#blake snyder beat sheet

Text

The children yearn for the mines thing but it's just me, yearning for a literary analysis assignment after finishing a book.

So because i have a Film degree, i did the Blake Snyder beat sheet for this novel lol

my Jane Eyre beat sheet

Opening Image - Jane's abusive childhood

Set-Up - Jane is desperate for love and acceptance, desperate to find family and a home where she will feel appreciated.

Theme Stated - Forgiveness is important in love.

Catalyst - Jane is sent to the super religious school where she learns to double down on her people pleasing instincts. Maybe someone will love her and accept her if she is obedient and useful and selfless– this school and its teachings snuff out her sense of self-worth.

Debate - Jane reveals that she wants her abusers to suffer. Helen tells Jane about god and how crucial forgiveness is, even for those who wrong you.

Break Into Two - Jane takes her future into her own hands, taking out an advertisement and goes to work at Thornfield. She can be useful and find purpose in caring for others.

B Story - Jane meets Rochester– who is not attractive or kind, so it puts her at ease. He puts no effort into being "good" and does not claim or aspire to any virtues her teachings were based on, which is refreshing. He values what she has to say, appreciates her gifts and overall personality, and makes her feel like she is actually worthy of attention.

Fun and Games - As Jane and Rochester develop a rapport, she begins to feel important and useful, and takes pleasure in being of service to him. Even though she worries that he is in love with Blanche Ingram, he proposes to her. She realizes that he appreciates her for who she is because she is worthy of love. She does not have to fade into the background as she was taught.

Midpoint - Rochester is not only already married, he keeps his wife locked in the attic.

Bad Guys Close In - Jane is determined to respect Rochester’s marriage, even at the cost of her own happiness. He loves and accepts her as she is (yay!) but she cannot forgive him for breaking his marriage vow (boo!). Her want/goal was to find people who loved her as she was. Her need is to learn to forgive people so she can be receptive to and reciprocate that love.

All Is Lost - Jane leaves Thornfield Hall. She rejects Rochester’s love, rejects her job, her home– everything she found and cultivated in this new life she made for herself and winds up starving and cold and penniless and alone. Worse off than when she left the Reed’s house or the school in the beginning.

Dark Night Of The Soul - The Rivers take Jane in and give her a new family to belong to, a new vocation, a chance to live independently, but without the kind of love she had from Rochester. St. John proposes marriage for the purpose of making her a missionary’s wife. It will be a platonic marriage, at the service of god, where she will have to be selfless and deny her own personal desires. This is the opposite of the life she was leading at Thornfield Hall where her opinion was valued and her appetite for love was well-fed, and her weird little delights in being called an elf and endearingly teased were satisfied. She will not get that as a missionary’s wife, where the emphasis will be on piety and goodness. St. John appreciates her, not for who she is, but for what he can make her. She hears Rochester crying out for her in the night and knows she has to go back to him.

Break Into Three - Jane returns to Thornfield to find it has been burned to the ground and Rochester is badly injured. He is free to marryy her now, he even needs her help so she will definitely be useful if she stays. She has to forgive him if she wants to be with him now. And if she wants to be with him now, she needs to reject being a people pleaser and marrying St. John to live as a selfless missionary’s wife; she knows her worth now. She will not sacrifice her happiness, she wants Rochester and she will have him.

Closing Image - Jane and Rochester live happily together. They have children. She loves her life. She feels useful and loved and does not have to sacrifice anything to be this content. Additionally, St. John is doing his missionary work and never marries– the epitome of the selfless, people pleasing life she was bound for if she had never learned her worth or how to value herself as she is, which is what Rochester’s love has given her.

#i wrote out this beat sheet just so i can write my ouat fic#blake snyder beat sheet#jane eyre#literary analysis#charlotte brontë#liveblog of me reading#long post

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you ever see something and think ‘wow, I’m a people-pleaser, but not that much’

#i lurk on r/craftsnark because it’s surprisingly entertaining and it seems like every other week they have the debate#about whether it’s okay to sell something you knitted from a pattern#like say if you bought a hat pattern from somebody and made a ton of hats based on said pattern. is it okay to sell those knitted hats#the thing is that all of it is a moot point imo because regardless of what you think about it ethically; it is legal#you can only copyright a pattern. not the objects made from the pattern. it Can be a breach of contract law but the contract#has to be proven#anyway so with all this in mind; this week there was this thread where someone had been messaged by a designer#who was like ‘hey can you stop selling things made from [x pattern] that’s against my terms of use’#and literally they were way too civil about it#i consider myself to be a doormat but i still would’ve been like ‘i’m not going to stop. if you can find a law to sue me under#we can settle this in court. until then good luck getting the stick out of your arse’ and then i would’ve blocked them#i mean can you imagine this happening in any other field? if i look up.. idk… a list of instructions on how to build a desk#and then i decide i want to sell the desk i made.. is the writer of the instructions going to be in my inbox? i highly doubt it#do the people who make art tutorials sue anybody whose art gets better based on their directions?#did blake snyder sue everybody who used a save the cat beat sheet to plan their novel????#maybe not the same exact thing but it is some ridiculous shit. it’s one of those ‘debates’ i’m just sick of seeing#because the answer is so obviously ‘just do it’#it’s legal and how can it possibly be morally wrong. you’re taking nothing away from the designer. no one who wants a hat#is going to buy a piece of paper instead. it’s two separate markets#i’m sick of even talking about it. thanks for reading this nonsense if you did#personal

0 notes

Text

Kagurabachi's Popularity: Familiarity Through Structure

Having a degree in writing and media is so fun because I can write an essay on why Kagurabachi can be defined as well written through craft standards and attribute its popularity overseas to its structure, which is framed similarly to western movies.

And I am!

After this interview confirmed that Takeru Hokazono, author of Kagurabachi, is a huge fan of western films, I went back to this idea I was playing with in October when KB had less than ten chapters. I had been reading since day one, and I knew it was good, and other overseas fan knew it was good. But what made it so good to us, overseas?

I made a quick thread on it on my Twitter account (that I never posted) where I mentioned Blake Snyder's Save the Cat book on script writing and story structure. I also brought up characterization and how it would've been really popular in my comic book class from undergrad. This thread discussed both Chihiro and Sojo, and the quick yet steady pace of the manga has given us more characters and moments to pinpoint. To not overwhelm myself, I'm not going to discuss the craft of characterization (maybe another time), and I'm not going to do a beat sheet for Sojo. For now, I'll try to stay under the first arc to map out why Kagurabachi has so far moved like a high budget film in manga form. So, spoilers ahead!

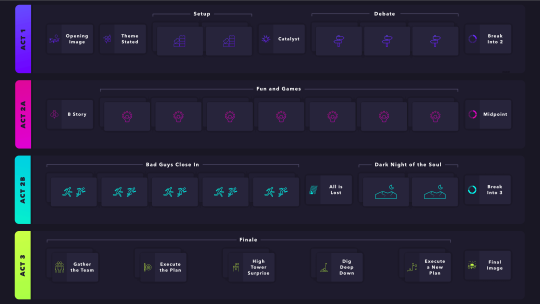

A quick lesson on Save the Cat, its three main characteristics are:

Three act structure

Fifteen plot beats

Mostly applied to American Hollywood films

One of the biggest things I noticed right away was the resemblance a lot of the chapters, even the story as a whole, had to Snyder's beat sheet. This beat sheet that comes from Snyder's book is somewhat of an industry standard, so a lot of movies, even those that preceded Snyder, go through this structure of Act 1, 2, and 3. Snyder just identified the parts and broke them down to fifteen beats. Plus he dubbed the save the cat moment:

A decisive moment in which a protagonist demonstrates they are worth rooting for. Having the protagonist save a cat can be literal or figurative.

This was something KB needed and did have to have us warm up to Chihiro who post time skip, just gave gloomy orphan energy in the previous chapters. Here, Char would be our cat. Chihiro chose to save Char and chose to protect her, and continued to fight for her until she was rescued. He made this choice even before it's revealed that Char's mother died for her, something that would parallel Chihiro. This is what got readers to see him three dimensionally after being introduced to him. He's still the caring little 14 year old we saw at the start, who continues to take care of the innocent despite the tragedy he's been through. It is only natural for us to care for him, too.

Above are the fifteen beats of Save the Cat and although KB on occasion doesn't hit all fifteen exactly as specified, especially final image as it's continuing, the song and dance is quite similar. Here are examples of The Dark Knight (2008) and Inglourious Basterds (2009), two movies that have inspired Hokazono's work.

Before Chihiro meets Char, we get his opening image of him and his dad forging which is works well as the entire story revolves on the consequences of them creating weapons. We get the set up to his world where he lives with his dad who made famous katanas that wield the power to end a war. The theme is stated, and it's not kept a secret: The katanas they make are weapons made to kill people. Are they willing to carry the burden? In another variation of this question, is Chihiro willing to carry the burdens unintentionally passed down by his father?

The catalyst is his father's murder that catapults him into seeking revenge and recover the katanas.

Now, for the rest of the story, this structure can be applied to the first 18 chapters or even 1-3 chapters at a time which in my opinion, is kind of insane. There's story telling inside the story telling, and these moments are both subtle and grand, signs of a strong and captivating writer. Hollywood would kill for a script like this these days. In order to get you to believe me how prominent these beats are, I'm going to do arc one and Daruma's story. The main story line should be around act one and two right now as of chapter 20, if we want to get down into it, but if anything, this feels like it's moving like a second "movie."

Overall, this structure that comes from Hollywood movies can be identified in multiples parts of Kagurbachi's storytelling. I was going to do beat sheet's for Char and Sojo's stories as well, but I think this is enough of an example of a bigger picture versus smaller. Although other mangas also fall into three act structures, as most story telling does, KB masterfully uses the 15 beats to its advantage. I believe the familiarity of this pace is what hooked oversea audiences, and aside from that, the characters that quickly capture us.

Very quickly, because I don't want to make this about characterization, Chihiro is well written through his past, who he chooses to kill and save, his dialogue that can be surprisingly vulnerable at times, and his cool façade that melts because of how hot he truly runs. He is also straight up a badass. We get handed Char's background in an "all is lost" segment as well as some lore that can present her as a resource for the main cast. We see Azami's phone background photo that's minimum 3+ years old- a government employee with a soft spot for his friends, one who he is still clearly grieving. We get one tiny yet so fucked up bit of Sojo when we see him get a flashback where he's a child and his single dialogue of "I truly love Kunishige Rokuhira," that launched his type of villainy in the maniacal fanboy category. Who does it like that? Nobody but Takeru Hokazono.

Thank you for reading this essay! I do have two other essays drafted, one on Sojo's possible return (I'm a delusional Sojo fan) and just his overall significance and impact as the first villain even if he doesn't return, and on Hiyuki plus servant leadership versus self service.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

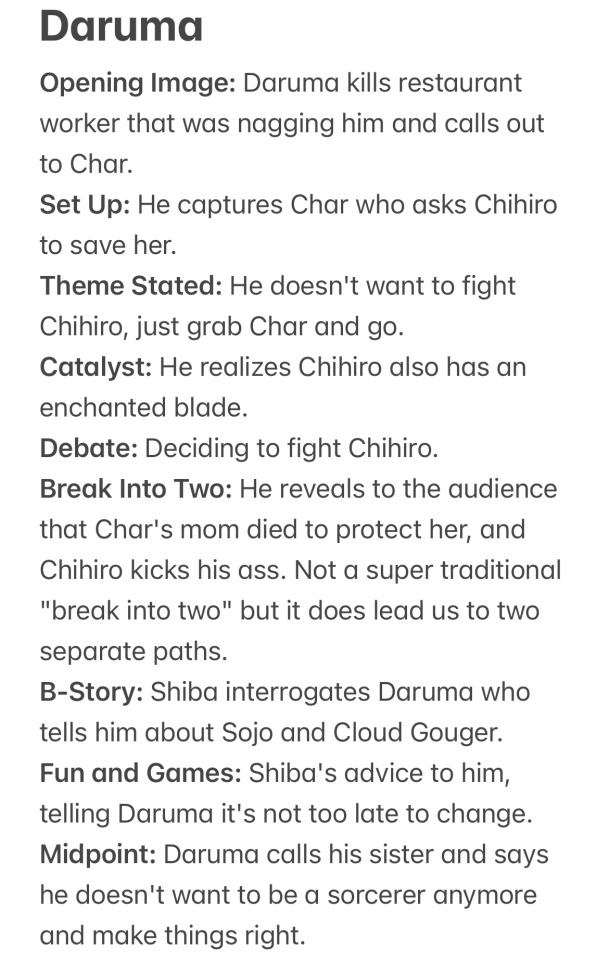

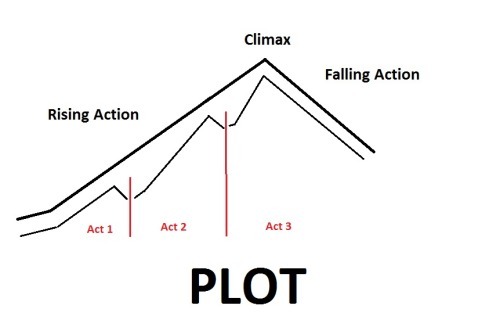

Strong Act Structure Creates Stronger Stories

by @septembercfawkes

In storytelling structure, people use the term “act” rather broadly and vaguely. Most in the writing community break stories down into three acts: beginning, middle, and end. But if you asked many writers what an act actually is, they would probably give you blank stares.

Despite acts being key structural units in stories, they don’t get a lot of attention.

And when they do, they are often treated simply as containers to fill with beats from a beat sheet.

Luckily, the basics of acts aren’t too hard to grasp, if you already know the basics of structure.

And once you grasp acts, your whole story will have not only better structure, but better pacing and better direction.

So let’s unpack the act!

As mentioned, those who usually give the act any mind, are often following a “beat sheet.” This is a list of key moments (or “beats”) that are supposed to happen in a specific order, and usually, at a specific time, to make a story more satisfying (put simply). Beat sheets can be very helpful and very effective. Two of the most popular are Save the Cat! by Blake Snyder and Vogler’s version of The Hero’s Journey. Another common structural approach is 7 Point Story Structure.

Often beat sheets will be separated into acts, so if you are familiar with them, you may have some understanding of what’s supposed to happen in each act.

If you aren’t familiar with them, that’s fine too.

Basic Story Structure

I’m going to explain acts from the bottom up–and we’ll get back to the beat sheets for those who like to “beat” out their stories.

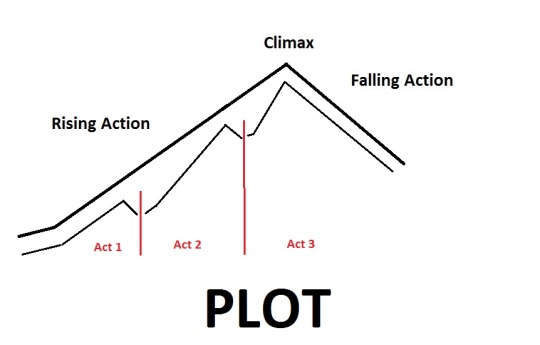

At the most basic level, the structure of a story (almost) always looks like this:

It has a rising action, climax, and falling action.

If we zoomed in a little more, there would be an inciting incident. This is the turn in the beginning of the story that kicks off the main plotline–it often appears as an opportunity or a problem for the protagonist.

Charlie Bucket finding a golden ticket.

Peter Parker getting bit by a radioactive spider.

Boo coming into Monstropolis in Monsters Inc.

These are all examples of inciting incidents.

From there, the story escalates, more or less, until it gets to the climax, where the main conflict between the protagonist and antagonist hits a peak and gets resolved. This creates a turn that then leads to the falling action.

That’s basic structure.

Basic Structure and Structural Units

But it’s not only basic structure for a story as a whole, it’s also basic structure for just about any solid structural unit. Ideally, scenes should have this structure, sequences should have this structure, and yes, acts should have this structure.

Each unit fits inside the bigger unit, like a Russian nesting doll, or a fractal.

The difference is that, the smaller the structural unit, the smaller the impact.

So the climax of a single scene will be smaller than the climax of a sequence. (This term isn’t used very often, but a sequence is a string of related scenes, that don’t fill up a whole act.)

The climax of a sequence will be smaller than the climax of an act.

And the climax of an act will be smaller than the climax of the overarching story.

Basic Act Structure

Nonetheless, other than the story as a whole, the act is the biggest structural unit. This means each act should crest into a big turn in the story.

It’s not just that the story has one major peak–a turning point–at the end.

It should have several big peaks along the way.

It should also have several “valleys” along the way.

While the overarching story is escalating in general overall, it still has rises and falls in each act.

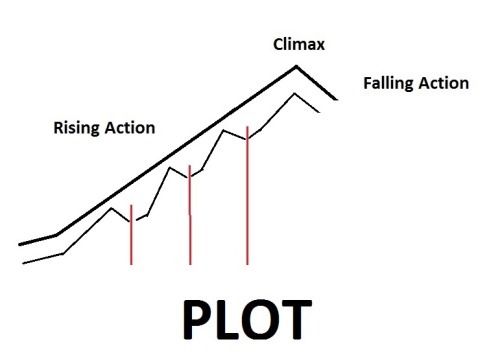

Most commonly, people view stories as having three acts.

This means the structure will look somewhat like this:

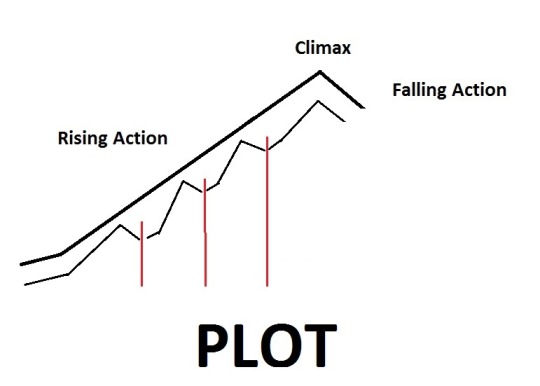

It’s also equally common to split the middle act in half. Frequently, in the middle of the second act, there is a major turn, called the midpoint (you may have heard of it). If this moment is major, it’s often more helpful to picture the structure with the second act split into two, something like this:

One may arguably call this a four-act story, but to keep with the most commonly used terms, it’s probably better to call these pieces, Act II, Part I & Act II, Part II.

When you look at this structure, you may realize something . . . there is no saggy middle! There is also no boring beginning, or lackluster end.

This is because there is a rise, peak, and fall within each act (and arguably two in Act II).

Frequently, people divide these act pieces into quarters. Not every writer likes using percentages, but it’s the best and easiest way to indicate when and where something in a story should typically happen–so we’ll use them.

Act I: 0 – 25%

Act II, Part I: 25 – 50%

Act II, Part II: 50 – 75%

Act III: 75% – 100%

Please note that the percentages aren’t laws; they are more like guidelines. But we need the guidelines to even have a proper conversation about acts. Once we understand the guidelines, we can play with variations for different effects, but we need to lay a foundation first to get anywhere.

The beautiful thing about this, though, is that you know you need to hit a peak in each of these quarters.

Now, occasionally, writers will cut some or all of the falling action off the structural unit. This is rare for the overarching story (but it does happen!). It is more common for smaller structural units. So don’t panic if all your units don’t have the “fall” into the valley.

Acts and Structural Pacing

The point is, you have peaks and valleys.

And it’s helpful to have them in the proper places. Why? Because this is what controls structural pacing.

Pacing is more than word count. In fact, pacing more closely links to structure. When the structure of any given unit is solid, the pacing will almost always be exactly what you need. The exception to this is when you are looking at the lines themselves–that’s when things like word count become more important.

Generally speaking, solid structure = solid pacing.

This is why when you understand acts, you’ll be less likely to have pacing problems in beginnings, middles, or ends (no saggy middles!).

Pacing gets tighter the closer it gets to the peaks, simply because the plot itself is becoming more intense.

Then it gets more leisurely and loose in the valleys, as we fall and/or begin the next climb.

Each Act’s Climax

Act I

So, when you are writing the beginning, you know you need to be climbing toward a big turn, which will hit before the middle.

What is this Act I climax?

Well, depending on what approach you are using, people will call it different things. (This is where those of you who are familiar with beat sheets pull yours out.)

In Save the Cat! This is the “Break into Two” beat.

In Vogler’s Hero’s Journey, this is “Crossing the Threshold.”

In 7 Point Story Structure, this is “Plot Point 1” (sometimes alternatively called “Plot Turn 1”).

If you aren’t familiar with any of these terms, that’s fine, but know Act I has a climactic turn.

This climactic turn works by locking the protagonist with the main conflict. It is typically marked by the protagonist’s choice to step forward, through a “Door of No Return” (i.e. Crossing the Threshold) or a “Point of No Return” (i.e. plot point). It’s what “breaks” the story into Act II.

The protagonist definitively chooses to go forward on the journey of the primary plotline. This is then usually followed by a transitional segment, that takes us into the “valley.” . . . There is a lot more I could go into here, but it’s beyond the scope of this article, so let’s move on.

The falling action is often a reaction segment–where the character is reacting to what just changed at the peak. Once the character has at least some sense of their situation, they usually start “climbing” toward a current goal (rising action).

Act II, Part I

Near the halfway mark of the story, you typically hit a climactic peak again. A big turn. People most frequently call this the “midpoint.” It usually involves the protagonist gaining new, important information that helps him move forward more aggressively, or rather, actively, against the antagonist. But it may be marked by a big victory or failure for him too.

The point is, there is a turning peak.

. . . which leads to “falling” into a valley . . .

And again, the falling action is often a reaction segment to whatever big change–revelation or action–just happened.

Act II, Part II

Once the character gets some sense of the situation, you know what she’s going to do? Start the climb toward the current goal. Rising action.

And of course, the climb is never easy. Every climb has conflict and stakes–that’s the only way to escalate the story (in other words climb the rising action).

She hits another major turn.

In Save the Cat! this moment coincides with the “All is Lost” beat.

In Vogler’s Hero’s Journey, it’s “The Ordeal” beat.

And in 7 Point Story Structure, this is (arguably) Plot Point 2 (but there is some ambiguity on how that term gets used in the writing community).

If you don’t know those terms, that’s fine, but just know that this is the major climactic moment of Act II (Part II).

And, most frequently, it leads to the biggest “fall” of the story–a big lully drop to a low, low valley. It’s usually the largest reaction segment of the story.

Well, guess what happens next?

Act III

After the character has taken some time to wallow in his failures, he’ll find his footing and start the last climb–to Act III’s climax, which is (almost) always simultaneously the climax of the whole story.

And that’s the basic structure of the story, through acts.

Acts and Inciting Incidents

Now, if we were to zoom in a bit more, we would likely find that each act also has an “inciting incident”–it’s usually what kicks off the next climb. It’s what gets the character to leave the valley and come up with a plan about what to do next (whether or not the plan plays out as intended).

The most recognizable one in storytelling approaches (other than the first one, in Act I) is Act III’s.

After Act II, Part II’s major lull, usually the protagonist gains something that pulls her out of the lull. If you are following along with your beat sheets . . .

Save the Cat! calls this “Break into Three.”

Vogler’s Hero’s Journey calls this, “Reward: Seizing the Sword.”

And (this is where the ambiguity creeps back in), this is often lumped in with “Plot Point 2” in 7 Point Story Structure.

But Act II will also usually have its own “inciting incident,” something that gets the character on track for the next climb.

And . . . if we went much deeper into structure, I’d probably need to fill up a whole book. So, we’ll end there.

Just make sure to mind the peaks and valleys of your acts–your story, agent, editor, and readers will thank you for it. Even if they don’t recognize what you are doing, they feel it.

(And you’ll probably thank yourself for it too!)

217 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hewwo~ I love the comics you guys make! Can I ask about what your writing process is like? Do you follow some sort of 3-act structure template, or have some other fun tools? Where do you get your ideas from? Sorry if that's a lot to ask! I want to be a strong writer like you guys!

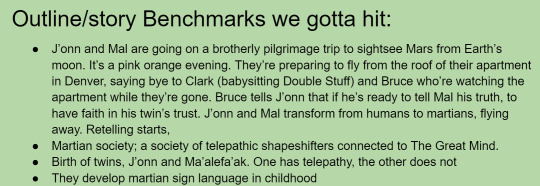

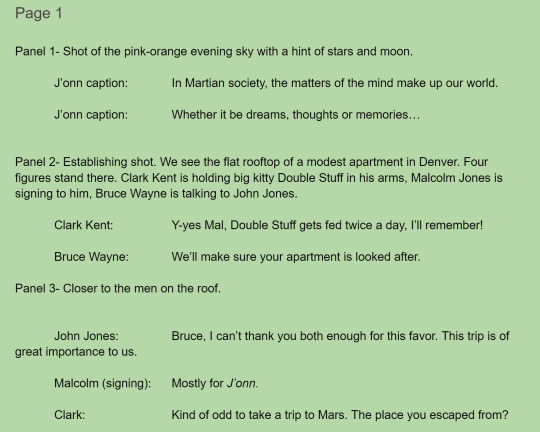

Hello there! :> thank you for the kind words!!

If I had to describe my writing process it would be working "general to specific". So I would have a general idea for a story, work out the big events, then flesh out the details down to dialogue and character acting (I like to have that figured out in the script early so once I sketch/thumbnail the comic I'm not mentally overworked).

Elevator pitch -> Outline -> Story Breakdown -> Script

Throughout the process I'm always keeping in mind what the theme of the story is, making sure it's not lost in the process. The 3 act structure comes naturally from feeling the story out, but it's good to revisit sometimes if you feel like your story is missing a beat or needs rearranging. I usually check out Blake Snyder's beat sheet when I feel something's lacking but I don't treat it like strict rules to follow- more like a guideline.

For where I get my ideas from, lately it's a mix of lived experience that I want to see more of in fiction or a twist on existing stories. "Princess Kaguya x Little Prince but about a trans masc Indonesian boy going through culture shock" or "Martian Manhunter but his evil twin brother is misunderstood and not evil". Stuff that would be fun to write and gets me excited just thinking about them.

I hope that was helpful! And good luck on your writing!!

#askjesncin#writing advice#my script is green to prevent eye strain#it's not cuz i love martian manhunter so much however-

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

when you are writing a fic do you have most of it planned out beforehand or do you kind of make it up as you go along?

In the past, I've mainly identified as a plotter.

My typical approach to a story was to use Google sheets and write out mini summaries of each chapter. I used Blake Snyder’s story beats, the 27 chapter method, Dan Wells’ seven point story structure, the Highway and Service Road method from Jane Cleland’s book, “Mastering Plot Twists” and everything in between.

However, after composing the blueprint for a story I’d often be bored and struggle to write the actual novel. Knowing what happened next killed the vibe. Another issue that I saw in my writing was that my character development and their growth cycles sometimes felt stilted and forced. Whether or not I could capture the essence of a character was a roulette of hit or miss.

Because of that, I approached TPATL in a different manner. I felt like I finally knew structure well enough that I could pull off a character driven story - I’d attempted it before, around 2018, and it ended disastrously. TPATL exists primarily because Lloyd was the perfect character with enough conflict and personality drama to keep pushing the story forward. The tension between him making a conscious choice to be good, when his natural instinct is to be bad, and the effect that Princess has on him in suppressing a lot of those urges, makes a character driven story about him much easier to develop.

I do still use plotting and structure to set overarching plot goals, but the finer details of the story are left open for spontaneous creation. For example, I knew I wanted to write the scene where the stalker enters Lloyd’s backyard and attacks Princess by the swimming pool from the start. The identity of the stalker though, was up for debate until this morning when I officially decided who it was. I really enjoyed writing this way. Using structure when I needed it to figure out where I was going and letting the rest unfurl organically was fun and frustrating. There have been several points where I’d painted myself into a corner and didn’t know how to get out. But something always came together in the end - albeit to varying degrees of success and gracefulness. (Ahem… subplot with Lloyd and Sheriff Holbrook, I’m looking at you. That ended up taking so long that I just decided to cut it short. I deleted a bunch of content that would’ve rounded it out, and yes, I do mean deleted as in permanently deleting those chapters from my hard drive/cloud.)

Writing TPATL as a character driven story has enriched my ability to think on my feet, solve plot holes as they crop up, and write characters with richer internal conflicts. Even Princess has become more complex to the point where she’s less of a reader insert and more of a real character. Her behavior is fairly consistent and there’s an identifiable personality with its own unique thought patterns.

I even dove into Lloyd’s childhood with the Idaho subplot. Unfortunately, this had the side effect of turning the story into a massive plot sprawl. I needed to wrap things up and tie off loose ends to get back to the main storyline. In hindsight, had I planned this out architect style, the narrative would have flowed smoother, culminating in a more logical conclusion.

As I approach the climax of TPATL, I’ve found myself grappling with a number of challenges because of my lack of planning. At this point, the whole thing is a maze. It’s irritating, especially for someone averse to revisiting their past work, but it’s forced me to think creatively and find innovative solutions when I’ve written myself into a corner.

So, to answer your question: usually I’m a plotter. My natural inclination is towards plotting, but TPATL has been an exercise in flying by the seat of my pants. I’d say that this current story has been 85% improvised and 15% planned.

#penguin replies#penguin comments#writing process#alice comments#alice rambles#writing stuff#creative writing#how i write#alice talks#TPATL writing process

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Overlook on Pacing

SO, pacing! The element that can break or make your story! :D

As we are talking about writing here, we are talking about the speed of your story: the speed of the events unfolding, AND the speed of how the events are told to the reader. E.g. You can have a story that happens in a thousand years, told in the same number of pages of a story that takes place in ten minutes. The first speed is about pacing the plot, do you rely on exposition to world-build? On dialogue? On descriptions of setting or action? The latter is about the pacing of your prose, how you construct your sentences, where you place—and how frequently—action and dialogue, exposition and inflection.

Plot and structure

First we have to acknowledge pacing is interlinked with genre. Different genres have different conventions due to audience expectations. Pacing both depends and determines the genre. And as one writer might write a space opera today, and a contemporary character study tomorrow, so their pacing would change.

My opinion is that there's no good pacing, only the right pacing--for your story. Want to drag a kiss into two pages long? Do it, but with intention, which comes with due diligence on studying different types of story structure. The most useful writing advice I got on this is Ursula K. Le Guin's two-word wisdom:

Crowd, Leap; which event serves best in lengthy detail, which can and should be a sweeping impression. This requires some planning ahead of time, so all-panster might feel a bit 😬 here. I will put a post together on panster-planster-planner later. For now, I say for panster, write all the scenes the way they are coming to you right now, as much and as quickly as you can. You can sort the event pacing in editing.

A recommendation you might have heard ad nauseam: Blake Snyder's Save the Cat beat sheet. Like any plot structure studies, take a look, apply it to the story you love, see how they worked or not worked, and take notes on how that might serve your own writing.

Save the Cat Beat Sheet Template • Infographic

Stories exist with a paradoxical preposition: what we read is past tense by the nature of writing and reading, yet many, especially genre fiction writers, strive to provide the sense that the unfolding of events occurs in front of the reader's eyes; there, the sense of wonder, suspense, or urgency. Even with in flashback of The Bad Thing Hundred Winters Ago, the story moves forward because we get a clue of why something is happening/going to happen now or why/how the characters are the way they are, etc..

(Note I did not say "plot," only "story." Because Story is more than just what happened, but how what happened and where what happened and why what happened.)

Everything you put on the page should be thoughtfully curated. Every scene and each word has your own reason for why it's exactly where it is—a process that takes time and practice and critique, but trust that it'll come:)

This leads to the other part of pacing: controlling the flow, thus (attempting to) control how your readers think and feel about the story.

Save the Cat! website has many beat sheet analysis of popular movies that can be helpful in understanding how to apply the principles.

Musicality

Stories work in forward motion, pulling readers along with them. Sometimes the motion is fast, action-packed and no breathing room, like what the story character is experiencing; sometimes the motion is slow, maybe to mimic a sense of conversational tone, writer to reader, or to create the agony of suspense.

The gradations of these motions are no accidents: again, intention. Be aware of how your placement of descriptive writing, dialogue, beats, the rhythm of your sentences might change the reader's perception of time. And rhythm is in every word in every language (multi-lingo people, like yours truly, might notice how this affect the way you like your sentence constructed and use it to create a style true to you).

In short, longer words/sentences/paragraphs=slowing down. shorter words/sentences/paragraphs=speed up. There should be a balanced combination of acceleration and deceleration. Usually this is combined with story beats (action scene is followed with reaction scene, give the readers breathing room and create anticipation for next action).

An advice to combat writer's block I got when I first started writing was "Read poetry out loud."

Read anything out loud. Books from writers you like, song lyrics, your own writing. Get a feel of the shape of how the words are put together. This great advice does have an obvious deficit, ofc, in requiring the advisee possessing hearing and speech ability (and a deeper connection to them both; some people are just more visual, then it can be the length of sentences and paragraph on paper that matters). Anyone here who are writing hearing-impaired would like to chime in, we would be very grateful.

#writing#writing advice#fiction writing#speculative fiction#creative writing#writers of tumblr#resources for writers#writing resources#writer community#writing stuff#writing inspiration#koda writing advice#writeblr#motivation#quotes

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

What makes a great story?

If your aim is to take writing from hobby to profession, you have no doubt asked yourself “what makes a great story?” What is it that takes a story from enjoyable little diversion to a truly great read?

Human beings are creatures of pattern. In fact, pattern recognition is one of the things that defines our humanity. So, it only makes sense that successful stories will have some similarities in what makes them successful.

When I think about what makes a great story, my mind flits to classic archetypes, memorable characters, and relatable plot points — even if we’re talking about sci fi and fantasy. Lord of the Rings? Middle Earth may not be real, but the enduring bond between Frodo and Sam is something that affects us on a human level.

Today I’ve gathered together what readers and writers collectively think makes a story great.

5 Elements of a Great Story

1. Setting

I already mentioned Lord of the Rings so let’s continue with that, shall we? Tolkien is known for his detail and depth in every aspect of storytelling, including setting. I’d argue that The Shire itself is just as much of a character as the hobbits that exist within it.

Immersion is incredibly important in any novel — you want to draw your reader in and convince them to stay; and while a relatable character can do this, our egos can draw us even more to a place that we can picture ourselves in while reading.

So, rather than shoot of a quick“Sarah arrived home, exhausted, and immediately went to bed”, try something more along the lines of:The usually-easy walk up two flights of carpeted steps to her apartment door was exhausting. Upon opening the flimsy portal, she turned the multiple locks within to keep out unsavory elements of her neighbourhood and turned to face her surroundings: dimly lit and simplistic, the building had been built in the 1970s and was by no means her dream space to live. Still, it was home. She crossed the linoleum-tiled entryway making a beeline for her bedroom and collapsed on the unmade bed, immediately falling into a fitful slumber.

Point out elements of Sarah’s surroundings tell you a bit about Sarah herself too. Never avoid a good chance to characterize your settings!

2. Character

Why is the Harry Potter series so successful? There are many elements. Timing allowed a generation to grow up as the characters in the book did, the school houses created a feeling of team loyalty among readers, but most importantly, the archetypes of its characters gave everyone reading someone to relate to. But how do you create a relatable character?

In Jungian psychology, archetypes define a collectively inherited unconscious idea, pattern or thought, image, etc., universally present in individual psyches. By looking to these, you can avoid the Mary-Sue trap and build relatable characters that your readers can latch onto that are not simply reflections of the writer.

Harry Potter is The Hero. Dumbledore, The Magician. Fred and George — The Jesters. And so on. Character archetypes are the closest a writer can get to a cheat sheet for a winning novel — as long as they know what they’re doing in the other parts of their writing too.

3. Plot

Perhaps this goes without saying, but a good story needs a good plot. But, this is something that is easier said than done. There are a multitude of outline structures that you can find online if you do a bit of searching, but I really love the ‘Save the Cat’ method.

Blake Snyder was an American screenwriter who published the novel ‘Save the Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need’ in 2005. The outline divides a plot into ‘beats’ that can be applied to any genre of writing well beyond the screenplay.

First, divide your story into three acts. From there, divide each act into scenes.

I’m going to be talking to you more about Save the Cat in a future blog but a resource I highly recommend to break down plot in your mind and apply it to your own story is savethecat.com’s listing of Beat Sheets.

4. Theme

No, no, we’re not talking about a fevered elementary school paper about what we want for Christmas (sorry, couldn’t help it). We’re talking about the overarching theme of your novel — the message you want to get across, the meaning that you explore throughout your literary work!

Like with characters and plot, there are patterns when it comes to themes, tried and true options that tend to do the trick in pulling in a reader and helping them to relate to your story. Themes are nearly endless, as you’ll find if you take a spin through this listing, but five that you’ll see time and time again are:

Good vs Evil

Love

Coming of age

Courage and perseverance

Redemption

… I’ll also throw in a bonus, of ‘Revenge’, which can act as the darker side to your Redemption theme.

5. Style

Think about your top three favourite authors. I bet that as each name comes to mind, you also get a feeling about them, reflective of their works. My feeling for Chuck Palahniuk is very different from my feeling for Audrey Niffenegger. A comparison between the two could perhaps be described as sharp vs soft.

As a writer, you want to find your style. A writer’s style is their voice, so of all areas this is the hardest to advise on. But some tips I would suggest for bringing your own voice out would be:

Write in the point of view that feels right to you. Don’t let anything else influence this. If you are using a comfortable POV, your voice will have more room to grow.

Meditate on your prevalent internal moods. Are you by nature a positive person? Let that shine through. Are you anxious? Don’t hide that — allow it to colour your work.

Has a particular writer inspired your own writing journey? Start off by paying homage to them. An artist learns by tracing and copying — a writer can do the same. Eventually your own voice will make its way out.

Identify why you write. Is it just for fun? Is it for commercial purposes? Is it to get a deeper message across? The gravity or lack thereof should be felt in your words.

Ernest Hemingway once said: “There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.”

This applies very much to finding your voice. Don’t hide any part of yourself — let it come through in your writing and you’ll have cemented your style.

Prep your story formula and get writing!

I hope that this has given you a base from which to work on when crafting your next novel. As creative types I know it can be in our blood to go against the grain, but when it comes to honing your abilities as a writer, there’s nothing wrong with trying out methods that have worked for hundreds of others in the past.

Make them your own, find your voice, and I’m sure you’ll have a winning novel out in the world in no time!

#writing#writing community#creative writing#new author#writing help#writing tips#writing advice#writing resources#writing tips and tricks

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I did some reflection on my writing processes outside of my webnovel one and thought about how like. My earlier college drafts for attempted manuscripts (I say tradpub a lot for this when I basically mean a nice 80-100k manuscript) actually got finished a lot more consistently. Then in later college I had a lot of ideas and a lot of "this WILL be a movie" thoughts but the manuscripts got finished less I feel. Rising Shards drafts started moving towards web novel style, and I steadily have figured out how to be productive in that format since then.

But I still feel like I haven't cracked the manuscript style for a long time and I want to tackle that to grow my creative muscles. Some of my big goals for Project ZERO were to write something with different creative muscles than I use for RS and to make something for tradpub that isn't as precious so I don't get as discouraged when I submit to agents, but for all of 2022 I got very little done on it and I was not happy working on it. I have been thinking about my formats, trying to figure out my processes and what worked and what didn't. For example, my early college drafts went from coming up with characters to just kind of pantser writing through it. Then later college I really just tried to do cinematic and match movie outlines, but that didn't lead to many finished drafts of anything. For ZERO, I've been trying the Blake Snyder beat sheet like I learned in college, but the sparks of ideas have not lasted long enough to come up with much for that story.

Part of those goals are for the challenge of tackling that impossible tradpub mountain, part of it is because I want to grow my skills, and part is probably cynically wanting that big book contract, but when I'm cynical I don't think I write well, and I think that's what slowed ZERO down a great deal.

So a 2023 goal for my writing is to try and get that like manuscript finishing ability in a new way, to figure out a new process for writing that isn't such a drain. If I trudge for another year on ZERO and this fantasy idea and get nowhere on them and am miserable working on them, I'll probably bench the big manuscript ideas for a while. My main focus is still on Rising Shards (I probably don't have to keep saying this but it's kind of a rallying cry since RS is so like me and I'm so happy with it and writing it) but that doesn't mean I can't tinker around with other ideas and forms and processes. That sounds so dorky but I love me some writing processes. 🥰

—Chiral

#writeblr#writers on tumblr#chiral writes#rising shards#writing wip#should I have a tag for specific wips#chiral wip fantasy project#chiral project zero

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The day people realize all good movies follow the Blake Snyder beat sheet in some way is the day the world heals

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

6,18,21 for the ask game :)

-drewtanakaed

Thank you! Love your profile pic :)

6) Do you outline your fics? If so, how?

So I have a couple different processes for this, most of which involve the Save the Cat Beat Sheet by Blake Snyder. However, what's more important to me is each event having a causal relationship, where A leads to B leads to C leads to D. Red Ruse is the project I've done the most outlining for, because my idea for Maven's character arc changed so drastically while I was drafting. I ended up dividing the entire project into four distinct parts: The Girl, The Snake, The Bride, and The Queen, and jotting bullet points for what I needed to happen in each section. I also did a beat sheet for it afterwards which helped me solidify the third act.

18) What's the most obscure thing you've researched for a fic?

What lightning feels like and how the scars look for Lover's Curse. Turns out it's a burning sensation, which probably doesn't translate well in Maven's brain (immune to fire), so I went with a needle description instead. If you don't know what scene I'm talking about, it's, uh, cursed. Very cursed. I dunno how to explain it.

Look, the chapter was titled "A Brand New Day"--

21) Writers choice - pick any of these questions that you want to answer.

Picking:

1) Who is your favorite character to write for and is this the character you find easiest to write for?

Maven, hands down. He's got so many layers and contradictions, and his perspective is so skewed I feel I learn something new each time I portray him. Self indulgent example:

A dagger to her chest as much as mine. My movements grew gentle, tracing her starved frame as though it had curves, as though we were in a happier plane where my love wasn’t poison and hers destruction. She retaliated with lies of her own, bitter ironies I swallowed with frightening ease.

Promise never to cage me. A pinch. Promise never to silence me. A bruise. Promise you’ll always listen, see my dreams as your own, forge a brilliant future with me as your equal.

Never, my dear.

Always, my dear.

Mare is generally the easiest to write, with the exception of Red Ruse. There's a delicate tone to balance there, one I can have difficulty nailing. In that case, Evangeline is a lot easier. Her motivations are clear, her voice is sharp, and Elane is always there to coax out her soft side when I need it.

#red queen#maven calore#maven#mare#mare barrow#red queen fanfiction#red queen fanfic#evangeline samos#evangeline

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Resources Round-Up!

Here are some of the tools and tips we discussed on our 2-part writing episode.

L.C. Mawson's Outlining Process

The Blake Snyder Beat Sheet (is THAT what "The Dean Winchester Beat Sheet" is referencing?!)

Do you have other writing tools or tips you use? Reblog and tell us about it!

0 notes

Text

Incoming Text for Lenny @kodaklens

Hey, Lenny! It's me, Angelo.

This is the blueprint every screenwriter follows to create the story in their screenplay, it's called "Save the Cat beat sheet"

Make sure you follow this blueprint for all your future screenplays that will be produced by Roc Nation.

You can buy the book on Amazon, here is the link: https://www.amazon.com/Save-Last-Book-Screenwriting-Youll/dp/1932907009

Here is a detailed explanation about the concept of save the cat beat sheet:

The Save the Cat beat sheet is a storytelling tool popularized by Blake Snyder in his book "Save the Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting You'll Ever Need." It's a framework designed to help writers structure their stories effectively, particularly in screenwriting but applicable to other forms of storytelling as well, like novels or short stories. The beat sheet is divided into specific "beats," or key moments, that guide the progression of the narrative. Let's break down the concept in detail:

1. Opening Image:

This is the first impression the audience gets of the story world. It sets the tone and often hints at the themes or conflicts to come.

2. Theme Stated:

The theme of the story is introduced in a clear and concise manner. It's usually expressed through dialogue or action.

3. Set-Up:

This section establishes the protagonist's ordinary world, including their daily life, relationships, and goals. It provides context for the character's journey.

4. Catalyst:

The catalyst is the incident or event that disrupts the protagonist's ordinary life and sets the main story in motion. It's the call to adventure.

5. Debate:

After the catalyst, the protagonist often wrestles with whether to pursue the new path presented to them. This beat highlights the internal conflict or hesitation they experience.

6. Break into Two:

This marks the point where the protagonist fully commits to the new direction and enters the special world of the story. It's a clear turning point that propels the narrative forward.

7. B Story:

While the A story focuses on the main plot and the protagonist's external journey, the B story introduces a secondary plotline often related to relationships or personal growth.

8. Fun and Games:

This is the section where the story's premise is explored to its fullest. It's characterized by excitement, adventure, and sometimes humor as the protagonist faces challenges and learns new skills.

9. Midpoint:

The midpoint represents a significant shift in the story. It's a moment of revelation, where the protagonist gains new information, changes direction, or experiences a major setback.

10. Bad Guys Close In:

As the story progresses, obstacles and antagonistic forces become more intense. The protagonist faces mounting pressure and setbacks, increasing the stakes.

11. All Is Lost:

This beat represents the lowest point for the protagonist. They experience a major failure or loss, and it seems like all hope is gone.

12. Dark Night of the Soul:

Following the all-is-lost moment, the protagonist confronts their inner demons and doubts. It's a moment of reflection and self-discovery, leading to a renewed sense of purpose.

13. Break into Three:

The protagonist finds the strength or insight they need to overcome their challenges. They make a final push toward their goal, armed with newfound determination.

14. Finale:

In this climactic sequence, the protagonist faces their ultimate test. They confront the antagonist or main obstacle, leading to a resolution of the story's central conflict.

15. Final Image:

The final image mirrors the opening image but reflects the changes the protagonist has undergone throughout their journey. It provides closure and leaves a lasting impression on the audience.

By following the Save the Cat beat sheet, writers can ensure that their stories have a strong narrative structure, engaging character arcs, and satisfying emotional payoffs. While not every story will adhere strictly to this framework, it serves as a valuable tool for crafting compelling and well-paced narratives.

0 notes

Text

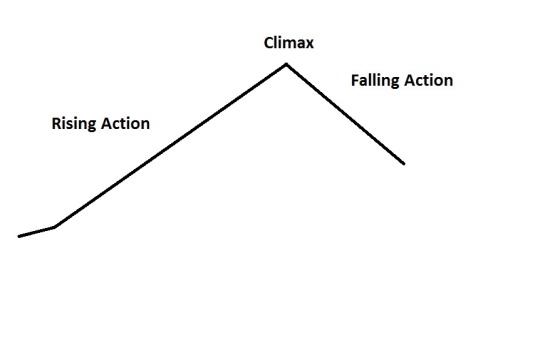

Strong Act Structure Creates Stronger Stories

by @septembercfawkes

In storytelling structure, people use the term “act” rather broadly and vaguely. Most in the writing community break stories down into three acts: beginning, middle, and end. But if you asked many writers what an act actually is, they would probably give you blank stares.

Despite acts being key structural units in stories, they don’t get a lot of attention.

And when they do, they are often treated simply as containers to fill with beats from a beat sheet.

Luckily, the basics of acts aren’t too hard to grasp, if you already know the basics of structure.

And once you grasp acts, your whole story will have not only better structure, but better pacing and better direction.

As mentioned, those who usually give the act any mind, are often following a “beat sheet.” This is a list of key moments (or “beats”) that are supposed to happen in a specific order, and usually, at a specific time, to make a story more satisfying (put simply). Beat sheets can be very helpful and very effective. Two of the most popular are Save the Cat! by Blake Snyder and Vogler’s version of The Hero’s Journey. Another common structural approach is the 7 Point Story Structure.

Often beat sheets will be separated into acts, so if you are familiar with them, you may have some understanding of what’s supposed to happen in each act.

If you aren’t familiar with them, that’s fine too.

Basic Story Structure

I’m going to explain acts from the bottom up–and we’ll get back to the beat sheets for those who like to “beat” out their stories.

It has a rising action, climax, and falling action.

If we zoomed in a little more, there would be an inciting incident. This is the turn in the beginning of the story that kicks off the main plotline–it often appears as an opportunity or a problem for the protagonist.

Charlie Bucket finding a golden ticket.

Peter Parker getting bit by a radioactive spider.

Boo coming into Monstropolis in Monsters Inc.

These are all examples of inciting incidents.

From there, the story escalates, more or less, until it gets to the climax, where the main conflict between the protagonist and antagonist hits a peak and gets resolved. This creates a turn that then leads to the falling action.

That’s basic structure.

Basic Structure and Structural Units

But it’s not only basic structure for a story as a whole, it’s also basic structure for just about any solid structural unit. Ideally, scenes should have this structure, sequences should have this structure, and yes, acts should have this structure.

Each unit fits inside the bigger unit, like a Russian nesting doll, or a fractal.

The difference is that, the smaller the structural unit, the smaller the impact.

So the climax of a single scene will be smaller than the climax of a sequence. (This term isn’t used very often, but a sequence is a string of related scenes, that don’t fill up a whole act.)

The climax of a sequence will be smaller than the climax of an act.

And the climax of an act will be smaller than the climax of the overarching story.

Basic Act Structure

Nonetheless, other than the story as a whole, the act is the biggest structural unit. This means each act should crest into a big turn in the story.

It’s not just that the story has one major peak–a turning point–at the end.

It should have several big peaks along the way.

It should also have several “valleys” along the way.

While the overarching story is escalating in general overall, it still has rises and falls in each act.

Most commonly, people view stories as having three acts.

This means the structure will look somewhat like this:

It’s also equally common to split the middle act in half. Frequently, in the middle of the second act, there is a major turn, called the midpoint (you may have heard of it). If this moment is major, it’s often more helpful to picture the structure with the second act split into two, something like this:

One may arguably call this a four-act story, but to keep with the most commonly used terms, it’s probably better to call these pieces, Act II, Part I & Act II, Part II.

When you look at this structure, you may realize something … there is no saggy middle! There is also no boring beginning, or lackluster end.

This is because there is a rise, peak, and fall within each act (and arguably two in Act II).

Frequently, people divide these act pieces into quarters. Not every writer likes using percentages, but it’s the best and easiest way to indicate when and where something in a story should typically happen–so we’ll use them.

Act I: 0 – 25%

Act II, Part I: 25 – 50%

Act II, Part II: 50 – 75%

Act III: 75% – 100%

Please note that the percentages aren’t laws; they are more like guidelines. But we need the guidelines to even have a proper conversation about acts. Once we understand the guidelines, we can play with variations for different effects, but we need to lay a foundation first to get anywhere.

The beautiful thing about this, though, is that you know you need to hit a peak in each of these quarters.

Now, occasionally, writers will cut some or all of the falling action off the structural unit. This is rare for the overarching story (but it does happen!). It is more common for smaller structural units. So don’t panic if all your units don’t have the “fall” into the valley.

Acts and Structural Pacing

The point is, that you have peaks and valleys.

And it’s helpful to have them in the proper places. Why? Because this is what controls structural pacing.

Pacing is more than word count. In fact, pacing more closely links to structure. When the structure of any given unit is solid, the pacing will almost always be exactly what you need. The exception to this is when you are looking at the lines themselves–that’s when things like word count become more important.

Generally speaking, solid structure = solid pacing.

This is why when you understand acts, you’ll be less likely to have pacing problems in beginnings, middles, or ends (no saggy middles!).

Pacing gets tighter the closer it gets to the peaks, simply because the plot itself is becoming more intense.

Each Act’s Climax

Act I

So, when you are writing the beginning, you know you need to be climbing toward a big turn, which will hit before the middle.

What is this Act I climax?

Well, depending on what approach you are using, people will call it different things. (This is where those of you who are familiar with beat sheets pull yours out.)

In Save the Cat! This is the “Break into Two” beat.

In Vogler’s Hero’s Journey, this is “Crossing the Threshold.”

In 7 Point Story Structure, this is “Plot Point 1” (sometimes alternatively called “Plot Turn 1”).

If you aren’t familiar with any of these terms, that’s fine, but know Act I has a climactic turn.

This climactic turn works by locking the protagonist with the main conflict. It is typically marked by the protagonist’s choice to step forward, through a “Door of No Return” (i.e. Crossing the Threshold) or a “Point of No Return” (i.e. plot point). It’s what “breaks” the story into Act II.

The protagonist definitively chooses to go forward on the journey of the primary plotline. This is then usually followed by a transitional segment, that takes us into the “valley.” … There is a lot more I could go into here, but it’s beyond the scope of this article, so let’s move on.

The falling action is often a reaction segment–where the character is reacting to what just changed at the peak. Once the character has at least some sense of their situation, they usually start “climbing” toward a current goal (rising action).

Act II, Part I

Near the halfway mark of the story, you typically hit a climactic peak again. A big turn. People most frequently call this the “midpoint.” It usually involves the protagonist gaining new, important information that helps him move forward more aggressively, or rather, actively, against the antagonist. But it may be marked by a big victory or failure for him too.

The point is, there is a turning peak.

… which leads to “falling” into a valley …

And again, the falling action is often a reaction segment to whatever big change–revelation or action–just happened.

Act II, Part II

Once the character gets some sense of the situation, you know what she’s going to do? Start the climb toward the current goal. Rising action.

And of course, the climb is never easy. Every climb has conflict and stakes–that’s the only way to escalate the story (in other words climb the rising action).

She hits another major turn.

In Save the Cat! this moment coincides with the “All is Lost” beat.

In Vogler’s Hero’s Journey, it’s “The Ordeal” beat.

And in 7 Point Story Structure, this is (arguably) Plot Point 2 (but there is some ambiguity on how that term gets used in the writing community).

If you don’t know those terms, that’s fine, but just know that this is the major climactic moment of Act II (Part II).

And, most frequently, it leads to the biggest “fall” of the story–a big lully drop to a low, low valley. It’s usually the largest reaction segment of the story.

Well, guess what happens next?

Act III

After the character has taken some time to wallow in his failures, he’ll find his footing and start the last climb–to Act III’s climax, which is (almost) always simultaneously the climax of the whole story.

And that’s the basic structure of the story, through acts.

Acts and Inciting Incidents

Now, if we were to zoom in a bit more, we would likely find that each act also has an “inciting incident”–it’s usually what kicks off the next climb. It’s what gets the character to leave the valley and come up with a plan about what to do next (whether or not the plan plays out as intended).

The most recognizable one in storytelling approaches (other than the first one, in Act I) is Act III’s.

After Act II, Part II’s major lull, usually the protagonist gains something that pulls her out of the lull. If you are following along with your beat sheets …

Save the Cat! calls this “Break into Three.”

Vogler’s Hero’s Journey calls this, “Reward: Seizing the Sword.”

And (this is where the ambiguity creeps back in), this is often lumped in with “Plot Point 2” in 7 Point Story Structure.

But Act II will also usually have its own “inciting incident,” something that gets the character on track for the next climb.

And … if we went much deeper into structure, I’d probably need to fill up a whole book. So, we’ll end there.

Just make sure to mind the peaks and valleys of your acts–your story, agent, editor, and readers will thank you for it. Even if they don’t recognize what you are doing, they feel it.

(And you’ll probably thank yourself for it too!)

17 notes

·

View notes

Link

Still working through “Save the Cat” a little at a time and trying to work through the beats of my new novel, Sesame Swallow and the Secret of the Missing Fucks. The key to National Novel Writing Month is to not think too hard; just keep writing. But it’s not easy. Keep trying too hard. Just write. Just write the next line, the next paragraph, the next page, the next chapter.

0 notes