#aramaic poetry

Text

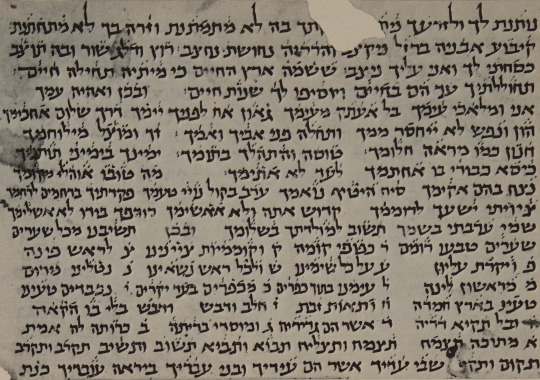

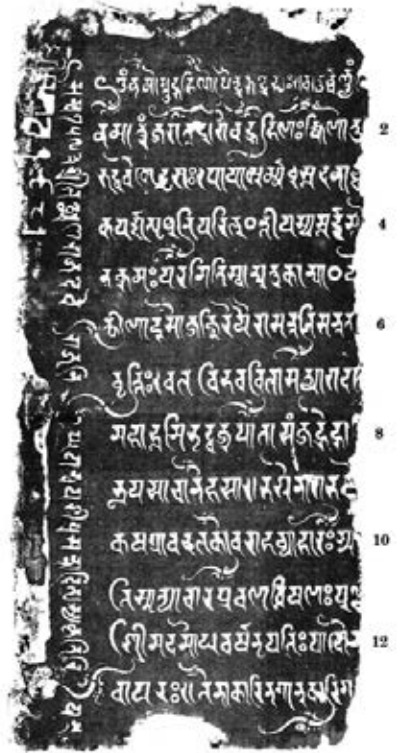

The Book of Job chapter 6

Job offers a rebuttal

So Job is not nearly as angry with Eliphaz as I was. I guess Job is too tired to be angry. Instead he disputes the notion that G-d will punish him for what he's saying. He's already destroyed. What is G-d going to do to him? Killing him would be a mercy at this point.

I would be much less poetic to the "happy is the man who God reproves". Certainly I wouldn't be talking about calamity heavier than the sands on the sea and arrows of the Almighty in me.

This might prove more difficult than I thought. There's a LOT of great poetry in this book (even in the not terribly poetic JPS translation). I am reminded of my Theater History class in college where we got to Hamlet and everyone just started talking about how much they loved the poetry. Like every other work we could talk about themes, characters, staging, etc. But Hamlet just hypnotized everyone and the professor noted that almost every class has very little to say about Hamlet when they are first introduced. Which is weird since there is way MORE to say about Hamlet than Oedipus Rex or the Revenger's Tale.

His words go from general to specific. He notes that only the suffering cry out. Then goes back to the "If only God would destroy me" before pointing out that his friends are useless. Worse than useless. Sure first he compares them to melting ice, but then he goes "do you devise words of reproof but count a hopeless man's words as wind? You would even cast lots over an opran, or barter away your friend."

But continually he is going "tell me that I'm wrong"

So this is getting long, but today I was reminded of a particular noxious individual that I considered a friend before Obama won and then still considered a friend until the fact that every time I said hello he just glared at me. I later learned that he told mutual friends about how much he hated me. He was always a creepy dude so I wasn't terribly concerned about him cutting ties with me, but he founded a publishing company and his family still runs it so it's annoying that he publishes some cool Jewish books that I would love to buy if I wasn't giving that mamzer money.

Anyhow on the way home, I looked him up to see what he's been doing. Jumping from job to job. Had a time as a pulpit rabbi (left after a year so probably molesting some congregants) and a lot of articles about how abortion is murder complete with taking that Project Veritas "abortion" video at face value.

I found his LinkedIn account (I swear it only took 10 minutes to look all this stuff up) and saw that he responded to a post about how "Man, that's tough" being a good thing to say to someone being overwhelmed with a bitchy self-aggrandizing post about how he needs PRACTICAL ADVICE when he's feeling overhwhelmed. He even said that he's playing devil's advocate.

So I told him that he sounds like Eliphaz the Temanite (he's a rabbi so he should get the reference) and that I have advice for him, stop being a noxious lying little shit.

I'm not proud of myself for that.

But it's fascinating to see that this guy (who also used to post articles on Facebook about how you should be EMOTIONALLY STRONG) is still about as knowledgeable about human emotions as he was back when he was the glaring asshole of Washington Heights.

Oh shit. It's not even about him. It's about another friend who just sent me an email inviting me to her philosophy group at Columbia. We haven't talked since she went off the deep end stanning for the CCP.

Oh. Damn.

Anyhow. Job is wondering why his friends have nothing to help him beyond reproof and bullshit statements like "happy is the man who God reproves" And as a reader, I'm wondering why these guys are acting that way.

But I miss a friend and because I can't really talk to her and there's really no way I see us ever being friends again, I look up a shitty dude that I never liked that much in the first place.

Can you believe I write term papers for a living? One thing I have over ChatGPT is the fact that I'll never start throwing in these personal asides.

#The Book of Job#CCP#Alec Goldstein#Tim Lieder#dumbshits#depression#sadness#The Bible#Bible#arrows of God#metaphors#poetry#JPS#aramaic poetry#probably better in the aramaic#would you sell out a friend#toxic positivity#psychology#bad friends#good friends without empathy#empathy#suffering#dead children#death

1 note

·

View note

Text

So many busy tongues, they are like an ocean

washing me this way and that, like a piece of seaweed--

Do your worst!

Trixie Te Arama Menzies, Ocean of tongues

#Trixie Te Arama Menzies#Ocean of tongues#Puna Wai Korero#busy tongues#rumours#rumors#gossip#talking#seaweed#Maori poetry#Indigenous literature#poetry#poetry quotes#quotes#quotes blog#literary quotes#literature quotes#literature#book quotes#books#words#text#do your worst

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good Enough

Pairing: Edwin Payne/Charles Rowland

Rating: T

Word Count: 4.000

Read on AO3

So, Edwin is in love with him.

Edwin loves him, and Charles genuinely never even considered the possibility of this, of them, before.

It might be because, back when he was still alive, his dad would have beaten the notion right out of him, but then again, his dad has been wrong about most things in his life, so fuck him.

So, Edwin is in love with him.

It’s… quite flattering, actually. To think that Edwin, who is beautiful and intelligent and educated, who can recite his favourite Keats poem by heart just as easily as tell you his favourite Mozart aria (it’s Konstanze, dich wiederzusehen from Die Entführung aus dem Serail, Edwin told him that, years ago), who knows spells and can read ancient Aramaic, who is the kindest, most brilliant person Charles has ever known, would love him.

Now, Charles knows that he is easy enough on the eyes, good with words and people, and has one hell of a swing if you give him a cricket bat, but the only reason he knows any Mozart aria is because Edwin showed them to him.

The only reason he knows Keats’ poetry is because Edwin would read them to him on slow, warm summer nights in the early 2000s.

The only reason he is here, is because Edwin let him stay.

So, it’s special, having someone like Edwin love him.

It’s fucking terrifying.

Because Charles is now holding the heart of the person he loves most in the world, and it’s a bigger responsibility than any he has ever taken on before.

He can’t fuck this up.

The thing is that nothing changes between them at all.

Charles isn’t sure if he expected it to, but what he is relatively certain about is that it most likely should. After all, it was an unexpected revelation, probably to both of them, definitely a shift in their relationship.

And yet, when Charles looks at Edwin, who is reading a novel whose name he cannot make out, curled up on the couch they have gotten for Crystal (and sometimes Jenny), he doesn’t feel different at all.

It’s still Edwin, his best mate, the boy that read to him when he was dying so he wouldn’t have to do it alone, who tries to smile whenever Charles shows him a new song he has fallen in love with, and occasionally fails hilariously at, who Charles would protect with his life and his soul and his cricket bat, no matter how high the stakes.

I love you the most, Charles thinks to himself, and smiles, because nothing about that has changed, either.

He has told Edwin that they would have forever to figure out the rest, and it’s the truth, technically speaking.

However, Charles doesn’t, because it’s Edwin and he has given Charles his heart and he doesn’t deserve to wait that long for an answer. It would be cruel in a way Charles cannot comprehend, and if there is anyone who doesn’t deserve more cruelty in their existence, it’s Edwin Payne.

The only problem with that fact is that Charles doesn’t know the answer.

He’s been thinking about it a lot, but the thing is, he’s never been in love before.

So he doesn’t really know what to compare his feelings for Edwin to, because, of course, they are greater than for anyone else, of course, Charles would sacrifice anything and anyone for Edwin, especially himself, of course, making Edwin smile is his favourite part of any day.

Because he loves Edwin, everything about him.

But is he, could he be, in love with Edwin?

Charles doesn’t know, nor does he know how to find out. It’s not like he hasn’t tried, but every novel he has paged through, every silly romcom he has watched, has been talking about butterflies in someone’s stomach, of seeing them in some new, golden light, of hearing violins playing when they speak, and Charles very much doubts that Edwin feels any of those things for him.

Otherwise he wouldn’t raise his eyebrows like that when he thinks Charles is being an insufferable little prick, he wouldn’t roll his eyes and tell him, “I know, Charles, you have told me a thousand times before”, whenever Charles brings up how much he wishes he could still taste things, or groan whenever Charles attempts to convince him to just try and let him put on some eyeliner.

(It’s just that Edwin would look so pretty like that, some kohl to bring out the warmth of his eyes, making them stand out even more than they do anyway.)

So all this talk of violins and sparkles and the need to give someone roses, if Edwin doesn’t feel that when he says he is love with Charles, then it’s pointless to consider, and anyway, those books and films describe people who have just met, not those who have known each other for twice as long as they were alive.

Maybe if he had just met Edwin, he would be hearing violins, Charles definitely thinks it’s possible.

Especially the violins in Konstanze, dich wiederzusehen.

“I just need some time alone”, Crystal says, putting on her jacket, while already opening the door. “And I am aware that that is a novel concept for the two of you, since you are basically attached at the hip, but for me, an alive human being, it’s really important to occasionally have a second of peace between almost dying and whatever we will have going on next.”

She stops to put on her shoes, almost falling over in the process, and Charles and Edwin share a look, a smile, and Charles thinks, I love you the most.

“Don’t follow me”, Crystal tells them, especially Charles, and it’s kind of cute, actually. “I’m going to get the biggest frappuchino Starbucks is legally allowed to serve me and I will not tolerate any ghostly company while doing that.”

Charles holds up his hands, still grinning, indicating his surrender in a battle he wasn’t aware they were fighting, and Crystal gives him a single nod before she walks out.

“So”, Charles starts, and turns around to face Edwin, who is already looking back, “what do we think this frappuchino she was talking about, is?”

Actually, there is one thing that changes between them after all.

It’s subtle, at least at first, but looking back, Charles isn’t quite sure how he managed to miss it for the few weeks that have passed. Maybe it was the shock of almost being forced to move on to the afterlife, the chaos of getting Crystal and Jenny settled in London, the fact that it seems to increase only slowly, incrementally.

Edwin has never been a physically affectionate person, completely contrary to how Charles is.

If it had been up to him alone, he would have hugged Edwin much more often, would have leant against him when they were looking through a book together, would have held hands to keep them from losing each other when things got hectic. But it wasn’t, and that was fine, so it was occasional touches instead, a hand on Edwin’s upper arm, his back, ruffling his perfect hair when he was doing something kind of dumb, kind of cute.

(That one always made him duck his head and smile, glance up at Charles through his lashes and allow a second to pass before he started fixing his hair again.)

Now, however, it’s… it’s not getting better, because there was nothing wrong with it in the first place, Edwin’s aversion to physical affection, but it is changing now.

It’s less that he initiates it, more than he allows it to happen more frequently. Sitting down next to Charles on the sofa instead of taking the armchair, allowing Charles’ hand to linger on his arm for a moment longer than expected, letting their shoulders brush when walking.

He’s not asking to be touched, not really, but something about it still makes Charles irrationally happy as soon as he catches onto it. Because Edwin deserves all the affection the world can offer, and Charles will always be here to give it to him.

So he reaches out in the morning, when the sun has just started to rise, and puts his hand on the curve of Edwin’s shoulder, right where it meets his neck, and points out that the clouds are turning the most beautiful pink. He throws his legs across Edwin’s lap when they settle down on the sofa at night, a book in Edwin’s hands, the tablet Crystal made him buy in Charles’. He pushes his fingers through Edwin’s hair, not to ruffle it, but just to pretend he can feel its softness against his skin.

It makes Edwin duck his head again, give Charles a little smile when looking up, and Charles thinks, I love you the most.

And thinks, I want to love you the most in every way you will have me.

“Jenny, I have a question”, Charles starts as soon as he has phased through the walls of her new butcher shop. It’s to her credit that she hardly reacts; the first time he had done that, she had thrown a meat cleaver right through his head. “What do you know about love?”

Instead of a knife, Jenny just throws him a weary look, an eyebrow elegantly arched. It makes Charles think of being scolded by the headmistress, a sensation that should be much more unpleasant than it is.

“Nothing”, Jenny answers and brings her cleaver down with a dull thud, separating flesh from bone, before looking up at Charles again. “No one ever knows anything about love and if they try to tell you otherwise, they are lying.”

There is a certain sense of finality in her voice and Charles knows he has been dismissed, no detention this time, but don’t dare to push it.

“Great”, he mutters, more to himself than to Jenny, “that doesn’t help me at all.”

“You should look at this, Charles”, Edwin says and turns the book towards him.

It’s late at night, Crystal having long since gone home and they are sat on the sofa, shoulders touching while they do their research. A new case has come up, and Edwin is trying to learn more about ancient Celtic runes, while Charles is pouring over a map of London’s underground; now, he looks up and at the page Edwin is showing him.

“We could add this to your bat”, Edwin explains, “it’s a rune for physical strength. Supposedly, it doubles whatever force you put into a hit.”

“Edwin, mate, are you trying to tell me I need help with hitting people?”

Charles is grinning, obviously teasing, and Edwin just scoffs, rolls his eyes.

And that is what Charles means; this isn’t birdsong and candle light, this is just how they always have been. This is what makes them them, even.

“Charles, do be serious”, Edwin replies, but there is affection in his voice, there is love. “I am perfectly aware that you can hit things very well, but that doesn’t mean that hitting them even better wouldn’t be an advantage.”

“I know. This is brills”, Charles concedes, and on a whim, nothing more than that, presses a quick kiss to Edwin’s cheek.

For a moment, he almost expects Edwin to admonish him, because this isn’t exactly something that they do, but instead he stares at him, before he ducks his head; Charles isn’t sure how he knows this, but if Edwin could, he would be blushing.

And it does something to Charles’ head, the thought that he would be able to make Edwin blush. It makes him stop dead in his tracks, look at Edwin not like he is seeing him for the first time, but like he could be looking at him for the rest of his existence and not get bored of it.

“Do you wanna do the honours of carving it? Since you were the one who found the thing?”, he asks just to say something, aware that his voice sounds slightly off, and thinks, I love you the most. I love you the most. I love you the most.

“Very well done, Charles”, Edwin tells him and clasps a long-fingered hand on Charles’ shoulder, peering down at the leprechaun he knocked out clean with his bat a few seconds before.

The rune really makes it pack a punch.

“I don’t think this will pose any further problems”, Edwin continues even as he crouches down to examine the passed-out form crumpled on the ground. He prods at it gently.

“It fucking better”, Charles replies, resisting the urge to pull Edwin away from the leprechaun, just in case that touching it might have some kind of magical side effect. “And if not, I’ll punch it right back out. I’ve got an Edwin Payne-improved bat after all, it won’t stand a chance.”

Just for good measure, he twirls the bat around once, twice.

This has always been one of his favourite parts of the job, the simple pleasure of knocking someone out before they get the chance to hurt his friends.

Edwin looks up at him from where he is crouching, and Charles grins at him, metaphorical adrenaline running through his non-existent veins still. He would punch out a bear if Edwin asked it of him.

Before he can say anything else, though, Crystal clears her throat from behind him, sounding decidedly less impressed.

“That’s really cool, yeah. New bat, I get it”, she says, walking around Charles so she, too, can see the unconscious leprechaun. “But you do remember that we actually wanted to talk to him, right?”

They get to talk to the leprechaun in the end, who turns out to be about as obnoxious as expected, but does admit to stealing the heirloom they were looking for for his pot of gold.

He even gives it back, but only after Charles has started twirling his bat again.

“And another satisfied customer”, Charles comments as they return to the agency, flinging his backpack into the corner.

“Client, you mean”, Edwin corrects, but still smiles at him, and pats the space next to him as soon as he sits down on the sofa. Charles flings himself down without a second thought, legs landing somewhere across Edwin’s laps, one of his hands settling on Charles’ ankles.

This is new, at least to some extent, and Charles loves it, the feeling of Edwin’s fingers on him. It feels right, somehow.

I just really love you the most, he thinks.

“Yeah, whatever”, he concedes and looks over at Crystal, who is watching them with something in her eyes that Charles cannot quite place. Not bad, per se, just…. Strange. “Doesn’t sound that good though, does it? And anyway, the most important thing is that they’re satisfied, right? Passed on right to the afterlife, no worries keeping them here any longer.”

“As if it’s only worries that could keep one here”, Edwin replies, his tone as dry as the desert, but making Charles laugh anyway. “We should be the best example for that.”

“You know what I mean!”, he shoots back, “It isn’t like with us, is it? Don’t think that the client was kept back by meeting the love of their life, were they now?”

It spills from his lips like nothing, without Charles thinking about it for a single second.

He’s still laughing, but Edwin’s fingers have stopped where they were gently stroking across the arch of his foot, and then Charles realises it, and for the first time, hears silence.

For the first time since they got back from Hell, they part when Crystal leaves.

The conversation had been stilted after Charles’...slip up? blunder? confession? and although it had been obvious that all three of them had been trying, it had been impossible to get things back on track.

So, Charles leaves with Crystal, telling Edwin he will walk her home, although that is something he has never done before, and Crystal lets him, although he is fairly certain she wouldn’t under normal circumstances.

She doesn’t need anyone protecting her from the city she grew up in after all.

“How do you know you’re in love with someone?”, Charles asks after they have walked in silence for a few minutes. He can’t think of a way to cushion the question, how to make it less awkward to ask, so he doesn’t bother with it at all.

“This is about Edwin?”, she asks, seemingly to clarify, and Charles nods mutely, not looking up at her. “I’m not sure. Especially not when it comes to the two of you. For Edwin, I could have seen from miles away that he was in love with you, even if he hadn’t reacted like he did when we first met. For you… you love him, anyone with eyes could see that, but if you’re in love with him, I think you have to figure that out yourself.”

“Do you know how it feels, though? Being in love?”, he asks, just in case Crystal can at least tell him that.

“I’m not sure”, she answers after a moment, then links their arms together, pulling Charles closer. “I think that’s different for everyone. But I’m sure you’ll be able to figure out what it feels like to you if you let yourself.”

He walks Crystal home, but when she asks if he wants to stay, Charles just shakes his head.

Edwin is back at the agency, and Charles isn’t sure exactly in which state, what he is thinking, and Charles cannot allow that. At least not for long.

What he does, though, is taking a little detour to the park not too far from their building.

It’s the first time he really pays it any mind, even if it’s most likely not the first time he’s been there, but now, Charles lays down on the grass, looking up at the night sky.

London is too bright for him to see many stars, but there’s a few of them; Edwin would surely be able to point out a constellation or two.

And that’s the thing, isn’t it.

Edwin isn’t here, and yet he is with Charles anyway, always, in every moment of his existence.

Sighing, he scrubs a hand down his face. There’s no way around it, it has to be now, and it has to be the right answer, the one he truly means, because Edwin deserves nothing but that.

No false hope, and no heartbreak that might be taken back along the line.

So, he thinks of Edwin, of his elegant hands and the swagger in his walk when he feels confident, of the colour of his hair and of his eyes, of the curves and slopes and sharp cuts of his face.

He loves that face, has seen it with every possible expression painted across of it, and still loves it.

The stars above are dim and partly hidden behind the clouds, so Charles lets his eyes slip shut, and imagines coming home to the agency and taking Edwin’s hands in his.

They would be just a little smaller than his own, his fingers slender and yet so capable, and if he could still feel, Charles is convinced they would feel cool against his skin.

He imagines pulling Edwin close and holding him like he has always wanted to, burying his face against the side of Edwin’s neck and pretending he can breathe in his scent. Having Edwin sneak his arms around Charles’ waist and cling to the back of his jacket, like he doesn’t want to let go again.

In his imagination, it feels a little like the hug they shared after being granted asylum on Earth, but it would be entirely different, because it wouldn’t be out of relief.

Instead, it would be just them, embracing to feel the other close.

And he thinks of pulling back from the hug, seeing Edwin smile and kissing the curve of his lips, nipping at them until he can make Edwin laugh and teasing his mouth open to lick into it.

It would be like kissing Crystal, kind of, only that-

Only that it wouldn’t be like that at all.

He runs back to the agency, as fast as his spectral feet can carry him.

Edwin is sitting right where he left him, almost like he hadn’t moved an inch since Charles walked out of the door, and he hopes to all deities he can think of that it isn’t so; knows, at the same time, that it is.

“Hi”, Charles greets, because he doesn’t know what else to say, and Edwin nods and gives him a smile, brittle and unsure and hopeful, all at once.

“Hello, Charles. Did Crystal get home safe?”, he asks, and it’s so painfully polite it makes Charles cringe.

“Yeah. Yeah, sure, of course she did”, he responds, trying to figure out how to begin saying what he needs Edwin to know, but Edwin beats him to it.

“Did you mean it?”, Edwin asks, breathes out the question like he still has lungs to do so, and it’s in that moment that Charles is more certain of his answer than anything else he has ever thought, because Edwin sounds small, sounds vulnerable and breakable and yet so fucking hopeful, and Charles wants to pick him up and cradle him against his chest and never let go again.

“Yes”, he says, and it’s sunrise and violins and bouquets of roses all at once, it’s a single word that changes the world around them. “Kind of. Let me explain.”

And Edwin nods, sits back with his hands in his lap and all Charles can think about is that those same hands belong holding a book, resting on the top of Charles’ legs, which should be flung carelessly across Edwin’s lap, just because Charles wants to be near him.

“You’re the love of my life, no matter what”, he starts, crouching down in front of Edwin so he can take his hands; they look so lost. “You have been for decades. I love you the most of anything in the world. I will always love you the most. Every time I look at you, it’s just that on repeat in my head. I love you the most.”

He ducks his head, laughing softly, because it sounds silly now that he says it out-loud, but when he looks back up, there are tears brimming in Edwin’s eyes, making them shine even brighter.

His lips are parted and for just a moment, Charles thinks about kissing them.

“And you know, I still can’t say that I am in love with you back, because you don’t deserve a lie, but what I can say, what I can promise you, is that I could fall in love with you. And that I want to. More than anything.”

A single tear rolls down Edwin’s cheek, glistening in the dim light, and Charles looks at him, and thinks, I do. I am. I love you the most.

“Could that be enough?”, he asks, squeezing Edwin’s hands in his. “At least for the start?”

And Edwin nods so frantically that more tears spill over, wetting his face, and Charles can’t help but laugh; how strange to think that making Edwin cry for once is not his biggest fear, but something that fills his heart with joy to the point of bursting.

“Okay. Brills, that’s-”, he replies, and can’t keep himself from smiling so wide it would hurt if he was still alive. “So, um. Can I kiss you? I really want to kiss you right now.”

Again, Edwin nods, and he is smiling, too, looks so happy that Charles thinks heaven must be overrated, because nothing in the whole of existence could compare to this.

He thinks of the scene he pictured in the park of holding Edwin close and how much in pales in comparison to this, to holding Edwin’s hands and watching him glow with love and hope and warmth.

And leans in to find out if the same is true for kissing him.

(It is.)

#dead boy detectives#dead boy detective agency#dbd#edwin payne#edwin paine#charles rowland#painland#payneland#paynland#chedwin#charles x edwin#edwin x charles#i have written 10k for them now it has been 4 days since i watched the show#what is happening

329 notes

·

View notes

Text

The most important deity you've never heard of: the 3000 years long history of Nanaya

Being a major deity is not necessarily a guarantee of being remembered. Nanaya survived for longer than any other Mesopotamian deity, spread further away from her original home than any of her peers, and even briefly competed with both Buddha and Jesus for relevance. At the same time, even in scholarship she is often treated as unworthy of study. She has no popculture presence save for an atrocious, ill-informed SCP story which can’t get the most basic details right. Her claims to fame include starring in fairly explicit love poetry and appearing where nobody would expect her. Therefore, she is the ideal topic to discuss on this blog.

This is actually the longest article I published here, the culmination of over two years of research. By now, the overwhelming majority of Nanaya-related articles on wikipedia are my work, and what you can find under the cut is essentially a synthesis of what I have learned while getting there. I hope you will enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed working on it.

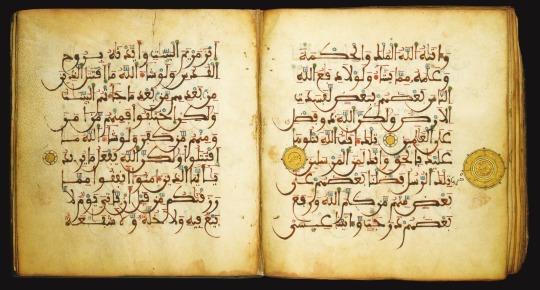

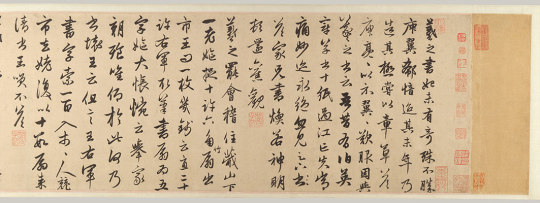

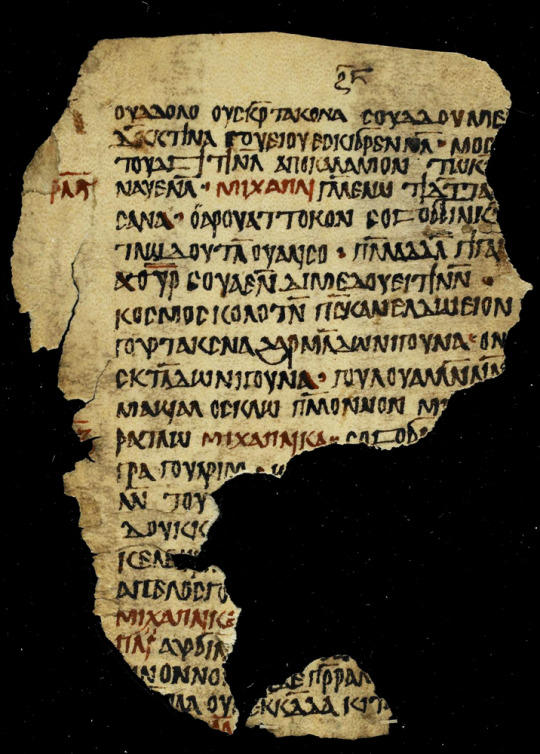

Under the cut, you will learn everything there is to know about Nanaya: her origin, character, connections with other Mesopotamian deities, her role in literature, her cult centers… Since her history does not end with cuneiform, naturally the later text corpora - Aramaic, Bactrian, Sogdian and even Chinese - are discussed too. The article concludes with a short explanation why I see the study of Nanaya as crucial.

Dubious origins and scribal wordplays: from na-na to Nanaya

Long ago Samuel Noah Kramer said that “history begins in Sumer”. While the core sentiment was not wrong in many regards, in this case it might actually begin in Akkad, specifically in Gasur, close to modern Kirkuk. The oldest possible attestation of Nanaya are personal names from this city with the element na-na, dated roughly to the reign of Naram-Sin of Akkad, so to around 2250 BCE. It’s not marked in the way names of deities in personal names would usually be, but this would not be an isolated case.

The evidence is ultimately mixed. On one hand, reduplicated names like Nana are not unusual in early Akkadian sources, and -ya can plausibly be explained as a hypocoristic suffix. On the other hand, there is not much evidence for Nanaya being worshiped specifically in the far northeast of Mesopotamia in other periods. Yet another issue is that there is seemingly no root nan- in Akkadian, at least in any attested words.

The main competing proposal is that Nanaya originally arose as a hypostasis of Inanna but eventually split off through metaphorical mitosis, like a few other goddesses did, for example Annunitum. This is not entirely implausible either, but ultimately direct evidence is lacking, and when Nanaya pops up for the first time in history she is clearly a distinct goddess.

There are a few other proposals regarding Nanaya’s origin, but they are considerably weaker. Elamite has the promising term nan, “day” or “morning”, but Nanaya is entirely absent from the Old Elamite sources you’d expect to find her in if Mesopotamians imported her from the east. Therefore, very few authors adhere to this view. The hypothesis that she was an Aramaic goddess in origin does not really work chronologically, since Aramaic is not attested in the third millennium BCE at all. The less said about attempts to connect her to anything “Proto-Indo-European”, the better.

Like many other names of deities, Nanaya’s was already a subject of etymological speculation in antiquity. A late annotated version of the Weidner god list, tablet BM 62741, preserves a scribe’s speculative attempt at deriving it from the basic meaning of the sign NA, “to call”, furnished with a feminine suffix, A. Needless to say, like other such examples of scribal speculation, some of which are closer to playful word play than linguistics, it is unlikely to reflect the actual origin of the name.

Early history: Shulgi-simti, Nanaya’s earliest recorded #1 fan

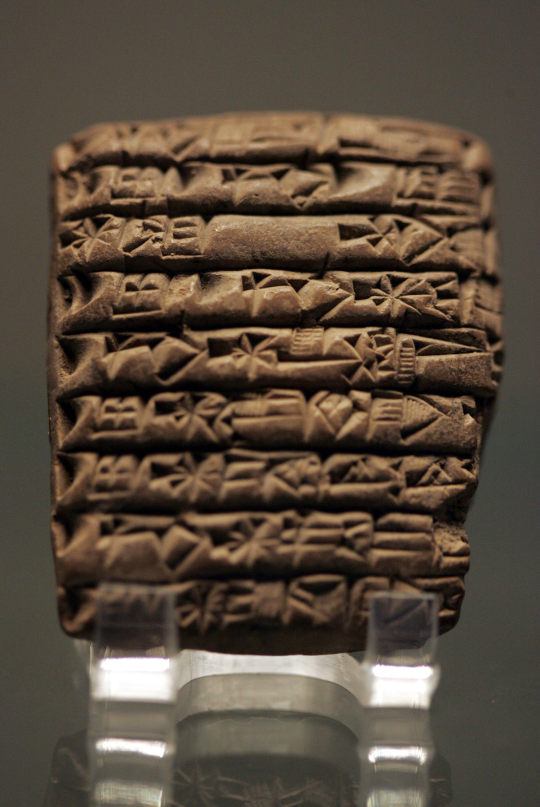

A typical Ur III administrative tablet listing offerings to various deities (wikimedia commons)

The first absolutely certain attestations of Nanaya, now firmly under her full name, have been identified in texts from the famous archive from Puzrish-Dagan, modern Drehem, dated to around 2100 BCE. Much can be written about this site, but here it will suffice to say that it was a center of the royal administration of the Third Dynasty of Ur ("Ur III") responsible for the distribution of sacrificial animals.

Nanaya appears there in a rather unique context - she was one of the deities whose cults were patronized by queen Shulgi-simti, one of the wives of Shulgi, the successor of the dynasty’s founder Ur-Namma.

We do not know much about Shulgi-simti as a person - she did not write any official inscriptions announcing her preferred foreign policy or letters to relatives or poetry or anything else that typically can be used to gain a glimpse into the personal lives of Mesopotamian royalty. We’re not really sure where she came from, though Eshnunna is often suggested as her hometown. We actually do not even know what her original name was, as it is assumed she only came to be known as Shulgi-simti after becoming a member of the royal family. Tonia Sharlach suggested that the absence of information about her personal life might indicate that she was a commoner, and that her marriage to Shulgi was not politically motivated

The one sphere of Shulgi-simti’s life which we are incredibly familiar with are her religious ventures. She evidently had an eye for minor, foreign or otherwise unusual goddesses, such as Belet-Terraban or Nanaya.

She apparently ran what Sharlach in her “biography” of her has characterized as a foundation. It was tasked with sponsoring various religious celebrations. Since Shulgi-simti seemingly had no estate to speak of, most of the relevant documents indicate she procured offerings from a variety of unexpected sources, including courtiers and other members of the royal family. The scale of her operations was tiny: while the more official religious organizations dealt with hundreds or thousands of sacrificial animals, up to fifty or even seventy thousand sheep and goats in the case of royal administration, the highest recorded number at her disposal seems to be eight oxen and fifty nine sheep.

A further peculiarity of the “foundation” is that apparently there was a huge turnover rate among the officials tasked with maintaining it. It seems nobody really lasted there for much more than four years. There are two possible explanations: either Shulgi-simti was unusually difficult to work with, or the position was not considered particularly prestigious and was, at the absolute best, viewed as a stepping stone.

While the Shulgi-simti texts are the earliest evidence for worship of Nanaya in the Ur III court, they are actually not isolated. When all the evidence from the reigns of Shulgi and his successors is summarized, it turns out that she quickly attained a prominent role, as she is among the twelve deities who received the most offerings. However, her worship was seemingly limited to Uruk (in her own sanctuary), Nippur (in the temple of Enlil, Ekur) and Ur. Granted, these were coincidentally three of the most important cities in the entire empire, so that’s a pretty solid early section of a divine resume. She chiefly appears in two types of ceremonies: these tied to the royal court, or these mostly performed by or for women. Notably, a festival involving lamentations (girrānum) was held in her honor in Uruk.

To understand Nanaya’s presence in the two aforementioned contexts, and by extension her persistence in Mesopotamian religion in later periods, we need to first look into her character.

The character of Nanaya: eroticism, kingship, and disputed astral ventures

Corona Borealis (wikimedia commons)

Nanaya’s character is reasonably well defined in primary sources, but surprisingly she was almost entirely ignored in scholarship quite recently. The first study of her which holds up to scrutiny is probably Joan Goodnick Westenholz’s article Nanaya, Lady of Mystery from 1997. The core issue is the alleged interchangeability of goddesses. From the early days of Assyriology basically up to the 1980s, Nanaya was held to be basically fully interchangeable with Inanna. This obviously put her in a tough spot. Still, over the course of the past three decades the overwhelming majority of studies came to recognize Nanaya as a distinct goddess worthy of study in her own right. You will still stumble upon the occasional “Nanaya is basically Inanna”, but now this is a minority position. Tragically it’s not extinct yet, most recently I’ve seen it in a monograph published earlier this year.

With these methodological and ideological issues out of the way, let’s actually look into Nanaya’s character, as promised by the title of this section. Her original role was that of a goddess of love. It is already attested for her at the dawn of her history, in the Ur III period. Her primary quality was described with a term rendered as ḫili in Sumerian and kuzbu in Akkadian. It can be variously translated as “charm”, “luxuriance”, “voluptuousness”, “sensuality” or “sexual attractiveness”. This characteristic was highlighted by her epithet bēlet kuzbi (“lady of kuzbu”) and by the name of her cella in the Eanna, Eḫilianna. The connection was so strong that this term appears basically in every single royal inscription praising her. She was also called bēlet râmi, “lady of love”. Nanaya’s role as a love goddess is often paired with describing her as a “joyful” or “charming” deity.

It needs to be stressed that Nanaya was by no metric the goddess of some abstract, cosmic love or anything like that. Love incantations and prayers related to love are quite common, and give us a solid glimpse into this matter. Nanaya’s range of activity in them is defined pretty directly: she deals with relationships (and by extension also with matters like one-sided crushes or arguments between spouses), romance and with strictly sexual matters. For an example of a hymn highlighting her qualifications when it comes to the last category, see here. The text is explicit, obviously.

We can go deeper, though. There is also an incantation whose incipit at first glance leaves little to imagination:

However, the translator, Giole Zisa, notes there is some debate over whether it’s actually about having sex with Nanaya or merely about invoking her (and other deities) while having sex with someone else. A distinct third possibility is that she’s not even properly invoked but that “oh, Nanaya” is simply an exclamation of excitement meant to fit the atmosphere, like a specialized version of the mainstay of modern erotica dialogue, “oh god”.

While this romantic and sexual aspect of Nanaya’s character is obviously impossible to overlook, this is not all there was to her. She was also associated with kingship, as already documented in the Ur III period. She was invoked during coronations and mourning of deceased kings. In the Old Babylonian period she was linked to investiture by rulers of newly independent Uruk.

A topic which has stirred some controversy in scholarship is Nanaya’s supposed astral role. Modern authors who try to present Nanaya as a Venus deity fall back on rather faulty reasoning, namely asserting that if Nanaya was associated with Inanna and Inanna personified Venus, clearly Nanaya did too. Of course, being associated with Inanna does not guarantee the same traits. Shaushka was associated with her so closely her name was written with the logogram representing her counterpart quite often, and lacked astral aspects altogether.

No primary sources which discuss Nanaya as a distinct, actively worshiped deity actually link her with Venus. If you stretch it you will find some tidbits like an entry in a dictionary prepared by the 10th century bishop Hasan bar Bahlul, who inexplicably asserted Nanaya was the Arabic name of the planet Venus. As you will see soon, there isn’t even a possibility that this reflected a relic of interpretatio graeca. The early Mandaean sources, many of which were written when at least remnants of ancient Mesopotamian religion were still extant, also do not link Nanaya with Venus. Despite at best ambivalent attitude towards Mesopotamian deities, they show remarkable attention to detail when it comes to listing their cult centers, and on top of that Mesopotamian astronomy had a considerable impact on Mandaeism, so there is no reason not to prioritize them, as far as I am concerned.

As far as the ancient Mesopotamian sources themselves go, the only astral object with a direct connection to Nanaya was Corona Borealis (BAL.TÉŠ.A, “Dignity”), as attested in the astronomical compendium MUL.APIN. Note that this is a work which assigns astral counterparts to virtually any deity possible, though, and there is no indication this was a major part of Nanaya’s character. Save for this single instance, she is entirely absent from astronomical texts.

A further astral possibility is that Nanaya was associated with the moon. The earliest evidence is highly ambiguous: in the Ur III period festivals held in her honor might have been tied to phases of the moon, while in the Old Babylonian period a sanctuary dedicated to her located in Larsa was known under the ceremonial name Eitida, “house of the month”. A poem in which looking at her is compared to looking at the moon is also known. That’s not all, though. Starting with the Old Babylonian period, she could also be compared with the sun. Possibly such comparisons were meant to present her as an astral deity, without necessarily identifying her with a specific astral body. Michael P. Streck and Nathan Wasserman suggest that it might be optimal to simply refer to her as a “luminous” deity in this context. However, as you will see later it nonetheless does seem she eventually came to be firmly associated both with the sun and the moon.

Last but not least, Nanaya occasionally displayed warlike traits. It’s hardly major in her case, and if you tried hard enough you could turn any deity into a war deity depending on your political goals, though. I’d also place the incantation which casts her as one of the deities responsible for keeping the demon Lamashtu at bay here.

Nanaya in art

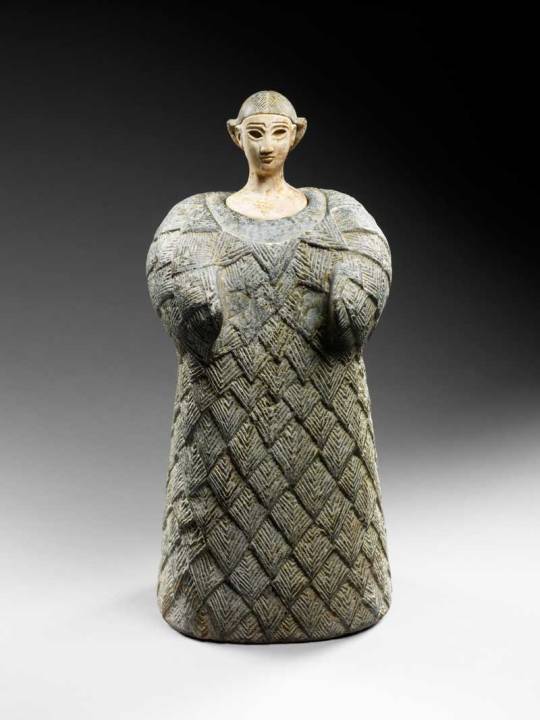

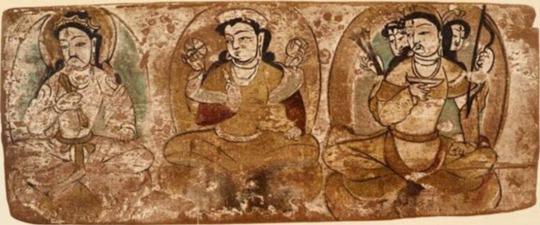

The oldest known depiction of Nanaya (wikimedia commons)

While Nanaya’s roles are pretty well defined, there surprisingly isn’t much to say about her iconography in Mesopotamian art.The oldest certain surviving depiction of her is rather indistinct: she’s wearing a tall headdress and a flounced robe. It dates to the late Kassite period (so roughly to 1200 BCE), and shows her alongside king Meli-Shipak (or maybe Meli-Shihu, reading remains uncertain) and his daughter Hunnubat-Nanaya. Nanaya is apparently invoked to guarantee that the prebend granted to the princess will be under divine protection. This is not really some unique prerogative of hers, perhaps she was just the most appropriate choice because Hunnubat-Nanaya’s name obviously reflects devotion to her.

The relief discussed above is actually the only depiction of Nanaya identified with certainty from before the Hellenistic period, surprisingly. We know that statues representing her existed, and it is hard to imagine that a popular, commonly worshiped deity was not depicted on objects like terracotta decorations and cylinder seals, but even if some of these were discovered, there’s no way to identify them with certainty. This is not unusual though, and ultimately there aren’t many Mesopotamian deities who can be identified in art without any ambiguity.

Nanaya in literature

As I highlighted in the section dealing with Nanaya’s character, she is reasonably well attested in love poetry. However, this is not the only genre in which she played a role.

A true testament to Nanaya’s prominence is a bilingual (Sumero-Akkadian) hymn composed in her honor in the first millennium BCE. It is written in the first person, and presents various other goddesses as her alternate identities. It is hardly unique, and similar compositions dedicated to Ishtar (Inanna), Gula, Ninurta and Marduk are also known.

Each strophe describes a different deity and location, but ends with Nanaya reasserting her actual identity with the words “still I am Nanaya”. Among the claimed identities included are both major goddesses in their own right (Inanna plus closely associated Annunitum and Ishara, Gula, Bau, Ninlil), goddesses relevant due to their spousal roles first and foremost (Damkina, Shala, Mammitum etc) and some truly unexpected, picks, the notoriously elusive personified rainbow Manzat being the prime example. Most of them had very little in common with Nanaya, so this might be less an attempt at syncretism, and more an elevation of her position through comparisons to those of other goddesses.

An additional possible literary curiosity is a poorly preserved myth which Wilfred G. Lambert referred to as “The murder of Anshar”. He argues that Nanaya is one of the two deities responsible for the eponymous act. I don't quite follow the logic, though: the goddess is actually named Ninamakalamma (“Lady mother of the land”), and her sole connection with Nanaya is that they occur in sequence in the unique god list from Sultantepe. Lambert saw this as a possible indication they are identical. There are no other attestations of this name, but ama kalamma does occur as an epithet of various goddesses, most notably Ninshubur. Given her juxtaposition with Nanaya in the Weidner god list - more on that later - wouldn’t it make more sense to assume it’s her? Due to obscurity of the text as far as I am aware nobody has questioned Lambert’s tentative proposal yet, though.

There isn’t much to say about the plot: Anshar, literally “whole heaven”, the father of Anu, presumably gets overthrown and might be subsequently killed. Something that needs to be stressed here to avoid misinterpretation: primordial deities such as Anshar were borderline irrelevant, and weren't really worshiped. They exist to fade away in myths and to be speculated about in elaborate lexical texts. There was no deposed cult of Anshar. Same goes for all the Tiamats and Enmesharras and so on.

Inanna and beyond: Nanaya and friends in Mesopotamian sources

Inanna on a cylinder seal from the second half of the third millennium BCE (wikimedia commons)

Of course, Nanaya’s single most important connection was that to Inanna, no matter if we are to accept the view that she was effectively a hypostasis gone rogue or not. The relationship between them could be represented in many different ways. Quite commonly she was understood as a courtier or protegee of Inanna. A hymn from the reign of Ishbi-Erra calls her the “ornament of Eanna” (Inanna’s main temple in Uruk) and states she was appointed by Inanna to her position. References to Inanna as Nanaya’s mother are also known, though they are rare, and might be metaphorical. To my best knowledge nothing changed since Olga Drewnowska-Rymarz’s monograph, in which she notes she only found three examples of texts preserving this tradition. I would personally abstain from trying to read too deep into it, given this scarcity.

Other traditions regarding Nanaya’s parentage are better attested. In multiple cases, she “borrows” Inanna’s conventional genealogy, and as a result is addressed as a daughter of Sin (Nanna), the moon god. However, she was never addressed as Inanna’s sister: it seems that in cases where Sin and Nanaya are connected, she effectively “usurps” Inanna’s own status as his daughter (and as the sister of Shamash, while at it). Alternatively, she could be viewed as a daughter of Anu.

Finally, there is a peculiar tradition which was the default in laments: in this case, Nanaya was described as a daughter of Urash. The name in this context does not refer to the wife of Anu, though. The deity meant is instead a small time farmer god from Dilbat. To my best knowledge no sources place Nanaya in the proximity of other members of Urash’s family, though some do specify she was his firstborn daughter. To my best knowledge Urash had at least two other children, Lagamal (“no mercy”, an underworld deity whose gender is a matter of debate) and Ipte-bitam (“he opened the house”, as you can probably guess a divine doorkeeper). Nanaya’s mother by extension would presumably be Urash’s wife Ninegal, the tutelary goddess of royal palaces. There is actually a ritual text listing these three together.

In the Weidner god list Nanaya appears after Ninshubur. Sadly, I found no evidence for a direct association between these two. For what it’s worth, they did share a highly specific role, that of a deity responsible for ordering around lamma. This term referred to a class of minor deities who can be understood as analogous to “guardian angels” in contemporary Christianity, except places and even deities had their own lamma too, not just people. Lamma can also be understood at once as a class of distinct minor deities, as the given name of individual members of it, and as a title of major deities. In an inscription of Gudea the main members of the official pantheon are addressed as “lamma of all nations”, by far one of my favorite collective terms of deities in Mesopotamian literature.

A second important aspect of the Weidner god list is placing Nanaya right in front of Bizilla. The two also appear side by side in some offering lists and in the astronomical compendium MUL.APIN, where they are curiously listed as members of the court of Enlil. It seems that like Nanaya, she was a goddess of love, which is presumably reflected by her name. It has been variously translated as “pleasing”, “loving” or as a derivative of the verb “to strip”. An argument can be made that Bizilla was to Nanaya what Nanaya was to Inanna. However, she also had a few roles of her own. Most notably, she was regarded as the sukkal of Ninlil. She may or may not also have had some sort of connection to Nungal, the goddess of prisons, though it remains a matter of debate if it’s really her or yet another, accidentally similarly named, goddess.

An indistinct Hurro-Hittite depiction of Ishara from the Yazilikaya sanctuary (wikimedia commons)

In love incantations, Nanaya belonged to an informal group which also included Inanna, Ishara, Kanisurra and Gazbaba. I do not think Inanna’s presence needs to be explained. Ishara had an independent connection with Inanna and was a multi-purpose deity to put it very lightly; in the realm of love she was particularly strongly connected with weddings and wedding nights. Kanisurra and Gazbaba warrant a bit more discussion, because they are arguably Nanaya’s supporting cast first and foremost.

Gazbaba is, at the core, seemingly simply the personification of kuzbu. Her name had pretty inconsistent orthography, and variants such as Kazba or Gazbaya can be found in primary sources too. The last of them pretty clearly reflects an attempt at making her name resemble Nanaya’s. Not much can be said about her individual character beyond the fact she was doubtlessly related to love and/or sex. She is described as the “grinning one” in an incantation which might be a sexual allusion too, seeing as such expressions are a mainstay of Akkadian erotic poetry.

Kanisurra would probably win the award for the fakest sounding Mesopotamian goddess, if such a competition existed. Her name most likely originated as a designation of the gate of the underworld, ganzer. Her default epithet was “lady of the witches” (bēlet kaššāpāti). And on top of that, like Nanaya and Gazbaba she was associated with sex. She certainly sounds more like a contemporary edgy oc of the Enoby Dimentia Raven Way variety than a bronze age goddess - and yet, she is completely genuine.

It is commonly argued Kanisurra and Gazbaba were regarded as Nanaya’s daughters, but there is actually no direct evidence for this. In the only text where their relation to Nanaya is clearly defined they are described as her hairdressers, rather than children.

While in some cases the love goddesses appear in love incantations in company of each other almost as if they were some sort of disastrous polycule, occasionally Nanaya is accompanied in them by an anonymous spouse. Together they occur in parallel with Inanna and Dumuzi and Ishara and Almanu, apparently a (accidental?) deification of a term referring to someone without family obligations.

There is only one Old Babylonian source which actually assigns a specific identity to Nanaya’s spouse, a hymn dedicated to king Abi-eshuh of Babylon. An otherwise largely unknown god Muati (I patched up his wiki article just for the sake of this blog post) plays this role here.

The text presents a curious case of reversal of gender roles: Muati is asked to intercede with Nanaya on behalf of petitioners. Usually this was the role of the wife - the best known case is Aya, the wife of Shamash, who is implored to do just that by Ninsun in the standard edition of the Epic of Gilgamesh. It’s also attested for goddesses such as Laz, Shala, Ninegal or Ninmug… and in the case of Inanna, for Ninshubur.

A Neo-Assyrian statue of Nabu on display in the Iraq Museum (wikimedia commons)

Marten Stol seems to treat Muati and Nabu as virtually the same deity, and on this basis states that Nanaya was already associated with the latter in the Old Babylonian period, but this seems to be a minority position. Other authors pretty consistently assume that Muati was a distinct deity at some point “absorbed” by Nabu.

The oldest example of pairing Nanaya with Nabu I am aware of is an inscription dated to the reign of Marduk-apla-iddina I, so roughly to the first half of the twelfth century BCE. The rise of this tradition in the first millennium BCE was less theological and more political. With Babylon once again emerging as a preeminent power, local theologies were supposed to be subordinated to the one followed in the dominant city. Which, at the time, was focused on Nabu, Marduk and Zarpanit. Worth noting that Nabu also had a spouse before, Tashmetum (“reconciliation”). In the long run she was more or less ousted by Nanaya from some locations, though she retained popularity in the north, in Assyria. She is not exactly the most thrilling deity to discuss. I will confess I do not find the developments tied to Nanaya and Nabu to be particularly interesting to cover, but in the long run they might have resulted in Nanaya acquiring probably the single most interesting “supporting cast member” she did not share with Inanna, so we’ll come back to this later.

Save for Bizilla, Nanaya generally was not provided with “equivalents” in god lists. I am only aware of one exception, and it’s a very recent discovery. Last year the first ever Akkadian-Amorite bilingual lists were published. This is obviously a breakthrough discovery, as before Amorite was largely known just from personal names despite being a vernacular language over much of the region in the bronze age, but only one line is ultimately of note here. In a section of one of the lists dealing with deities, Nanaya’s Amorite counterpart is said to be Pidray. This goddess is otherwise almost exclusively known from Ugarit. This of course fits very well with the new evidence: recent research generally stresses that Ugarit was quintessentially an Amorite city (the ruling house even claimed descent from mythical Ditanu, who is best known from the grandiose fictional genealogies of Shamshi-Adad I and the First Dynasty of Babylon).

Sadly, we do not know how the inhabitants of Ugarit viewed Nanaya. A trilingual version of the Weidner list, with the original version furnished with columns listing Ugaritic and Hurrian counterparts of each deity, was in circulation, but the available copies are too heavily damaged to restore it fully. And to make things worse, much of it seems to boil down to scribal wordplay and there is no guarantee all of the correspondences are motivated theologically. For instance, the minor Mesopotamian goddess Imzuanna is presented as the counterpart of Ugaritic weather god Baal because her name contains a sign used as a shortened logographic writing of the latter. An even funnier case is the awkward attempt at making it clear the Ugaritic sun deity Shapash, who was female, is not a lesbian… by making Aya male. Just astonishing, really.

The worship of Nanaya

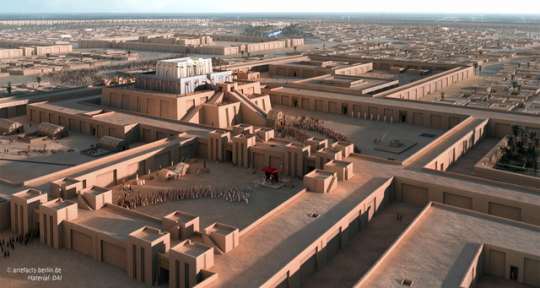

A speculative reconstruction of Ur III Uruk with the Eanna temple visible in the center (Artefacts — Scientific Illustration & Archaeological Reconstruction; reproduced here for educational purposes only, as permitted)

Rather fittingly, as a deity associated with Inanna, Nanaya was worshiped chiefly in Uruk. She is also reasonably well attested in the inscriptions of the short-lived local dynasty which regained independence near the end of the period of domination of Larsa over Lower Mesopotamia. A priest named after her, a certain Iddin-Nanaya, for a time served as the administrator of her temple, the Enmeurur, “house which gathers all the me,” me being a difficult to translate term, something like “divine powers”. The acquisition of new me is a common topic in Mesopotamian literature, and in compositions focused on Inanna in particular, so it should not be surprising to anyone that her peculiar double seemingly had similar interests.

In addition to Uruk, as well as Nippur and Ur, after the Ur III period Nanaya spread to multiple other cities, including Isin, Mari, Babylon and Kish. However, she is probably by far the best attested in Larsa, where she rose to the rank of one of the main deities, next to Utu, Inanna, Ishkur and Nergal. She had her own temple, the Eshahulla, “house of a happy heart”. In local tradition Inanna got to keep her role as an “universal” major goddess and her military prerogatives, but Nanaya overtook the role of a goddess of love almost fully. Inanna’s astral aspect was also locally downplayed, since Venus was instead represented in the local pantheon by closely associated, but firmly distinct, Ninsianna. This deity warrants some more discussion in the future just due to having a solid claim to being one of the first genderfluid literary figures in history, but due to space constraints this cannot be covered in detail here.

A later inscription from the same city differentiates between Nanaya and Inanna by giving them different epithets: Nanaya is the “queen of Uruk and Eanna” (effectively usurping Nanaya’s role) while Inanna is the “queen of Nippur” (that’s actually a well documented hypostasis of her, not to be confused with the unrelated “lady of Nippur”).

Uruk was temporarily abandoned in the late Old Babylonian period, but that did not end Nanaya’s career. Like Inanna, she came to be temporarily relocated to Kish. It has been suggested that a reference to her residence in “Kiššina” in a Hurro-Hittite literary text, the Tale of Appu, reflects her temporary stay there.

The next centuries of Nanaya are difficult to reconstruct due to scarce evidence, but it is clear she continued to be worshiped in Uruk. By the Neo-Babylonian period she was recognized as a member of an informal pentad of the main deities of the city, next to Inanna, Urkayitu, Usur-amassu and Beltu-sa-Resh. Two of them warrant no further discussion: Urkayitu was most likely a personification of the city, and Beltu-sa-Resh despite her position is still a mystery to researchers.

Usur-amassu, on the contrary, is herself a fascinating topic. First attestations of this deity, who was seemingly associated with law and justice (a pretty standard concern), come back to the Old Babylonian period. At this point, Usur-amassu was clearly male, which is reflected by the name. He appears in the god list An = Anum as a son of the weather deity couple par excellence, Adad (Ishkur) and Shala. However, by the early first millennium BCE Usur-amassu instead came to be regarded as female - without losing the connection to her parents. She did however gain a connection to Inanna, Nanaya and Kanisurra, which she lacked earlier. How come remains unknown. Most curiously her name was not modified to reflect her new gender, though she could be provided with a determinative indicating it. This recalls the case of Lagamal in the kingdom of Mari some 800 years earlier.

The end of the beginning: Nanaya under Achaemenids and Seleucids

Trilingual (Persian, Elamite and Akkadian) inscription of the first Achamenid ruler of Mesopotamia, Cyrus (wikimedia commons)

After the fall of the Neo-Babylonian Empire Mesopotamia ended up under Achaemenid control, which in turn was replaced by the Seleucids. Nanaya flourished through both of these periods. In particular, she attained considerable popularity among Arameans. While they almost definitely first encountered her in Uruk, she quickly came to be venerated by them in many distant locations, like Palmyra, Hatra and Dura Europos in Syria. She even appears in a single Achaemenid Aramaic papyrus discovered in Elephantine in Egypt. It indicates that she was worshiped there by a community which originated in Rash, an area east to the Tigris. As a curiosity it’s worth mentioning the same source is one of the only attestations of Pidray from outside Ugarit. I do not think this has anything to do with the recently discovered connection between her and Nanaya… but you may never know.

Under the Seleucids, Nanaya went through a particularly puzzling process of partial syncretism. Through interpretatio graeca she was identified with… Artemis. How did this work? The key to understanding this is the fact Seleucids actually had a somewhat limited interest in local deities. All that was necessary was to find relatively major members of the local pantheon who could roughly correspond to the tutelary deities of their dynasty: Zeus, Apollo and Artemis. Zeus found an obvious counterpart in Marduk (even though Marduk was hardly a weather god). Since Nabu was Marduk’s son, he got to be Apollo. And since Nanaya was the most major goddess connected to Nabu, she got to be Artemis. It really doesn’t go deeper than that.

For what it’s worth, despite the clear difference in character this newfound association did impact Nanaya in at least one way: she started to be depicted with attributes borrowed from Artemis, namely a bow and a crescent. Or perhaps these attributes were already associated with her, but came to the forefront because of the new role. The Artemis-like image of Nanaya as an archer is attested on coins, especially in Susa, yet another city where she attained considerable popularity.

Leaving Mesopotamia: Nanaya and the death of cuneiform

A Parthian statue of Nanaya with a crescent diadem (Louvre; reproduced here for educational purposes only. Identification follows Andrea Sinclair's proposal)

The Seleucid dynasty was eventually replaced by the Parthians. This period is often considered a symbolic end of ancient Mesopotamian religion in the strict sense. Traditional religious institutions were already slowly collapsing in Achaemenid and Seleucid times as the new dynasties had limited interest in royal patronage. Additionally, cuneiform fell out of use, and by the end of the first half of the first millennium CE the art of reading and writing it was entirely lost. This process did not happen equally quickly everywhere, obviously, and some deities fared better than others in the transitional period before the rise of Christianity and Islam as the dominant religions across the region. Nanaya was definitely one of them, at least for a time.

In Parthian art Nanaya might have developed a distinct iconography: it has been argued she was portrayed as a nude figure wearing only some jewelry (including what appears to be a navel piercing and a diadem with a crescent. The best known example is probably this standing figure, one of my all time favorite works of Mesopotamian art:

Parthian Nanaya (wikimedia commons; identification courtesy of the Louvre website and J. G. Westenholz)

For years Wikipedia had this statue mislabeled as “Astarte” which makes little sense considering it comes from a necropolis near Babylon. There was also a viral horny tweet which labeled it as “Asherah” a few months ago (I won’t link it but I will point out in addition to getting the name wrong op also severely underestimated the size). This is obviously even worse nonsense both on spatial and temporal grounds. Even if the biblical Asherah was ever an actual deity like Ugaritic Athirat and Mesopotamian Ashratum, it is highly dubious she would still be worshiped by the time this statue was made. It’s not even certain she ever was a deity, though. Cognate of a theonym is not automatically a theonym itself, and the Ugaritic texts and the Bible, even if they share some topoi, are separated by centuries and a considerable distance. This is not an Asherah post though, so if this is a topic which interests you I recommend downloading Steve A. Wiggins’ excellent monograph A Reassessment of Asherah: With Further Considerations of the Goddess.

The last evidence for the worship of Nanaya in Mesopotamia is a Mandaean spell from Nippur, dated to the fifth or sixth century CE. However, at this point Nanaya must have been a very faint memory around these parts, since the figure designated by this name is evidently male in this formula. That was not the end of her career, though. The system of beliefs she originated and thrived in was on its way out, but there were new frontiers to explore.

A small disgression is in order here: be INCREDIBLY wary of claims about the survival of Mesopotamian tradition in Mesopotamia itself past the early middle ages. Most if not all of these come from the writing of Simo Parpola, who is a 19th century style hyperdiffusionist driven by personal religious beliefs based on gnostic christianity, which he believes was based on Neo-Assyrian state religion, which he misinterprets as monotheism, or rather proto-christianity specifically (I wish I was making this up). I personally do not think a person like that should be tolerated in serious academia, but for some incomprehensible reason that isn’t the case.

New frontiers: Nanaya in Bactria

The key to Nanaya’s extraordinarily long survival wasn’t the dedication to her in Mesopotamia, surprisingly. It was instead her introduction to Bactria, a historical area in Central Asia roughly corresponding to parts of modern Afghanistan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. The early history of this area is still poorly known, though it is known that it was one of the “cradles of civilization” not unlike Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley or Mesoamerica. The so-called “Oxus civilization” or “Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex” flourished around 2500-1950 BCE (so roughly contemporarily with the Akkadian and Ur III empires in Mesopotamia). It left behind no written records, but their art and architecture are highly distinctive and reflect great social complexity.

I sadly can’t spent much time discussing them here though, as they are completely irrelevant to the history of Nanaya (there is a theory that she was already introduced to the east when BMAC was extant but it is incredibly implausible), so I will limit myself to showing you my favorite related work of art, the “Bactrian princess”:

Photo courtesy of Louvre Abu Dhabi, reproduced here for educational purposes only.

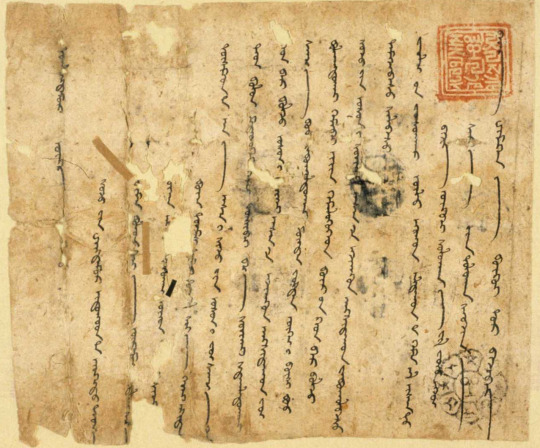

By late antiquity, which is the period we are concerned with here, BMAC was long gone, and most of the inhabitants of Bactria spoke Bactrian, an extinct Iranian language. How exactly they were related to their BMAC forerunners is uncertain. Their religious beliefs can be compared to Zoroastrianism, or rather with its less formalized forerunners followed by most speakers of Iranian languages before the rise of Zoroaster. However, there were many local peculiarities. For example, the main deity was the personified river Oxus, not Ahura Mazda. Whether this was a relic of BMAC religion is impossible to tell.We do not know exactly when the eastward transfer of Nanaya to Bactria happened. The first clear evidence for her presence in central Asia comes from the late first century BCE, from the coins of local rulers, Sapadbizes and Agesiles. It is possible that her depictions on coinage of Mesopotamian and Persian rulers facilitated her spread. Of course, it’s also important to remember that the Aramaic script and language spread far to the east in the Achaemenid period already, and that many of the now extinct Central Asian scripts were derived from it (Bactrian was written with the Greek script, though). Doubtlessly many now lost Aramaic texts were transferred to the east.

There’s an emerging view that for unclear reasons, under the Achaemenids Mesopotamian culture as a whole had unparalleled impact on Bactria. The key piece of evidence are Bactrian temples, which often resemble Mesopotamian ones. Therefore, perhaps we should be wondering not why Nanaya spread from Mesopotamia to Central Asia, but rather why there were no other deities who did, for the most part. That is sadly a question I cannot answer. Something about Nanaya simply made her uniquely appealing to many groups at once.

While much about the early history of Nanaya in Central Asia is a mystery, it is evident that with time she ceased to be viewed as a foreign deity. For the inhabitants of Bactria she wasn’t any less “authentically Iranian” than the personified Oxus or their versions of the conventional yazatas like Sraosha. Frequently arguments are made that Nanaya’s widespread adoption and popularity could only be the result of identification between her and another deity.Anahita in particular is commonly held to be a candidate. However, as stressed by recent studies there’s actually no evidence for this.

What is true is that Anahita is notably missing from the eastern Iranian sources, despite being prominent in the west from the reign of the Achaemenid emperor Artaxerxes II onward. However, it is clear that not all yazatas were equally popular in each area - pantheons will inevitably be localized in each culture. Furthermore, Anahita’s character has very little in common with Nanaya save for gender. Whether we are discussing her early not quite Zoroastrian form the Achaemenid public was familiar with or the contemporary yazata still relevant in modern Zoroastrianism, the connection to water is the most important feature of her. Nanaya didn’t have such a role in any culture.

Recently some authors suggested a much more obvious explanation for Anahita’s absence from the eastern Iranian pantheon(s). As I said, eastern Iranian communities venerated the river Oxus as a deity (or as a yazata, if you will). He was the water god par excellence, and in Bactria also the king of the gods. It is therefore quite possible that Anahita, despite royal backing from the west, simply couldn’t compete with him. Their roles overlapped more than the roles of Anahita and Nanaya. I am repeating myself but the notion of interchangeability of goddesses really needs to be distrusted almost automatically, no matter how entrenched it wouldn’t be. While we’re at it, the notion of alleged interchangeability between Anahita and Ishtar is also highly dubious, but that’s a topic for another time.

Nana (Nanaya) on a coin of Kanishka (wikimedia commons)

Nanaya experienced a period of almost unparalleled prosperity with the rise of the Kushan dynasty in Bactria. The Kushans were one of the groups which following Chinese sources are referred to as Yuezhi. They probably did not speak any Iranian language originally, and their origin is a matter of debate. However, they came to rule over a kingdom which consisted largely of areas inhabited by speakers of various Iranian languages, chiefly Bactrian. Their pantheon, documented in royal inscriptions and on coinage, was an eerie combination of mainstays of Iranian beliefs like Sraosha and Mithra and some unique figures, like Oesho, who was seemingly the reflection of Hindu Shiva. Obviously, Nanaya was there too, typically under the shortened name Nana.

The most famous Kushan ruler, emperor Kanishka, in his inscription from Rabatak states that kingship was bestowed upon him by “Nana and all the gods”. However, we do not know if the rank assigned to her indicates she was the head of the dynastic pantheon, the local pantheon in the surrounding area, or if she was just the favorite deity of Kanishka. Same goes for the rank of numerous other deities mentioned in the rest of the inscription. Her apparent popularity during Kanishka’s reign and beyond indicates her role should not be downplayed, though.

The coins of Kanishka and other Bactrian art indicate that a new image of Nanaya developed in Central Asia. The Artemis-like portrayals typical for Hellenistic times continue to appear, but she also started to be depicted on the back of a lion. There is only one possible example of such an image from the west, a fragmentary relief from Susa, and it’s roughly contemporary with the depictions from Bactria. While it is not impossible Nanaya originally adopted the lion association from one of her Mesopotamian peers, it is not certain how exactly this specific type of depictions originally developed, and there is a case to be made that it owed more to the Hellenistic diffusion of iconography of deities such as Cybele and Dionysus, who were often depicted riding on the back of large felines.

The lunar symbols are well attested in the Kushan art of Nanaya too. Most commonly, she’s depicted wearing a diadem with a crescent. However, in a single case the symbol is placed behind her back. This is an iconographic type which was mostly associated with Selene at first, but in the east it was adopted for Mah, the Iranian personification of the moon. I’d hazard a guess that’s where Nanaya borrowed it from - more on that later.

The worship of Nanaya survived the fall of the Kushan dynasty, and might have continued in Bactria as late as in the eighth century. However, the evidence is relatively scarce, especially compared with yet another area where she was introduced in the meanwhile.

Nanaya in Sogdia: new home and new friends

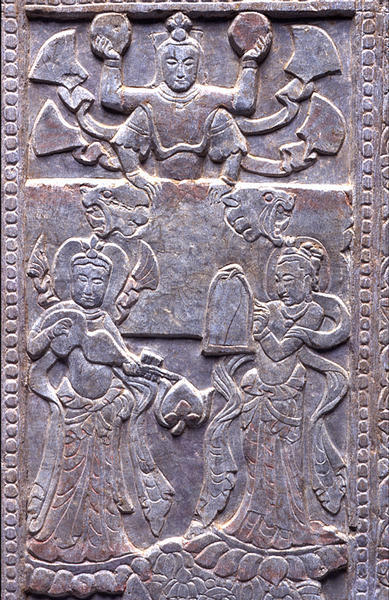

A Sogdian depiction of Nanaya from Bunjikat (wikimedia commons)

Presumably from Bactria, Nanaya was eventually introduced to Sogdia, its northern neighbor. I think it’s safe to say this area effectively became her new home for the rest of her history.

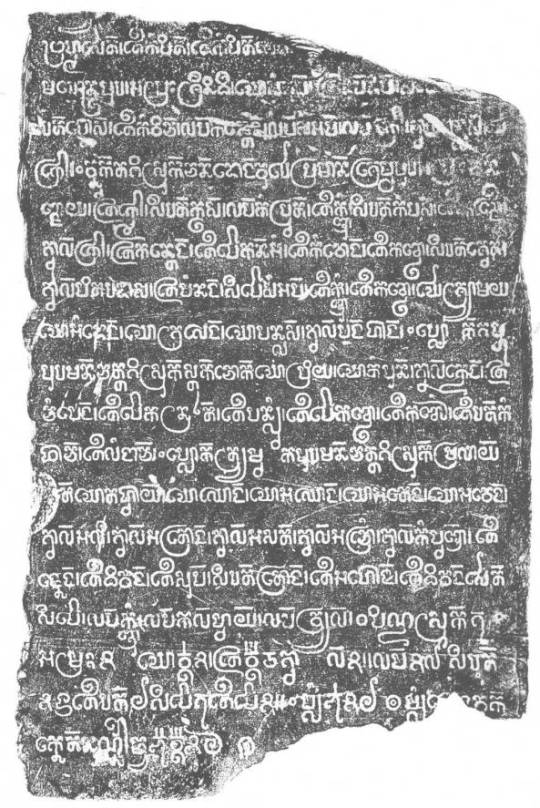

Like Bactrians, the Sogdians also spoke an eastern Iranian language, Sogdian. It has a direct modern descendant, Yaghnobi, spoken by a small minority in Tajikistan. The religions Sogdians adhered to is often described as a form of Zoroastrianism, especially in older sources, but it would appear that Ahura Mazda was not exactly the most popular deity. Their pantheon was seemingly actually headed by Nanaya. Or, at the very least, the version of it typical for Samarkand and Panijkant, since there’s a solid case to be made for local variety in the individual city-states which made up Sogdia. It seems that much like Mesopotamians and Greeks centuries before them, Sogdians associated specific deities with specific cities, and not every settlement necessarily venerated each deity equally (or at all). Nanaya's remarkable popularity is reflected by the fact the name Nanaivandak, "servant of Nanaya", is one of the most common Sogdian names in general.

It is agreed that among the Sogdians Panjikant was regarded as Nanaya’s cult center. She was referred to as “lady” of this city. At one point, her temple located there was responsible for minting the local currency. By the eighth century, coins minted there were adorned with dedications to her - something unparalleled in Sogdian culture, as the rest of coinage was firmly secular. This might have been an attempt at reasserting Sogdian religious identity in the wake of the arrival of Islam in Central Asia.

Sogdians adopted the Kushan iconography of Nanaya, though only the lion-mounted version. The connection between her and this animal was incredibly strong in Sogdian art, with no other deity being portrayed on a similar mount. There were also innovations - Nanaya came to be frequently portrayed with four arms. This reflects the spread of Buddhism through central Asia, which brought new artistic conventions from India. While the crescent symbol can still be found on her headwear, she was also portrayed holding representations of the moon and the sun in two of her hands.

Sometimes the solar disc and lunar orb are decorated with faces, which has been argued to be evidence that Nanaya effectively took over the domains of Mah and Mithra, who would be the expected divine identities of these two astral bodies. She might have been understood as controlling the passage of night and day. It has also been pointed out that this new iconographic type is the natural end point of the evolution of her astral role.

Curiously, while no such a function is attested for Nanaya in Bactria, in Sogdia she could be sometimes regarded as a warlike deity. This is presumably reflected in a painting showing her and an unidentified charioteer fighting demons.

The "Sogdian Deities" painting from Dunhuang, a possible depiction of Nanaya and her presumed spouse Tish (wikimedia commons)

Probably the most fascinating development regarding Nanaya in Sogdia was the development of an apparent connection between her and Tish. This deity was the Sogdian counterpart of one of the best known Zoroastrian yazatas, Tishtrya, the personification of Sirius. As described in the Tištar Yašt, the latter is a rainmaking figure and a warlike protector who keeps various nefarious forces, such as Apaosha, Duzyariya and the malign “worm stars” (comets), at bay. Presumably his Sogdian counterpart had a similar role.

While this is not absolutely certain, it is generally agreed that Nanaya and Tish were regarded as a couple in central Asia (there’s a minority position she was instead linked with Oesho, though). Most likely the fact that in Achaemenid Persia Tishtrya was linked with Nabu (and by extension with scribal arts) has something to do with this. There is a twist to this, though.

While both Nabu and the Avestan Tishtrya are consistently male, in Bactria and Sogdia the corresponding deity’s gender actually shows a degree of ambiguity. On a unique coin of Kanishka, Tish is already portrayed as a feminine figure distinctly similar to Greek Artemis - an iconographic type which normally would be recycled for Nanaya. There’s also a possibility that a feminine, or at least crossdressing, version of Tish is portrayed alongside Nanaya on a painting from Dunhuang conventionally referred to as “Sogdian Daēnās” or “Sogdian Deities”, but this remains uncertain. If this identification is correct, it indicates outright interchange of attributes between them and Nanaya was possible.

The final frontier: Nanaya and the Sogdian diaspora in China