#but instead they linked with only other mollusks

Text

I can’t believe I have brain worms over a living armor mollusk (from dunmeshi) society. they would most likely be a culture of blacksmiths and mercenaries, and chances are they would communicate via sign language or or maybe telepathy if they somehow learn to utilize magic. but I need to know more. Can they leave the armor? does it have to be metal? how do they eat? I need to know more.

#dungeon meshi#the bugs are back#laios ass post i know#but like its such an interesting concept#maybe they came from a failed experiment to mentally link a person and the mollusks?#so that way the mollusks would enhance the strength of the person inside of the armor#but instead they linked with only other mollusks#so thats how they achieved sentience? kinda like the geth from mass effect?#aaaaaaaa i love them <3333#living armor society my beloved <33333333333333#also shoutout to cryptotheism/the caretaker for the inspiration#i remembered a post of theirs that was kinda along the lines of#‘’ok so a creature that lays acidic eggs in others is fucked up but how would their taxes worm#*work#also read amber skies on ao3 by the caretaker it slaps#havent read emerald seas but i really should

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I recently found out a show I liked is 10 years old now so to not be the oldest thing on this blog I'm talking coelacanths for Wet Beast Wednesday. Coelacanths are rare fish famed for being living fossils. While that term is highly misleading, it is true that coelacanths are among the only remaining lobe-fined fish and were thought to have gone extinct millions of years ago before being rediscovered in modern times.

(image id: a wild coelacanth. It is a large, mostly grey fish with splotches of yellowish scales. Its fins are attached to fleshy lobes. It is seen from the side, facing the top right corner of the picture)

Coelacanth fossils had been known since the 1800s and they were believed to have gone extinct in the late Cretaceous period. That was until December 1938, when a museum curator named Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer was informed of an unusual specimen that had been pulled in by local fishermen. After being unable to identify the fish, she contacted a friend, ichthyologist J. L. B. Smith, who told her to preserve the specimen until he could examine it. Upon examining it early next year, he realized it was indeed a coelacanth, confirming that they had survived, undetected, for 66 million years. Note that fishermen living in coelacanth territory were already aware of the fish before they were formally described by science. Coelacanths are among the most famous examples of a lazarus taxon. This term, in the context of ecology and conservation, means a species or population that is believed to have gone extinct but is later discovered to still be alive. While coelacanths are among the oldest living lazarus taxa, they aren't the oldest. They are beaten out by a genus of fly (100 million years old) and a type of mollusk (over 300 million years old).

(image: a coelacanth fossil. It is a dark brown imprint of a coelacanth on white rock. Its skeleton is visible in the imprint)

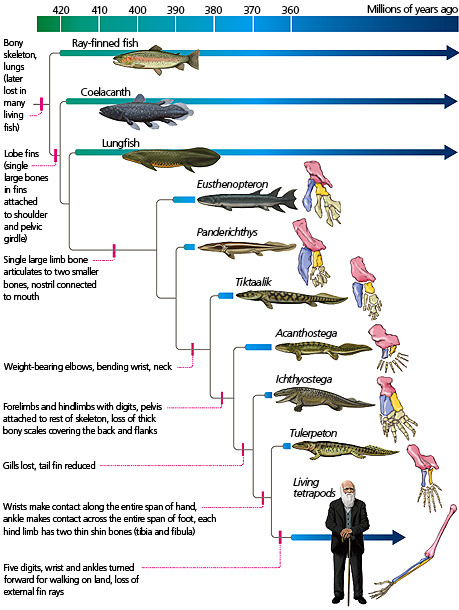

Coelacanths are one of only two surviving groups of lobe-finned fish along with the lungfishes. Lobe-finned fish are bony fish notable for their fins being attached to muscular lobes. By contrast, ray-finned fish (AKA pretty much every fish you've ever heard of that isn't a shark) have their fins attached directly to the body. That may not sound like a big difference, but it actually is. The lobes of lobe-finned fish eventually evolved into the first vertebrate limbs. That makes lobe-finned fish the ancestors of all reptiles, amphibians, and mammals, including you. In fact, you are more closely related to a coelacanth than a coelacanth is to a tuna. Coelacanths were thought to be the closest living link to tetrapods, but genetic testing has shown that lungfish are actually closer to the ancestor of tetrapods.

(image id: a scientific diagram depicting the taxonomic relationships of early lobe-finned fish showing their evolution to proto-tetrapods like Tiktaalik and Ichthyostega, to true tetrapods. Source)

There are two known living coelacanth species: the west Indian ocean coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae) and the Indonesian coelacanth (L. menadoensis). Both are very large fish, capable of exceeding 2 m (6.6 ft) in length and 90 kg (200 lbs). Their wikipedia page describes them as "plump", which seems a little judgmental to me. Their tails are unique, consisting of two lobes above and below the end of the tail, which has its own fin. Their scales are very hard and thick, acting like armor. The mouth is small, but a hinge in its skull, not found in any other animal, allows the mouth to open extremely wide for its size. In addition, they lack a maxilla (upper jawbone), instead using specialized tissue in its place. They lack backbones, instead having an oil-filled notochord that serve the same function. The presence of a notochord is the key characteristic of being a chordate, but most vertebrates only have one in embryo, after which it is replaced by a backbone. Instead of a swim bladder, coelacanths have a vestigial lung filled with fatty tissue that serves the same purpose. In addition to the lung, another fatty organ also helps control buoyancy. The fatty organ is large enough that it forced the kidneys to move backwards and fuse into one organ. Coelacanths have tiny brains. Only about 15% of the skull cavity is filled by the brain, the rest is filled with fat.

(image id: a coalacanth. It is similar to the one on the above image, but this one is blue in color and the head is seen more clearly, showing an open mouth and large eye)

One of the reasons it took so long for coelacanths to be rediscovered is their habitat. They prefer to live in deeper waters in the twilight zone, between 150 and 250 meters deep. They are also nocturnal and spend the day either in underwater caves or swimming down into deeper water. They typically stay in deeper water or caves during the day as colder water keeps their metabolism low and conserves energy. While they do not appear to be social animals, coelacanths are tolerant of each other's presence and the caves they stay in may be packed to the brim during the day. Coelacanths are all about conserving energy even when looking for food. They are drift feeders, moving slowly with the currents and eating whatever they come across. Their diet primarily consists of fish and squid. Not much is known about how they catch their prey, but they are capable of rapid bursts of speed that may be used to catch prey and is definitely used to escape predators. They are believed to be capable of electroreception, which is likely used to locate prey and avoid obstacles. Coelacanths swim differently than other fish. They use their lobe fins like limbs to stabilize their movements as they drift. This means that while coelacanths are slow, they are very maneuverable. Some have even been seen swimming upside-down or with their heads pointed down.

(image: an underwater cave wilt multiple coelacanths residing in it. 5 are clearly visible, with the fins of others showing from offscreen)

Coelacanths are a vary race example of bony fish that give live birth. They are ovoviviparous, meaning the egg is retained and hatches inside the mother. Gestation can take between 2 and 5 years (estimates differ) and multiple offspring are born at a time. It is possible that females may only mate with a single male at a time, though this is not confirmed. Coelacanths can live over 100 years and do not reach full maturity until age 55. This very slow reproduction and maturation rate likely contributes to the rarity of the fish.

(image: a juvenile coelacanth. Its body shape is the same as those of adults, but with proportionately larger fins. There are green laser beams shining on it. These are used by submersibles to calculate the size of animals and objects)

Coelacanths are often described as living fossils. This term refers to species that are still similar to their ancient ancestors. The term is losing favor amongst biologists due to how misleading it can be. The term os often understood to mean that modern species are exactly the same as ancient ones. This is not the case. Living coelacanth are now known to be different than those who existed during the Cretaceous, let alone the older fossil species. Living fossils often live in very stable environments that result in low selective pressure, but they are still evolving, just slower.

(image: a coelacanth swimming next to a SCUBA diver)

Because of the rarity of coelacanths, it's hard to figure out what conservation needs they have. The IUCN currently classifies the west Indian ocean coelacanth as critically endangered (with an estimated population of less than 500) and the Indonesian coelacanth as vulnerable. Their main threat is bycatch, when they are caught in nets intended for other species. They aren't fished commercially as their meat is very unappetizing, but getting caught in nets is still very dangerous and their slow reproduction and maturation means that it is long and difficult to replace population losses. There is an international organization, the Coelacanth Conservation Council, dedicated to coelacanth conservation and preservation.

(image: a coelacanth facing the camera. The shape of its mouth makes it look as though it is smiling)

#wet beast wednesday#coelacanth#marine biology#biology#zoology#ecology#animal facts#fish#fishblr#old man fish#lobe-finned fish#sarcopterygii

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Oviraptor is an extinct genus of oviraptorid dinosaur that lived throughout what is now Mongolia during the Campanian and Maastrichtian Stages of the Cretaceous period some 78 to 70 M.Y.A. The first remains of Oviraptor consisting of a mostly complete skeleton with a badly crushed skull which was found lying over a nest of approximately 15 eggs were unearthed from reddish sandstones of the Late Cretaceous Djadokhta Formation of Mongolia in 1923 by a North American paleontology expedition led by Roy Chapman Andrews. This specimen would be formally named and described a year later by Henry Fairfield Osborn in 1924. Because the skull of the specimen was separated from the eggs by only 10 cm of sediment Osborn interpreted Oviraptor as a dinosaur with egg-eating habits, naming the animal Oviraptor which is Latin for "egg seizer" or "egg thief”. The specific name, philoceratops, is intended as "fondness for ceratopsian eggs" which is also given as a result of the initial thought of the nest pertaining to Protoceratops or another ceratopsian. However in the 1990s, the discovery of numerous additional specimens including nesting and nestling oviraptor specimens proved that the initial specimen wasn’t an oviraptor stealing the eggs of another dinosaur, but instead it was a mother oviraptor trying to protect her own nest from a sandstorm. Reaching around 5-6ft in length, 2.5 to 3.5ft tall, and 70-90lbs in weight, oviraptor was a bipedal creature which sported a short, curved, toothless beak and prominent head crest. It had a covering of feathers over its entire body and a pygostyle: several fused vertebrae at the base of the tail that in modern birds is used as a support for tail feathers. With the egg stealing idea now debunked it is believed oviraptor had a much more diverse omnivorous diet comprised of leaves, berries, fruit, nuts, seeds, mollusks, worms, small vertebrates, insects, crustaceans, and other arthropods.

Art work links:

https://twitter.com/Cynderen/status/1486132223833260038/photo/1

http://novataxa.blogspot.com/2020/12/oviraptorosaur.html

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/564920347004490660/

https://nathan-e-rogers.tumblr.com/post/648194189622935552/oviraptorid-adult-and-chicks-late-cretaceous

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rain: Ezra X F!Reader w/Cee

A/N: Prickle ‘verse. Takes place after Prickle but before Clean Dirt. Can be read as a one shot. Reader is established crew with Ezra and Cee. This was written for @autumnleaves1991-blog ‘s Writer Wednesday. I am woefully behind. I legit don’t understand how some of you write fics so fast!

Warnings: Mentions of war, a little bit of angst, but mostly gentle fluff. Feelings.

"Hey, Ez," Ezra is engrossed in grading the latest haul, testing for clarity and hardness. The surface of CJ's World is cut through with oxbow rivers, fantastic hoodoos of striated sandstone slashed with valleys deeper than any found in Sol system. You're digging for fossils. These rusty carved out plateaus were once the bed of an ancient ocean. Through some trickery of mineralization and chemistry the fossils of CJ's world shine like the fire opals of Old Terra. Big or small, they all have value.

"Ezra," says Cee, "She's doing it again."

"Doing what, birdie?" Ezra takes off the loupe and rubs at his eyes. Rain pelts on the tent, even sheltered the humidity soaks through.

"Look." Ezra draws open the tent flap and sees you, standing in the rain, your head tilted up, no gentle shower this, rain that pelts down hard, turns the view across the sharp-cut canyons to silver curtains. Your clothes are plastered to you like a second skin. The rain actually aids your cause, washing away loose sediment, making the fossils easier to get to. You bow your head and let the stinging rain hit the back of your neck, let it fall on your closed eyes, your outspread arms. You laugh at the sky.

"What do you know about Falnost?" Cee's eyes go distant for a beat. She has a memory to rival Central computers.

"Hmmm..about two thirds standard grav, class C5, would've rated lower if not for it's primary. Dustball."

"Mmm-hmm."

"She's not used to real weather," says Cee.

"Observant as ever," says Ezra. The rain is not gentle. It is chilly and hits your skin like handfuls of flung sand, but is so different from anything you've known, so new that you can't help but stand there with a huge, dumb grin plastered on your face, even as your teeth chatter with the cold. Ezra comes and gets you.

"C'mon, Artichoke, while the rain does feel slinky and delicious it is not worth hypothermia."

"Sorry, Ez," you say and allow him to take your hand and lead you back to shelter. This has become something of a habit. Many worlds in the fringe are dustballs like the one you fled, algae and fungus growing on every bit of pipe that condensation beads on. On Falnost they had a deal with the ice-miners, discounted accommodations on world or on station in exchange for chunks of ice from your primary's lush rings de-orbited, burning and evaporating as they fell. The idea was that, eventually, there would be moisture enough in the atmosphere to trigger rains. Someday Falnost will have an ocean, but you won't be there for it, half your life spent harvesting rills of water from sail-traps, careful irrigation channels covered over with plastic sheeting, calorie vs water consumption ratios discussed every planting season. How many credits do we net vs wha† we have to spend? You got fucking sick of dreaming of an ocean your great grandchildren might paddle in. You skimmed enough to buy your way off world and since then you have seen things that you never would have believed as a child.

The first time you heard thunder was on a world called Ingwy. Your first thought was artillery. Ingwy was a contested world, Karoclan and Lussia Collective skirmishing over land rights, while small stakes droppers like you and Ez and Cee swooped in to reap the spoils while the big corps and clans fought each other. It was the middle of the night and you were on your feet instantly, railgun in hand, screaming that there was incoming, to take cover. Someone had flicked on a utility light hanging from a cord that swung, illuminating the inside of the tent in sickening arcs, and there's another explosion, this one so loud you feel the pressure change in your ears, hear your own voice crying out in tandem, white hot light even through the thick weave of the tent.

"It's just thunder," Ezra yells over the sound of rain slamming against the tent.

"That was an explosion!" He presses gently on your arm until you lower the rails.

"It's just loud," says Ezra, "It can't hurt us. We're safe here. Put the gun down." You set on the edge of your cot and put your face in your hands.

"Kevva. You must think I'm the dumbest dirt-farmer this side of the Great Arm." The cot dips as Ezra sits beside you.

"Not at all," he says, squeezes your shoulder, "I come from a backwater as well. First time I ever saw a proper ocean I nearly lost my breakfast right there on the beach." Thunder peals again and you flinch, shrink against him slightly.

"Static electricity," says Ezra, "That's all it is. Builds up in the clouds and discharges into the ground." He keeps his hand on you as he speaks, fingers gently squeezing the juncture of your neck and shoulder, "The sound you hear is the air in the path of the lightning instantly heating and expanding. It makes a sonic shock wave, like any explosion."

"Like the boom when ships lift," you say.

"Just like that, Artichoke," he says, "Storm's already moving off, see?" The rain pelting the tent has settled into a steady drone. Thunder grumbles, a low, almost soft sound, not the air-rending explosion that shocked you out of sleep.

"We should try to rest," says Ezra, gives your shoulder one more firm squeeze and a little shake, and when you look up, he's smiling, dimple just beginning to sink into his cheek.

"Yeah," you say, "Okay." He kills the utility light and settles into his cot. You can hear the music from Cee's headphones, the tinny, fast pop she favors, threaded through the white noise of the falling rain. She slept through the whole thing.

The ancient life of CJ's world favored heptagonal symmetry, long-dead mollusks like seven-sided shields shine out of the rusty ground, the smallest the size of a fingernail, the largest the size of dinner plates. This is a good deposit. The small ones are fashioned into jewelry and buttons.

"They take these great big ones and slice them micron thin," says Ezra, "Use them for window-glass in the temples of the Ephrate. They say it is like standing inside Kevva's very beating heart."

"I can see why," says Cee, and so do you. The minerals that limn the shells shine translucent red with brilliant streaks of orange, yellow and even thin threads of green and blue.

"They say that Kevva's first heart-beat ignited the explosion that became the universe," says Ezra.

"You really believe that?" Asks Cee.

"I don't know if believe is the right word," says Ezra, "We all grew up with these stories, why my grandmother..." You smile and tune him out. The back and forth banter between Cee and Ezra is a pulse that underlies every harvest. Cee has grown more talkative with each drop. Their relationship has a growing ease to it. You don't know exactly what happened between them before you joined up, but Cee's initial skittishness and Ezra's new healed scars tell a story you can guess the shape of. You let their conversation fade into the background, focus on the work of your hands, the meticulous scrape of soft sediment away from the hard glitter of the fossil, working around the seven sided edge, loosen enough up to get your fingers under the shell and you can pry it out, focus on the sounds of the world around you, no birds on CJ's world, but there is a range of bug-music, hidden in crevasses in the midday heat, all metallic clicks and creaks. Your rail-gun rests within easy reach, as always. You worm your fingers under the edge of the shell, wiggling it like a loose tooth, pops out of the sediment suddenly and you plop on your ass in the sandy dirt.

"You all right there, Artichoke?" Ezra grins at you.

"I'll recover." You dust yourself off and take your prize over to the tub that sits in the shadow of the pod. Further cleaning and grading can be done after dark. Nights are long at this latitude. You stretch in the sunlight. This job is a milk-run compared to other drops, but hunkering in the dirt still hurts your knees and you feel every bit of it when you stand. There's a familiar sound, like a rumbling stomach, thunder, you think and glance up.

"Ezra!" Your voice is urgent and sharp and he's scrabbling up in a heartbeat, hand on the thrower at his hip, but when he stands there is only you pointing out across the vast expanse of sharp-carved valleys and hoodoos, lined in sharply delineated shadows and rusted cliffs where the light catches. The rainbow swoops skyward into grey cloud-bellies, a luminous curtain against the grey clouds, distant rain falling across the canyons.

"Ezra, look!" Ezra exhales, tension leaching out of his shoulders. His hand drops away from the thrower.

"Oh, hey, a rainbow," says Cee. You lower your arm and just stare, transfixed at the glowing phantasm, brightening and dimming with the movement of clouds between it and the sun.

"It's beautiful," says Ezra. But he's not looking at the rainbow. He's looking at you. Your eyes are wide, lit up with wonder, an unconscious smile creeping across your face, crinkling the corners of your eyes. The stiff professionalism that you wear as close as your body armor momentarily set down, forgotten. Ezra's heart squeezes. There you are, he thinks. He can count on his one hand the number of times he's seen you smile like this, open and carefree, rare and precious as the gems the three of you pull from the ground. Part of him wants to kiss you, but he suspects he would end up on his back in the dust with the barrel of your railgun jammed beneath his sternum, so instead he brushes his hand against yours and your fingers find his and squeeze hard.

"I've never seen one before," you say, barely aware of Ezra's hand linked with yours, "I mean, I know what a rainbow is, but I've never seen one. Not in the real, just in vids."

"They don't have rainbows on Falnost?" Says Cee.

"They don't have rain on Falnost," you say, "Get's a little hazy sometimes after the ice-haulers make a drop, but that's about it." You shake your head as if just waking, the rainbow still shimmers, a bit duller now, and you are suddenly aware of Ezra's hand clasped with yours, the gentle pressure of his grasp.

"Sorry," you drop your eyes, "I got distracted. We got work to do." Ezra gives your hand a squeeze and then lets you go.

"Not to worry, Artichoke, rainbows are fleeting things. You look your fill while you can." And so you do. So does he.

#writers wednesday#ezra x reader#ezra x f!reader#ezra prospect x f!reader#ezra (prospect) x f!reader#ezra and cee

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mermay day 3: Bizarre And Cool Variations

If you’ve ever thought to yourself “is there more than just fish mermaids? Are there different kinds of fish mermaids?” Well theb congratulations. You prove that people have always been people, because we’ve been coming up with different varieties of merpeople since at least 400 BCE.

From what I can tell, Greece was the first to make more interesting variations. They created the Telchines and Ichthyocentaurs. Telchines have several descriptions but among them are dog like and mermaid like hybrids. It was said they had the heads of dogs and tails like a fish. Sometimes both and sometimes only one. They were said to know magic and were eventually cursed by the gods for using foul and evil magic. Ichthyocentaurs are so interesting to me because they are centars with a fish tail instead of hindlegs or tritons with two horse legs on their tail.

Ichthyocentaurs spawned several other similar looking mermen designs including tritons with clawed forefins on their tails, wings, and in roman times lobster and crab claws on their tails. This then spawned a crayfish triton and sonewhere in between we get two tailed tritons and tritonesses.

Inuit cultures in the far north of Canada and Greenland had a sea goddess named Sedna. Who by some accounts had a seal, orca, or whale tail. It’s hard to pinpoint when belief in Sedna began and exactly when Sedna developed mermaid iconography but she has always been closely linked with sea mammals and sea life.

In Chilé tales of the Millalobo and his merchildren who had sea lion tails were prevalent. Said to be gods and had golden hair. Pincoy was Millalobos son and his sister wife Sirena Chilota who had golden scales not too dissimilar from Suvanamaccha who was a golden tailed mermaid.

The yawkyawk of Aboriginal myth was said to have seaweed for hair. A similar aesthetic to tritons who were often described with blue skin and green hair.

One of my personal favorites is the Sazae Oni who could shapeshift into a human form. And in its demon form it had the lower half of a mollusk. Making it a very rare mermaid like creature with a shelled lower half. It has a rather wellknown story of stealing pirates balls in exchange for gold. It was also known to travel to inns and devour the innkeeper at night.

Avatea from cook islands myth was half fish on the left side as opposed to from the waist down.

Interestingly enough there doesn’t seem to be any octopus hybrids in mythology. You could maybe argue Scylla was the first tentacled hybrid but she wasn’t really depicted as half octopus and was more similar to the hydra or a dragon. Cecaelian creatures seem to be a unique creation of Disney’s little mermaid.

#mermay 2021#mermay#mermaids#mermen#mermaid#Ichthyocentaurs#tritons#triton#Telchines#picoy#millalobo#sirena chilota#sazae oni#sedna#yawkyawk#cecaelia#the little mermaid#greek mythology#japanese mythology#chilean mythology#aboriginal mythology#inuit mythology

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

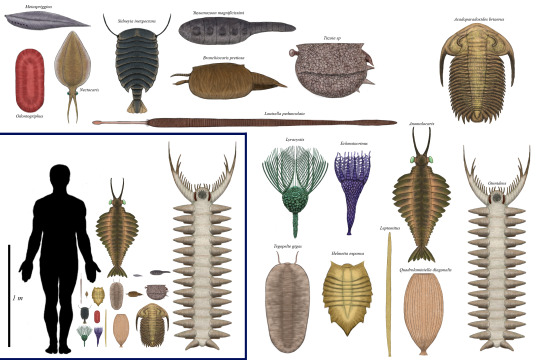

As many know well the Cambrian is the beginning of our world’s biodiversity, is an advance follow up of the ediacaran flourish of life under the ocean, the major period of life diversification with the explosion and rise of the many major clades of animals that would establish for the next 500 million years, such as mollusks, annelids, arthropods, chordates, etc. as well alongside them some other very bizarre clades that arose and at the same time perished in that span which couldn’t leave any descendant after. The marine life grew up and became more from the pacific sessile or slow filter feeders or detritivorous ediacarans stuck in the sand, radiating into a crazy mosaic of different creatures nothing like anything that appeared before and establishing the bases for the dominant clades today, with different shapes, number of legs, numbers and shape of eyes, segments, and most important… in different sizes, mostly small, but some larger than the average…

For this chart I wanted to do something more than just pick the few largest animals of period which excess the meter long (which could have been just 2 specie), so I tried to see specimen size from all other clades known from the period, giving more variety of what some of the biggest animals were, even if they weren’t gigantic like most of actual fauna, of course with this I have to be a bit selective as not many clades really became enough large, at least in this chart the species I will expose are larger than 10 cm and noticeable enough, so even the largest animals of some clades here will be out for being very, very small…

The world in this point was pretty much the world of the Panarthropods, the major clade that includes all known Arthropoda and stem-arthropod, and there is no doubt that the Lobopodians were one of the major faunistic Panarthropods in many pelagic and benthonic niches, becoming some species iconic for its many bizarre forms and some others for their extraordinary sized, specially the Anomalocarids such as the iconic genus Anomalocaris with known specimens reaching lengths of around 60 cm to a meter long making it one of the biggest predators of the ocean at the period and being the first apex predator of history; there is also a tentative competitor for the position as the biggest lobopodians, as well the biggest animal of the period, the species Omnidens amplus (originally classified as a worm), only know by a preserved set of mouthparts, which scaled up with some relatives like the benthonic dweller Pambdelurion gives a size estimation of 1.5 to 2 meters long, but for the lack of a complete body makes difficult a properly size estimation.

Alongside the Lobopodians were also the myriad species of Arthropods, most of them were in the genesis of the clades that could come up millions of years after, just like Crustaceans, Chelicerata or Mandibulata, but in this point on time these weren’t yet a thing like they would be in next periods, instead the diversity of these was formed by other clades, specially a lot of stem-group outside euarthropods and still unknown to link clades as well others euarthropods unrelated to the major clades mentioned first; the pelagic Tuzoiid Tuzoia sp. was able to reach 18 cm long, the benthonic Sidneyia inexpectans with specimens reaching up 16 cm long and the genus Branchiocaris pretiosa which reached up sizes around 15 cm long, not giants but still pretty large among their groups.

The Trilobites are one if not the major clade of arthropods for excellence during the Paleozoic, with different variety of species, being the Cambrian the pinnacle of its population clades with more than 60 families, most of these were around the lengths of less than 10 cm and often were the prey of bigger animals, but in some others places they were able to reach a very extraordinary size, being one of the biggest species known the redlichiide Acadoparadoxides briaerus from morocco, with specimens reaching up 45 cm long. Apart of trilobites, there were some other relatives which belongs to a major clade known as “Trilobitomorpha” which resemble them in certain anatomical features, but they weren’t true trilobites, such as the Helmetiid Helmetia expansa, a very large soft-bodied looking arthropod of around 27 cm long is one of the largest non-anomalocarids arthropods of burgers shell, and the Tegopeltidae Tegopelte gigas with a size of 19 cm.

The Archaeopriapulida (stem-priapulids) were other of the predatory benthonic animals of the Cambrian landscape, pretty much found burrowing in the sand and mud and protruding from their places, exposing a large proboscis they were mostly ambush hunters. The most well known is probably Ottoia for the common of its specimens, but these often doesn’t pass the length of 8 to 15 cm, but others were bigger that this one, a good example is the species Louisella pedunculata, which the largest specimen reached a size of 30 cm long with the proboscis extended.

One odd group among the Cambrian biota was the Vetulicolians, an enigmatic clade probably related to deuterostomes. These were weird arthropod-looking creatures that shown adaptations for pelagic lifestyle and mostly being filter feeders, many of these tended to be average lengths less than 10 cm, but Yuyuanozoon magnificissimi from comes to be the largest species known, with a length of 20.2 cm

The Chordates diversity during the Cambrian was formed by a small group of vermin agnatha forms, mostly swimming filter feeding of small size of few centimeters, the largest of these was Metaspriggina with specimens reaching up to 10 cm long which wasn’t that large size compared to many Cambrian lifeforms, was still an outstanding length compared to other of the chordates of the period.

Echinoderms were in their early genesis of its diversification with some unique morphology, so bizarre and alien compared to our actual species, as well there were others similar or very close in many aspect to actual ones, although most were very minuscule, some of the few macroscopic forms included, Lyracystis which is the largest eocrinoid with specimens reaching up sizes to 21 cm tall being half of it the arms.

Lophotrochozoa flourished during this period, evolving into the important clades including the very common brachiopods, the basic annelids and the Mollusks, although there were some species that could be classified as the last ancestors or stem-relatives of such clades, they don’t belong to these clades but they are coming to the roots of these, including Odontogriphus which specimens were able to reach up sizes around 12 cm long. Mollusks started their slow path into diversification with early small shelled varieties, most of them minuscule and don’t reaching up few centimeters of length, although few reached some considerable size for the average, such as the pelagic Nectocaris pteryx, the enigmatic cephalopod-like mollusk (?) with specimens reaching up sizes of 7 cm long.

Cnidaria are among the oldest animals on earth which during the cambrian expanded though the warm oceans either as jellyfish or small coral-like forms that could spread in the next periods, among some of these early species there was Echmatocrinus which is a pretty robust form with a height of 18 cm tall.

Sponges were one of the major reef builders of the Cambrian, forming alongside other sessile lifeforms extensive biomes which thrived in the warm swallow oceans. Some of the biggest sponges found so far belong to the species Quadrolaminiella diagonalis which were barrel shaped sponge from the Chengjiang Fauna, with a height of 20 cm and a diameter of around 12 cm. Another species was Leptomitus, a very tall but thin kind of sponge from Burgers Shale, with specimens reaching up heights around 36.4 cm, but with a diameter less than a centimeter long.

A minor stuff worth to mention, other of the bizarre benthonic reef builders that dominated the Cambrian seabed were the archaeocyathids, a group formed by small conical shaped forms with some brachiating forms, similar in many ways to sponges except in inner structure, some of these often reached sizes of around 9 to 10 cm tall and some centimeters in diameter, but according to some mentions in websites and papers some were able to reach up even very larger sizes, with giant specimens reaching around 60 cm, but I wasn’t able upon this date to locate these very big forms so I couldn’t add them (either these are exaggerated estimations from fragmentary individuals or actually those were hinted from other fossil sponges)

References

-Briggs, D. E. (1972). Anomalocaris, the largest known Cambrian arthropod. Palaeontology, 22(3), 631-664.

-Vinther, J., Porras, L., Young, F. J., Budd, G. E., & Edgecombe, G. D. (2016). The mouth apparatus of the Cambrian gilled lobopodian Pambdelurion whittingtoni. Palaeontology, 59(6), 841-849.

- Xianguang, H., Bergström, J., & Jie, Y. (2006). Distinguishing anomalocaridids from arthropods and priapulids. Geological Journal, 41(3‐4), 259-269.

-Whittington, H. B. (1985). Tegopelte gigas, a second soft-bodied trilobite from the Burgess Shale, Middle Cambrian, British Columbia. Journal of Paleontology, 1251-1274.

-Bruton, D. L. (1981). The arthropod Sidneyia inexpectans, Middle Cambrian, Burgess Shale, British Columbia. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B, Biological Sciences, 295(1079), 619-653.

-Vannier, J., Caron, J. B., Yuan, J. L., Briggs, D. E., Collins, D., Zhao, Y. L., & Zhu, M. Y. (2007). Tuzoia: morphology and lifestyle of a large bivalved arthropod of the Cambrian seas. Journal of Paleontology, 81(3), 445-471.

- Rudkin, D. M., Young, G. A., Elias, R. J., & Dobrzanski, E. P. (2003). The world's biggest trilobite—Isotelus rex new species from the Upper Ordovician of northern Manitoba, Canada. Journal of Paleontology, 77(1), 99-112.

- Daley, A. C., Antcliffe, J. B., Drage, H. B., & Pates, S. (2018). Early fossil record of Euarthropoda and the Cambrian Explosion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(21), 5323-5331.

- Aria, C., & Caron, J.-B. (2017). Burgess Shale fossils illustrate the origin of the mandibulate body plan. Nature, 545(7652), 89–92.

-Walcott, C. D. (1911). Cambrian Geology and Paleontology II: No. 5--Middle Cambrian Annelids.

-Morris, S. C., & Caron, J. B. (2014). A primitive fish from the Cambrian of North America. Nature, 512(7515), 419.

-Sprinkle, J., & Collins, D. (2006). New eocrinoids from the Burgess Shale, southern British Columbia, Canada, and the Spence Shale, northern Utah, USA. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 43(3), 303-322.

- Sprinkle, J., & Collins, D. (1998). Revision of Echmatocrinus from the middle cambrian burgess shale of British Columbia. Lethaia, 31(4), 269-282.

- Caron, J. B., Scheltema, A., Schander, C., & Rudkin, D. (2006). A soft-bodied mollusc with radula from the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale. Nature, 442(7099), 159.

- Walcott, C. D. (1917). Middle Cambrian Spongiae. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections.

- Legg, D. A., Sutton, M. D., & Edgecombe, G. D. (2013). Arthropod fossil data increase congruence of morphological and molecular phylogenies. Nature communications, 4, 2485.

- Wu, W., Zhu, M., & Steiner, M. (2014). Composition and tiering of the Cambrian sponge communities. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 398, 86-96.

#Paleoart#paleontology#History Size Chart#Cambrian#Burgess Shale#Anomalocaris#Trilobite#Arthropoda#Echinoderms#Lobopodia

141 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey so I'm somewhat new to the Miraculous Ladybug fandom, and was wondering if you could suggest some good fanfics for me? Also I was wondering, I've seen this character called Felix in some of them and I don't know where he came from?

Oh, welcome to the fandom! There's so many fics I wish I could recommend, but I'm on mobile and have no idea how to link things, I'm sorry.

However, I can lead you to several authors here on Tumblr that you can follow that have created many great stories:

@gale-of-the-nomads : I highly recommend their Soulmate Survey AU, which is mostly pure fluff and focuses on reviving the fandom with their love for Adrienette.

@zoe-oneesama : they have an ongoing comic focused on their AU called the Scarlet Lady AU, which focuses on the idea of Chloe Bourgeois having, somehow, gotten thr Ladybug Miraculous instead of Marinette. This AU is what actually got me into the fandom, and they update mostly Wednesdays and Saturdays. Highly recommend.

@nobodyfamousposts : They have several aus as well, but the one I remember most right now would have to be the Dolls AU, where Marinette somehow has creation magic, and every doll she makes somehow comes to life. These dolls see her as their mother, and they love and protect her, especially her little Chaton. Check it out, it's pure fluff.

@ozmav @maribat-archive : they are creating content for a recent AU in which, due to a certain episode in canon that almost everybody in the fandom hates called Chameleon, Marinette is shipped with Damian Wayne after she and her class go on a field trip to Gotham to visit Wayne Enterprises. It is not Adrien, Lila, or the class friendly, but it does explore a sweet dynamic between Marinette and DCs Damian Wayne, or Robin.

@miraculously-quality-content : check out their OctoDad AU, which consists of Original Characters that explore the idea of the heroes having an actual guide in both their civilian and hero lives. With the Octopus Miraculous, the adult hero Mollusk helps the heroes battle both Hawkmoth and the challenges of life. Basically: Mollusk is a cinnamon roll that can kill you if you hurt his kids.

Here are some others that have some great AUs or just some little ficlets that are very entertaining: @lunian @ladybub @mari-cheres @miraculouscontent @miraculous-of-salt

Now, for Felix. I dont really know much either, but I do know some things, not sure if they're right tho: Felix was a character created by Thomas Astruc in the early stages of Miraculous Ladybug, which we call the PV version. It was designed as an Anime, but they later changed the company to ZAG, which designed it as we know it now.

Felix was cold, distant, and almost emotionless. He didnt want to be Chat Noir, but was cursed with bad luck, and became Chat Noir. The only way to get the curse off was to get a kiss from his partner, Ladybug, who definitely does not want to kiss him. The love square is still in effect, but more snubbing from both sides. Felix doesnt want anything to do with Bridgette, the PV Ladybug, and Ladybug doesnt want anything to do with Chat Noir. But he helps her defend Paris, so she "deals" with him. It was never completed, or even expanded on much, but the fandom really liked Felix, since he wasnt "perfect" like Adrien is made out to be.

Now, the fandom loves Felix more on the basis of "what could have been", and some fanfiction writers really took the charcater and adapted him into a more likeable character, especially after the episode Chameleon which, if you've watched it, you can find many fics and headcanons that "fix" this episode under the tag #mlsalt.

Felix also made a comeback in the fandom after someone leaked the episode names for Season 3, and we saw an Episode that revolves around Felix. The reason why is because Astruc himself had said that Felix was never going to show up in Miraculous ever again, as Astruc absolutely hated his character, but seeing an episode revolving around Felix coming up made the fandom question why? Why did Astruc lie? What is he going to do with Felix? Is he going to make Felix look worse? The fandom isnt having it so far, and had started to create content revolving around Felix and his involvement in the class, and his relationship with Marinette.

@miraculous-of-salt really made me like Felix as a love interest to Marinette in her God AU, in which Marinette is Persephone, the Goddess of Life, and Felix is Hades, the God of the Underworld, or Death.

There are so many fanfics and headcanons and ideas, that I really cant tell you how many I have seen. I've literally only been here 1 year, and I've already seen so much. Each episode that comes out helps us to create more content for our fanfictions, and with Lila Rossi reentering the picture this season, most fanfictions have her as the main antagonist, apart from Hawkmoth, as she is now seen as a greater evil.

You can also check out @ao3feed-ladynoir for more ML fanfiction. They almost regularly post new Fanfiction links to AO3, and they cover almost everything.

I hope this helps you in getting into the fandom further, and if anyone else wants to add more writers or fanfictions to check out, please be my guest and reblog with your info. Let's help someone out, shall we?

Oh, also @buggachat Cant believe I almost forget them.

#miraculousladybug#ml salt#ml au#daminette#felinette#adrienette#lukanette#kagaminette#marinette protection squad#dolls au#soulmate survey#soulmate searcher#maribat#fix it#scarlet lady au#scarlet lady comic#ml season 3#octodad au#god au#goddess of life au#felix culpa#ml felix

333 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3

Finding S and Magda is easy after that. The process almost becomes routine, if teaching ASL to a fairytale could ever be considered routine. They pack up, and head out to where Magda’s tag was last pinged. S usually finds them after that.

Zhenya knows that there’s an expiration date on this, that eventually, when her calf is strong enough, Magda will have to swim north to her feeding grounds. She, like other humpback mothers, will barely eat the entire time she’s in tropical waters raising her baby. She needs to get back to the food-rich northern waters or she’ll starve.

Zhenya doesn’t know what Sid will do then, or what Zhenya’s going to do, for that matter. He tries not to think too much about it, or about all the research he’s not doing, the funding that’s steadily running out. One day at a time, he tells himself. No one’s ever had an opportunity like this before. He has to make the most of it.

S’s vocabulary continues to expand. Geno scrambles to keep up, googling language learning theory late into the night, feverishly combing YouTube for ASL instruction videos.

They’re currently working on colors. Geno doesn’t even know how S sees color, but he does learn a lot when he tries to teach S the sign for “blue.”

Word? S asks, pointing at the blue stripe painted around the boat.

Blue, Zhenya tells him.

S points at the water around them.

Blue, Zhenya repeats. S makes a “wow, okay, no” kind of face. He points at the sky.

Blue, Zhenya says again. S rolls his eyes. He starts pointing at blue things and making a different sound for each. So Geno has to teach him a few modifiers before he’s content: “gray,” and “green,” and “light” and “dark.” It makes sense, Zhenya figures. These are the colors that make up the greater part of S’s world.

S remains dissatisfied with the limited human expression of color, but his fascination with humans themselves doesn’t abate. He shows a marked preference for interacting with Geno, but seems to like Letang and Fleury well enough, especially Fleury. Fleury is the one who decides that they can’t keep calling him “S.” He runs a whole gamut of names starting with “s” past him, and S makes faces at them all, until Fleury tries out “Sid.” That one is met with a shrug and a thumbs up, so “Sid” he becomes.

Sid brings them a fish one day, a beautiful yellowfin tuna, easily a meter long. He heaves it onto the dive platform with pride, then pats its glistening, iridescent side.

E, he says. You like.

Zhenya blinks. Yesterday had included a long conversation on food likes and dislikes, Zhenya talking to Sid while Letang scribbled down data on merpeople’s dietary habits and Fleury googled frantically to try and identify the species Sid was talking about.

Zhenya, for reasons he’s not. Thinking. About. feels his face flush a little. “Yes,” he says and signs at the same time. “I like fish.”

This one. Good? Sid asks.

“Very good. Best.”

“Awww, Geno got a present,” Fleury laughs. “What about me, Sid?” Fish for Flower? He asks, using the sign he’s chosen for himself.

You eat fins, head, Sid tells him, smirking. He looks back to Zhenya, smirk softening. He pats the fish again and looks encouragingly at him.

Oh no, Zhenya realizes. He’s waiting for Zhenya to try it. Right here. On the boat. Raw. Zhenya’s a big sushi fan but there’s a difference between a pretty, delicate slice of sashimi and a whole massive fucking fish, lying bleeding at your feet while a hopeful looking merman blinks up at you, waiting for you to tuck in, apparently.

“Give me my dive knife,” he sighs at Fleury, and with some difficulty, manages to hack off a piece of the yellowfin. Sid watches intently as Zhenya takes a bite.

It’s fresher than the best sushi he’s ever eaten, and it’s actually, gory acquisition aside, kind of incredible. “Wow,” he says. “It’s delicious.” He makes the sign for Sid.

Delicious is very good, for food, he tells him.

I’m happy, Sid tells him. Eat more?

And that’s how Zhenya ends up sitting with his feet in the ocean, hacking pieces of raw tuna off its carcass and sharing them with a merman. And eventually Letang and Fleury, once he convinces Sid to share. He grins at nothing in particular, and wonders how this is his life.

The tuna opens the floodgates, apparently. Sid starts bringing him things. One day it’s a smooth, fist-sized cowrie shell, another it’s a enormous living conch. Zhenya thanks him for that one, puts it in a cooler full of seawater, and sets the cumbersome mollusk free once they’re back to the shallows. The handful of pretty calico scallop shells he receives a few days later, he keeps.

Sid kept some for himself as well, and spends an afternoon deftly knotting them into a sort of necklace using strands from one of their ropes that he cajoles Zhenya into giving him.

No shells these north, S tells them, tying the necklace around his neck and looking pleased with himself. His syntax gets a little creative sometimes.

“Very pretty,” Zhenya signs and tells him. At Sid’s confused look he explains. “Pretty is ‘good,’ for your eyes.”

“Beautiful is very pretty,” Letang helpfully supplies. Sid nods, taking it all in.

When Letang and Fleury are occupied with something else, Sid looks at the movement of Zhenya’s hands as he signs and tells him: your words are beautiful.

Zhenya’s heart thuds painfully. “Word?” he says out loud, hands stilling in surprise.

No, Sid says, and reaches out to tap a finger on the back of Zhenya’s hand. These.

“Oh,” Zhenya says out loud, and suddenly he can’t look at Sid, his chest tight and aching. Sid trills softly in concern, until Zhenya looks up at him.

E? You good? He asks. Zhenya can only swallow, and nod.

Sid’s sitting on the dive platform as he often does, and Zhenya’s suddenly aware of how close they are.

Pretty? Sid asks, and Zhenya nearly dies before he sees Sid follow the question with a touch to his new necklace.

Yes, he replies.

Beautiful, Sid says, reaching out to touch the gold chain Zhenya always wears, looking ever so slightly wistful.

Recklessly, Geno unclasps his chain, letting the gold links slither into his palm. Feeling foolish and helpless, he holds it out to Sid.

Sid’s eyes go wide, and he reaches out to take the chain carefully, gaze a little disbelieving. He lets the chain slide through his fingers, and holds it up to watch the sun wink off of it.

“Here,” Zhenya says, his voice rough. He take it, and lays it around Sid’s neck, doing up the clasp in the back. He runs a finger down it, straightening out the kinks. Sid is making a soft hum in his throat, and his eyes are big and dark. He looks down at the chain shining against his skin, and touches it. Zhenya wants to give him a dozen necklaces, drape him in gold, just to see that soft look of wonder in his eyes again.

Sid reaches up and unties the shell necklace from around his neck, and before Zhenya can move, he’s leaning in close to tie it around Zhenya’s. Zhenya can feel the warmth of his skin, can see the kaleidoscope of color in his eyes. A bead of water slides from his drying hair down his cheek, to the corner of his full, perfect lips.

What the hell is Zhenya doing. What the hell is he allowing himself to feel? He should, if he had any integrity or sense, stop this. Shut down...whatever this is. God, Sid’s not even the same species as he is.

Instead he looks at the soft, pleased smile on Sid’s face, and feels powerless to do anything that would chase it away.

Fleury takes a long look at the shells around Zhenya’s neck during their boat ride back to the marina.

“You should be careful, man. It’s like...I don’t know. All these presents he brings you. You don’t know what they mean in his culture. And now you gave him something back. For all you know, that’s like, getting engaged or something.” Zhenya’s cheeks go flame-hot.

“Don’t be stupid,” He tells Fleury, but inside he think that he’s the stupid one here, probably.

***

He dreams of Sid that night. Dreams about running into him on the street, dreams about him walking up to Zhenya with that smile of his. On two legs and two feet. He dreams that he speaks to him in Russian.

“You like me, don’t you?” Dream-Sid says, with an accent so perfect he sounds like he was born a street away from Zhenya. “You like me.”

Dream-Zhenya opens his mouth and tries to say something back, to protest, but all that comes out is a series of trills and clicks, like the sounds real Sid makes.

“Oh,” Dream Sid says, face slowly going terrible and cold.

“I don’t understand you. I don’t know what you’re trying to say.”

#more things in heaven and earth#sidgeno#sidney crosby/evgeni malkin#hockey rpf#dana writes a thing#does the dead fish need tags? let me know

196 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Scallops … one of the sea’s greatest gifts.

Found in saltwater (like the Atlantic Ocean), scallops are bivalved mollusks that live inside a hinged shell and can be found around the world. Unlike oysters, mussels, and clams, scallops are free-swimming. What most people recognize as a "scallop" is the creature's adductor muscle, which it uses to clap its shells quickly, forcing a jet of water past the shell hinge, propelling the scallop forward. They're surprisingly speedy.

Atlantic sea scallops can have very large shells, up to 9 inches in length. Bay scallops are smaller, growing to about 4 inches. The gender of Atlantic sea scallops can be distinguished. The females' reproductive organs are red while the males' are white.

Scallops are widely considered one of the healthiest seafoods. Made up of 80% protein and sporting a low-fat content, they can help you feel fuller longer and are rich in vitamins and minerals. They are also a great source of antioxidants, which can help protect your body against cell damage linked with a range of chronic diseases.

Here are some other amazing scallop facts that you probably didn’t know:

Scallops have anywhere up to 200 eyes that line their mantle. These eyes may be a brilliant blue color, and they allow the scallop to detect light, dark, and motion. They use their retinas to focus light, a job the cornea does in human eyes.

Like a tree, each ring on a scallop’s shell represents a year of growth, although a ring might also record a stressful incident in the scallop’s life.

The scallop is the only bivalve mollusk that can “jump” and “swim”.

There are more than 400 species of scallops found around the world.

Scallops are one of the cleanest shellfish available. The abductor muscle is not used to filter water, so scallops are not susceptible to toxins or contaminants the way that clams and mussels are.

The lifespans of some scallops have been known to extend over 20 years.

Like all bivalves, scallops lack actual brains. Instead, they have a well-developed nervous system.

Be sure to check out your farmers’ market fish vendor this weekend for a variety of fresh and locally caught fish.

0 notes

Text

Random Assortment of Marine Biology for the Writer - Shark Edition

this past year i took aquatic science, which basically combined oceanography with marine biology while also throwing in a healthy dose of chemistry and physics- 10/10 would take again.

anyway i easily learned more from this class than any other in the past, and i’ve been steadily drawing from this information in my writing, so why not make a list? because there’s like, no way in hell i could fit everything i learned into one post, i’m gonna break it down a bit, beginning with:

SHARKS

- phylum chordata

- sub-phylum - craniata

skulls and spines mean central nervous system (CNS) and a brain

- class chrondrichthyes

cartilaginous fish, i.e. skeleton made of cartilage, also including skates and rays

cartilage - flexible connective tissue made of cells/protein

- characteristics

placoid scales/dermal denticles (literally meaning skin teeth), embedded in the skin, smooth one way and sandpaper-like the other, it’s possible to nick your hand on these

5-7 visible gill slits

spiracles behind each eye, passes water over gills

wing-like pectoral fins, grant lift when gliding through the water

source

- structure/behavior, or in other words, epic adaptations we don’t have

lateral line, nerve line going down the side of the body, many nerve endings, detect vibrations in the water

epic sense of smell, can detect blood a half-mile away

ampullae of lorenzini - pores on their noses, look like black heads, are not black heads, instead detect electrical fields made by the movement of other sea life, i.e. shark food

replaceable teeth, but we all knew that, but also their teeth/jaws are the only pieces we actually find fossilized, because the cartilage is eaten/broken down

continuous swimming, NOT BECAUSE THEY NEED TO SWIM TO BREATH but to stay floating and not sink- more on that later

eye-nictitating membrane - covers eye to protect it while feeding, because sharks are messy eaters

source

source

- reproduction

internal fertilization, meaning they actually do the sex, or as it was explained to me, “they evolved the ability to actually do it”, which is kinda significant in the fish world

males have claspers, tiny fins behind pelvic fins which transfer sperm

there are actually three ways sharks can make babies, it’s wild

oviparity - (ovi=egg), actually lay eggs - horn shark, cat shark, Port Jackson shark etc.

viviparity - (vivi=living), live birth, placental link to young, like mammals - hammerheads shark, basking shark, dogfish shark

ovoviviparity - (egg, living), probably one of the most metal birth processes, the eggs stay inside the female, they hatch, they feed off the remaining yolk/fluids, but in some species the first to hatch eat the remaining eggs/embryos, then they’re born - it’s a fight to the death to even live, all inside the mother

- fun facts bro

dogfish have the longest gestation period of any shark - 18-24 months, meaning the females can be preggers for up to two years

not all sharks have all the fins, a complete list of fins: pectoral, 1st dorsal, 2nd dorsal, pelvic, anal, and caudal

generally the only sharks that will attack people are tiger sharks and bull sharks because they’re just mean as hell, or in other words they have a lot of testosterone, or in other other words they’re the football team at a frat party

sharks don’t like the taste of people, they bite and let go when they realize their mistakes

except for bulls and tigers, as aforementioned

really, they probably won’t kill you, just bite you a little and let go, you’ll be fine

sharks have huge livers which can make up like 40% of their body weight, they don’t have swim bladders, so all the liver oil is what makes them buoyant, but oil is heavier than water, so if they don’t swim they sink - THEY DO NOT NEED TO SWIM TO BREATHE, the spiracles pump water over the gills when they’re still

now if you’ve made it this far you get a cool bit of info about an extinct shark with a weird looking jaw that we’ve found this fossil of:

source

weird right? so we’ve got two guesses of what this could’ve looked like:

source

source

now this thing is being referred to as the helicoprion shark, and it went extinct forever ago so you have nothing to fear - and any images you see of this guy are fake or scientific renderings

next awesome fact, off the coast of Africa great whites actually leap out of the water, and you’ve probably already seen pictures so i won’t bother inserting any

that’s the end of the sharks, probably, i hope i learned you a thing or two, tune in next time when i talk about mollusks, and maybe the source of my favorite conversation starter, barnacles

#sharks#marine#biology#marine bio#marine biology#sea life#ocean#writer#writing#writing struggles#writing support#writing tips#the more you know#great white shark#dogfish#helicoprion#in case you needed something to write about#or if you already wrote it and need to check yourself#in case you were wondering#in case anyone cares#writing help#writeblr#write#marine biology for the writer#or for anyone

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Lou Carcolh, or also known as Snail Dragons, are another prime example of how "dragons" are not an actual official family of creatures. As I have stated in previous entries, the term "dragon" is used for labeling or describing large, intimidating creatures that terrify locals and cause issues. The species that are indeed giant, reptilian monsters are referred to as "true dragons," as the regular dragons can refer to a conglomerate of species that vary wildly in anatomy, class and many other things. Grinning Dragons, Bone Dragons, Arctic Dragons and Snail Dragons all carry the label "dragon," but are so incredibly different from one another that even trying to link them together is silly. I mean, just in those four is a mollusk, a reptile, an insect and a mammal. Quite different indeed! Anyways, I bring this up because this entry is about the Lou Carcolh, which many like to call Snail Dragons.

The Lou Carcolh live in temperate climates, setting up their homes in caves, tunnels, crevasses and other rocky structures. They are solitary creatures, only coming together during mating season. A Lou Carcolh prefers rocky terrain and a place that is either damp or receives a decent amount of rain. As a species, the Lou Carcolh do not need much to get by. They do not require a complex nest, nor a massive territory for hunting. Instead, they like to find a nice, rocky place to hide and then wait there for prey to come by.

These large mollusks are ambush predators, catching prey that walk by their dens. When they wish to hunt, a Lou Carcolh will slowly crawl its way to a hidden spot. Some hide in the darkness in caves, some cling to sides of cliffs and crevasses, while some may even bury themselves in vegetation to hide their mass. Once properly hidden, they will snake their extremely long tendrils out into the open, hiding them in the foliage or blending them in with the rock around them. They will set their trap on trails and other places that show sign of activity and passage. There, their tangled net will lay, waiting for some poor sap to come trundling by. When prey steps amongst their tendrils, they will rise up and snare the creature in their sticky embrace. The tentacles of a Lou Carcolh have a natural adhesive and stiff hairs that allow them to trap smaller prey or properly hold larger, thrashing animals. When a victim is tangled in their grip, the Lou Carcolh will reel them back into their hiding place. The tendrils will bring them to their mouth, where they will inject them with paralyzing venom from their fangs. When prey is immobilized, the Lou Carcolh will seize them in their mouths and begin the slow process of feeding. Lacking powerful jaws for cutting and chewing, the Snail Dragons instead use a saw-toothed radula that takes up their entire lower jaw to slowly rasp away flesh. The backwards facing teeth help keep the victim in place and tear away at them as the Lou Carcolh works its jaw back and forth. Needless to say, being eaten by a Lou Carcolh is a long and painful process, as the victim is usually still alive. The venom only paralyzes your muscles, so it does not kill you instantly. Death will only come through asphyxiation or blood loss, and neither are all that great. The Lou Carcolh will continue to rasp away at its prey until it has broken down enough of them to swallow whole. After prey is consumed, they shall rest and digest for some time, before setting out their trap again. The trapping tendrils of a Lou Carcolh also aid in getting water, as there are small vessels that run throughout the tentacle. When thirsty, they will send their tendrils out to find puddles and pools. The appendages will submerge themselves and siphon water to the main body far away. That way Snail Dragons don't need to go out in the open to get a drink!

Due to their large size and slow lifestyle, the Lou Carcolh can live for quite a long time. Some stories have claimed that certain specimens have been centuries old, growing to a size and strength that is impossible to slay. I have heard some tales that there are a few mountains out there that are notorious for causing travelers and climbers to vanish. They believe that a massive Lou Carcolh lives within the rock, sending out mile long tendrils to catch any who are foolish enough to climb its peak. Some even say that the mountain itself is there shell!

When it comes to reproduction, Snail Dragons are a bit different compared to other "dragons." The Lou Carcolh are hermaphroditic, possessing reproductive organs of each gender. This works to their advantage, as these creatures are quite slow when it comes to travel. When mating season occurs, the Lou Carcolh travel to find pheromone trails left by others in hopes of finding a mate. Since they are slow, this searching can take weeks until they find another of their kind. With that, you don't want the issue where you put all this time and effort only to find that you have tracked down an incompatible mate. Being hermaphrodites, any individual they find can do the job! So when two Snail Dragons come together, they do their courtship and then one (or both) of them fires a "love dart" into the other. These hardened, sharp "darts" are filled with sperm, and are how one Lou Carcolh fertilizes the other. They are located in the same region where the fangs are, developing prior to the mating season. When the time comes, the two shall do their dance and try to strike the other with this "dart." Whoever winds up getting embedded with this structure will be fertilized, allowing them to bear and lay eggs. In some cases, both wind up getting darted, so they both play the egg-laying role. Once the ritual is over, they part ways and head back to their hunting ground. The eggs will be laid beneath the soil and abandoned. The young that hatch will have to fend for themselves.

Due to their large size and odd appearance, the Lou Carcolh are quite famous creatures to the locals. Certain rocky formations are named after them, especially if they look like a snail shell. There is a local vine that is called "carcolh tongue" due to its hairy, wandering tendrils that lay upon the ground. They are usually one of the first suspected when someone goes out to rocky areas and vanish, and many warn one another that "the carcolh will catch you!" The origins of the Lou Carcolh is also a popular tale in the region. The story goes that there was a time, long ago, when the dragons ruled the skies. The massive beasts were so plentiful, that they would blot out the sun for days on end. After years of darkness and destruction, one man decided to finally bring the monsters down. He donned his armor and crafted a great, mighty bow. With arrows the size of lances, he shot the dragons from the sky, causing them to plummet from the sky and splatter amongst the rocks. The dragons tried to slay him, but his abilities with his bow could not be beaten. Others took up weapons like his and they worked to clear the skies of these large creatures. During this massacre, there was a group of dragons who brought themselves to the ground, terrified of the lethal arrows. Seeking to avoid their own demise, they tore the wings from their backs and bound themselves forever to the earth. In time, they slowly became the Lou Carcolh, hiding in caves in fear of this mythical warrior. It is a fun story, but one that carries the same cliche every human tale has. For some reason, humans really like to act like they are the creators or cause of every living thing in this world. Every origin story centers around their actions. It's kind of weird. It's like how there are a large chunk of people out there that think that all of dryad kind was created by a lonely Mycomancer! It's ridiculous! (And it's also a tale I would not read to your saplings, because YIKES!)

Another thing that makes the Lou Carcolh infamous to the region is their "love darts." The large stinger-like reproductive organs are things people have a hard time understanding, and they also create some bizarre scenarios. There was a time, a while back, when people thought that the Lou Carcolh abducted virgins and used their "love darts" to impregnate them with their larvae (That is also another thing that shows up in a lot of human tales: monsters doing naughty things to others. Makes you wonder who comes up with this stuff.). It was also seen as the ultimate sign of humiliation for those who hunted the Carcolh. Since the "love dart" is situated in the mouth, those who get near its fangs or struggle in its grip may accidentally set it off. It has been said that those warriors who have accidentally been shot with this dart during battles usually wander off into the woods, never to be seen again. They apparently were too ashamed to show their faces ever again. The other thing their "love darts" are famous for is outsiders not realizing what they are. Days after the mating process, the "love darts" are pushed out of the body and discarded on the ground. Travelers have stumbled across these strange things and see them as potential weapons. They are barbed, dagger-sized and lightweight, so a little modification would turn them into a decent knife. These travelers would then show up in town and show off their new blade, which would cause every citizen to nearly die of laughter. The terms and names they call these people who wield them are not appropriate, and I cannot write them in here but trust me when I say they are quite colorful and descriptive. It has become a gag for certain locals to craft weapons out of "love darts" and sell them to ignorant travelers, so that they can chuckle behind their backs. They just love the idea of oblivious people walking around with these, thinking they are legitimate weapons and unaware of their origin. Funny enough, I actually do own one of these dart-knives, but I was aware of it when I bought it. I have always thought they were quite interesting and I always wanted to own one. In order to avoid the embarrassment, I told the man who was selling them that I knew what they were but wanted to buy one regardless. I told him that I had "always wanted one" in which he replied to me with a "oh yeah I bet you do," which resulted in a broken nose and a free knife. Despite the comments during the purchasing process, I quite like the blade and it is quite nifty. Though I must warn those who ever think of owning one, make sure you pay attention to which knife you are using for any task you do. When I was staying with some colleagues one time and it was my turn to serve dinner. When it came to cutting up the roasted chicken, I used the knife I had on hand to carve. It took me a second to realize why they were looking at me with such disgusted, horrified looks. Needless to say, no one ate the chicken that night.

Chlora Myron

Dryad Natural Historian

------------------------------------------------------------

A mythical creature that is a fusion of a snail and a snake?! Where has that been all my life?!

And yowzas that last paragraph was not intended when I first started writing this, but it was way too funny for me to pass up. Sorry there, folks.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Walrus Whale

(Above: Male Odobenocetops skull exhibiting sexually dimorphic canine)

With the KT extinction event, and the linked decline in numerous reptile families, multiple environmental niches were opened to other chordate families. Of these the marine environment was perhaps the most opened for expansion. Today the only true marine reptiles are the salt water crocodile, Crocodylus porosus, the Squamata subfamily Hydrophiinae (sea snakes), the Testudines superfamily Chelonioidea (sea turtles), and the marine iguana, Amblyrhnchus cristatus. In their stead, mammals have risen to prominence by adapting to multiple climates and environments. By far the most impressive of these mammalian adaptors have been the cetaceans. While some evolved into the modern Mysticetes, and the rest into the Odontocetes, one group diverged from the dolphin superfamily to create one of the most specialized cetaceans known to science. The nicknamed walrus whale, Odobenocetops leptodon, the only known cetacean exclusively adapted for bottom feeding.

The name Odobenocetops is a mixture of Latin and Greek nomenclature. It breaks down into the Greek words odon, “tooth”, baino, “walk”, and the Latin words cetus, “whale”, and ops, “like”. Loosely translated it means, “whale that seems to walk on its teeth.” The species was extant during the middle Pliocene (5.3-3.6 m.y ago) along the coast of what is now modern day Peru and Chile. It was first described by Christian de Muizon in 1993, with the excavated skulls and assorted bones suggesting that the mammal grew to around 2.1 meters in length, and weighed in at around 150 to 650 kg. Muizon found the species remarkable as “O. leptodon defied the evolutionary Odontocete pattern, by having a rostrum (snout) that is sharply angled downwards and a nasal opening that is drifting back towards the tip of the snout.” [Muizon, C. (2002)].” In addition, the extinct chordate exhibited two rear facing tusks, with the one on the right growing to three times the size as the one on the left in male specimens, giving it its nickname as the “walrus whale.”

Despite a remarkable resemblance to the walrus, detailed analysis of the fossils reveal that the mammal was definitively a Cetacean. It possessed an immobile elbow joint, as revealed by a recovered fossil forelimb. Its skull lacked a true cribriform plate, which separates the nares in other mammal skulls, and instead had a group of foramina that allowed the passage of olfactory nerves to the olfactory lobe. The frontal bone of the skull possessed a large supraorbital process that overhung the eye. It possessed large air sinuses in the auditory region of its skull, connecting to enlarged pterygoid sinuses in the palate. And the narial fossae (breathing passages) were located dorsally, though not as far back as in modern cetaceans.

(Above: Artistic reconstruction of the extinct cetacean)

Although there is a significant anatomical and evolutionary distance from the modern walrus, Odobenus rosmarus, the similarly tusked Pinneped is perhaps one of the best analogs to the theoretical behavior of the extinct cetacean. Walruses have three uses for their elongated canines. Firstly, during winter they aid in opening and maintaining holes in the ice, an unlikely usage for Odobenocetops tusks due to their warmer, eastern pacific range. Secondly, they help to stabilize the walrus as they flush benthic mollusks out of marine sediment. A behavior that is defined in the Odobenocetops nomenclature, and suggested by similarities between the feeding structures of both walrus and Odobenocetops skulls, both having curved gripping mandibles and oversized buccal cavities capable of sucking soft bodied mollusks from their shells. Lastly, in social groups, males utilize them for dominance displays, with the males possessing the largest and strongest tusks typically dominating the herd.

(Above: Walrus flushing marine sediment to locate mollusks)

Dominance displays involving exaggerated canines are readily observed in the modern Ondontocetes that possess them. Beaked whales, such as Blainsville’s beaked whale and Cuvier’s beaked whale, are covered in long thin scars from male dominance displays involving their protruding canines. Bull narwhals rub tusks in a behavior known as tusking, where they establish hierarchy in social groups.

Bottom feeding is similarly not limited to Pinnipeds. The gray whale, Eschrichtius robustus, has been commonly observed forcing its jaw through sea floor sediment and straining the mud through its baleen to capture invertebrates. The Humpback Whale, Megaptera novaeangliae, scrapes its jaw along the seafloor to scatter sand lances out of the sediment and towards the surface, where the rorqual can ensnare shoals in a bubble net and consume literal tons in a single lunge feed. And the narwhal, the closest cetacean physiologically to the Odobenocetops, feeds on bottom dwelling halibut and other flat fish during the Arctic winter.

(Above: Bottom feeding grey whale)

The narwhal, Monodon monoceros, and the closely related beluga, Delphinapterus leucas, are considered to be the closest living relatives of Odobenocetops. Like the Odobenocetops they have flexible necks. In fact, they possess the only examples of flexible necks in living cetaceans. This is due to jointed (as opposed to fused) cervical vertebrae. The Odobenocetops had similar unfused cervical vertebrae, creating a 90 degree range of motion for its head and allowing it to maneuver its tusks. A similar behavior is observable in modern narwhals, which use their flexible necks in conjunction with their elongated canines to stun Arctic cod in flicking motions. The rostrums of the beluga and narwhal are reduced, although their skulls are designed to support melons which enable echolocation, which the extinct cetacean lacked. Also similar to Odobenocetops, the narwhal has evolved so that it possesses a pair of asymmetrical exaggerated canines, though they are not sexually dimorphic like Odobenocetops. In most narwhals, the left canine curls into a tusk that extends through the upper lip up to a length of eight feet, while the other adapted canine rarely protrudes past the skull. There have been occasions where both tusks have developed fully, with a higher percentage of these instances occurring in females.

(Above: Unfused beluga cervical vertebrae)

What we observe in the Odobenocetops is the product of a fascinating evolutionary path that led to a bottom feeding cetacean, and left behind two of the most unique of the modern toothed whales. While transitionary fossils between this unconventional animal and other toothed whales have yet to be found, its importance as a part of the evolutionary history of marine mammals cannot be understated. It raises fascinating questions regarding what evolutionary pressures would push the cetacean body plan to exploit the ocean floor, and what kind of environmental and biological factors made this the best evolutionary route for toothed whales off of the Pacific coast of South America.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Episode 6: The Age of Mammals

The following is the transcript for the sixth episode of On the River of History.

For the link to the actual podcast, go here. (Beginning with Part 1)

Part 1

Greetings everyone and welcome to episode 6 of On the River of History. I’m your host, Joan Turmelle, historian in residence.

Welcome to the Cenozoic Era! This is our geologic era, the one to which we’re currently still apart of. The last 66 million years of the Earth’s history, from the great extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous Period, encompasses the development of the modern world – Cenozoic, translated, means “recent life”. In essence, we’ll be staying in the Cenozoic for the remainder of this podcast. Like the Mesozoic, the Cenozoic encompasses three periods, but because of the sheer number of important events that unfolded within this time, it is perhaps more feasible to progress through this time by epochs, those categories of time that make up periods.