Photo

“The World of Lore: Wicked Mortals” by Aaron Mahnke

Things that go bump in the night are scary. A sound that comes from seemingly nowhere. A creature which seems totally alien to anything you’ve seen. The mystery of an object that was in one spot and then another without anyone touching it. These common tropes in horror still in use today.

Sure, these things are scary, but the people we live amongst have a capacity for violence, physical and psychological, which we usually learn of after the fact. And this mystery, of what lurks within each of us, makes humans not just scary but terrifying.

The exploration of some of the more infamous historical instances of people’s capacity for violence against their fellow man is what drives the second installation in Aaron Mahnke’s “The World of Lore” series, subtitled “Wicked Mortals.”

Tales of serial killers, murderers, and other scoundrels abound within the pages, including H. H. Holmes and his famous murder castle, a woman who worked as a nurse but was really killing her patients, and a few men who saw the profit in death and were looking to make a quick buck.

In a deeply sadistic and dark way, the book is fun and hard to put down. Each category is broken down into smaller sections, each telling a separate tale, and the small sections make this, sadly, a quick read.

If you are new to the world of Lore, you will be hard pressed to put this down without finishing it quickly. You will be disgusted, but intrigued, and you will want to read more.

However, if you are not new to Lore and have listened to the podcast for a while, many of the sections will seem familiar. Much like the first book in the series, “Monstrous Creatures,” each section is like reading a transcript of its corresponding episode.

This isn’t bad though. Even if you have listened since episode one, the book is still enjoyable, and you will more than likely come across things you probably forgot about.

So if you are into the dark and macabre side of human nature, pick this book up, and explore the grisly nature of people.

4/5 cups of coffee

#lore#world of lore#wicked mortals#monstrous creatures#aaron mahnke#literature#review#podcast#h.h. holmes#serial#serial killer#murder#murders#death#grisly#the-bookist#the bookist#book#books#bookworm#bookworld#bookreader#book review#bookthings#booky#bookish#bookinstagram#bookoholic#bookpost#bookaholic

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Not That Bad edited by Roxane Gay

Over a dozen times in the past few years, news articles and reports have focused on a celebrity who has been accused of sexual assault or sexual misconduct.

The phenomenon has become so prevalent it has spawned the Me Too movement. Me Too has also become a verb i.e. to be MeToo’ed. See the Kanye West song Yikes for an example of Me Too being used in such a way.

But these accusations are always met with questions. Not questions for the accused but for the victim.

Why didn’t you come forward when it happened? Why did you let it happen not once but twice? Did you do something to lead this person on? Were you drunk? What were you wearing? Was this all just a misunderstanding?

It’s like asking someone who was abducted: Why didn’t you try to stop this? Did you do something that made this person want to abduct you? Maybe your abduction was all just a misunderstanding?

The treatment of sexual assault victims is horrendous, and for anyone who says, “Well, they just want to get money,” an estimated 2-8 percent of sexual assault cases are based on false accusations.

To put that in perspective, you have a greater chance of dying while base-jumping. Yes, it happens, but not at the rate people would want you to believe.

What is lost in all this is how the sexual assault can affect a person for days, months, and years after it occurred.

That is what Not That Bad, an anthology edited by Roxane Gay, hopes to bring attention to.

The book collects essays and writing pieces of men and women who have either been sexually abused or assaulted or who have been affected by rape culture.

The resulting works are nauseating and difficult to read, but that makes them all the more important.

Many of the essays focus on the after effects of the misconduct.

How one woman has to endure perverted catcalls while out with her young child. How one man fights the trauma of his abuse into his adult life. How another woman tries to explain how rape culture places all the blame on the victim of abuse and not the accused within the court of law.

And more importantly, we see the psychology of an assault victim and what runs through their minds.

Why didn’t you say something before? Maybe the person was scared because the assault happened when they were 12 and it was an adult authority figure who abused them and they felt powerless?

Why did you let it happen again? What if the person abusing the victim was their father and they had spoken out in the past, were promised it wouldn’t happen again, and yet it did?

What about your clothes? Shut the fuck up.

The book is unlike anything you will see from any of the reports online and on television, and it is not easy to read either. But it is a good place to start to try and understand how victim-blaming and rape culture as a whole can be hurtful to victims, their families, and society.

4.5/5 cups of coffee

#not that bad#roxane gay#review#literature#dispatches#essays#rape culture#sexual assault#sexual misconduct#book#books#edited#anthology#collection#the-bookist#the bookist#bookworm#bookworld#bookreader#book review#bookthings#bookish#bookoholic#bookpost#bookaholic#bookaddict#bookgeek#bookgram#bookguy#bookhoarder

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Borne by Jeff VanderMeer

Have you ever raised a child? You watched them as they grew from a small bean to a sentient creature within the world? You saw them learn, you saw them get hurt, and you watched them make their own decisions. And finally, you watched as they went off and fulfilled their own purpose?

This is the model of the critically praised, and highly lauded novel Borne by Jeff VanderMeer.

The eco-author, known for his Southern Reach Trilogy, tries his hand at the dystopian-future genre in his latest book.

But unlike the stereotypical dystopian-future novel, where the characters are simply trying to survive or figure out a way to reverse their dystopian environment, Borne focuses on the familial dynamic within this environment and what it means to be a parent.

The narrator is named Rachel, and she and her male-counterpart, named Wick, live in a bombed-out apartment complex where they have figured out how to survive in an environment filled with radioactive streams and animals that might be people that might be animals.

Within the first few pages, Rachel finds a small creature, amorphous blob is more accurate really, which she names Borne. She brings the creature back to her home and begins to raise it as a child, even though, you know, it’s a blob.

What ensues is more parent, self-help book rather than a science-fiction novel.

We watch as Borne begins to move around, ask pesky questions like “What does that word mean?”, and learn to morph into larger and larger sentient and non-sentient objects alike. You know, normal kid stuff.

And though Rachel does a good job with pretty basic parenting, Borne’s rearing begins to take a weird turn as we learn that it learns best when it eats things.

And by eat things, I mean totally consume them in what I can only imagine is similar to an amoeba eating something. Borne collects whatever he has eaten’s knowledge and says the things that have been consumed are not ‘dead’ despite all the evidence to the contrary.

The book is weird, but what do you expect from an author considered part of the New Weird authors? But for all its strangeness and oddity, it is a fun read which will make you think about life, parenting, and the intersection of technology with the natural world.

Oh, and did I mention there is a giant flying bear? Yeah, there’s that too.

4/5 cups of coffee

#borne#Jeff Vandermeer#author#book#review#eco-author#southern reach#trilogy#parenting#self-help#literature#science fiction#science-fiction#science#sci-fi#scifi#bookworm#bookworld#bookreader#book review#bookthings#booktag#bookish#the bookist#the-bookist#bookoholic#bookpost#bookaholic#bookaddict#books

120 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen

As Americans, we all know about the Vietnam War. We may not want to admit we know about it, or that we took part in it for that matter, but history has already been written. We can’t deny it any more than we can deny the sun.

And as much as we may know about the war, we only really know about our side — the American side. And by that, I mean the American soldiers that went to Vietnam: the soldiers who made it back alive, or the ones sent back who had died.

However, we don’t know much about the people of North or South Vietnam. They are like set pieces in our collective imagination.

Enter the Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning novel follows a north-Vietnamese spy working in the south, and eventually in the US, in the wake of the Vietnam War.

The dualism of the main character is a point continuously brought up throughout the narrative. His lineage as half-Vietnamese and half-French makes him untrustworthy in the eyes of his fellow Vietnamese, and the education he received in America makes him a threat to some of his comrades.

Other dichotomies present themselves throughout the book, and the point is to show they aren’t so different from each other. They are different sides of the same coin or mirror images of themselves.

We also see how difficult it is for refugees to make their way in America after leaving their country. An established Vietnamese soldier has to work a third shift clerk job to make ends meet and our narrator takes up odd jobs here and there to support himself because he can’t find steady work.

It’s not for lack of trying he can’t find a job. No place will hire him.

For all it’s seriousness, the work is also funny. Mostly through clueless characters.

One character, who is a professor, takes it upon himself to tell our narrator about Vietnam, even though the narrator grew-up there, and our narrator grins and bears his teeth through the whole experience.

Another character, a film director, asks for the narrator’s help in getting his movie about the Vietnam War correct, but whenever our narrator tries to make a correction, “the auteur” as he is called, grows more disdainful and eventually tries to kill our narrator.

Both of these characters feel like caricatures of ugly Americans, i.e. Americans who put themselves first in all manner of things.

We see the resentment this can cause in our narrator as he becomes more and more disillusioned with American culture and the sense of entitlement it breeds. At one point, our narrator says he doesn’t understand why some people want to come to America so bad because of this entitlement.

Some might say this way of thinking is a bit problematic, given how many people flee their countries to escape violence and to save their and their family’s lives.

The people who say this would be right, but the novel does not ignore this issue.

Rather it shows how things are less than ideal when you are forced to relocate to another country for fear of death. Even though you might be safer, the culture is not the same, the people don’t understand you, and the government treats you like a second-class citizen.

With all these things taken into account, it is easy to see why refugees would still want to go back home.

Ultimately, the book is funny, it’s smart, and it makes you think outside of yourself. And don’t just take my word for it. The book didn’t win the Pulitzer for nothing.

4/5 cups of coffee

#the sympathizer#Viet Thanh Nguyen#review#book review#the bookist#the-bookist#literature#vietnam#vietnam war#vietnamese#war#culture#movie#book#books#bookworm#bookworld#bookreader#book recommendations#bookthings#bookish#bookinstagram#bookoholic#bookpost#bookaholic#bookaddict#bookgram#bookgeek#bookguy#bookhoarder

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

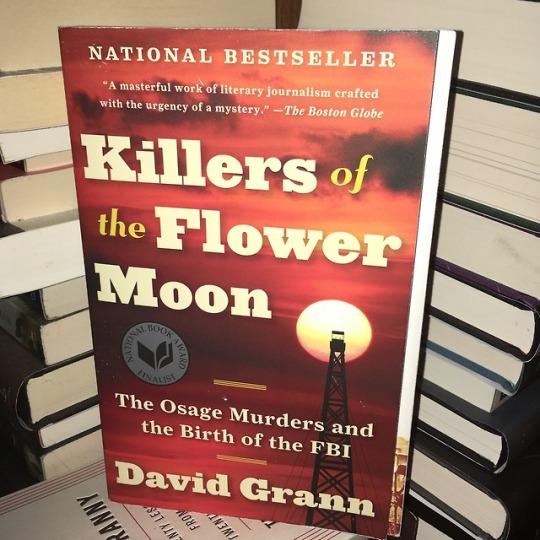

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann

The true crime genre has been a part of our culture for a long time and has seen a major increase in material recently.

Spurred on by the popular literary work In Cold Blood, then with a cultural fascination with the O.J. Simpson trial, and recently with wildly successful Podcasts such as Serial, the genre has exploded on the market and more and more crime stories are making their way to our collective subconscious.

Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann is a recent entry in the true crime canon, and the book is a worthwhile addition.

The story focuses on the Osage Reign of Terror, a period in the 1920s where members of the recently made rich Osage tribe were dying at a rate astronomically higher than other US citizens of the time per their population size.

A young J. Edgar Hoover sees this case as a way to prove himself and his own investigative techniques as the way of the future in policing and bets it all on solving the case.

What unravels across the pages is a story rivaled by spaghetti-westerns and noir films. Cowboys, desperados, bank robbers, corrupt cops and politicians, and cattle farmers collide as we are led through the history of the murders of the Osage and the conspiracy behind it all.

The investigation into the murders and the connecting of all the points is interesting, but what is really striking about the story is the treatment of the Osage by other Americans.

As mentioned above, the Osage had recently come into money as their reservation was on top of an oil well. They rented their land off and collected money from the people who came in and mined the oil, putting thousands of dollars in their pockets. This made the tribe one of the richest groups of people in the world at the time.

However, the Osage weren’t allowed direct access to their own money and had to have a guardian sign-off on their purchases because the US government didn’t think the Osage could be trusted with their own cash. Because they were Native and therefore couldn’t handle their funds i.e. because racism.

This leads to a convoluted legal and economic system where the guardians owned or knew people who owned businesses in the area where they inflated the prices of menial things in order to rip the Osage off and make huge profits.

Ultimately, this greed is proven to be the driving force behind the murders of the Osage as each murder transfers the land rights of the murdered Osage to either their greedy guardians or a family member who is married to a guardian.

The injustice and the treatment of the Osage is ludicrous, and it is something that feels culturally lost. We know about the injustices against Native tribes from hundreds of years ago, but any recent injustice is either forgotten or not widely recognized.

While this is a true crime story, it doesn’t feel like a classic crime story with a single person to blame or a small gang of people at fault. No, the people at fault were those responsible for the system of racism which didn’t trust the Natives and subsequently treated them as children, leading to their widespread murder.

Overall it’s fun, it’s interesting, and it’s worth a read.

3.5/5 cups of coffee

#killers of the flower moon#david grann#true crime#genre#history#nonfiction#literature#review#book#osage#tribe#oil#reign of terror#murders#death#conspiracy#fbi#j edgar hoover#greed#racism#native#american#wealth#book review#books#bookworm#booklover#bookworld#bookreader#book recommendations

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

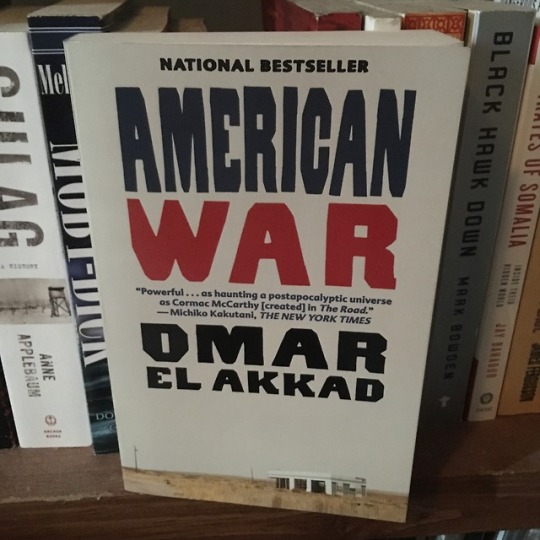

American War by Omar El Akkad

I’ve heard time and time again that we, the American public, are heading towards another war with ourselves. I would say another “civil war” but there’s nothing civil about killing another person or people in the name of… whatever.

But you’ve heard the reasons why on the news, but the news hasn’t taken it far enough to suggest it may lead to another war.

“We are divided politically, culturally, religiously, and there’s no room for debate any longer,” they say. We are also seeing a rise of anti-intellectualism which has scared people from trying to understand the world around them and regard people who know more than them as “disconnected” or simply assholes. And the divides around people are growing more and more every day.

The debut novel from journalist Omar El Akkad, simply titled American War, takes these divides to their bitter end.

Set about 75 years in the future, America has lost its east coast, Florida is submerged except for a few islands, much of the southwest is under the protection of Mexico, and the former states of Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia have seceded and become what is called the MAG. A map towards the front of the book gives a good idea of what the country physically looks like.

But the main story follows a young girl, named Sarat, who was born in lands surrounding the MAG, known as ‘purple country,’ and see her grow into a mythic figure in the MAG’s fight for independence.

The explanation of how an extremist can be born and how they operate in the world is the main draw of the book, and it is pulled off fairly well. Unfortunately, other parts of the novel raise more questions than answers.

Off the top of my head, there are three main issues.

The first has to do with the reason behind the war.

In this future, the rising sea levels from global warming are the reason the east coast and Florida are gone, not to mention rivers and other bodies of water have caused the interior of the land to change as well.

With that being said, I can’t help but think the people who live in the MAG, who are close to the rising seas, would understand the reason the land is underwater is global warming brought on by a dependency on fossil fuels, yet the MAG cling to fossil fuels with all their might and refuse to give up gasoline-powered machines. This is also the main reason for their secession.

I would think the people who live in these regions, the people who have witnessed firsthand the destruction brought on by the sea, would be like, “You know what, maybe we don’t need gasoline so much. Life is better.” But apparently people’s observational skills are greatly reduced in the future, or the people are willfully ignorant (anti-intellectualism and all), or both. Why not both? So that’s issue one.

Numbers two and three are one in the same but with different characters.

Sarat’s mentor into extremism never gives a good reason for his support of the people fighting for the MAG. Is it money? Is it power? Does he believe in the MAG’s cause? He himself is from the north so it can’t be some sense of pride in his home, it wouldn’t make sense.

His only explanation is that when a southerner says they will do something, they do it, implying northerners aren’t honest or don’t stick to their word. But this is out of line with his character since he himself is a grifter and a user of other people. Why does he use them though? We don’t know. He just does, I guess?

And the second character is the mentor’s associate who provides backing for the MAG rebels in the form of military hardware and supplies. But his motivation, or what he gets out of helping the people in the MAG, is never fully explained either.

I can’t believe he is doing this out of the goodness of his heart. And he isn’t even from this part of the world so he has even less of a connection to the war than the mentor.

When asked why he helps by Sarat, he says, “Every war is an American war,” which may be true now in 2018, but the fact that the southwest is a protectorate of Mexico tells me America has lost its standing as a global influencer. Shit has to get pretty bad when people are saying, “Yeah, I want to be protected by the cartels and their people, not you.”

So these two characters’ motivation doesn’t make sense, and it’s not hard to fix these things. Just throw in a few lines of dialogue about how these two people are gunrunners who sell to the highest bidder. Or how they can’t imagine not being a part of a war since they were first soldiers years and years ago. Done. Problem solved. But nope, not even that.

Despite these shortcomings and others, it’s still an interesting read for no other reason than it’s a glimpse into another inner-American war and the birth of a type of extremism.

It’s interesting and fun and you might gain an understanding of why someone might fight for something along the way.

3/5 cups of coffee

#American War#omar el akkad#review#book review#book#books#literature#future#America#war#gasoline#extremism#South#North#Mississippi#Alabama#Georgia#Mexico#lit#little brown#book questions#bookworm#bookreader#bookr#Book Recommendations#bookthings#booky#bookish#the bookist#the-bookist

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

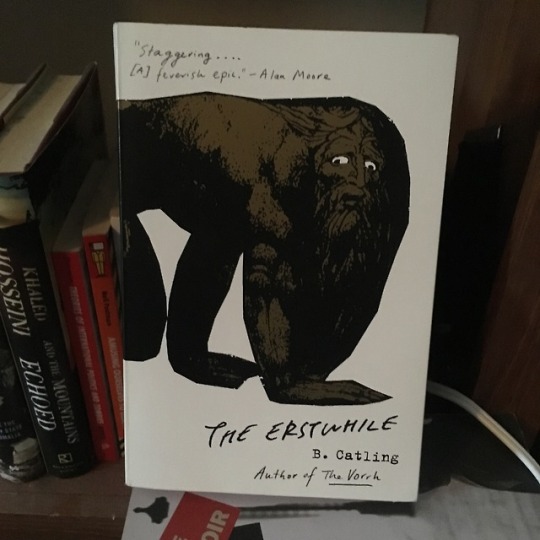

The Erstwhile by Brian Catling

The Vorrh, the first fantasy book in a trilogy by Brian Catling, is one of my favorite fantasy books of the 21st century. The book was consuming like it’s namesake, and I found myself falling deeper and deeper into the mythology of this historically, geographically, and culturally, alien world.

Set in the 1920’s in a colonized part of Africa on the edge of the legendary forest known as the Vorrh, the book explores what is different about cultures and people, the importance of stories and myths to people, and how all of these things intertwine and are vital to the survival of the others.

It is fantasy with biblical references and a hint of the historical. It made sense and was fun all at the same time, a feat not many books can pull-off, or pull-off well for that matter.

So when I started the Erstwhile, the second book in the trilogy, I was excited. I was looking forward to what would come. Now though, I feel like I was robbed.

The Erstwhile happens about nine months after the events of the Vorrh. We see many of the same characters, the return of a few of those who died in the previous installation, and we meet a few new ones like any good sequel. The style is consistent from the Vorrh to the Erstwhile, and to be honest, that is the best part of the book. The prose.

Everything else about the book is frustrating. It’s like watching Pirates of the Caribbean 2. The first of the series was enjoyable so you are expecting the same from the sequel, but you feel letdown more often than not.

Characters are arguably the most important part of any narrative, and many of the main characters this time around read like assholes. One is a sex-crazed monster, a few abduct a child for some reason, and one is an arrogant fanatic of sorts. The few main characters the reader can really root for include the woman who had her child abducted and a Jewish-German doctor who never sets foot near the Vorrh.

And some of the storylines within the plot feel like they would be much more rewarding if they weren’t cut short. One, in particular, is reminiscent of Prospero and Caliban, and I was genuinely excited to see how this would play out only to have its legs cut out from under as the Prospero in this situation kills the aforementioned Caliban.

In other storylines, I found myself willfully rooting against the main characters and wanted to see them fail. In the plot to locate the Limboia, the brainless slaves used to cut the trees of the Vorrh for production, I wanted the expedition to crumble. Not just because, you know, slavery, but also because the leader of the expedition is a pompous asshat who needs to be cut down. Literally or figuratively. I’m not picky.

The plot of the Jewish-German doctor feels out of place since he never goes to Africa. No, he is hundreds of miles away in Europe. His only connection to the story are his interactions with the Erstwhile, abandoned angels who were supposed to guard the Tree of Knowledge in the Garden of Eden, but they weren’t very good and failed spectacularly. His plot has tension and mystery, and really I would have read the book if it were dedicated to him and his journey. But no. He gets to share the book with all of the ‘meh’ of the book.

What else was disappointing was the lack of the Vorrh. The first book went to great lengths to have this mythic forest not be a set piece but an independent and seemingly sentient character. That feels lost in the sequel as the forest is mentioned mostly in passing. Sure, the expedition for the Limboia takes place in the Vorrh, but the danger of the forest established in the first book isn’t there this time around. At first, it was palpable. There was dread when the forest was mentioned, and the idea of the forest fighting back was all too real. Now the forest is like a grove of Venus flytraps. Unless you are a fly, there is no reason to be afraid.

Beyond that, the book feels incomplete. Where it’s predecessor could stand on its own as a good fantasy book, the Erstwhile is dependent on the first and hopefully the third book of the series. We are left with more questions at the end of the book than at the beginning and close to no resolutions. Almost like this was a marketing ploy to get us to buy the last book in the series so we can have these questions answered.

Will I buy the third book when it comes out? Yeah. And I can only hope it returns to the quality of the Vorrh and not of the Erstwhile.

2.5/5 cups of coffee

#The Erstwhile#Brian Catling#B Catling#review#literature#fantasy#myth#The Vorrh#trilogy#forest#Africa#Garden of Eden#angels#Tree of Knowledge#Prospero#Caliban#shakespearean#book#books#the-bookist#bookworm#bookworld#bookreader#book review#bookthings#bookish#the bookist#bookoholic#bookpeople#bookaddict

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

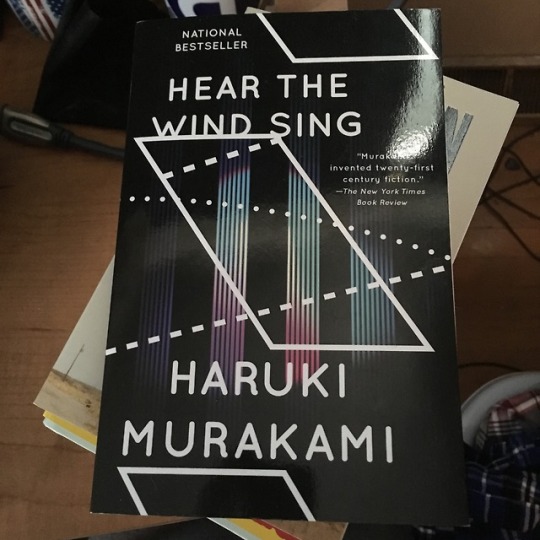

Hear the Wind Sing/Pinball, 1973 by Haruki Murakami

Few authors have had over 30-years of staying power, and even fewer are internationally renown. Yet Haruki Murakami has proven to be a fount of the mythical, mystical, and magical since the beginning of his prolific writing career in the late-70s.

With a writing resume that includes short stories, novels, and plenty of nonfiction, Murakami has established his own distinctive style, as well as his own unique symbolism. In any given work animals are everywhere, especially cats, hidden worlds are just beyond a character’s front door, and people have unique names or unforgettable physical qualities. These make reading the latest Murakami book like going to a concert of your favorite band. The setlist and experience might be different each time, but you still recognize and sing along to each song regardless.

With an author like Murakami then, it is always fun to go back to their early work and see what they tried in their early years and what stuck.

Hear the Wind Sing and Pinball, 1973 are Murakami's first novels and they are two distinct works. They work independently of each other, but technically Pinball is a sequel to Wind. This alone makes them unique in Murikami’s canon as he usually doesn’t write sequels.

For being Murakami's first published novels, there are many tells which give them away as his. They aren’t as mystical as 1Q84 or as magical as The Wind Up Bird Chronicle, but the odd set pieces and seemingly normal reactions to said pieces is all too familiar. Even some of the names, like Rat for instance, scream this is a work of Murakami.

The writing style is also familiar, but not for Murikami. Rather, the short, choppy sections and terse style feel like something written by Bret Easton Ellis sans serial killers or affluent pricks. This style would become prominent in the late-80s, early-90s, but given these works were written in the late-70s, it’s safe to say Murakami was at the forefront of this paradigm shift.

The thing that falls flat about both of these stories are the plots. Both works feel like they are leading somewhere like they have something to say, but they keep holding themselves back, never getting to where they want to go.

Characters are also not as developed as people might be used to in later Murakami works. For Wind, they feel flimsy and their actions don’t feel substantial. In Pinball, one character’s whole plot could be cut and the work would stand, albeit much shorter. And these make both books feel bloated. Not that the extra fat matters much as you can sprint through both books in an afternoon.

Overall, they aren’t bad reads by any means, but they aren’t fantastic. It’s like being a senior in college and looking back on some of the papers you wrote when you were a freshman. You recognize your own writing, but it’s easy to see how much you’ve grown.

2.5/5 cups of coffee

#hear the wind sing#pinball 1973#haruki murakami#novels#literature#1q84#the wind-up bird chronicle#early work#bret easton ellis#writer#book review#review#book#books#bookstagram#bookworm#bookblogger#bookblr#bookreader#bookish#the bookist#the-bookist#bookoholic#bookaholic#bookaddict#bookgeek#bookgram#bookguy#bookhoarder#booklover

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

We Were Eight Years in Power by Ta-Nehisi Coates

It’s the elephant in the room of American politics. The big R word, that some think doesn’t exist and has never existed until President Obama took office in 2008. The word is racism.

Racism isn’t the point of We Were Eight Years in Power, but it certainly is the overarching theme the collection builds towards.

Even the title of the collection hints at this. The title is not only an allusion to the Obama presidency, but it is a quote from Thomas E. Miller, an African-American politician elected to positions in both the Senate and House of Representatives in post-Civil War South Carolina.

As a politician, Miller was said by WEB Du Bois to exemplify “good Negro government.” He fought for the civil rights of other African Americans in the South, helped to establish what would become the historically black college South Carolina State University, and continued to be active in politics after he left office, stressing that racism not only hindered the development of African American communities within South Carolina, but the state as a whole.

Miler played by the rules, but as soon as he left office racist politicians in South Carolina got to work at dismembering the work he had accomplished.

This is the crux of the collection. That President Obama played by the rules to become president and while in and out of office, was crucified at every twist and turn, from big issues such as his use of drones to kill American citizens, to the famous ‘tan-suit’ controversy. While the controversies were magnified, the achievements of the Obama presidency were diminished, and many have been fought and erased after the appointment of President Trump to the office.

The deletion of these achievements is not new as Coates points out. Historically, whenever the African American community does well, racist legislature rears it’s monstrous and deformed head to try and beat it back or destroy the successes.

While Coates presents the struggles for equality in America, he also reflects on his life during the Obama presidency. We see his rise from a blogger who was only read by his father, to a level of fame he struggles with after the publication of Between the World and Me.

These sections of the collection dedicated to showing the person that is Ta-Nehisi Coates offers a kind of parallel to the essays and the point they are trying to make. As Coates rises from a blogger to a writer for the Atlantic and beyond, he tries to show the rise in racist sentiments throughout the country as the Obama presidency comes to an end.

Coates’s essays won’t change anyone’s mind politically, and people who read the collection will have their ideas, good or bad, solidified. They won’t change everyone’s mind, but they will make people willing to have their mind changed think.

3.5/5 cups of coffee

#we were eight years in power#ta nehisi coates#review#Collection#essay#nonfiction#the Atlantic#President Obama#President Trump#racisim#book#reading#books#bookshelf#bookworm#book review#book recommendations#bookreader#bookish#the-bookist#the bookist#bookoholic#bookaholic#bookaddict#bookgeek#bookgram#bookhoarder#book journal#booklover#booklife

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Line Becomes a River by Francisco Cantu

For many Americans, the southern border with Mexico is little more than an alien concept which has polarized friends and family who have never been to the border, seen the landscape which engulfs it, or conversed with anyone who has endured it. We hear about the border via the talking-heads on television, and we learn about the issues surrounding it from our respective sources of news, right, left, or center. The border is our Hadrian’s Wall, mythical and story-riddled, protecting us from crazed barbarians and the cartels they belong to.

But the account Francisco Cantu gives in “The Line Becomes a River” lacks the spin political pundits often place on the border. Instead, Cantu, who worked for the border patrol, gives his own assessment of the region and how it operates.

Cantu sees the border as equal parts war zone and no-man’s land.

War zone in how agents are led to believe that every person coming over from Mexico has some sort of cartel tie. How in their training, they are shown pictures of what the cartel does to people they are at war against, which leads the agents to have a negative and suspicious view of everyone that crosses. They are constantly on guard and never wholly view people crossing the border as people. These images and the feeling of being at war stays with Cantu as we see him become paranoid that cartel members are following him back to his home, and this leads to Cantu realizing he needs to get out of the field.

And he also presents the border as a no-man’s land, especially in the summer months. As people try and cross the desert in the heat and humidity, death is almost certain without proper provisions, and the border patrol is all too aware of this. The see the corpses of people who tried to cross riddled throughout the land. Men, women, and children, all swallowed by the land in their attempts to come to America.

Both of these have a lasting impact on Cantu as a character within his own story, and both bring the realities of the border to ahead. They also influence Cantu later as he attempts to make amends for all the families he feels he ruined by working with the border patrol. Amends which come in the form of trying to keep a family together.

The father of a family he knows attempts to cross the border back to the US, but Cantu tries to help the family as much as he can after the father repeatedly fails. He warns the family not to allow their father to cross in the summer, he calls in favors to other border patrol members, and he uses his inside knowledge of the system to try and help the family.

Whether or not Cantu’s redemption is dramatized or not doesn’t change the rest of the story of the border. These acts of grace don’t change the gaping maw of the desert or the dangers inherent in trying to cross the border. It adds a human element to the story and makes these dangers feel much closer to home and forces the reader to empathize with the people who cross the border for a better life.

3.5/5 cups of coffee

#The Line Becomes a River#francisco cantú#review#book#literature#nonfiction#border#united states#mexico#border patrol#border agent#desert#environment#politics#illegal#lit#bookish#bookblr#books#bookstagram#bookworm#the-bookist#coffee#bookworld#book review#book talk#bookaholic#bookaddict#bookgeek#bookgram

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us by Hanif Abdurraqib

Critics have always been maligned and slandered in a similar way to teachers. A quote describing teachers is, “Those who can, do, and those who can’t, teach,” while a quote about critics is, “A critic is someone who knows the way but can’t drive the car.”

While these quotes may exemplify a distaste for these two professions, if someone were to say either of these, you can guarantee they had not read the book of critical essays They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us by Hanif Abdurraqib which acts as a book of critical essays on music which also tries to teach readers about cultures many of them may not come into contact with.

Take his essay on the anniversary of the Wonder Years’ “Suburbia I’ve Given You All and Now I’m Nothing.” While the album can be lumped in with the other emo/pop-punk albums of the mid and late 2000’s, Abdurraqib argues the album takes an honest look at the sadness and depression everyone feels from time-to-time. How the band says “I’m sad like you are, and I can’t promise to fix this, but we’re going to be here together,” something that no other band in the genre was willing to say in such an honest way at the time.

The essays aren’t only concerning music. Many of them also deal with social justice issues in the US. The essay “It Rained In Ohio On The Night Allen Iverson Hit Michael Jordan With A Crossover” tackles code-switching in the African American community, especially on a professional level.

Abduraqqib likens Jordan to the prim and proper African American man who tones down his blackness for the predominantly white owners of the NBA, while Iverson doesn’t hide who he is from the cameras or the league owners. Jordan is more King while Iverson is more Malcolm.

And this comes to a head with the infamous practice rant. While many remember Iverson taking a defensive stance when asked about why didn’t go to practice, what is forgotten is how Iverson was still coping with the death of one of his best friends. How he was going through a rough time in his life and all anyone wanted to do was rail against him for his behavior on and off the court. He should have been cool and collected people thought. He should have left his emotions out of the game. But Iverson played his game the only way he knew how, with his heart, for better or worse.

After each essay, I felt the need to take a second the just sit with what I had just read. To savor what was written as well as to soak it in. To internalize it, and to learn from it.

5/5 cups of coffee

#the-bookist#they can't kill us until they kill us#hanif abdurraqib#review#literature#lit#essays#music#culture#The Wonder Years#Allen Iverson#Michael Jordan#coffee#bookshelf#book#books#bookworm#bookish#bookblr#bookstack#bookstagram#reading#read#book addict#book review#book reader#bookofthemonth#bookblogger#bookgeek#Ohio

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Feel Free” by Zadie Smith

The current cultural landscape is a wasteland littered with superheroes, fast cars, and enough visceral responses to elicit bar-fight-style brawls out in public.

It is refreshing then to read the essays in “Feel Free” as they feel like a cerebral rollercoaster, full of inverted perceptions on our current state of affairs as well as an in-depth look at things people take for granted.

Take for example her essay on Facebook titled “Generation Why.”

Smith compliments Zuckerberg for the achievement of developing one of the largest online communities, but she also points out some negative sides to Facebook. How some people use the social media platform in a solipsistic manner to confirm their own views of the world.

But the essays are not limited to commentary on our social interactions. One focuses on an interview with Jay-Z, and how Smith compares the rap superstar to “Paradise Lost” author John Milton. How both employ the power of boasting to further their artistic forms to reach the apex of their respective forms.

The one section which I could do without is her most lengthy set of essays in the collection, all under the header the Harper’s Columns. This is not to say these pieces are written poorly by any means. They are stylistically quite good, as is to be expected from Smith. No, they just feel out of place in the larger context of the collection.

While the other essays are concerned with social issues, cultural pieces, and experiences strolling through a garden, this small collection feels like a friend talking to you about a book you haven’t read or significant points in a movie you haven’t seen. There are no spoilers per se, just a bit of confusion if you haven’t read the books she is reviewing.

The essays are thoughtful and fun though. Readers will laugh from time-to-time, and they will also stop to ponder art, politics, and everything in between.

3.5/5 cups of coffee

#the-bookist#Feel Free#Zadie Smith#review#nonfiction#essays#collection#Facebook#Jay-Z#Harper's Column#culture#art#politics#literature#book#books#books and libraries#bookshelf#bookstagram#bookworm#bookaholic#bookaddict#book review#bookreader#bookblogger#bookblr#booklover#bookofthemonth#bookgeek#bookgram

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Acceptance by Jeff Vandermeer

The conclusion. Where it all ends. But like the Smashing Pumpkins song, the end is the beginning is the end.

The final installment of the Southern Reach Trilogy, Acceptance, is stylistically different than its predecessors and attempts to tie up as many loose ends as possible. And by “as possible” I mean as many as the story wishes because frankly, the story itself is as organic and self-defining as Area X.

Stylistically speaking, the past volumes dealt with a singular point-of-view throughout their entirety, while Acceptance switches between four different characters at different points of time. Some chapters happen before Area X was established while others are in the present within the story.

This helps explain some things about characters who may or may not be with us any longer, but there are sections which feel drawn-out for no good reason. One such part goes at length to describe the love life of one character in particular and feels weird and unnecessary within the story.

From there, the setting is as varied as the points of view and feels like a combination of the previous entries, Annihilation and Authority. Annihilation was set within Area X, Authority was set in the Southern Reach facility, and Acceptance takes place in both, again, across the different timelines.

And this dichotomy of environments makes the strangeness of both worlds more realized, and necessary to understand the other. It’s like both worlds form around each other like a jigsaw puzzle. Neither intruding on the other, but they both define the other.

Finally, the book was just really fun, and the trilogy was awesome. Science-fiction never felt more strange, and the lack of an antagonist breathes life into the mystery of the trilogy.

Is Area X the villain? Is the Southern Reach nothing but a hive of rogues? Is there really a bad guy, and if there is not, is one necessary for a good story to work? Or is a sense of dread good enough to hold the audience in place?

As in the previous entries, good luck deciphering an answer. You’ll be working it out in your head for some time. I know I still am.

4/5 cups of coffee

#the-bookist#Acceptance#authority#annihilation#Area X#southern reach#trilogy#Jeff Vandermeer#review#fiction#scifi#science fiction#science-fiction#sciencefiction#expedition#Unknown#books#book#bookworm#bookshelf#bookstagram#literature#bookblr#coffee#bookaddict#bookoholic#bookoftheday

72 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Authority by Jeff Vandermeer

Oh, so you read Annihilation and liked it but were left wanting more? More answers mayhaps? Or more beautiful prose and descriptions of a strange yet natural environment? Well, sucks to suck.

The second entry into the Southern Reach Trilogy, Authority, offers few answers about what happened in Annihilation, and takes us completely out of the beautiful horror that is Area X altogether.

While the first book painted a picture of Area X as both foreign and familiar, the setting of Authority is within an office building, which is also painted as both foreign and familiar but for different reasons.

You could say the office environment is more alien than anything Area X had to offer. The offices of the Southern Reach are subversive to everything you think of as natural to an office environment while there is always some level of mystery to the uninhabited, natural world.

There are definitely parallels to be drawn between the two environments and settings, but ultimately they are products of the same mystery and question of what the hell Area X is or what it wants.

Beyond the setting and the mysteries of office life, we are left questioning almost everything from the first book.

Did the people in the first book really die like we were told? If not then what the fuck happened to them? Was the biologist hallucinating the whole thing? Is she still hallucinating? Where do our new main character’s, including a man who goes by Control for reasons a psychology undergrad would say have to do with his desire to exert control over the situation at the Southern Reach facility, allegiances lie? With themselves, the Southern Reach, or some other vague entity?

The best way to describe the second entry in the trilogy is an enigma wrapped in a conundrum enfolded in paradox, to borrow an old cliche.

And by some miraculous feat, the book pulls it off. It doesn’t feel convoluted or full of itself and comes off as organic, pun intended.

The office-style power struggles, the navigation of mundane meetings, and the rifling through of paperwork is all too familiar to anyone who has worked in an office and it all feels real. Even though it might not be.

The mystery of Area X is heightened in Authority, but we start to learn the barrier of Area X doesn’t keep the unnatural nature in containment. The barrier reflects the unnatural nature all around us.

4/5 cups of coffee

#the-bookist#authority#jeff vandermeer#review#southern reach#trilogy#Annihilation#Area X#weird fiction#fiction#scifi#science fiction#science-fiction#sciencefiction#expedition#unknown#books#bookshelf#bookworm#bookaholic#bookaddict#scienceetfiction#books and libraries#bookstagram#bookblr#literature#coffee

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Annihilation by Jeff Vandermeer

You want to get trippy? Let’s get fucking trippy.

If you want to have your brain shaken, liquified, and then have it slowly drip out of your nostrils, pick up Jeff Vandermeer’s first book in his Southern Reach Trilogy titled Annihilation.

The book follows an unnamed biologist and three other women who are tasked with exploring Area X, a landscape that was transformed years ago, for reasons we never find out, into a mysteriously primordial environment where new world technology seemingly doesn’t work and the creatures which previously inhabited the area are monstrous versions of themselves. Or maybe they are just perceived as monstrous…

While the group of women explore the weird environment, we get glimpses of the biologist’s past before the expedition. The brunt of these flashbacks concern how her husband was on the previous expedition, came back a husk of his former self (as most of the people who come back from these expeditions return, if they return at all), and died of cancer.

She wants to go on the expedition to try and understand what happened to her husband, and in a not so surface level way, to grieve her husband and his death.

The book is so strange slow burn of a read that it is hard to put down, and the unreliability of the narrator adds to the atmosphere of unease. And her unreliability is only buttressed by the fact that the organization, the aforementioned Southern Reach, which sent them into Area X has not provided the expeditions with any answers as to what they are really doing in Area X.

Are these things actually happening? Is it all in the biologist’s head? Is anything she has said, or anything provided by Southern Reach, real? None of these questions are answered, but if they were, it would be a disservice to the uncanny air of Area X.

Nothing is solved. Nothing is answered. Nothing makes sense. But everything is gorgeous, and maybe that’s the point. We will have to wait and see in the second book of the trilogy.

4.5/5 cups of coffee

#the-bookist#Annihilation#jeff vandermeer#review#southern reach#trilogy#Area X#weird fiction#fiction#science fiction#expedition#unknown#coffee#books#bookworm#bookshelf#bookaholic#bookaddict#books and libraries#bookstagram#bookblr#literature

320 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ta-Nehisi Coates is writing Captain America and we should all be excited Earlier this week, writer and journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates announced in an article for the Atlantic he would take on writing the next iteration of Captain America as well as continuing to write Black Panther. Coates as a writer for one of the most recognizable Marvel characters makes perfect sense, and the two together, I am confident, will make some thought provoking comics. To understand this though, first we have to do a quick recap of who Captain America is. In comic book lore, Captain America is the peak of patriotism. While there are other national-symbol heroes such as Guardian (Canada) and Captain Britain (Britain, duh, but wouldn’t it be ironic if he was India’s national superhero?), none quite measure up to Captain America. Thanks to the Marvel movies, everyone knows his backstory by this point. A tough as nails, scrawny kid from Brooklyn who undergoes an experiment to become a super soldier to fight in World War II. The experiment goes well, Steve becomes super-strong, has super-human reflexes, and is super-resilient amongst other abilities, and he goes on to help the Allies win WWII by taking on Red Skull and famously punching Hitler. From Brooklyn, tough, kicking the asses of Nazis and others who prey on the downtrodden? Yeah, that’s pretty American. After WWII ends, the story of Captain America gets a little muddied. Some storylines have the captain retiring for a few years while others, and as far was the movie storyline goes, see him frozen in a state of suspended animation and then thawed out later in the century. Either way, Captain America is inactive for years after the fall of Nazi Germany. Rogers fights communists for a bit, but for a long time he never faces off against a real world scourge such as the Nazis. So in place of fighting horrible human-beings, which Nazis obviously are, the writers got experimental, and one storyline sees Rogers abandon the Captain America moniker. He says he can no longer serve his country after finding out the president (heavily hinted at being Richard Nixon) was the leader of a terrorist organization. This storyline was short-lived as Rogers returns to be Captain America after a few issues, but it perfectly exemplifies who Rogers is and what he stands for. He isn’t blindly loyal to America out of some sense that if it’s American it must be right, but he is loyal to the dream of what America can and should be. And it is this reason why Ta-Nehisi Coates will be a fantastic writer for Captain America. Coates is not a person who thinks America can do no wrong, and he has actively spoken out against people who hold this mentality. He knows America can be oppressive towards groups of people and he knows we as a country can do better. And in that regards, Coates and Rogers share a common mentality. They both know what America can and should be and neither of them are afraid to give up on these ideals. They both fight for the victimized of society because both have been victims in one sense or another. Beyond that, our current cultural environment is ripe for stories concerning the downtrodden. Within the last week alone, the US Supreme Court passed a ruling that immigrants, no matter what their legal status, can be held in detention indefinitely. And this ruling doesn’t hold a candle to attention the Black Lives Matter movement over the past few years has garnered. Will we see Captain America abandon the name again and resume being Nomad under Coates? Possibly. Will Coates take Captain America in a direction most people don’t agree with on a political level? Probably. Will the two reflect off of each other and make us think about what America really means? Absolutely.

0 notes

Photo

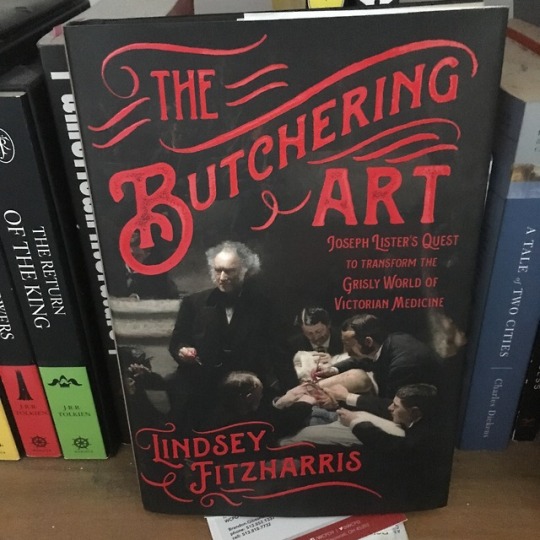

The Butchering Art: Joseph Lister's Quest to Transform the Grisly World of Victorian Medicine by Lindsey Fitzharris

Grisly and gory is putting medical practices in the Victorian era gently, and Lindsey Fitzharris gives us a look at the catalyst which brought medicine into the modern, pre-computer, age.

The Butchering Art: Joseph Lister’s Quest to Transform the Grisly World of Victorian Medicine is just that, a quest of how Lister went from the son of a Quaker on the verge of giving medicine up altogether, to becoming responsible for saving billions of lives for years to come with his development of antiseptic methods for doctors and surgeons.

Lister was a sort of maverick in the medical world at the time. While other doctors, if they can be called that, prescribed similar methods of treatment you might hear from your grandmother or other sources of superstition, Lister attempted to understand what made people sick and quantified the results of his prescribed methods.

Lister found the key to understanding illnesses in something considered a toy at the time. The microscope was seen as a novelty made for entertainment rather than serious learning. Lister saw the potential of the toy and used it to analyze samples of tissue, blood, and other naturally occurring materials to help push the idea that there were small organisms which made people sick i.e. germ theory.

Others laughed at Lister. I mean, small organisms making people sick? Poppy-cock I say! Everyone knows people get sick from weird smelly air! No really, people thought bad smelling air was a cause of illness.

Lister faced a lot of pushback at the time, but history shows that ultimately Lister’s methods were accepted and celebrated beyond his wildest dreams.

By the end of the book, you see how strange medicine used to be and how far it has come. From a competition of one-upmanship and who had the “better” method, to science! All science, all the time!

With this in mind, the book itself is full of medical terms and practices and different diseases. It is certainly interesting, but at the same time about as exciting as reading a book about medicine. Everyone can learn something, but unless medicine is something you are inherently interested in, you won’t be chomping at the bit by any means.

2.5/5 cups of coffee

#the-bookist#The Butchering Art#Joseph Lister#lindsey fitzharris#review#medicine#Victorian#surgery#antiseptic#coffee#bookworm#books#bookshelf#bookaholic#bookaddict#bookstagram#nonfiction#life-saving

115 notes

·

View notes