ‘are these children or young men ever going to grow up?’, the narrator’s experience can be generalised. he often explains his emotions through a format found in old health magazines: ‘in the oldest magazines, there’s a series of articles where organs in the human body talk about themselves in the first person: i am jane’s uterus.’ ‘i am joe’s inflamed sense of rejection…i am joe’s wasted life.’ in fincher’s movie this is changed to ‘jack’, but the connotation of ‘average joe’ remains the same. in remaining unnamed, the narrator is an everyman, a broad reflection of masculine american culture that a readers of that demographic can relate to. in reaction to feeling like an adult child, tyler (and by extension the narrator, hereby referred to as joe) gradually work up from fight club to project mayhem, an all-male organised crime unit that functions similar to an army. while there are more details to project mayhem’s structure, it operates under a systemic hierarchy similar to that of a corporation, with departments and bosses. the core difference is that the ‘employees’ are not paid, and the unit operates not just outside of but against society, the headquarters beyond the edge of town, the members antagonising the public and authorities. initially the idea that tyler and joe have mirrored the corporations they aim to destroy seems ironic, but it does serve the pair a purpose. by founding this corporation-like project themselves, tyler and joe create founder or ceo roles for themselves. this places them at the top of the hierarchy, allowing them to experience the power of the men who failed them (namely bosses and absent fathers). project mayhem seems to naturally take on this structure, despite being separate from american society. implicit in this is the suggestion that power structures are not just ingrained in american capitalism, but in modern masculinity. the masculine response to controlling powers in this text was to take over the controlling powers yourself; while project mayhem’s aim is framed as dismantling regional, and eventually national, capitalistic authorities, it transpires that tyler and joe shift this power to themselves, even if it is only within the context of this obscure group and its branches in other states.

palahnuik, in response to the suggestion that fight club is a gendered text, states that ‘it was more about the terror that you were going to live or die without understanding anything important about yourself. in the book it does directly criticise capitalism’s impact on everyone: you have a class of young strong men and women, and they want to give their lives to something. advertising has these people chasing cars and clothes they don’t need. generations have been working in jobs they hate, just so they can buy what they don’t really need.’ this sentiment is abundantly clear in the text, both thematically and in some chapters, said explicitly. fight club is renowned for its anti-consumerist rhetoric, however its predominantly male cast of characters, and overt comments specifically on the relationship between american consumerism and masculinity does make the book a gendered working critique of capitalism. pahalnuik rarely addresses feminine responses to advertising and corporate employment, and it is certainly not central to the narrative in the way that masculinity is. the author’s other works, namely adjustment day (2018) follows a similar theme. it depicts an armed insurrection that overturns american society. this insurrection is triggered by a corrupt senator’s plans to draft young men, with the intention of letting them die in a planned nuclear attack in the middle east, preventing those same men from staging an uprising. these american men, upon discovering the plot, rise up and kill figures the public have voted online as most deserving to die before the vote to reinstate the draft, and become the united states’ new leaders. this echoes sentiments from fight club, particularly those surrounding the suppression of young men, and the idea of taking power for yourself rather than dismantling power structures altogether. whether intentionally or not, palahnuik focuses on a gendered reaction to american society, with his discussions targeting the culture’s obsessions with consumerism and war.

while the military and advertising culture are staples of the united states, these are not entirely at the frontline of the ‘american dream.’ in fight club 2, the narrator is seemingly living the american dream, characterised by white picket fences, a wife, a child, and so on. despite outwardly living a life sought after by many, joe remains unfulfilled. palahnuik describes this by musing, ‘it’s funny, it isn’t the process of getting stuff, it’s the stuff itself that becomes the anchor. it’s ‘buy the house, buy the car’ and then what? it’s that isolated stasis that’s the unfulfilling part you ultimately have to destroy. that’s the american pattern — you achieve a success that allows you isolation. then you do something subconsciously to destroy the circumstance because you can come down into community after that.’ this mimics motifs from the original fight club, in which the narrator discusses ‘[wanting] to destroy something beautiful’ as a form of catharsis. ‘i wanted to destroy everything beautiful id never have…i wanted the whole world to hit bottom.’ interestingly, a piece of media that conveys a similar point of view on the american dream is the song ‘once in a lifetime’ by the talking heads. it’s argued that the disconnection david byrne describes is reflective of an autistic view on the world. however it does echo the lack of fulfilment the advertised ‘american dream’ can provide. byrne sings, ‘and you may find yourself behind the wheel of a large automobile / and you may find yourself in a beautiful house, with a beautiful wife / and you may ask yourself, ‘well how did i get here?’ the song is punctuated by a chorus that repeats the line ‘letting the days go by, let the water hold me down.’ the drowning motif used here is often used in conjunction with feelings of unfulfillment or dissatisfaction, as is reflected in fight club 2 and other similar media. at the start of fight club the narrator feels the same way, insomnia blurring his job and ikea home and work commutes into one dissatisfying experience: ‘this is your life, and its ending one minute at a time…you wake up, and you’re nowhere.’ the destruction of something outwardly desirable, such as blowing up joe’s perfectly curated and furnished apartment, breaks him free of this.

tyler is almost drawn as the antithesis to joe to begin with. there is one key device that demonstrates this; marla singer. it is, of course, incredibly reductive to refer to a female character as a ‘device’, and marla exists to add more to the plot than just illustrating the narrator and tyler’s relationships. however, the distinction between how marla receives joe and how marla receives tyler is significant in charactersing the two of them. for the narrator, marla initially acts as a mirror: ‘her lie reflected my lie…to marla i’m a fake.’ upon meeting marla, the narrator immediately dislikes her because her dishonestly disrupts the benefits he gets from his own dishonesty. they both use these support groups to invoke more feeling in their otherwise dull or flattened experiences; palahnuik describes this by stating that ‘in fight club the [support] groups showed up to create life by being present to death, imminent death.’ for joe, being surrounded by hopelessness, ‘rock bottom’ allows him the emotional release that tires him out enough to cheat insomnia. for marla, the groups are a continuation of her fascination with death, a step up from working at funeral homes; ‘‘funerals are nothing compared to this,’ marla says. ‘funerals are all abstract ceremony. here, you have a real experience of death.’’ ‘she actually felt alive…all her life[…]there was no sense of life because she had nothing to contrast it with.’ in contrast, marla’s relevance to tyler seems predominantly sexual, and the early stages of their relationship are described bluntly and graphically: ‘one morning, there’s the dead jellyfish of a used condom floating in the toilet. this is how tyler meets marla.’ marla’s insistence on speaking with joe seems nonsensical to him, as he was not mentally present during his sexual encounters with her, and tyler’s insistence that joe not tell marla about him draws a sharp contrast between each personality’s relationship to her. ‘ok. you fuck me, then snub me. you love me, you hate me. you show me a sensitive side, then you turn into a total asshole. is this a pretty accurate description of our relationship?’

marla arguably becomes the middle man for highlighting any homoeroticism between joe and tyler, illustrated by joe’s jealousy. joe is not jealous of tyler for having relations with marla, but the other way around. he asks, ‘how could i compete for tyler’s attention. i am joe’s enraged, inflamed sense of rejection.’ towards the movie’s end, upon the reveal that tyler and joe are one person, tyler says ‘all the ways you wish you could be? that’s me.’ this indicates that the jealousy was more centred around his own insecurity, but joe desires tyler’s attention specifically, alluding to a relationship between them. this obviously becomes somewhat dangerous territory here as the pair are technically one person, so a relationship between them would be somewhat incestuous but even in one body they seem like two entirely separate people, if not just in terms of physical appearance. in fincher’s movie adaptation, tyler (brad pitt) and joe (edward norton) share bottles and cigarettes with one another after fighting, fincher’s subtle way of painting physical violence as potentially sexual or intimate. this is illustrated in this moment from the film’s commentary that occurs after the initial fight between the pair: [tyler takes a sip from the bottle] fincher: i love the post-coital smoke. pitt: it’s touching.

the relationship between a man, in this case joe, and his ideal self, tyler, has this intense charge which can obviously be mistaken to be sexual; it is arguably more in tune with the narrative to consider that this intensity is centred around ideas of control. joe is intended to represent that average american man, suggesting that palahnuik is using him as a vehicle to discuss the feeling of incongruence in men in this era. humanist psychologist describes incongruence as ‘unpleasant feelings…result[ing] from a discrepancy between our perceived and ideal self.’ essentially, the root of joe’s boredom and distress can be found in the differences between him and tyler. the tense bond between them lies in the struggle for control; the novel personifies the ideal self and depicts a hypothetical scenario in which this ideal self seizes the autonomy of the individual in order to achieve congruence (an overlap between the perceived and ideal self). congruence is the aim of humanistic psychotherapies. by helping an individual feel less distant from their goals and aspirations as a person one can be more content in themselves. what tyler does in this novel is an extreme reaction to the feeling of incongruence. his reaction encourages the men around him, in both fight club and project mayhem, to change their ideal self from the men they see in adverts to something less ‘self-indulgent’ and take control of their lives to achieve it. ‘we’ve all been raised on television to believe that one day we’d all be millionaires, and movie gods, and rock stars. but we won’t. we’re slowly learning that fact…you are not special! you are not a beautiful or unique snowflake!...it’s only after we’ve lost everything that we’re free to do anything.’ in taking these men out of the public sphere and creating an entirely new environment separate from capitalistic society, each member’s ideal self becomes less influenced by advertising, television, and so on, and they are given the space to achieve congruence without societal obstacles such as jobs and families. when taken outside of regular society, these influences begin to have less effect on our identity: ‘you are not your job.’ however, project mayhem still functions similar to an army division or a cult, with its own specific hierarchy designed to suit tyler’s agenda. the congruence between tyler and joe is prioritised over all else given the intense battle over which of them is able to control the body; their combined attempt to maintain their ideal self in some way or another is the most visceral of all the characters, and is the main trigger for the events of the text.

fight club, as a piece of text, essentially functions as social commentary, through the lens of one ‘everyman’s’ neurochemical drama. joe’s struggles are specific to his role in society and his interactions with consumerism, which are depicted in a way that makes them applicable to much of his demographic: in this case, white men in 1990s america. palahnuik creates a narrative that forces the narrator to experience a push and pull effect between his real situations and ideal ones, to the point of creating something entirely separate. his experiences serve as a clear critique of capitalism and its inverse relationship to masculinity. the narrator’s identity warps and changes depending on his roles within, or distance from, consumerist structures. palahnuik’s motif of experiencing events the way one does an aeroplane ride continues throughout joe’s narration, emulating the switches from boredom to terror to acceptance that one experiences in such a structure: ‘we have just lost cabin pressure.’ the participants of fight club represent the usa’s disillusioned youth, their attitude to their jobs, their anger, and their failing desire to participate in capitalism any further. ‘may i never be complete. may i never be content. may i never be perfect.’

i.k.b

#fight club#fight club analysis#literary analysis#movie analysis#film analysis#critical essay#long post#fight club movie#fight club book#chuck palahniuk#david fincher#textpost#analytical essay#books and literature#90s films#film#favourite movies#movies and tv#cult classic#cult film#capitalism#consumerism#masculinity#anti capitalism#anticapitalist lit#tyler durden#marla singer#brad pitt#edward norton#helena bonham carter

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

Asteroids Part 6; Sisterhood of Pallas Athena, Symbolism of the Asteroid Pallas Athene

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5

The long overdue sixth part of my asteroid series is finally here.

The asteroid Pallas Athene is one of the more prominent asteroids covered in the astrological community thanks to Demetra George’s “Asteroids Goddesses; The Mythology, Psychology, and Astrology of the Re-emerging Feminine.” In this part, I will cover the asteroid’s symbolism and interpretation based on mythology, gathered research from authors such as Demetra George, and my own knowledge.

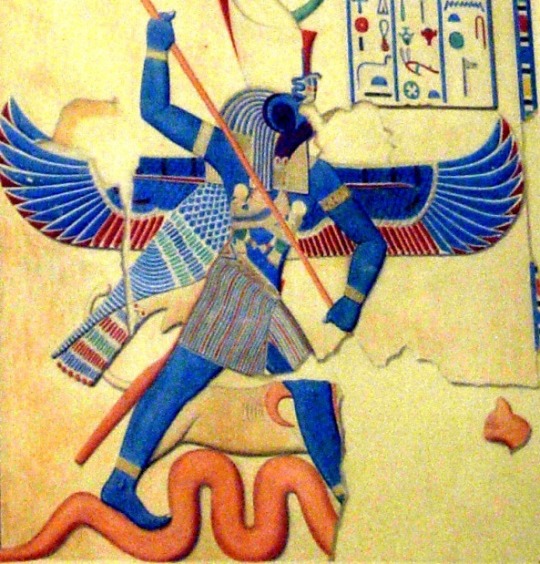

The ancient Greek goddess Athena may have been synonymous with the Egyptian goddess Neith and possibly other earlier known goddesses. Throughout this asteroid series ( and just in general for my astrological interpretations) I’ve tried to peel back further from Greek origins and more toward Kemetic or Sumerian origins for a pure and truly ancient understanding of asteroids named after Greek deities. However, I’ve accepted that for Pallas Athene, the Greek mythologies derive important symbolism that just isn’t clearly depicted from what we know of Neith or other earlier goddesses synonymous with Athena.

The Mythologies of Athena

Athena is the goddess of war and wisdom. She was revered by gods alike and those who worshipped her for her remarkable strength, courage, wit, and creativity. Her birth story begins with Zeus swallowing the titan Metis who was carrying the unborn Athena. After some time had passed, Zeus develops a headache that would only be cured by Hephaestus’ splitting open his skull. Out from Zeus’ skull Athena is born as a fully grown woman encompassing all of her remarkable traits. Athena was Zeus’ favourite child, for she was his creation; so purely in his image of goodness, power, and wisdom.

Like Vesta (or Hestia), she is a virgin goddess, she serves herself and is whole with herself. Though, she had a friend who she quite possibly could have been in love with and she did love; Pallas.

Athena and Pallas

Pallas was the daughter of Triton. She was equal to Athena in wisdom and the art of war. They were partners in battle and one day the gods were disputing which of the two goddesses were stronger. So the two goddesses sparred and Zeus interfered allowing Athena to have the upperhand. Unfortunately this ended up fatally wounding Pallas. Athena was so heartbroken that she added Pallas’ name to her own to honour her. While it is never mentioned in the myth between these two goddesses, I speculate the possibility that their relationship may have been more, possibly as lovers in war. In ancient Greek and Roman times, it was a known practice that soldiers would often become romantically involved with one of their peers, even if they had a partner back at home. This was because they believed you would fight better for someone you love, especially if it was to avenge the death of a lover.

Athena and Medusa

While there are several interpretations of this particular myth, the one that I find significance with is the one that describes Athena aiding Medusa.

Medusa was said to once be a very beautiful woman who made a vow for herself to remain virginal. However, her beauty drew on the male gaze and she was preyed upon against her will. The ocean god Poseidon tried to have his way with Medusa, but Athena stepped in and transformed Medusa into an ugly creature with snakes for a head of hair, and anyone who looked into Medusa’s eyes would turn stone.

This myth often depicts Athena as jealous of Medusa’s beauty, but in truth, this would be extremely out of character for Athena who’s not concerned with how others perceive her, particularly men. Athena cloaks Medusa with ugliness as a defense– as a way to protect Medusa from unwanted attention. This myth parallels greatly with the internal struggle many people have, particularly women, with the threats and vulnerability that coincide with embracing beauty and femininity.

Helper to Heroes

Athena often makes appearances in myths about a hero’s journey and aids the hero in some way. She often has some sort of valuable foresight or tool to give the hero. Mortals look to her for her strength, wit, and strategy.

The story with Medusa continues as Athena actually aids Perseus upon hearing he needs to take Medusa’s head. She gives him a reflective shield so he can see Medusa without looking into her eyes and turning to stone. Many of the common interpretations of this myth state that Athena hated Medusa which is why she was so willing to help Perseus on this quest. However, following the interpretation I mentioned where Athena turned Medusa into a gorgon for her protection, Athena would have been the only one to understand the circumstances of Medusa. In addition to this, in the myth itself Medusa plays more-so as a symbolic prop instead of a character. Particularly because Medusa as a gorgon is described as having snakes for hair– snakes in myths can (but not exclusively) symbolize treachery and bad spirits needing to be expelled. We see this in stories like Inanna and the Huluppu tree where people often confuse “lilītu” with the actual archetype or character Lilith; there was no Lilith in that story, just spirits needing to be expelled from a tree.

The Seer

Athena is often described by poets as being “grey-eyed” and there is symbolism behind this. According to Wikipedia the choice to describe her this way is quite deliberate; “In Homer's epic works, Athena's most common epithet is Glaukopis (γλαυκῶπις), which usually is translated as, "bright-eyed" or "with gleaming eyes". The word is a combination of glaukós (γλαυκός, meaning "gleaming, silvery", and later, "bluish-green" or "gray") and ṓps (ὤψ, "eye, face"). It is interesting to note that glaúx (γλαύξ, "little owl") is from the same root, presumably according to some, because of the bird's own distinctive eyes.” Athena is also often depicted as or with an owl which is all deliberate symbolism of her wisdom, keen perception, and foresight. There is a seer quality about Athena that is tuned into aiding justice and heroism.

Themes of the Asteroid Pallas Athene

Fear or repulsion of feminine expression in oneself

Deconstructing heteronormativity

Equality, democracy

Psychic vision, foresight

Companionship, sisterhood, brotherhood

Same-sex experiences, perceptions, and empathy

Creative vision

Justice

Intellectual power

Maternal absence

Pallas Athene being an asteroid, only with prominence in the birth chart will her themes and the complexes arising out of those themes be noticeable. Otherwise, Pallas Athene in one’s birth chart demonstrates where one tends to have strategic foresight/vision, where one meets Pallas Athene-like characters, and where one is called to serve justice.

Aspects to Pallas Athene

Sun-Pallas Athene

In hard aspects, such as a square or opposition, this contact can be quite troublesome and makes for complexes the individual will have to fight to overcome. The difficult aspects signify negative experiences with the paternal figure in their life which translates over into adulthood as having distrust in and difficulty with men. As most societies are patriarchal, these aspects tend to be harder for feminine identifying individuals. These individuals are keenly aware of the violence that can coincide with objectification, particularly the objectification of feminine expression. When this type’s innate identity is objectified, defences are put up and they reject and conceal their expression. Being viewed in a sexual nature in an unwarranted way kills the confidence in these individuals; it conflicts with how they view themselves as an entire being and their purpose. Being comfortable with one’s sexuality can be an issue in the more difficult aspects with this contact as well; there may be shame, repulsion, or rejection of one’s sexuality. To aid these complexes, therapy as well as companionship and empathy from people who share the same experiences or trauma is beneficial.

In positive aspects, such as a trine or sextile, we see the opposite of the crippling experiences in the negative ones. These individuals tend to be comfortable and even celebratory in either binary expression; they are often quite androgynous. They are also quite comfortable in their sexuality as well as they are firm believers in dismantling gender roles and heteronormativity. These individuals are fighters for people with Pallas Athene complexes and injustice in general. They have a tremendous amount of strength, empathy, and willingness to understand gendered, sexual, and political issues. These individuals can find their life’s purpose, fulfillment, and accomplishments through their intellectual creativity.

The conjunction brings out Pallas Athenian archetype within one’s character. These individuals will be very Pallas Athenian in that they will see within themselves the complexes that arise from both the positive and negative aspects. They often have quite a strong presence, cunning intellect, and the foresight vision.

Moon-Pallas Athene

In positive contacts, these aspects bring out the psychic nature of Pallas Athene– Pallas Athene’s foresight and the wisdom in part with that. These individuals are empaths and healers. In the positive aspects, this is Pallas Athene reconciled with the fact that she never knew her mother; in individuals, it is a deep connection with the maternal expression within them (through a Pallas Athenian lens) or a deep connection with the maternal figure in their life. The maternal figure in their life may have been very Pallas Athene-like or could have been a contributor to giving the individual the strength, wit, and wisdom that matches Pallas Athene’s archetype. Creative vision is evoked by emotional exploration

In negative aspects, such as the square or opposition, there can be an absence of a maternal figure. Just like Pallas Athena herself, this individual may have been raised by their father with their father’s interests on the forefront. As a result, feminine expression is often null or even despised or feared. These individuals may repress their emotions surrounding their own gender or sexuality issues. They can be quite defensive and unless the Sun has prominence in the chart, they can also disguise their expression and true identity. These individuals can be quite masculine, over-functioning, and independent; they fear depending on others and self incompetence. To aid these complexes, they need to surround themselves with people that can bring out the softer nature hiding within them; they need to see that being nurtured and loved does not diminish their strength and ability.

The conjunction brings out complexes that resemble both the positive and negative aspects, though the maternal figure is most often present like in the positive contacts. Psychic vision is very potent with the conjunction and there is an urge to serve justice with it.

Mercury-Pallas Athene

In positive aspects and the conjunction, we see individuals with immense creative intellect. These people are often leaders in the fields of science, art, politics, and law. People look to these individuals for their ability to strategize and look at the whole picture. As Pallas Athene touches the planet of communication, these individuals will often have a powerful voice, especially for those who don’t and are in need of justice. They can make for great advocates for gender and sexuality issues.

In the negative aspects, such as the square or opposition, we see individuals who struggles to have a voice on gender and sexuality issues, or just in general. These people can find their voice by making connections with others who share similar issues and by being part of a group setting.

Venus-Pallas Athene

The Venus contacts to Pallas Athene can be quite similar to the Sun contacts in that the complexes surrounding feminine expression tend to be the same. In the negative aspects, such as the square or opposition, there is the same repulsion towards feminine expression in oneself. It stems from fears developed from observing a patriarchal society’s perception of women and sometimes trauma. There may even be internalized misogyny present as these individuals have a tendency to reject traits that could be perceived as feminine, as they equate femininity to weakness and incompetence. These individuals present themselves as tough, rigid, unlike the others, and often androgynous or hyper masculine. They fear being taken advantage of and avoid any sign of weakness at all costs. Their inability to let their guard down can hinder close relationships; these people often deny themselves of romantic connections and keep everyone at arm's length. To cope, these individuals will put all of their focus into creative outlets and put their accomplishments on a pedestal over relationships. To aid rigidity and to reconnect with feminine expression, these individuals need to surround themselves with strong figures who are very confident in their feminine expression; they need role models and will find strength in numbers (being part of a support system). Re-education may need to be involved in the healing process as well. Exploring further with where ever Venus is in the individual’s chart and honing in on Venusian activities can really benefit this individual’s self acceptance, inner beauty, and sexuality.

In the positive aspects, such as the trine or sextile, there is radiating confidence, beauty, strength, creativity and merging of masculine and feminine energies. In these aspects is where Aphrodite and Athena meet eye to eye. These individuals are often very comfortable in their sexual expression; they tend to be drawn to feminine energies. As Pallas Athene aspects tend to make for, these individuals also tend to be express themselves androgynously, but are comfortable with feminine expression. They are very celebratory over it, similar to the Sun aspects. These individuals tend to be quite independent, but definitely not closed off. There is often an urge to utilize their strength and confidence in advocating for women’s right and issues, and it should be encouraged as these individuals are often the perfect candidate to advocate on these issues. These individuals possess some healing abilities as well and heal others through empathy. Empathy for same-sex experiences is a prominent theme for both the positive and negative aspects; the natural connectivity or alliance with one’s gender makes them feel protected and valid.

With the conjunction, many of the themes found in the Venus-Pallas Athene aspects are intensified. Pallas Athene is somewhat personified in the individual and there is a much more radical need to demonstrate their autonomy over how they choose to express themselves. Expressing themselves through creative means is often very important and almost always contains a very Pallas Athenian message.

Mars-Pallas Athene

In positive contacts, such as a trine or sextile, Mars emphasizes that accomplishments and success can be found through Pallas Athene. Individuals with these aspects make excellent leaders, people want to nominate this type of individual to be in control and make the decisions. These individuals have a lot of drive, strength, and prestige, as well as empathy and compassion that does not diminish those qualities. There’s a keen awareness for underdogs and an urge to aid those beneath them. In feminine identifying individuals, utilizing masculine traits yields success, and in masculine identifying individuals, utilizing feminine traits yields success. Strong, lifelong companionship with the opposite sex is a common theme with these aspects as well.

With negative aspects, such as a square or opposition, there can be intense strife with the opposite sex. Additionally, strife with one’s own gendered expression; either hyper masculine or hyper feminine to conceal one side of the binary. Much of the repulsion towards one specific expression is due to societal conditioning as well as upbringing; it’s a defense mechanism to protect themselves from being perceived as either too weak or too harsh. There can be a lot of anger within the negative aspects as well; it would be best to redirect this anger towards a cause, such as advocating for women’s rights, men’s mental health support, protecting children (particularly if the 5th house is involved), environmentalism, sexual freedom, religious freedom, and so on. Therapy and support groups can aid self resentment and resentment towards the opposite sex.

With the conjunction, Pallas Athene is personified in the individual when they are challenged or angry. They may be quite radical, independent, and domineering; they are always in charge. They despise being perceived as incompetent or submissive. Pallas Athene’s strategic and cunning qualities are apparent in the conjunction as well; these individuals are not people you can fool or surpass, especially when a goal is on the line.

Jupiter-Pallas Athene

In all Jupiter contacts, Pallas Athene’s psychic foresight is present. Individuals with these aspects are blessed with intuition and wisdom. They hold valuable advice and counsel to others as well as themselves. They tend to be respected by many; their companionships and kinships are their armies.

Particularly in the positive aspects and the conjunction, these individuals would do well in politics, law, and creative arts. Serving justice is particularly important to this asteroid when in contact with Jupiter. Symbolically Jupiter is Zeus, Athena’s father, who loved and praised Athena the most out of all of his children. This may translate as an individual who had a similar positive relationship with their father; a father who is particularly proud of the individual, who may also could have been quite Jupiter-like. It also signifies the urge to be the same type of parental figure to their own children.

Saturn-Pallas Athene

With positive aspects, such as a trine or sextile, there is creative focus and prestige. The hard work from these individuals doesn’t go unnoticed. Saturn amps up Pallas Athene’s urge to serve justice; there’s often feelings of responsibility over something as big as society. These individuals would do well in law, politics, or any position of leadership. Reconstruction of societal values is a common theme with these aspects. These individuals seek change for how society perceives gender expression, sexuality, and politics. On a different side of the same coin, these individuals may have a bit of rigidity within themselves when it comes to true self expression, particularly with expressing femininity. Though, the negative aspects are considerably more stark than the positive.

With negative aspects, such as the square or opposition, there is almost always issues with the paternal figure or one of the individual’s parental figures (particularly if one parent is a stern, overfunctioner). The individual may have had high expectations held against them at a young age or there may have been a preconceived notion from a parental figure that the individual is incompetent due to how the individual expresses themselves or based on the individual’s values. The individual will feel inadequate to their peers, especially to a specific sex. There is rigidity in their expression, as mentioned earlier. These individuals may overcompensate for gendered stereotypes inflicted upon them. These individuals need to redirect their purpose for themselves and not for others. Therapy may aid them in relearning that they are not put on this planet to meet someone else’s expectations. Once confidence is regained, they can reign the creative focus, prestige, and leadership qualities that the positive aspects signify.

The conjunction can demonstrate qualities from both the positive and negative aspects and is much more potent and noticeable out of all of the Saturn aspects.

Uranus-Pallas Athene

In all Uranus-Pallas Athene contacts, there is an urge to come together with people to make change. Here is where Athena builds her army and strategically conquers and destroys harmful constructs. The aspects with Uranus are all about world betterment, particularly with issues dealing with gender and sexuality.

In positive aspects and the conjunction, Pallas Athene’s geniusness is very apparent. Individuals with these aspects often find success in sciences or anything that utilizes creative intellect.

Neptune-Pallas Athene

In all Neptune-Pallas Athene contacts, individuals can find access to psychic power and strong intuition. These individuals have dreams of prophecy and can see far into the future. These individuals also tend to have a knack for arts that require a lot of technicalities and vision such as music and film.

People with the conjunction may find their psychic powers to be particularly potent and these people are often very spiritually aligned. Their binary expression has special importance to their spirituality. Spiritual devotion is merged with their self expression; whether that be the type of spirituality they practice or perhaps a special relatability to specific deities or energies.

Pluto-Pallas Athene

These aspects are most apparent when it’s the conjunction or accompanied with a personal planet. These aspects give an individual the urge to really explore the psychology behind Pallas Athene complexes. There is dedication to understanding difficult constructs, particularly gender, sexual, social, political constructs. This urge is accompanied with the desire to transform the world’s beliefs, similar to the Uranus aspects.

In negative contacts, these aspects can signify this urge stemming from a place of trauma and wanting to heal and rebuild the self.

Pallas Athene conjunct or in the house of the Ascendant

Athena is personified in the individual. These are people of strength, prestige, wit, and beauty. They possess the creative vision this world needs. These people break societal norms through their self expression and defy gender and sexual stereotypes.

Pallas Athene conjunct or in the house of the Imum Coeli

Here the asteroid is quite concealed as it is furthest away from the spotlight (midheaven) and squares the ascendant. These people tend to not outwardly express Pallas Athenian qualities unless certain aspects demonstrate otherwise. Pallas Athene’s psychic qualities are more awoken here as the individual identifies Pallas Athene inwardly.

There may be a very Pallas Athenian person in this individual’s family or they are somewhat of a Athena-archetype themselves to their family (most loved child, most outspoken, known for creative intellect, etc.)

Pallas Athene conjunct or in the house of the Descendent

These individuals encounter or even draw in many Pallas Athenian-like people. Either that because they are drawn to these types of people or their projection out into the world brings them about as a way of balancing the individual or teaching them something they don’t see within themselves. These individuals tend to have a particularly fondness (platonic, romantic, or sexual) to their own gender.

Pallas Athene conjunct or in the house of the Midheaven

Here the asteroid is furthest away from home (Imum Coeli) and squares the ascendant. These individuals may possess some of the complexes Pallas Athene signifies on gender and sexual expression. There may be maternal absence and there is almost always a hyperfixation on career and success over relationships. These individuals are often the leaders in their workplace, if not, they still walk to the beat of their own drum and tend to be well respected. They may confuse the respect they earn by how they express themselves rather than their actual accomplishments. This can cause some difficulty around being true to oneself in terms of self expression. They need to seperate who they are being a factor in what they can accomplish and be known for.

© - @star-astrology 2021 / All rights reserved.

431 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since the very conception of the motion picture, the LGBT community have been represented on-screen in some form. An early example is Algie the Miner (1912), a short silent film which follows the effeminate Algie (Billy Quirk), who enjoys kissing cowboys. In order to marry someone’s daughter, he heads west to prove that he’s a man. While this is quite an outdated stereotype of being gay, the portrayals have varied greatly over time. Only recently is LGBT representation becoming more positive and common. However, when it comes to portraying bisexuality on-screen, it still seems to be a difficult task.

Many narrative tropes have been birthed through filmmakers trying to show sexuality on-screen and most of them contribute directly to the overall erasure of bisexuality in cinema – usually with ambiguous portrayals, negative stereotyping and characters needing to pick a side. Not all instances are problematic, but their prevalence isn’t helping to combat the stigma that bisexual people face. There are three main tropes when it comes to depicting bisexuality, which is infidelity, picking a side, and the horrible husband. They’re usually found together in a common narrative that erases bisexuality, whether intentional or not.

Infidelity

There’s a long-standing stereotype that bisexual people are more likely to cheat on their partners and are incapable of commitment. This is a trope that is heavily carried in some of the most well-known depictions of bisexuality. Typically, a female protagonist is engaged or married to a man, but she meets a lesbian woman and they become involved sexually and romantically, leaving the protagonist torn between two lovers. This happens in Imagine Me & You (2005) when Rachel (Piper Perabo) falls in love with lesbian flower shop owner Luce (Lena Headey), who provided the flowers for her wedding to Hector (Matthew Goode). It’s a fairly average film that could’ve been amazing had it acknowledged Rachel’s bisexuality, but it’s still one of the better ones considering Perabo and Headey have amazing chemistry.

For some reason, bisexual characters are often in serious relationships when they’re suddenly sexually awakened. This happened to Rachel right after her wedding because she happened to meet the right woman. While this type of experience does happen in real life, it’s always the go-to narrative for films about women realizing they’re not one-hundred-percent straight. In these instances, the same-sex love affair acts as the conflict within the narrative – this can create good drama when done right, but it gets boring and bisexual characters deserve better than constantly being portrayed as cheaters. People are not more promiscuous or likely to cheat on their partners because of their sexuality, but these tropes are constantly telling people otherwise.

We deserve to see bisexual characters whose sexuality isn’t the main narrative focus or who at least explore their sexuality outside of a relationship. Appropriate Behaviour (2014) is a good example of this as Shirin (Desiree Akhavan, who is also the film’s writer and director) is a bisexual Persian American woman who is keeping her sexuality a secret from her judgemental family, while also attempting to rebuild her life after breaking up with her girlfriend. Seeing bisexuality portrayed on-screen is another place where people pick up more stigma or acceptance, and with bisexuality it, unfortunately, seems to be the former. This is why bisexual filmmakers like Akhavan are better suited to portraying the experiences of bisexual men and women than others.

Picking A Side

When the protagonist is in conflict with her sexuality, the people around her usually wonder if she’s a lesbian now – despite them being engaged or married to a man. This can be seen in Below Her Mouth (2010) where Jasmine (Natalie Krill) begins having an affair with Dallas (Erika Linder). When her husband finds out, he tells her “You’re a lesbian” but she tells him that she loves him and nothing has changed between them. It seems impossible to grasp that a person could be attracted to both men and women. Bisexuality is erased.

Some films insinuate that the protagonist isn’t necessarily bisexual or even a lesbian, it’s just that they’re attracted to this one woman only and no others – they’re an exception! This is the kind of impression you get from Below Her Mouth, but also from other films such as Imagine Me & You and Elena Undone (2010), which isn’t particularly helpful for lesbian representation either. In Imagine Me & You, Rachel tells Hector “You are my best friend. That was enough before, and it will be enough again.” This implies that Rachel was never truly attracted to him in a romantic sense, thus implying that she’s a lesbian. While this could be a case of compulsory heteronormativity, it seems problematic as it’s never discussed or explained. Avoiding discussions about sexuality – as most of these films do – are what contribute to this trope massively and result in misinterpretation and erasure.

Films as new as Netflix’s Alex Strangelove (2018) also feed into the idea that bisexuality is a stepping stone to picking a side. Alex (Daniel Doheny) prepares to lose his virginity to his girlfriend but finds his plans derailed when he’s attracted to another boy. He spends most of the film questioning his sexuality and at one point thinks he’s bisexual. The film does highlight biphobia which brings attention to this problem, so it’s disheartening at the end when Alex realizes he is gay and not bisexual after all. The set up for Alex Strangelove was perfect for a bisexual love story and, while it’s still positive LGBT representation, it’s a shame it didn’t stick with that. It’s even rarer to see bisexual men portrayed on-screen, so it would’ve been really rewarding.

It’s important to acknowledge that bisexuality is a comfortable place for some people to be while they’re trying to accept that they are gay – and there’s nothing wrong with that. However, there still seems to be some widespread discomfort when it comes to sexuality being fluid. For bisexual people, there isn’t any side to pick – they’re not torn between polar opposites, nor are they confused. They aren’t on the fence, they’re on both sides of the fence. Nevertheless, films continue to portray bisexuality as a personal conflict that needs resolving, and it does this by putting bisexual characters in a situation where they’re having affairs. This makes their sexuality the narrative conflict, which is wholly problematic in itself.