#forest products in India

Text

What Is The Size Of The Forest Products Industry In India?

The forest products industry in India is diverse and plays a crucial role in the country's economy. Numerous manufacturers are producing a wide range of products derived from forest resources.

The forest products industry involves the production of goods and services derived from forest resources. And this crucial sector includes both timber and non-timber products. This industry plays an important role in the growth and development of the economy as it has a significant impact on rural communities and the environment.

Classification Of Forest Produce

1. Timber products

This includes sawn timber, plywood, veneers, and other wood-based products derived from forests. These products have wide applications in construction, furniture, and interior design manufacturing

2. Paper products

Paper is needed for the publishing industry and includes newsprint, printing paper, tissue paper, packaging, and other products made from wood pulp. These products have wide applications in both residential and commercial sectors.

3. Non-timber forest products (NTFPs)

It includes a wide range of products derived from forest resources other than timber. Examples include rubber, resin, honey, nuts, mushrooms, and medicinal plants. There could be more products available depending on location and environment.

Bioenergy: Forests are a crucial source of bioenergy, including wood pellets, chips, and other biomass products used to generate electricity, heat buildings, and fuel vehicles.

India has a diverse range of forests that are home to a variety of tree species, many of which are used for different forest products. Some of the important forest products in India include the following:

Timber: India has several timber species that are used for furniture, construction, and other purposes. Some popular timber species include teak, rosewood, sal, deodar, sandalwood, and bamboo. The country has vast reserves of forests that provide quality timber.

Medicinal plants: India has a rich tradition of using medicinal plants for healthcare. Many of these plants are found in the forests and are used to produce medicines, herbal teas, and other health products. In addition, they are used to flavor cosmetics and health foods as nutritional supplements.

Non-timber forest products (NTFPs): NTFPs are products that are derived from forest resources other than timber. Some examples of NTFPs in India include honey, beeswax, bamboo shoots, mushrooms, and various spices. These products are in great demand in both domestic and global markets.

Paper: India has a large paper industry that relies on wood pulp for paper production. The country has several paper mills that use different types of wood for paper production. It has a significant contribution to the country's economy.

Rubber: India is one of the major producers of natural rubber, which is extracted from rubber trees found in forest areas. Rubber is used for various purposes in different industries.

Fruits and nuts: Many forest areas in India are home to mixed fruit and nut trees such as mango, jackfruit, cashew, and walnut. These products have generated huge demand in both domestic and global markets.

Lac: Lac is a resinous substance secreted by an insect and used in the production of shellac, which is used in making varnish, wax, and other products. India is one of the major producers of lac in the world. Also, the country has initiated a special program to promote lac farming.

Government Initiative

The government formed Shellac Export Promotion Council (SEPC) in 1956 to promote the export of shellac and shellac-based products. Shellac is a resinous substance that is secreted by the female lac bug and is used in the production of various products, including varnishes, food glazes, and pharmaceuticals.

The SEPC is responsible for promoting the export of shellac and shellac-based products and providing support to shellac manufacturers and exporters. The council works closely with government agencies, industry associations, and other stakeholders to promote the use of shellac in various industries and to increase its export potential.

The Shellac Export Promotion Council works to create awareness about Indian shellac and forest products in the international market by organizing trade fairs, buyer-seller meets, and exhibitions. It also provides various kinds of assistance to exporters, such as information on market trends, opportunities, and regulatory requirements.

The SEPC is crucial in promoting and supporting the export of shellac and other forest products from India. Its various activities and initiatives help to increase the demand for Indian products and enhance the competitiveness of Indian exporters in the international market.

India has a thriving forest sector, with numerous manufacturers producing various products derived from forest resources. Some of the big forest products manufacturers in India include:

Greenply Industries: Greenply is one of the largest producers of plywood and other wood-based products in India. The company operates several manufacturing facilities across the country and offers a range of products, including plywood, veneers, and laminates.

Century Plyboards: Century Plyboards is another major player in the Indian Plywood industry, producing a wide range of plywood, veneers, and laminates. The company also operates a manufacturing facility that produces particleboard and MDF.

Dabur India: Dabur is a well-known Indian company that produces a range of ayurvedic and herbal products, including those derived from forest resources. The company is a major producer of honey, which is sourced from forest areas.

TTK Prestige: TTK Prestige is a manufacturer of kitchen appliances, including cookware and other products made from non-timber forest products like bamboo. The company sources bamboo from sustainable plantations and supports local communities through its operations.

Godrej and Boyce: Godrej and Boyce is a diversified company with operations in various sectors, including forest goods. The company produces a wide range of furniture, including those made from timber and other materials.

Cello Industries: Cello Industries is a manufacturer of plastic and composite products, including those made from bamboo composite. One of the most important forest-based industries, the company sources bamboo from sustainable plantations and produces a range of products, including furniture, flooring, and other items.

#forest-based industries#forest#forest products#forest products manufacturers#forest products industry#forest products in India#Indian forest

0 notes

Text

gothic culture flew so dark academia could walk, in this essay i will.. ☕📜

#studyblr#student#aesthetic#100dop#100 days of productivity#studyblr india#poc studyblr#indian studyblr#tbr#essays#goth aesthetic#gothic#gothic tales#goth#trees#trees and forests#tell me why my walks take me to such hauntingly beautiful places

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The World's Forests Are Doing Much Better Than We Think

You might be surprised to discover... that many of the world’s woodlands are in a surprisingly good condition. The destruction of tropical forests gets so much (justified) attention that we’re at risk of missing how much progress we’re making in cooler climates.

That’s a mistake. The slow recovery of temperate and polar forests won’t be enough to offset global warming, without radical reductions in carbon emissions. Even so, it’s evidence that we’re capable of reversing the damage from the oldest form of human-induced climate change — and can do the same again.

Take England. Forest coverage now is greater than at any time since the Black Death nearly 700 years ago, with some 1.33 million hectares of the country covered in woodlands. The UK as a whole has nearly three times as much forest as it did at the start of the 20th century.

That’s not by a long way the most impressive performance. China’s forests have increased by about 607,000 square kilometers since 1992, a region the size of Ukraine. The European Union has added an area equivalent to Cambodia to its woodlands, while the US and India have together planted forests that would cover Bangladesh in an unbroken canopy of leaves.

Logging in the tropics means that the world as a whole is still losing trees. Brazil alone removed enough woodland since 1992 to counteract all the growth in China, the EU and US put together. Even so, the planet’s forests as a whole may no longer be contributing to the warming of the planet. On net, they probably sucked about 200 million metric tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere each year between 2011 and 2020, according to a 2021 study. The CO2 taken up by trees narrowly exceeded the amount released by deforestation. That’s a drop in the ocean next to the 53.8 billion tons of greenhouse gases emitted in 2022 — but it’s a sign that not every climate indicator is pointing toward doom...

More than a quarter of Japan is covered with planted forests that in many cases are so old they’re barely recognized as such. Forest cover reached its lowest extent during World War II, when trees were felled by the million to provide fuel for a resource-poor nation’s war machine. Akita prefecture in the north of Honshu island was so denuded in the early 19th century that it needed to import firewood. These days, its lush woodlands are a major draw for tourists.

It’s a similar picture in Scandinavia and Central Europe, where the spread of forests onto unproductive agricultural land, combined with the decline of wood-based industries and better management of remaining stands, has resulted in extensive regrowth since the mid-20th century. Forests cover about 15% of Denmark, compared to 2% to 3% at the start of the 19th century.

Even tropical deforestation has slowed drastically since the 1990s, possibly because the rise of plantation timber is cutting the need to clear primary forests. Still, political incentives to turn a blind eye to logging, combined with historically high prices for products grown and mined on cleared tropical woodlands such as soybeans, palm oil and nickel, mean that recent gains are fragile.

There’s no cause for complacency in any of this. The carbon benefits from forests aren’t sufficient to offset more than a sliver of our greenhouse pollution. The idea that they’ll be sufficient to cancel out gross emissions and get the world to net zero by the middle of this century depends on extraordinarily optimistic assumptions on both sides of the equation.

Still, we should celebrate our success in slowing a pattern of human deforestation that’s been going on for nearly 100,000 years. Nothing about the damage we do to our planet is inevitable. With effort, it may even be reversible.

-via Bloomburg, January 28, 2024

#deforestation#forest#woodland#tropical rainforest#trees#trees and forests#united states#china#india#denmark#eu#european union#uk#england#climate change#sustainability#logging#environment#ecology#conservation#ecosystem#greenhouse gasses#carbon emissions#climate crisis#climate action#good news#hope

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

What it meant to "do geology" in Hutton's time was to apply lessons of textual hermeneutics usually reserved for scripture [...] to the landscape. Geology was itself textual. Rocks were marks made by invisible processes that could be deciphered. Doing geology was a kind of reading, then, which existed in a dialectical relationship with writing. In The Theory of the Earth from 1788, Hutton wrote a new history of the earth as a [...] system [...]. Only a few kilometers away from Hutton’s unconformity [the geological site at Isle of Arran in Scotland that inspired his writing], [...] stands the remains of the Shell bitumen refinery [closed since 1986] as it sinks into the Atlantic Ocean. [...] As Hutton thought, being in a place is a hermeneutic practice. [...] [T]he Shell refinery at Ardrossan is a ruin of that machine, one whose great material derangements have defined the world since Hutton. [...]

The Shell Transport and Trading Company [now the well-known global oil company] was created in the Netherlands East Indies in 1897. The company’s first oil wells and refineries were in east Borneo [...]. The oil was taken by puncturing wells into subterranean deposits of a Bornean or Sumatran landscape, and then transported into an ever-expanding global network of oil depots at ports [...] at Singapore, then Chennai, and through the Suez Canal and into the Mediterranean. [...] The oil in these networks were Bornean and Sumatran landscapes on the move. Combustion engines burnt those landscapes. Machinery was lubricated by them. They illuminated the night as candlelight. [...] The Dutch East Indies was the new land of untapped promise in that multi-polar world of capitalist competition. British and Dutch colonial prospectors scoured the forests, rivers, and coasts of Borneo [...]. Marcus Samuel, the British founder of the Shell Transport and Trading Company, as his biographer [...] put it, was “mesmerized by oil, and by the vision of commanding oil all along the line from production to distribution, from the bowels of the earth to the laps of the Orient.” [...]

---

Shell emerged from a Victorian era fascination with shells.

In the 1830s, Marcus Samuel Sr. created a seashell import business in Houndsditch, London. The shells were used for decorating the covers of curio boxes. Sometimes, the boxes also contained miniature sculptures, also made from shells, of food and foliage, hybridizing oceanic and terrestrial life forms. Wealthy shell enthusiasts would sometimes apply shells to grottos attached to their houses. As British merchant vessels expanded into east Asia after the dissolution of the East India Company’s monopoly on trade in 1833, and the establishment of ports at Singapore and Hong Kong in 1824 and 1842, the import of exotic shells expanded.

Seashells from east Asia represented the oceanic expanse of British imperialism and a way to bring distant places near, not only the horizontal networks of the empire but also its oceanic depths.

---

The fashion for shells was also about telling new histories. The presence of shells, the pecten, or scallop, was a familiar bivalve icon in cultures on the northern edge of the Mediterranean. Aphrodite, for example, was said to have emerged from a scallop shell. Minerva was associated with scallops. Niches in public buildings and fountains in the Roman empire often contained scallop motifs. St. James, the patron saint of Spain, was represented by a scallop shell [...]. The pecten motif circulated throughout medieval European coats of arms, even in Britain. In 1898, when the Gallery of Palaeontology, Comparative Anatomy, and Anthropology was opened in Paris’s Museum of Natural History - only two years after the first test well was drilled in Borneo at the Black Spot - the building’s architect, Ferdinand Dutert, ornamented the entrance with pecten shell reliefs. In effect, Dutert designed the building so that one entered through scallop shells and into the galleries where George Cuvier’s vision of the evolution of life forms was displayed [...]. But it was also a symbol for the transition between an aquatic form of life and terrestrial animals. Perhaps it is apposite that the scallop is structured by a hinge which allows its two valves to rotate. [...] Pectens also thrive in the between space of shallow coastal waters that connects land with the depths of the ocean. [...] They flourish in architectural imagery, in the mind, and as the logo of one of the largest ever fossil fuel companies. [...]

---

In the 1890s, Marcus Samuel Jr. transitioned from his father’s business selling imported seashells to petroleum.

When he adopted the name Shell Transport and Trading Company in 1897, Samuel would likely have known that the natural history of bivalves was entwined with the natural history of fossil fuels. Bivalves underwent an impressive period of diversification in the Carboniferous period, a period that was first named by William Conybeare and William Phillips in 1822 to identify coal bearing strata. In other words, the same period in earth’s history that produced the Black Spot that Samuel’s engineers were seeking to extract from Dayak land was also the period that produced the pecten shells that he named his company after. Even the black fossilized leaves that miners regularly encountered in coal seams sometimes contained fossilized bivalve shells.

The Shell logo was a materialized cosmology, or [...] a cosmogram.

Cosmograms are objects that attempt to represent the order of the cosmos; they are snapshots of what is. The pecten’s effectiveness as a cosmogram was its pivot, to hinge, between spaces and times: it brought the deep history of the earth into the present; the Black Spot with Mediterranean imaginaries of the bivalve; the subterranean space of liquid oil with the surface. The history of the earth was made legible as an energetic, even a pyrotechnical force. The pecten represented fire, illumination, and certainly, power. [...] If coal required tunnelling, smashing, and breaking the ground, petroleum was piped liquid that streamed through a drilled hole. [...] In 1899, Samuel presented a paper to the Society of Arts in which he outlined his vision of “liquid fuel.” [...] Ardrossan is a ruin of that fantasy of a free flowing fossil fuel world. [...] At Ardrossan, that liquid cosmology is disintegrating.

---

All text above by: Adam Bobbette. "Shells and Shell". e-flux Architecture (Accumulation series). November 2023. At: e-flux dot com slash architecture/accumulation/553455/shells-and-shell/ [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticisms purposes.]

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you're from Argentina, you've probably heard about the Iberá wetlands, and you know the tourist pitch: a vast expanse of natural wonders in the middle of Corrientes, full of beautiful lapachos, cute carpinchos and yacarés, and now home to the fastest-growing wild yaguareté population, all with the unique Guaraní influenced culture of rural Corrientes.

Now, things aren't as shiny as they look, since the creation and management of the new national park is still a point of contention in many ways, but you will be suprised that this kind of thinking about the Iberá is very, very recent. Most people considered it an obstacle to progress, a big bunch of swamp in the middle of what could be a very productive ranching province. In a geography book from the 1910s (unfortunately I lost the screencap) it says something like "the biggest obstacle for the development of the province is this swamp, and it should be drained"

This took me to the other side of the world, to the Netherlands. They're known for land reclamation, from literally building their country from the sea. Especially when we're facing rising sea levels because of climate change, the Dutch seem like miracle workers, a look into our future. You will find no shortage of praise about how with some windmills and dams, the Dutch took land "from the sea", and turned it into quaint little polders, making a tiny country in Europe a food exporter and don't they look so nice? But when you look about it, you can barely find anything about what came before those polders. You have to dig and dig to find any mentions of not "sea", but of complex tidal marshes and wetlands, things I've learned are ecologically diverse and protected in many places, but you won't find people talking about that at all when talking about the Netherlands. It's all just polders now. What came before was useless swamp, or a sea to be triumphantly conquered. It's like they were erased from history

The use of that language reminded me of the failed vision of draining Iberá... and the triumphing vision in the Netherlands, and many other places. Maybe those wonderful places, those unique wetlands, would have been a footnote, you wouldn't find anything unless you were a bored ecologist who looked, and not even then. Now, far it be from me to accuse the medieval Dutch, who wanted to have more space to farm, of ecocide. And don't think this is going to be a rant against European ecological imperialism either, as the most anthropized places you can find are actually in China and India. But it does get me thinking.

I work with the concept of landscape, and landscape managing. (Not landscaping, those guys get better paid than me) The concept of landscape is somewhat similar to the concept of ecosystem you know from basic biology, but besides biotic and abiotic factors, you also have to involve cultural factors, that is, humans. There is not a single area of "pristine" untouched nature in the world, that is a myth. Humans have managed these landscapes for as long as they have lived in them. The Amazon, what many people think about when they think about "unspoilt" nature, has a high proportion of domesticated plants growing on it, which were and are still used by the people who live on it, and there once were great civilizations thriving on it. Forests and gardens leave their mark, so much that we can use them to find abandoned settlements. From hunter-gatherers tending and preserving the species vital to their survival in the tundra to engineers in Hong-Kong creating new islands for airports, every human culture has managed their natural resources, creating a landscape.

And this means these landscapes we enjoy are not natural creations. They are affected by natural enviroments; biomes do exist, species have a natural distribution. But they are created and managed by humans. Humans who decide what is valuable to them and what is not. The Dutch, seemingly, found the tidal marshes useless, and they created a new landscape, which changed the history of their nation forever. We here in modern Argentina changed our perception of Iberá, decided to take another approach, and now we made it a cherished part of our heritage, which will also speak about us in the future.

Ultimately, what is a useless swamp to be drained or a beautiful expanse of nature to be cherished depends in our culture, in us humans. We are the ones who manage and change ecosystems based in our economics, our culture, our society. This will become increasingly important, as climate change and ecological degradation becomes harsher and undeniable. We will have to decide what nature is worth to us. Think about what is it worth to you.

#I REALLY had to restrain myself not to make a football joke about the netherlands#cosas mias#ecology#biology#culture#cultural landscapes

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

Genderqueer Folktales (part 2)

I’ve gathered some new gender nonconforming folktales since making part 1, so it’s time for a new post! Again, please keep in mind these are all translations and products of their time. I will still attempt to put some modern-day labels on them to make them easier to navigate:

The Story of the Maiden-Knight

Indian legend, published in 1916, based on the Mahabharata.

[Cw: being outed, threat of violence, awkward use of pronouns.]

A king prays for a son to go to battle his enemy, but the god Shiva reveals to him that he “should have a son who should first be a daughter”. Accordingly the child born to them – Shikhandi – is raised as a boy and married to a princess. When he finds out the situation the bride’s father is furious however, and wants to go to war over it. Shikhandi goes into the forest, in the hope that without him there will be no war. There he meets a kind Yakshas (nature spirit) who is willing to lend Shikhandi his manhood until he has saved his father from this threat. But when the king of the Yakshas finds out about this he decrees that the Yakshas will not get his manhood back until Shikhandi’s death.

The Stirrup Moor

Albanian folktale, published in 1895.

[Cw: violence, king attempts to steal son’s wives, some uncomfortable descriptions of a black person.]

A prince, through his many adventures, wins the love of three wives: one human lady, one jinn princess, and one Earthly Beauty (a type of fae-like spirit from the underworld). The latter of the three regularly changes between her supernatural female shape and her chosen human form, that of a black man. In this male shape he is a formidable warrior and helps protect both the prince and the other wives. All four eventually live happily ever after.

The Boy-Girl and the Girl-Boy

A Gond folktale from Central India, published in 1944.

[Cw: attempt at being outed, awkward use of gendered terms and pronouns, some doubt as to whether the AFAB protagonist is completely happy with the physical change.]

An AFAB child is adopted by a Raja, who accepts him as his son. Near the palace an old woman raises one of her many AMAB children as a girl and arranges a marriage for her. The young couple is very startled at finding out they have “the same parts” but there are not other repercussions. Later the young wife doesn’t dare to go bathing with the other women and meets the Raja’s adopted son, who has run away and changed himself into a bird. The bird offers to “exchange parts” and both protagonists end the story with a body matching their presented gender.

The Girl Who Became a Boy

Albanian folktale, published in 1879.

[Cw: preoccupation with sexual ability, attempts to kill protagonist.]

AFAB protagonist answers the king’s call for warriors, dressed as a man. After several great deeds the young man wins a princess’s hand in marriage in another kingdom. He is liked at the court, but they feel obliged to get rid of him because he seems unable to consummate his marriage. He survives every dangerous task, however, and finally is sent to confront a snake infested church. The snakes curse him to become a boy, after which he returns to the court and all ends well.

With an affectionate mention for the 13th century French poem Yde and Olive, which was brought to my attention by @pomme-poire-peche. You can read about this brave princess-turned-knight married to a loyal princess here.

#trans representation#gender nonconforming folklore#genderqueer folktales#trans fairy tales#sources#laura retells

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why should I strive to accurately reflect your argument when you've refused to do the same with climate change? Ignoring all evidence of humans being capable of affecting their environment and dismissively referring to it as "controlling the weather" which is not close to anyone's argument. The problem isn't me not repeating your argument the problem is you don't like people treating you the same way as you treat others.

Except you guys think that you can literally control the weather if we just tax enough billionaires, regulate enough energy industries, and give up enough freedoms. If the goal is to reduce global carbon emissions, not a single proposed plan to "fight climate change" would do that because they all ignore China and India, which are by far the largest producers of artificial carbon in the world. Even if the west turned off every coal plant and banned carbon production tomorrow, China and India would still be putting out way more carbon than we reduced, to the point where reducing our "carbon footprint" is meaningless. What these plans do accomplish, though, is restricting our freedoms and granting government greater control over the lives of individuals and what's left of the free market. None of the people pushing this climate narrative seem very interested in actually fighting the supposed source of "climate change", so why should I take them seriously?

Humans do affect the environment. I never said otherwise. That's your strawman. My argument is that, if the climate is changing, then human activity is not the main cause. And that's a pretty big if, since your side loves to claim that any weather is evidence of "climate change". One hurricane goes farther north than most hurricanes do? Climate change! Normal amount of hurricanes during hurricane season? Climate change! Indian summer? Climate change! Blizzard in winter? Climate change! Forest fires in a dry, brush covered forest that was started by a human? Climate change! Christ, you people even blame civil wars and riots on climate change. Combine all that with the fact that literally every single climate apocalypse that has ever been predicted, many using the same climate models "scientists" rely on today for their predictions, has never come true, and yeah, I don't believe "the experts" or their manipulated data when they say "No, this time we're totally right you guys. Climate apocalypse is right around the corner!" Climate cultists, because you people do act like a cult, are doing their own supposed cause no favors by acting like hysterical children who keep saying the sky is gonna fall any day now.

I'll make the same deal with you that I've made with other climate weirdos. You live your life like the world is going to end any year now, and I'll live my life like it's not. In 50 years, we can meet up and see which one of us was right and which one of us enjoyed their life more. Maybe on one of the coasts that won't be even remotely close to being underwater.

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Indian state has already begun to evict indigenous communities from their homes. In late 2020, tribal communities received notice that labeled their homes as illegally occupying forest land. Their homes were demolished. This bears an eerie resemblance to Israel's targeting of Bedouin communities of Naqab, where Israel gave the lands of these communities to Jewish settlers and the military. The logic of Bedouin dispossession was premised on the fact that as nomads, they had no right to the land.

In Kashmir, these communities were living on lands that the Indian state wanted to use for the development of tourist infrastructure. Part of the plan is to transfer agricultural land to Indian state and private corporations. Kashmir has already lost 78,700 hectares of agricultural land to non-agricultural purposes between 2015–19. This decline in agricultural land—which a majority of Kashmiris still rely upon as the foundation of their economy—will disempower farmers, result in a loss of essential crops, make Kashmir less agriculturally self-sufficient, and create grounds for economic collapse in the near future. It is of course, only when Kashmiris are economically devastated that India's job in securing their land will be made even easier.

Alongside the destruction of agricultural land, the Indian government has also been charged with "ecocide" in Kashmir, which, "masked under the development rhetoric . . . destroys the environment without care, extracting resources and expanding illegal infrastructure as a way of contesting the indigenous peoples' right of belonging and using the territory for their own gain." During the lockdown in late 2019, the valley saw unprecedented forest clearances. In June 2020, the Jammu & Kashmir Forest Department became a government-owned corporation, allowing it to sell public forest land to private entities, including to Indian corporations. The rush to secure and extract Kashmir's resources has typically come at an immense cost to the region's vulnerable ecology, prompting local activists' fears that a lack of accountability will almost certainly exacerbate the climate crisis in South Asia. Just as Israel has secured control over Palestinian resources, India's stranglehold of Kashmir's natural resources and interference with the environment will ultimately make Kashmiris dependent on the Indian state for their livelihoods.

All of these shifts in land use reflect the "Srinagar Master Plan 2035," which "proposes creating formal and informal housing colonies through town planning schemes as well as in Special Investment Corridors," primarily for the use of Indian settlers and outside investors. Indeed, the Indian government has signed a series of MOU's with outside investors to alter the nature of the state by building multiplexes, educational institutions, film production centers, tourist infrastructure, Hindu religious sites, and medical industries. Kashmiri investors are no competition for massive Indian and external corporations and have a fundamental disadvantage in investing in land banks that the government has apportioned toward these purposes. Back to back lockdowns have resulted in massive economic losses for Kashmir's industries, including tourism, handicrafts, horticulture, IT, and e-commerce. Furthermore, "as with other colonial powers, Indian officials are participating in international investment summits parroting Kashmir as a 'Land of Opportunity', setting off a scramble for Kashmir's resources, which will cause further environmental destruction." India has always kept a close eye on Kashmir's water resources and its capabilities to generate electricity, while intentionally depriving Kashmir of the electricity it produces.

As more economic and employment opportunities are opened up to Indian domiciles, Kashmiris will also be deprived of what little job security they had. In sum, "neoliberal policies come together with settler colonial ambitions under continued reference to private players, industrialization and development, with the 'steady flow of wealth outwards.'"

Azad Essa, Hostile Homelands: The New Alliance Between India and Israel

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Liu Cixin’s science fiction novel The Dark Forest—part of the popular Three-Body Problem series recently serialized by Netflix—humanity is faced with the prospect of an alien invasion. The extraterrestrials are on their way to conquer Earth but are still light years away; humanity has hundreds of years to prepare for their hostile arrival.

Amid a need to bolster defense spending globally and, crucially, to foster innovation across the entire world, representatives of the global south make a proposal at the United Nations. Developing countries demand a universal waiver of intellectual property protections on inventions relevant to defense to enable them to develop their own technologies and contribute to planetary fortification. In Liu’s story, the global south’s call meets staunch opposition from wealthier states, which veto the proposal. Although set in an imagined future, Liu’s point resonates clearly in our own time.

The most recent parallel is the global vaccine hoarding that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic.

At the height of the emergency, rich countries bought up and hoarded COVID-19 vaccine supplies, which left many developing countries unable to obtain sufficient vaccines during 2021-22. Even when they arrived, donations of leftover doses from high-income countries were often too close to their expiration dates for developing countries to actually use them.

Global south states sought to build up their own secure vaccine production capacity but were stymied. Critically, vaccine manufacturers, such as Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech, refused to share IP-protected technology with World Health Organization (WHO) initiatives, such as C-TAP and the mRNA vaccine technology transfer hub, that were attempting to create a network of distributed vaccine production. It is estimated that such hoarding cost more than 1 million lives in developing states.

Remarkably, the global south saw this coming. Even before a single COVID-19 vaccine had been administered, developing countries accurately anticipated that they would be left at the back of the line for supplies. Burned by the experience of HIV/AIDS medicine shortages in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the global south predicted similar inequities occurring during the COVID-19 crisis—and they tried to act to prevent this.

In October 2020, this foresight motivated developing countries, led by South Africa and India at the World Trade Organization (WTO), to propose an international waiver of IP protections—known as a TRIPS waiver—on COVID-19 vaccines, treatments, and other health technologies. Much as in Liu’s story, the global north firmly rejected the proposal, leading to a delayed and watered-down WTO decision in June 2022 that I, and other academic experts, argued was too little, too late.

Crucially, we can observe the same pattern emerging yet again in the current negotiations over the WHO Pandemic Accord. Just like Liu’s vision of humanity preparing for an inevitable alien invasion but unwilling to share technologies globally, the world remains stuck in a doom loop. Another pandemic is foreseeable. A new treaty could provide a way for the international community to learn the lessons of COVID-19 and boost pandemic preparedness. Yet the world is making the same mistakes all over again.

Given the failures of the WTO process, experienced commentators such as Ellen ‘t Hoen anticipated that shifting the debate to WHO could help ensure that similar inequalities do not arise during the next pandemic. Many hoped that WHO, with its overriding focus on global health, would be a more receptive forum to the global south’s equity concerns than the WTO, which prioritizes IP via TRIPS, one of its foundational 1995 agreements.

However, thus far, the negotiations have been hampered by the same issue that blighted the WTO TRIPS waiver process: Rich states are unwilling to agree to any potential pandemic-related limitation of international IP rights or to expand IP flexibilities to include nonvoluntary options such as a mechanism for the compulsory licensing of trade secrets on pharmaceutical manufacturing processes needed for scaling up production of pandemic products.

Broadly speaking, developing countries want terms that would mandate technology transfer of key health technologies, such as vaccines, to the global south. Rich countries decry this suggestion, claiming it could undermine IP rights.

Hence, wealthy nations are balking at the use of progressive language on the compulsory use of IP in Article 11 of the draft accord. Instead, the U.S. government emphasizes supporting voluntary agreements—without acknowledging that the voluntary systems, including COVAX, failed to provide for the needs of citizens in many global south countries during the COVID-19 era.

In these negotiations, several key parties, such as the European Union and the United Kingdom, argue that a WHO treaty cannot deal with IP issues because that would equate to trespassing on rules that the WTO created. This back-and-forth between the WTO and WHO reflects an asymmetric power game that the global south is not well placed to win.

With no movement on IP, developing countries seem less willing to agree on a rare point of leverage, namely, the terms of Article 12, which addresses pathogen access and benefit-sharing. Put simply, developing countries are concerned that if they agree to terms on restriction-free sharing of pathogens with pandemic potential, without reciprocal guarantees of technology-sharing and health product distribution, they will be left at the back of the line again in the next pandemic.

Wealthy countries may be succeeding at reducing this leverage; recent news reports suggest that detailed provisions on pathogen-sharing may be shifted to a separate instrument.

It seems that for rich states, property is sacrosanct; global health is not. Yet, rather than property, it is worth recalling that patents were originally considered to be a form of state-granted privilege. In the 19th century, industrial states viewed IP not as an instrument of free trade but rather as a form of trade protectionism.

This idea of IP as protectionist privilege remains a more accurate description of what global IP law is intended to achieve. Much as in Liu’s novel, the stark reality is that there is no circumstance—not a new pandemic, not even an alien invasion—in which the global north would be willing to give up its protectionist privileges by sharing its technology with the global south.

With the WTO in decline and the WHO multilateral process in trouble, the global south may have to examine alternative options for building up pandemic preparedness. Intriguingly, Netflix’s 3 Body Problem envisages this. Unlike in the book, on TV the U.N. resolution for open technology-sharing is never even proposed.

Instead, a Mexican national who happens to be the chief scientific officer of a cutting-edge nanotech company becomes frustrated by Western corporate-military obstructionism and decides to upload all her London-based employer’s source code and trade secrets to open-source platforms with the aim of assisting developing countries to produce the technology. She even includes a downloadable guide on how to copy the functionality of the technology while avoiding IP infringement.

This fictional feint away from the multilateral forum and toward individual decision-making parallels real-world moves toward open-source biotech. This approach has been pioneered by Peter Hotez and Maria Elena Bottazzi of Baylor University, who created the patent-free COVID-19 vaccine Corbevax. They successfully transferred the vaccine technology openly to producers in Botswana and India. Meanwhile, the WHO mRNA hub at Afrigen in South Africa led by Petro Terblanche is encouraging open south-south collaboration on new vaccine technologies.

If the Pandemic Accord negotiations falter before the World Health Assembly begins on May 27 or they fail to produce a just treaty, efforts such as these will take on even greater importance. An inequitable Pandemic Accord will signal that Liu was right: The global north will continue to hoard technologies even in the face of looming Armageddon, and south-south collaboration on producing health technologies may be the only way forward for enhancing global pandemic preparedness.

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

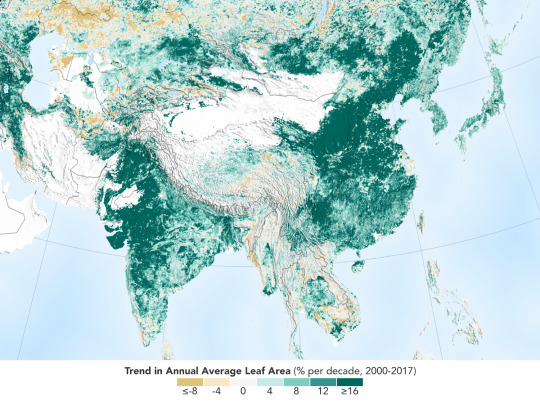

Human Activity in China and India Dominates the Greening of Earth, NASA Study Shows and presented with map.

Over the last two decades, the Earth has seen an increase in foliage around the planet, measured in average leaf area per year on plants and trees. Data from NASA satellites shows that China and India are leading the increase in greening on land. The effect stems mainly from ambitious tree planting programs in China and intensive agriculture in both countries.

The world is literally a greener place than it was 20 years ago, and data from NASA satellites has revealed a counterintuitive source for much of this new foliage: China and India. A new study shows that the two emerging countries with the world’s biggest populations are leading the increase in greening on land. The effect stems mainly from ambitious tree planting programs in China and intensive agriculture in both countries.

The greening phenomenon was first detected using satellite data in the mid-1990s by Ranga Myneni of Boston University and colleagues, but they did not know whether human activity was one of its chief, direct causes. This new insight was made possible by a nearly 20-year-long data record from a NASA instrument orbiting the Earth on two satellites. It’s called the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer, or MODIS, and its high-resolution data provides very accurate information, helping researchers work out details of what’s happening with Earth’s vegetation, down to the level of 500 meters, or about 1,600 feet, on the ground.

Taken all together, the greening of the planet over the last two decades represents an increase in leaf area on plants and trees equivalent to the area covered by all the Amazon rainforests. There are now more than two million square miles of extra green leaf area per year, compared to the early 2000s – a 5% increase.

“China and India account for one-third of the greening, but contain only 9% of the planet’s land area covered in vegetation – a surprising finding, considering the general notion of land degradation in populous countries from overexploitation,” said Chi Chen of the Department of Earth and Environment at Boston University, in Massachusetts, and lead author of the study.

An advantage of the MODIS satellite sensor is the intensive coverage it provides, both in space and time: MODIS has captured as many as four shots of every place on Earth, every day for the last 20 years.

“This long-term data lets us dig deeper,” said Rama Nemani, a research scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center, in California’s Silicon Valley, and a co-author of the new work. “When the greening of the Earth was first observed, we thought it was due to a warmer, wetter climate and fertilization from the added carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, leading to more leaf growth in northern forests, for instance. Now, with the MODIS data that lets us understand the phenomenon at really small scales, we see that humans are also contributing.”

China’s outsized contribution to the global greening trend comes in large part (42%) from programs to conserve and expand forests. These were developed in an effort to reduce the effects of soil erosion, air pollution and climate change. Another 32% there – and 82% of the greening seen in India – comes from intensive cultivation of food crops.

Land area used to grow crops is comparable in China and India – more than 770,000 square miles – and has not changed much since the early 2000s. Yet these regions have greatly increased both their annual total green leaf area and their food production. This was achieved through multiple cropping practices, where a field is replanted to produce another harvest several times a year. Production of grains, vegetables, fruits and more have increased by about 35-40% since 2000 to feed their large populations.

How the greening trend may change in the future depends on numerous factors, both on a global scale and the local human level. For example, increased food production in India is facilitated by groundwater irrigation. If the groundwater is depleted, this trend may change.

“But, now that we know direct human influence is a key driver of the greening Earth, we need to factor this into our climate models,” Nemani said. “This will help scientists make better predictions about the behavior of different Earth systems, which will help countries make better decisions about how and when to take action.”

The researchers point out that the gain in greenness seen around the world and dominated by India and China does not offset the damage from loss of natural vegetation in tropical regions, such as Brazil and Indonesia. The consequences for sustainability and biodiversity in those ecosystems remain.

Overall, Nemani sees a positive message in the new findings. “Once people realize there’s a problem, they tend to fix it,” he said. “In the 70s and 80s in India and China, the situation around vegetation loss wasn’t good; in the 90s, people realized it; and today things have improved. Humans are incredibly resilient. That’s what we see in the satellite data.”

This research was published online, Feb. 11, 2019, in the journal Nature Sustainability.

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

Biotechnology and the future of humanity

The End Of Diversity

GM technology is also set to plunge countless thousands of people into poverty by using GM plants or tissue cultures to produce certain products which have up until now only been available from agricultural sources in the majority world. For example, lauric acid is widely used in soap and cosmetics and has always been derived from coconuts. Now oilseed rape has been genetically modified to produce it and Proctor & Gamble, one of the largest buyers of lauric acid, have opted for the GM source. This is bound to have a negative effect on the 21 million people employed in the coconut trade in the Philippines and the 10 million people in Kerala, India, who are dependent on coconuts for their livelihood. Millions of smallscale cocoa farmers in West Africa are now under threat from the development of GM cocoa butter substitutes. In Madagascar some 70,000 vanilla farmers face ruin because vanilla can now be produced from GM tissue cultures. Great isn’t it? 70,000 farming families will be bankrupted and thrown off the land and instead we’ll have half a dozen factories full of some horrible biotech gloop employing a couple of hundred people. And what will happen to those 70,000 families? Well, the corporations could buy up the land and employ 10% of them growing GM cotton or tobacco or some such crap and the rest can go rot in some shantytown. This is what the corporations call ‘feeding the world’.

Poisoning the earth and its inhabitants brings in big money for the multinationals, large landowners and the whole of the industrial food production system. Traditional forms of organic, small-scale farming using a wide variety of local crops and wild plants (so-called’ weeds’) have been relatively successful at supporting many communities in relative self-sufficiency for centuries. In total contrast to industrial capitalisms chemical soaked monocultures, Mexico’s Huastec indians have highly developed forms of forest management in which they cultivate over 300 different plants in a mixture of gardens,’ fields’ and forest plots. The industrial food production system is destroying the huge variety of crops that have been bred by generations of peasant farmers to suit local conditions and needs. A few decades ago Indian farmers were growing some 50,000 different varieties of rice. Today the majority grow just a few dozen. In Indonesia 1,500 varieties have been lost in the last 15 years. Although a plot growing rice using modern so-called ‘High Yielding Varieties’ with massive inputs of artificial fertilisers and biocides produces more rice for the market than a plot being cultivated by traditional organic methods, the latter will be of more use to a family since many other species of plant and animal can be collected from it. In West Bengal up to 124 ‘weed’ species can be collected from traditional rice fields that are of use to farmers. The sort of knowledge contained in these traditional forms of land use will be of great use to us in creating a sustainable future on this planet; it is the sort of knowledge the corporations are destroying to trap us all in their nightmare world of wage labour, state and market.

#biotech#classism#ecology#climate crisis#anarchism#resistance#community building#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#revolution#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate#anarchy works#environmentalism

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Which Are The Best Forest Products In India?

India is making the best use of its forests. The country has the largest forest based industries in the world, and most of its forest products are exported to foreign markets. India produces approximately 2 million tons of dyes every year from red sander (bright red), Khair (chocolate), flowers of Palas, fruits of Mallotus phillipensis, the bark of wattle, and roots of Morinda tinctoria. This production makes dyes one of the leading forest products industry in the country.

#forest based industries#forest products industry#forest products in India#shellac export promotion council#forest products manufacturers in India

0 notes

Text

Good News - April 1-7

Like these weekly compilations? Support me on Ko-fi! Also, if you tip me on here or Ko-fi, at the end of the month I’ll send you a link to all of the articles I found but didn’t use each week - almost double the content! (I’m new to taking tips on here; if it doesn’t show me your username or if you have DM’s turned off, please send me a screenshot of your payment)

1. Three Endangered Asiatic Lion Cubs Born at London Zoo

“The three cubs are a huge boost to the conservation breeding programme for Asiatic lions, which are now found only in the Gir Forest in Gujarat, India.”

2. United Nations Passes Groundbreaking Intersex Rights Resolution

“The United Nations Human Rights Council has passed its first ever resolution affirming the rights of intersex people, signaling growing international resolve to address rights violations experienced by people born with variations in their sex characteristics.”

3. Proposal to delist Roanoke logperch

“Based on a review of the best available science, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) has determined that the Roanoke logperch, a large freshwater darter, is no longer at risk of extinction. […] When the Roanoke logperch was listed as endangered in 1989, it was found in only 14 streams. In the years since, Roanoke logperch surveys and habitat restoration have more than doubled the species range, with 31 occupied streams as of 2019.”

4. Fully-Accessible Theme Park Reopens Following Major Expansion

“Following the $6.5 million overhaul, the park now offers [among other “ultra-accessible” attractions] a first-of-its-kind 4-seat zip line that can accommodate riders in wheelchairs as well as those who need extra restraints, respiratory equipment or other special gear.”

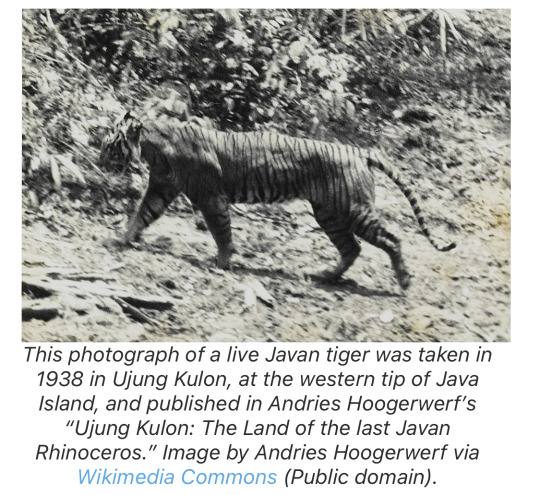

5. ‘The Javan tiger still exists’: DNA find may herald an extinct species’ comeback

“A single strand of hair recovered from [a sighting] is a close genetic match to hair from a Javan tiger pelt from 1930 kept at a museum, [a new] study shows. “Through this research, we have determined that the Javan tiger still exists in the wild,” says Wirdateti, a government researcher and lead author of the study.”

6. Treehouse Village: Eco-housing and energy savings

““The entire place is designed and built to meet the passive house standard, which is the most energy-efficient construction standard in the world,” says resident Wayne Groszko, co-owner of one of the units at Treehouse.”

7. 50 rare crocodiles released in Cambodia's tropical Cardamom Mountains

“Cambodian conservationists have released 50 captive-bred juvenile Siamese crocodiles at a remote site in Cambodia as part of an ongoing programme to save the species from extinction.”

8. The Remarkable Growth of the Global Biochar Market: A Beacon of Environmental Progress

“Biochar, a stable carbon form derived from organic materials like agricultural residues and forestry trimmings, is a pivotal solution in the fight against global warming. By capturing carbon in a stable form during biochar production, and with high technology readiness levels, biochar offers accessible and durable carbon dioxide removal.”

9. 'Seismic' changes set for [grouse shooting] industry as new Scottish law aims to tackle raptor persecution

“Conservation scientists and campaigners believe that birds such as golden eagles and hen harriers are being killed to prevent them from preying on red grouse, the main target species of the shooting industry. […] Under the Wildlife Management and Muirburn Bill, the Scottish grouse industry will be regulated for the first time in its history.”

10. White House Awards $20 Billion to Nation’s First ‘Green Bank’ Network

“At least 70 percent of the funds will go to disadvantaged communities, the administration said, while 20 percent will go to rural communities and more than 5 percent will go to tribal communities. […] The White House said that the new initiative will generate about $150 billion in clean energy and climate investments[…].”

March 22-28 news here | (all credit for images and written material can be found at the source linked; I don’t claim credit for anything but curating.)

#hopepunk#good news#lion#conservation#zoo#india#intersex#lgbt rights#human rights#fish#endangered#disability#accessibility#amusement park#tiger#big cats#extinction#extinct species#ecofriendly#affordable housing#energy efficiency#crocodiles#global warming#climate change#scotland#raptor#eagles#hunting#solar panels#solar energy

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The EARTHSHOT PRIZE AWARDS 2022 Ceremony will take place at the MGM Music Hall at Fenway on December 2nd.

THE FINALISTS:

FIX OUR CLIMATE:

44:01 (Oman) - According to the UN, removing CO2 is essential if we are to limit global warming. Oman-based 44.01 removes CO2 permanently by mineralising it in rock.

LanzaTech (USA) - Carbon, released into the atmosphere, heats the planet. LanzaTech are using bacteria to recycle carbon pollution into profitable and sustainable products.

Low Carbon Materials (United Kingdom) - Concrete is responsible for an extraordinary eight percent of the world’s CO2 emissions. Now, thanks to UK based LCM, production could soon go from unclean to green.

CLEAN OUR AIR:

Ampd Enertainer (Hong Kong) - The construction industry is difficult to decarbonise and is one of the biggest drivers of air pollution. Ampd Energy has revolutionised the way we power construction.

Mukuru Clean Stoves (Kenya) - Across Africa, 700 million people use traditional cookstoves, which emit harmful chemicals and lack safeguards. Mukuru Clean Stoves are different.

Roam (Kenya) - The electric vehicle revolution is coming to East Africa. Roam is bringing affordable, electric transport to one of the world’s fastest growing regions.

BUILD A WASTE-FREE WORLD:

City of Amsterdam, Circular Economy (The Netherlands) - In 2020, The City of Amsterdam committed to becoming a circular economy. By 2050, it aims to waste nothing and recycle everything.

Fleather (India) - Flowers cast into the Ganges river contain highly toxic pesticides. Phool used this floral waste to make a sustainable alternative to leather.

Notpla (United Kingdom) - 6.3bn tonnes of untreated plastic waste currently litter our streets and fill our seas. Notpla shows us that the future is not plastic, it’s seaweed.

PROTECT & RESTORE NATURE:

Desert Agricultural Transformation (China) - The climate crisis means more of the Earth will become inhospitable desert. But now, thanks to Desert Agricultural Transformation, barren landscapes are turning into lush, green oases.

Hutan (Malaysia) - In Malaysian Borneo, research organisation Hutan is working with the local community to develop a more harmonious coexistence between its wildlife and people.

Kheyti (India) - Eight in ten of the world's farmers are smallholders. Beset by climate-affected harvests, Kheyti's Greenhouse-in-a-Box is helping them reduce climate risk and increase yields.

REVIVE OUR OCEANS:

Indigenous Women of the Great Barrier Reef (Australia) - The Great Barrier Reef is under constant environmental threat. Now, the Indigenous Women of the Great Barrier Reef are empowering each other to protect critical ecosystems.

SeaForester (Portugal) - Human activities and the climate crisis are decimating underwater seaweed forests. Pål Bakken and the SeaForester team are on a mission to restore them.

The Great Bubble Barrier (The Netherlands) - Every year, more than 8 million tonnes of plastic ends up in the world’s oceans. The Great Bubble Barrier's solution intercepts plastic waste before it reaches the sea.

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Endangered Indian sandalwood. British war to control the forests. Tallying every single tree in the kingdom. European companies claim the ecosystem. Spices and fragrances. Failure of the plantation. Until the twentieth century, the Empire couldn't figure out how to cultivate sandalwood because they didn't understand that the plant is actually a partial root parasite. French perfumes and the creation of "the Sandalwood City".

---

Selling at about $147,000 per metric ton, the aromatic heartwood of Indian sandalwood (S. album) is arguably [among] the most expensive wood in the world. Globally, 90 per cent of the world’s S. album comes from India [...]. And within India, around 70 per cent of S. album comes from the state of Karnataka [...] [and] the erstwhile Kingdom of Mysore. [...] [T]he species came to the brink of extinction. [...] [O]verexploitation led to the sandal tree's critical endangerment in 1974. [...]

---

Francis Buchanan’s 1807 A Journey from Madras through the Countries of Mysore, Canara and Malabar is one of the few European sources to offer insight into pre-colonial forest utilisation in the region. [...] Buchanan records [...] [the] tradition of only harvesting sandalwood once every dozen years may have been an effective local pre-colonial conservation measure. [...] Starting in 1786, Tipu Sultan [ruler of Mysore] stopped trading pepper, sandalwood and cardamom with the British. As a result, trade prospects for the company [East India Company] were looking so bleak that by November 1788, Lord Cornwallis suggested abandoning Tellicherry on the Malabar Coast and reducing Bombay’s status from a presidency to a factory. [...] One way to understand these wars is [...] [that] [t]hey were about economic conquest as much as any other kind of expansion, and sandalwood was one of Mysore’s most prized commodities. In 1799, at the Battle of Srirangapatna, Tipu Sultan was defeated. The kingdom of Mysore became a princely state within British India [...]. [T]he East India Company also immediately started paying the [new rulers] for the right to trade sandalwood.

British control over South Asia’s natural resources was reaching its peak and a sophisticated new imperial forest administration was being developed that sought to solidify state control of the sandalwood trade. In 1864, the extraction and disposal of sandalwood came under the jurisdiction of the Forest Department. [...] Colonial anxiety to maximise profits from sandalwood meant that a government agency was established specifically to oversee the sandalwood trade [...] and so began the government sandalwood depot or koti system. [...]

From the 1860s the [British] government briefly experimented with a survey tallying every sandal tree standing in Mysore [...].

Instead, an intricate system of classification was developed in an effort to maximise profits. By 1898, an 18-tiered sandalwood classification system was instituted, up from a 10-tier system a decade earlier; it seems this led to much confusion and was eventually reduced back to 12 tiers [...].

---

Meanwhile, private European companies also made significant inroads into Mysore territory at this time. By convincing the government to classify forests as ‘wastelands’, and arguing that Europeans would improves these tracts from their ‘semi-savage state’, starting in the 1860s vast areas were taken from local inhabitants and converted into private plantations for the ‘production of cardamom, pepper, coffee and sandalwood’.

---

Yet attempts to cultivate sandalwood on both forest department and privately owned plantations proved to be a dismal failure. There were [...] major problems facing sandalwood supply in the period before the twentieth century besides overexploitation and European monopoly. [...] Before the first quarter of the twentieth century European foresters simply could not figure out how to grow sandalwood trees effectively.

The main reason for this is that sandal is what is now known as a semi-parasite or root parasite; besides a main taproot that absorbs nutrients from the earth, the sandal tree grows parasitical roots (or haustoria) that derive sustenance from neighbouring brush and trees. [...] Dietrich Brandis, the man often regaled as the father of Indian forestry, reported being unaware of the [sole significant English-language scientific paper on sandalwood root parasitism] when he worked at Kew Gardens in London on South Asian ‘forest flora’ in 1872–73. Thus it was not until 1902 that the issue started to receive attention in the scientific community, when C.A. Barber, a government botanist in Madras [...] himself pointed out, 'no one seems to be at all sure whether the sandalwood is or is not a true parasite'.

Well into the early decades of twentieth century, silviculture of sandal proved a complete failure. The problem was the typical monoculture approach of tree farming in which all other species were removed and so the tree could not survive. [...]

The long wait time until maturity of the tree must also be considered. Only sandal heartwood and roots develop fragrance, and trees only begin developing fragrance in significant quantities after about thirty years. Not only did traders, who were typically just sailing through, not have the botanical know-how to replant the tree, but they almost certainly would not be there to see a return on their investments if they did. [...]

---

The main problem facing the sustainable harvest and continued survival of sandalwood in India [...] came from the advent of the sandalwood oil industry at the beginning of the twentieth century. During World War I, vast amounts of sandal were stockpiled in Mysore because perfumeries in France had stopped production and it had become illegal to export to German perfumeries. In 1915, a Government Sandalwood Oil Factory was built in Mysore. In 1917, it began distilling. [...] [S]andalwood production now ramped up immensely. It was at this time that Mysore came to be known as ‘the Sandalwood City’.

---

Text above by: Ezra Rashkow. "Perfumed the axe that laid it low: The endangerment of sandalwood in southern India." Indian Economic and Social History Review 51, no. 1, pages 41-70. March 2014. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Italicized first paragraph/heading in this post added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

#a lot more in full article specifically about#postindependence indian nationstates industrial extraction continues trend established by british imperial forestry management#and ALSO good stuff looking at infamous local extinctions of other endemic species of sandalwood in south pacific#that compares and contrasts why sandalwood survived in india while going extinct in south pacific almost immediately after european conques#abolition#ecology#imperial#colonial#landscape#indigenous#multispecies#tiger#tidalectics#archipelagic thinking#intimacies of four continents#carceral geography#geographic imaginaries#haunted

220 notes

·

View notes

Text

...This is the problem with any climate policy, big or small: It requires an imaginative leap. While the math of decarbonization and electric mobilization is clear, the future lifestyle it implies isn’t always. Right-wing commenters sometimes seize upon this fact to caricature any climate policy as a forced retreat from modernity — Americans forced to live in ecopods — while on the left any accounting seems to cloud the urgency of the moment. A majority of emissions come from just 100 or so corporations, activists argue, a concentration of industrial production that, once decarbonized, could slash the footprint beneath every wall sconce and sandwich. Even if it were true, these arguments conveniently ignore one uncomfortable fact: Walmart, Exxon Mobil and Berkshire Hathaway didn’t burn that fuel on their own — we paid them to, or burned it ourselves, because the way we live depends on it. By any standard, American lives have become excessive and indulgent, full of large homes, long trips, aisles of choices and app-delivered convenience. If the possibilities of the future are already narrowing to the one being painted by science with increasing lucidity, it strains even the most vivid imagination to picture it widening again without a change in behavior.

This isn’t an American crisis alone. All around the world, nations have locked themselves into unsustainable, energy-intensive lifestyles... [...]

The problem of reducing our footprints further isn’t that we don’t have models of sustainable living; it’s that few exist without poverty. Imagine another typical household, this time somewhere in the rural tropics, like the Mara region in northwestern Tanzania. You live with five or six others, your husband, parents, grandmother and perhaps two kids, in a 700-square-foot house without electricity, maybe one you built by hand from sun-dried bricks. You cook with firewood and pay for 3G with the few dollars a day you make. All around you, people are clearing forests for corn and rice, damaging ecosystems that otherwise pull carbon from the air. To give your kids a better life, you move to the city, and as you make more money, you rent a bigger house, take more buses, buy an air-conditioner. All these improvements add to your quality of life, ticking you upward on the Human Development Index, but also expand your carbon footprint — the two being so closely tied they could be proxies. No matter your vocation or luck, the only real way for you to make your life better is to burn more fossil fuels. So you do — collectively elevating your country out of those with a footprint close to zero (Afghanistan, the Central African Republic) and into those around two tons: India, the Philippines.

This is the paradox at the heart of climate change: We’ve burned far too many fossil fuels to go on living as we have, but we’ve also never learned to live well without them. As the Yale economist Robert Mendelsohn puts it, the problem of the future is how to create a 19th-century carbon footprint without backsliding into a 19th-century standard of living. No model exists for creating such a world, which is partly why paralysis has set in at so many levels. The greatest crisis in human history may require imagining ways of living — not just of energy production but of daily habit — that we have never seen before. How do we begin to imagine such a household?

Late last year, I traveled to Uruguay in hope of glimpsing one possibility....

read more! [gifty link so you can read it without paywall]

59 notes

·

View notes