#history dissertation writer history dissertation writing

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

In Defense of the Phandom (Mostly): Dan, Phil, and Our Parasocial Social Club

Refer to my previous pinned post for an explanation of and outline for this project. Now that I'm done going through my old reblogs (god, it took forever), it's time to actually research and write this script! This will be my pinned post for the foreseeable future, so you can come back to it by clicking on my blog for the current status of this part of the process. (Note from February 15 - everything is on hold for now while I wrap up my dissertation!)

Script word count: 2,350 | Last updated: January 9, 2025

Research

Peer-reviewed or published literature: ⚫︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎ Social media, forum archives, and fanwork: ⚫︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎ The great rewatch: ⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎ Discussions with other phannies (hey! that could be you, if you want!): ⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎

Writing

Introduction, background, and conclusion sections: ⚫︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎ 2009-2013: ⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎ 2014-2018: ⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎ 2019-2025: ⚫︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎ Long tangents (fandom, RPF, and PSIs/PSRs): ⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎ Editing: ⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎⚪︎

More details below the cut!

Research → peer reviewed or published literature:

I read a few things (like Haidt's The Anxious Generation) while I was in the process of searching academic databases, but most of the 403 works I have saved to Zotero for this are currently unread. They're not all the same length or will take the same amount of time to read, so the completion proportion is just getting updated based on vibes. I'm absolutely not referencing all 403 of these things in the script - I just cast a wide net for materials I thought might be relevant. Furthermore, there are some things I didn't save that I know I'll be referencing, like some of the Pew Research Center's work in the early to mid 2010s on teenagers and technology, or the journalistic coverage of what got my school district in huge trouble in 2011.

Research → Social media and forum archives:

The collection of posts, art, and fic (other than mine) to reference in the video. For regular posts and art, especially by people who have long since abandoned their accounts or whose content went pretty viral, I feel comfortable just showing things in the video with credit as examples. For fic, I intend to just discuss trends more broadly and vaguely since, as a fic writer myself, I know we tend to get more flack and less acclaim for our work and therefore prefer to stay out of the spotlight. Let me know if you think I should handle this differently - the academic impulse is to credit sources and reproducible searches for every single thing you do, but that's definitely not best practice for phandom history since we have so much "forbidden" lore. I'll also be reading the IDB forum front-to-back, listening to things like the phandom podcast, reading the current generation of phanzines, and looking at recent (and historical, if anyone has any) surveys done of phannies within the community. I'm assuming those folks would appreciate credit and/or a shoutout.

Research → The great rewatch:

Rewatching everything DNP-related so I can talk about it from more recent memory (and read what's left of the original comments for DNP videos that are still up at their original locations). I know there's a playlist for this but I also know it's incomplete, so I have been doing some poking around myself and will probably continue to.

Research → Discussions with other phannies:

I read a few things (like Haidt's The Anxious Generation) while I was in the process of searching academic databases, but most of the 403 works I have saved to Zotero for this are currently unread. They're not all the same length or will take the same amount of time to read, so the completion proportion is just getting updated based on vibes. I'm absolutely not referencing all 403 of these things in the script - I just cast a wide net for materials I thought might be relevant. Furthermore, there are some things I didn't save that I know I'll be referencing, like some of the Pew Research Center's work in the early to mid 2010s on teenagers and technology, or the journalistic coverage of what got my school district in huge trouble in 2011. The first task is to sort that whole Zotero collection into more manageable sub-collections (on PSR on PSIs, on mental health, on YouTube platform history, etc), which is what I'm currently working on.

Writing → Introduction, background, and conclusion sections

See old pinned post for the outline. Will expand details here once research is mostly done (I plan to read and watch everything in the research section aside from talking to other phannies, then complete the script's rough draft, then talk to others on call, then integrate that with and finalize the script).

Writing → 2009-2013

See above.

Writing → 2014-2018

See above.

Writing → 2019-2025

See above.

Writing → Long tangents (fandom, RPF, and PSRs/PSIs)

See above. These tangents are kind of mini video essays in and olf themselves, so I may write them while I'm reading through my saved stuff in Zotero and before I rewatch all the DNP videos.

#dan and phil#phan#dnp#daniel howell#amazingphil#amy writes#i feel weird putting this in the main tags but given it's been TWO WEEKS WITHOUT A PHUPLOAD no one's gonna mind#as indicated - this is now pinned on this sideblog! more minor status updates will just be tagged “amy writes” so follow if you want those

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi sophie (again) one really quick note, the reason i read through your ENTIRE blog is because my dissertation is on facetious disorders portrayed and influenced by social media and the likes of such- it is literally a 250 page document about people like you. It's literally a part of my research to read long-winded things like this and write about them. My livelihood revolves around this. I don't expect to see a Dr. before your name, but you can damn well expect to see it before mine.

The only reason I sent that ask and wrote a targeted post was to get a response from you. The only reason. Had some writers block lol, I needed some material 😅😅

Another note to add to the grooming part was not about LGBTQ or transgender people as I am both myself. Please do not take it as a jab to your gender identity, and I apologize if it came off that way. It was in no way meant to insult you in that regard.

First, thanks for clarifying about the use of grooming. I don't mean to suggest you did intend it as a remark about my gender identity.

But I do think it's important to note in a "you are not immune to propaganda" way. Because I think, consciously or unconsciously, anti-endos have adopted transphobic talking points.

I assume and hope that this is unconscious. That rather than looking at how conservatives have used these talking points to harm queer communities and going "yeah, we can use that talking point too with these people we don't like," this absorption and repetition of these talking points is happening on a subconscious level. In which case, I think it's important to understand where they've originated and what the history is behind them.

As well as what misusing these terms normalizes. Because repeating them does contribute to a culture that is okay with using "grooming" this way to associate people they don't like with child abusers.

Now, allow me to first commend you on starting work on your dissertation so early. Working on it at just 20 is quite impressive indeed.

Although I have to question the subject matter.

A factitious disorder is when somebody is faking a disorder or pretending to have a disorder. It seems strange that you would seek to use examples of people who do not actually have a disorder and are not claiming to.

Even if endogenic systems were lying, unless they're presenting themselves as having a disorder they weren't, they wouldn't qualify for criterion B.

If you do want to write about people who have plural experiences without having trauma or a disorder, you might want to actually read my studies and research page. I'm sure that you could find stuff there that could help you on your journey.

And if you plan on writing about tulpamancy, specifically, Dr. Samuel Veissiere's Variety of Tulpa Experiences is probably most useful in understanding the tulpamancy community and viewpoints on the practice.

I would also recommend Learning to Discern the Voices of Gods, Spirits, Tulpas, and the Dead, as it offers a great comparison between tulpamancy and other forms of non-pathological voice hearing.

I imagine that these studies are much more productive uses of your time than scrolling through over 11,000 Tumblr posts, and would look better as sources in your dissertation.

Finally, if you are committed to doing a dissertation on factitious disorder, I would highly advise learning how to spell factitious. Because it's not "facetious" disorders, and spelling it that way might look a bit awkward on your dissertation about factitious disorder.

#syscourse#psychology#psychiatry#pro endogenic#pro endo#dissertation#sysblr#multiplicity#factitious disorder#systems#system#tulpamancy#tulpa#system stuff#systemscringe#r/systemscringe#systempunk#syspunk#actually plural#actually a system

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

🚨 I’ve Discovered the Block Button🚨

A Revolutionary Tool in the Art of Telling People to Shut the Fck Up—Permanently*

Welcome to the Golden Age of Digital Darwinism

Ladies, gentlemen, and intellectual warlords of the internet, today marks a revolutionary discovery in my already lethal arsenal of online dominance.

I, a humble yet undeniable force of nature, have discovered the Block Button. And with it, I have achieved inner peace, unparalleled power, and the ability to instantly euthanize weak arguments with a single click.

📌 THE ERA OF SUFFERING IN THE DM TRENCHES IS OVER

Once upon a time, I graciously tolerated the digital equivalent of a flatulent toddler having a tantrum in my inbox.

Every day, the same weak-wristed goons would show up: ❌ The angry reply guy who just got his worldview suplexed into the dirt. ❌ The professional victim crying about "tone" because facts hurt their feelings. ❌ The self-righteous dissertation writer who demands "a debate" but gets winded halfway through a sentence. ❌ The desperate white knight who thinks he’s earning feminist coochie coupons by crying “misogyny” at me in the hopes that someone, somewhere, will touch his limp, trembling hand.

🚨 For too long, I suffered in silence. 🚨 For too long, I watched these emotionally unstable disasters fling their word vomit into my DMs.

But no more.

Because I have discovered the single greatest tool in digital history.

🚀 The Block Button. 🚀

📌 THE BLOCK BUTTON: A MASTERPIECE OF HUMAN INNOVATION

This divine gift of modern technology allows me to evaporate weaklings into the void with the same ease as flicking lint off my sleeve.

With a single ruthless, efficient, and merciful action: 📌 Their cries are silenced. 📌 Their fragile egos are left screaming into the abyss. 📌 Their Twitter dissertations and unreadable copypasta essays become meaningless dust in the wind.

👉 Gone. Just like that. 👉 No arguments. No discussions. No prolonged suffering.

💀 They cease to exist in my digital kingdom. 💀

And the best part?

📢 They can still see me. 📢 They can still rage. 📢 But they can no longer interact.

I exist in their minds like a ghost they can never exorcise. I live in their subconscious like an unpaid bill they forgot about. I haunt them like the existential dread of knowing they will never, ever win.

📌 COMMON TYPES OF BLOCKED WASTES OF DATA

Now that I have ascended into a realm of peace and power, I have classified the most common creatures that get yeeted into the ether via THE BLOCK.

1️⃣ The Keyboard Warrior Who Writes Essays But Can’t Read a Room

This one needs you to read his 14-paragraph, Oxford comma-abusing manifesto.

His entire argument hinges on misinterpreting what you said and replacing it with strawman nonsense.

Block. Now his dissertation has no audience.

He will read it to himself in the dark, alone, like an unpaid Shakespearean actor screaming into his mirror.

2️⃣ The Pretentious Intellectual Who Overuses Words They Don't Understand

If I had a dollar for every time a “debate bro” misused "fallacious" in a sentence, I'd have fuck-you money.

Block. No more free lessons in literacy.

3️⃣ The “I’m Just Asking Questions” Gaslighter

He doesn't want answers.

He wants to drag you into an infinite black hole of pointless back-and-forths because he thrives on wasting time.

Block. Let him “ask questions” into the void.

4️⃣ The Clown Who Can't Let Sh*t Go

3 weeks later, he’s still mad.

5 months later, he’s still writing Tumblr posts about it.

A year later, he mentions it in therapy.

Block. End the saga.

5️⃣ The “Just Take the L” Guy Who Won’t Shut Up

My guy, I already won. You’re still replying.

Block. Your letters are returned to sender.

📌 THE DIGITAL LAWS OF BLOCKING: WHEN, WHY, AND HOW TO YEET WITHOUT MERCY

🚀 WHEN TO BLOCK: ✔ When their brain cells collapse under the weight of a factual statement. ✔ When their response reads like a meth-fueled fever dream. ✔ When they’re so desperate for your attention, they’ll reply to their own replies. ✔ When they’re an adult acting like a caffeinated 12-year-old on Xbox Live chat.

🚀 WHY TO BLOCK: 📌 Because your mental real estate is worth more than the trailer park in their brain. 📌 Because your time is finite, and their nonsense is infinite. 📌 Because sometimes, hitting "mute" isn't enough—they need to be THROWN INTO THE VOID.

🚀 HOW TO BLOCK WITH STYLE: ✔ No announcement. No preamble. Just click. ✔ Don’t tell them you’re blocking—it’s more fun when they realize it too late. ✔ Bonus points if you let them waste their best insults first.

They will think about it for WEEKS.

📌 THE AFTERMATH: WHAT HAPPENS WHEN YOU BLOCK A TROLL?

❌ They spiral. ❌ They cope. ❌ They stalk your page for weeks, hoping to find a sign that you regret it.

📢 Spoiler: You don’t.

💀 They are now digital ghosts, condemned to wander in rage and irrelevance.

📌 FINAL VERDICT: THE BLOCK BUTTON IS GOD’S WORK

I used to think I had to fight every fool who wandered into my DMs. I used to believe I owed explanations, counterarguments, and endless patience to people who didn’t deserve my time.

🚨 I was WRONG. 🚨

📢 The Block Button is a revolution in digital warfare. 📢 The Block Button is the nuclear option that ends stupidity in one click. 📢 The Block Button is the greatest invention of the 21st century, and I will use it without hesitation.

📌 FINAL CALL TO ACTION: BLOCK FREELY, BLOCK MERCILESSLY, BLOCK FOR PEACE

🔥 If you have ever blocked an idiot and felt instant relief, REBLOG. 🔥 If you love that a troll can still SEE YOU but can’t TOUCH YOU, FOLLOW [The Most Humble Blog]. 🔥 If you have ever laughed at a blocked person desperately trying to get your attention, COMMENT with your best "blocked and forgotten" story.

💀 You either learn to block, or you spend your life arguing with the doomed.

🚀 Choose wisely. 🚀

⚖️ LEGAL DISCLAIMER: This post is written for the purpose of artistic expression, cultural commentary, and psychological exploration of social and gender dynamics. It does not condone or encourage violence, harassment, or discrimination of any kind. Any references to power, strength, restraint, or critique are metaphorical, symbolic, and rooted in historical and cultural analysis. It’s a cultural mirror. If you feel offended, ask yourself if it’s from actual harm — or from seeing something you hoped no one would say out loud.

✨ TL;DR: If you're mad, it’s probably not because it’s wrong — it’s because you know it’s true.

#writing#cartoon#dora the explorer#writers on tumblr#horror writing#creepy stories#writing community#yeah what the fuck#funny post#funny stuff#lol#funny memes#funny shit#memes#humor#jokes#funny#tiktok#instagram#youtube#youtumblr#DigitalDarwinism#BlockButtonIsSacred#TrollsGetYeeted#FreeYourInbox#SilenceIsPower#OnlinePeacekeeping#NaturalSelectionInRealTime#NoTimeForClowns

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

for the fix writer meme

17. What highly specific AU do you want to read or write even though you might be the only person to appreciate it?

Thank you very much for the ask, friend!!! Questions are from this post.

17. What highly specific AU do you want to read or write even though you might be the only person to appreciate it?

This is so so so self-indulgent, but I occasionally have this vision of an Andor grad-school AU in which they're trying to unionize the T.A.s. Nemik is a bright-eyed philosophy Ph.D. student who just became a candidate; Vel is on her fellowship year in English, writing about queer fin de siècle Gothic and stressing out her girlfriend (Cinta, who's in the nurse's union and hangs with Teamster rep Brasso at the climbing/bouldering gym); Melshi is like, an incredibly exhausted seventh-year in history whose dissertation on the Chartist movement has gotten too theoretical and post-structural for his advisor (an old-school empiricist named Kino) and is never going to pass committee; and Cassian is actually a line cook at the best diner in town, but he ducked into a public lecture (by distinguished political scientist Luthen) one day to avoid his boss, and he asked a question so sharp and surprising he got taken for junior faculty: a mistaken assumption Cassian hasn't corrected at any of the dive-bar union-campaign meet-ups he's attended.

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

When are we going to talk about the concerning amount of people insisting 'the way that I wanted this story to go didn't happen! The writing is bad!!'

Cause I think we need to talk about the amount of people thinking 'thhe way that I wanted this story to go didn't happen! The writing is bad!!'

My God, you could write a whole dissertation on that phenom, honestly.

But, really, it can all be tracked back to a growing portion of Western populations insisting that all media has to be pre-chewed and easy to digest in order to be seen as 'good'.

"Why didn't the funny demon show have a happy ending?" Because the show is ultimately about relationships, both romantic and familial, and sometimes those relationships either go sideways or have unfulfilling arcs.

"Why is this historic romance novel so dark and unsettling? Romance novels are supposed to have HEAs!" Putting aside the elephant in the room of 'HISTORICAL' settings often dealing with unsettling aspects of human history, Romance as both a genre and a phenomenon doesn't always follow the same 1-2-3 formula of your average Lifetime Original Movie.

"I don't like the conflict in this danmei, why can't Asian writers just be better?!" Putting aside the elephant in the room of the anti-Asian bias that keeps cropping up in a lot of Western fandoms for Asian IPs, you do realize that narratives... Need conflict for the sake of a story, right?

... No, wait, of course these people don't: they're the ones pushing 'what I wanted to happen in this story didn't happen so that means the writing is BAAAAAD'.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

a story of the impact of groundbreaking representation in media

On April 30, 1997, I was eleven years old and at my godmothers' house for the night. I don't know how many remember but network tv during the week used to be a big deal. This is when families would sit down together and watch their favorite shows.

This evening I remember sitting on the couch and feeling something buzzing in the air. My godmothers' were so happy and excited about something, but I didn't really know what.

They put on Ellen and I remember brushing my Barbie dolls hair and an electric rush fill the silence of the room (outside of the tv of course).

"I mean, why can't I just say… I mean, what is wrong? Why, why do I have to be so ashamed? I mean, why can't I just… say the truth, I mean, be who I am... I'm 35 years old, I'm so afraid to tell people, I mean, I just… Susan, I'm gay."

And in that moment Ellen Degeneres made history. I was too young to understand the impact, but it was still strong enough for me to remember, 27 years later, the impact that had on the lives of two of the most important women in my life. Their clasped hands and tears of joy have made a marked impression in my life and I consider one of the most defining moments of my life.

We had this moment again. We had, on network tv, which is still extremely censored and conservative by the way, a ~33 year old man discover another part of what makes him so special. It was treated as such, like they understood the impact. This ~33 year old man was also masc and a firefighter--a career which is regressive in many areas and there are many, many firefighters in the closet--and his love interest was another masculine gay man who also happened to be a firefighter. We had wonderful friendship representation and development.

Then... all that was undone in 42 minutes by lazy, reductive storytelling. Writing that undid all that beauty in under three minutes. And that is the probably the biggest slap in the face.

They used harmful and reductive stereotypes in a breakup that wasn't even properly plotted for the story structure they use. So, yes, I am going to remain angry at the writers of 9-1-1 for a while.

I will always love Buck and I will always love the characters of 9-1-1. They also made me love Tommy. If the intention was to always just have him only be a chapter in his story, that's okay, but the chapter didn't need to be a dissertation, just to leave us with a cliff noted eight grade book report.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Illegitimate Media, Part II

In my last post, I shouted out Abigail De Kosnik’s dissertation, Illegitimate Media: Race, Gender, and Censorship in Digital Remix Culture. De Kosnik’s goal for this project was “to place African Americans and women at the beginning of the history of popular digital culture, to ensure that they are credited with the invention and popularization of the earliest forms of digital remix culture.” She also wants to explain “why their genres of remix have been subjected to so much censorship and restraint, from outside and in.” Notably, De Kosnik spends considerable time examining censorship from the inside–that is, she looks at the ways in which female media fans have not just fought off censorship from outside, but negotiated their attempts to censor each other. She notes the early adoption of the convention of warnings–which were meant to warn readers away:

Note, in Examples 2 and 3, the word “WARNING” in capital letters leading off the posts, and the series of repetitive, emphatic statements making clear the fact that the stories contain sexual content, and the defensive phrases that seem to anticipate a reader’s negative reaction to the sexual content: (in Example 1) “I really can’t take any complaints seriously if you fail to heed this warning”; (in Example 2) “if you don’t like that, too bad. You don’t have to read it if you don’t want to”; (in Example 3) “If that bothers you, do NOT read this story...Don’t flame me if you’re silly enough to go ahead and read it after I warned you, and then get offended by it.” These prefaces put the onus of the responsibility for the reader’s enjoyment of the erotic fiction squarely on the reader: (in Example 1) “Caveat lector,” or “Reader beware.” In all three examples of headers, the writers do not advertise the appeal of the sexual fantasies they have taken the trouble to create; they do not promise the reader pleasure. They do just the opposite: they address the reader with the assumption that the reader will find these stories about sexual gratification unpleasing, and these headers constitute pre-emptive strikes in the expected blame game that will ensue from the reader’s discomfort and displeasure. These headers state, It will not be my, the writer’s, fault for writing what I should not have if you are made angry or uncomfortable by this sexually graphic story, instead it will be your, the reader’s, fault for reading what you should not have (148).

That said, De Kosnik also acknowledges that “every severe warning can also be read as an invitation,” as “sly and flirtatious come-ons, meant to intrigue and entice” the reader. She thinks that the history of erotic fanfiction (and the warnings thereof) speaks very specifically to the feminist pornography wars of the 1980s - which might be useful to think about as we consider how our own use of tags and warnings speaks to our own historical moment.

--Francesca Coppa, Fanhackers volunteer

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

[same article as this post, different excerpt]

Emma Saltzberg: When Israeli state actors were trying to influence the American Jewish conversation, what did that look like? What kind of activism were they targeting?

Geoffrey Levin: One of the main figures in the book is Don Peretz, a pacifist-leaning American Jew who volunteered to help displaced Palestinian Arabs in Israel in 1949, wrote the first dissertation on Palestinian refugees, and later became a major scholar on the subject. In 1956, the AJC hired Peretz to be their first Middle East consultant, and he wrote pamphlets for them about Arab refugees that did not rule out return as part of a possible solution. Later that year, Israeli diplomats pushed the AJC to fire him. The AJC compromised by allowing Peretz’s writings for them to be looked over—or censored—by the Israelis. Eventually, the AJC did push Peretz out. Israeli diplomats also successfully lobbied the London-based Jewish Chronicle, as well as several mainstream American Jewish publications, to disaffiliate with their longtime writer William Zukerman because he repeatedly wrote about the Palestinian refugee problem and was upset about refugees not being able to return.

A lot of these figures they went after, including Zukerman and Peretz, were not radical anti-Zionists. But Israeli diplomats were actually more concerned about these people who were operating within the American Jewish mainstream, because during its early years Israel relied heavily on American Jewish financial and political support. And they were afraid that the American government might pressure Israel to accept a limited refugee return, which they opposed because they wanted to maintain a larger Jewish demographic majority and to avoid having to return land to its previous Arab owners. So they didn’t want the American Jewish community wavering on its opposition to that. As far as Israel was concerned, it was best if American Jews just didn’t talk about Palestinian refugees at all—unless they were repeating Israeli talking points.

ES: What about the CIA and Arab state actors? How were they trying to influence American discourse on Israel/Palestine?

GL: Surprisingly, one of the main reasons American Jews were thinking about Palestinian refugees in the mid-1950s is because this CIA-funded anti-Zionist organization called the American Friends of the Middle East (AFME) was raising awareness about the Palestinian cause. This was part of the Eisenhower administration’s effort to create more political space to push Israel to make concessions to Egypt to help them court Arab nationalist Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser as an anti-Communist ally. In the US, AFME ran propaganda campaigns against Zionism. Many of its members were white American Protestants, though AFME also sponsored the creation of the Organization of Arab Students. So the first national American Arab student organization was funded with CIA money, though the students didn’t know that; they were just advocating for their cause.

There were also Arab state actors who were advocating for Palestinians in the US; I focus on the work of Fayez Sayegh, who was running the Arab League office in the US for a short period in the mid-1950s. At that moment, there was a hope amongst some in the American foreign policy establishment and some more conservative Arabs—often Christian like Sayegh—that America and the Arabs would align to counter Soviet influence in the Middle East. But by the ’60s, and especially by the ’70s, that dream was falling apart as Cold War alliances solidified. And so you had Arab states and the Palestinians moving in an anti-US direction, turning toward Third World alliances and alignment with global anti-colonial struggles. In fact, In the early ’70s, that Arab student group that was first funded by the CIA ended up being monitored by the FBI.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

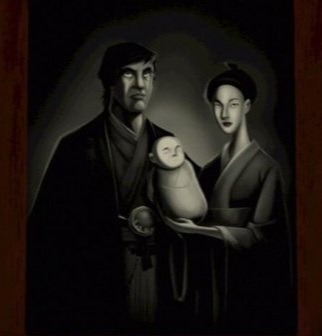

Adding More Backstory to Tang Shen

I wish 2012 had told us more about Tang Shen. Not much was told except that she was born in Fukuoka, was 1/4th Chinese, and was a woman both Splinter and Shredder were in love with.

Also, there's a line Shen says at one point, which involves her saying, "I can take care of myself; I've always have." Giving the idea, she grew up in tough circumstances. We never hear anything about her parents, if she was orphaned or not. We know her grandparents were present in her life, and I looked up information about the city of Fukuoka, which is stated to be a fairly safe place. I wish that line was explored more, but it just feels like the writers put it there for some brief moment of angst.

There was also a bit of writing inconsistencies. In season one, episode 26, there are these lines of dialogue I got from the episode's transcript when Splinter and Shredder are fighting

But then, in season 3, in the Tale of the Yokai episode, there's this scene

Yeahh, I believe I found a way to explain this in my rewrite of 2012, but for now, I want to talk about my rewrite of Shen.

I was thinking of making Shen a Taiwanese woman of 100% Chinese descent. She was really close to her father, but unfortunately, he died when she was still a child.

Shen's mother raised her and Shen's younger sister as a single mother with the help of Shen's older brother, who stepped up to provide for his family after their father died.

Shen was a very studious and hardworking young lady, but also a little bit rebellious as she was very set on the choices she made for herself, whether her mother approved or not.

She got accepted to Cambridge University, where she majored in history and minored in linguistics, as she had a passion for history like her father, and wanted to become a historian.

After she graduated from her undergraduate program, she entered her PhD. program for history, where in the last few years of said program, she worked part-time on her dissertation while also working as an English teacher in Japan.

During her time in Japan, she met Shredder and Splinter. Shen met Shredder first; they became friends, and soon both developed feelings for each other. When Shen tried to make a move, Shredder rejected it, as he wanted to focus on the future of the Hamato Clan and gain the approval of his adoptive father, Hamato Yuuta; he also wanted to respect her dream of becoming a historian, and not distract her from it. Shen was embarrassed but respected his decision and agreed just to be friends.

Shen and Splinter don't get together until a little bit later. Actually, when they first met, they didn't like each other at all as their first impression of each other wasn't great. However, they, of course, do come to respect each other after Splinter helped Shen when her car broke down at the side of the road. Shen and Splinter later become friends and then develop feelings for each other, which surprised both of them, especially Shen, as Splinter was someone she did not expect.

I like to think that as they spent more time together, Shen felt more comfortable talking about her passion and also introduced Splinter about the history of the Renaissance Painters.

She does graduate from her PhD. program, but also accidentally gets pregnant because the portrait Splinter has looked like a wedding photo.

I also thought about how Shen was able to find out about how brutal the war between the Hamato and Foot Clan before Splinter does, seeing how it involved the never-ending cycle of revenge. Finding that out, Tang Shen never wanted her daughter to get involved with ninjitsu.

Look at the way Shen looks at her baby daughter; she would've done anything for her.

She wanted Karai to have a normal life, and that's staying in my rewrite, but I also want to explain why she would push Splinter to leave ninjitsu to go to New York with her to raise their daughter; the history between both clans would play a big part with that, as well as her love for Splinter, but also Shen would still be traumatized from losing her father at a young age, and didn't want her daughter growing up without her father.

But unfortunately, Shen dies. I'm keeping Shen's death the same way it happened in the show, but yeah, that was my rewrite. Let me know what you guys think.

#tmnt 2012#teenage mutant ninja turtles 2012#tang shen#karai#hamato miwa#Splinter#shredder#hamato yoshi#Oroku Saki

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

I GOT MY DISSERTATION BACK AND IT'S A 70!! THAT'S A FIRST-CLASS GRADE! GOD I'M SO HAPPY I PUT SO MUCH BLOOD, SWEAT AND TEARS INTO A TOPIC THAT WAS REALLY FUCKING HARD AND IT. PAID. OFF!!! ALL OF MY EFFORT BORE FRUIT AND I'M ON TOP OF THE FUCKING WORLD RIGHT NOW! ALL OF THE MIND-MELTING READING ON THE NATURE OF A DEITY, ALL OF THE HOURS SITTING AT THAT TABLE WRITING EVERY DAY, ALL OF THE SCAVENGER HUNTING FOR RELEVANT BOOKS ON AN OBSCURE TOPIC IN THE LIBRARY - THIS WAS WORTH EVERY SINGLE MINUTE, EVEN WHEN IT STARTED TO SUCK OUT MY GODDAMN SOUL! WE'RE GONNA EAT DOMINO'S PIZZA TO CELEBRATE AND THEN WE'RE GOING TO THE CINEMA (THAT WAS ALREADY BOOKED, WASN'T EXPECTING MY MARK TO APPEAR TODAY) AND I'M GONNA SEE HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON WITH MY DAD!

Whoo, calming down now... I'm just so damn happy about this. I can't count how many hours I spent reading and writing. There's a reason we were advised to pick a topic we like - after a while, especially close to the end, it becomes tedious and mind-numbing and it feels like it'll never end. I'm glad I followed that advice, because I thoroughly enjoyed my subject and STILL felt worn down and bored during the final 2000-word stretch. At times, it felt like I'd never get there. It felt impossible. But I pushed through and came out on the other side.

The fact that we're seeing HTTYD today is pure coincidence, I had no idea when I'd see my grade and it just happened to be the same day. Somehow, it just seems thematically appropriate. I remember seeing the original film in the cinema 15 years ago, as a kid who was trying to find their way in the world and experiencing struggles at school and at home, feeling quite lost and hating myself (my autism was undiagnosed at the time, so I hadn't received the help I'd get later and felt that there was something fundamentally wrong with me, but I couldn't figure out why). I came out of that cinema changed forever, utterly fascinated by dragons, which later expanded to a special interest in all things mythological. I was already an avid writer, but the things I wrote about were definitely flavoured by this - I later wrote 7 books between the ages of 10 and 13 (ranging from 20k to 70k words, never published), all of which featured dragons in some capacity. Dragons also continue to appear in all of my longfics to this day, and even my Tumblr profile pic is a dragon!

Now, 15 years later, I'm going back to see HTTYD again. I'm an adult finding their way in the world, just discovering a niche industry I fit perfectly into, like I was made for it. I'm about to graduate with an Ancient History degree (still waiting on an exam and assignment mark, but I have faith in myself). I've found a volunteer job in my chosen field and am searching for a paid one. I just got my dissertation back with a fantastic grade. I've known about and been managing my autism for almost ten years, learning to regulate myself and harness the skillset that came with it. School and home troubles are far in the past, and those involved are no longer in my life. I have friends who support and encourage me to be who I want to be. I know who I am. Nothing was ever wrong with me. I'm proud of who I am, and I can proudly say I love myself and have never been happier than I have in these past six months. It all came full circle. A sad, lost child went to see a film that changed them forever. Now, an adult who is finding their place in the world is going to see it again, having come out on the other side of multiple struggles and become stronger. If I could go back in time and talk to my younger self, Lil Dap would be stoked to know they have a bright future ahead of them - that they're going to make it, no matter how hopeless life feels for them.

Wow, that all got a little deep there. Today is just a huge day for me. It feels like my whole life has built up to this moment, and I wouldn't have it any other way.

EDIT: Literally the second I posted this, I got one of my remaining marks back - another 70! Now I'm waiting on only one more mark to confirm I'll be graduating!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Quick Note on 'Jewface', Maestro and Oppenheimer

Given that my presence on this platform is filtered specifically through the lens of Jewishness in film, and that I wrote my undergraduate dissertation on the Jewish identity of Leonard Bernstein – the subject of Bradley Cooper’s controversial upcoming film, Maestro – I thought I’d weigh in on the current discourse.

For those who are unaware, one of the biggest films due to premier as part of this year’s autumn film festival season is Bradley Cooper’s Maestro. The film is said to be a non-traditional biopic of 20th century American composer Leonard Bernstein, focusing largely on his complex relationship with his wife, Felicia Montealegre. Controversy has arisen around the Netflix production due to images from the trailer featuring Bradley Cooper as Bernstein wearing an enlarged prosthetic nose. Voices within and outside Jewish communities have loudly criticised Cooper for caricaturing Jewishness, using the term ‘Jewface’ which describes the act of a goyische (non-Jewish) actor using prosthetics to make themselves look more like a cartoonish, imagined Jew.

While it is true that Bernstein did own a decent sized schnoz, the prosthetic utilised by Cooper is significantly bigger, and more defined than the nose was in reality. From a personal standpoint, I do find the use of this prosthetic to be pretty discomforting, but I think it speaks more to Cooper’s insecurity about the size of his own nose, which is a lot bigger than perhaps he would like to admit (and not too dissimilar to Bernstein’s actual nose!), than it does about his perception of Jews. That being said whether it was his intention to cartoonify Jewishness or not, Cooper has ruffled feathers in a way that is crass rather than substantive. Bernstein’s living relatives have come out in support of Cooper and his decision to use the prosthetic, saying that Bernstein would not have minded, but I think their statement rather misses the point. The nose is not about Bernstein himself, but about highly visible representations of a tiny minority that are stereotypical and incredibly reductive.

Funnily enough, however, Cooper’s use of ‘Jewface’ is the element of Maestro that bothers me the least. I have been fairly vocal since the film’s announcement about how I believe the production as a whole to be a pretty catastrophically bad idea. Leonard Bernstein is my number one creative hero – as a composer, public intellectual and educator, I don’t think there has been a single Jewish figure in American history who has had more of a positive impact on culture.

As I mentioned, I have written extensively about Bernstein in an academic context, and in researching him, it became clear to me just how vitally important his Jewish identity was to him throughout his life. It informed his music (even West Side Story, which was initially conceived as a story about Jews and Catholics on the Lower East Side of Manhattan), and his role as an educator (he often described his pedagogy as rabbinic in nature), and he was deeply, foundationally affected upon learning about the realities of the Holocaust which caused what he described as ‘aporia’, a state of being where he was too overwhelmed to write a single word for years. Bernstein’s complicated relationship to sexuality was also hugely significant in his life. There is still debate to this day about whether, given an open, accepting environment, he would have identified as a gay man or as bisexual. He had significant, passionate relationships with both men and women, and was an early major advocate for HIV/AIDS research.

My problem with Maestro is that I don’t have faith in Bradley Cooper as a writer/director, to sensitively depict these two massive aspects of Bernstein’s identity. Focusing on his most significant straight-passing relationship as the centre of a film called Maestro does not inspire confidence that the film won’t totally whitewash Bernstein’s Jewishness, or reduce his sexuality to the pain it caused his wife (in a similar way to other reductive music biopics like Bohemian Rhapsody or Rocketman). Cooper’s own identity is significant in that he is starting from a place of remove from the identity of his subject, which isn’t necessarily a dealbreaker, but when there are other filmmakers out there who are far better suited to a project like this, both from an identity perspective and a thematic one, it’s hard to justify why this project exists at all in its current form.

Some have pointed to the involvement of Steven Spielberg as a producer on the project as hope for better representation, but given that Cooper and Martin Scorsese – a filmmaker who I have criticised in the past for the didactic, Christian morality of his movies – are also credited producers, I don’t think it’ll make much difference. I’m more comforted by the involvement of Josh Singer (Spotlight, The Post) and his contribution to the screenplay, given his Jewishness and his work on thematically sensitive historical films.

I’m not writing off the film entirely just yet. I had similar worries about Oppenheimer, given the significance of the scientist’s Jewishness in his decision to start work on the bomb in the first place. Nolan and Cillian Murphy, thankfully, proved me wrong in the director’s decision to focus on the differing Jewish identities of Oppenheimer, Lewis Strauss, and I.I. Rabi, and the nuanced ways in which their characters were informed by Jewishness, as well as Murphy’s attention to detail in his performance. It’s certainly possible for non-Jewish filmmakers to consider Jewishness in a valuable way (see Todd Field’s Tar or Paul Thomas Anderson’s Licorice Pizza for a couple of recent examples), but the set-up of this project makes it hard for me to believe that Cooper is one such filmmaker.

To end with a little self-gratifying what-if, I thought I’d lay out what would be my ideal Bernstein biopic: a film centred around the relationship between Bernstein and his fellow queer, Jewish composer and mentor, Aaron Copland, the letters they wrote to one another, and the fallout of their brushes with McCarthyism which had vastly different outcomes. I would keep Cooper as Bernstein (without the prosthetics!) because he can convincingly play the man’s charm, I’d cast Michael Stuhlbarg as Copland, and get Todd Haynes to write and direct. Haynes is Jewish, gay, and has a great deal of experience directing sweeping, romantic, dark, and political films. He knows how to portray music on screen and has several masterful period-pieces under his belt, with Carol in particular as a shining example of complex, historical queer romance in America. Honestly, this would be my dream film project.

#blu ray#blu ray collector#blusforjews#cinema#cinephile#film#film tumblr#jewishness#jewishness in film#maestro#leonard bernstein#bradley cooper#jewface#antisemitism#oppenheimer#christopher nolan#todd haynes#michael stuhlbarg#aaron copland#biopic#music biopic#queerness#queer history#gay#bisexuality#lgbt representation

54 notes

·

View notes

Note

can we hear the code geass rant 👀

i'm not gonna do a dissertation with like perfect recall of my sources bc i haven't watched it since it aired (almost 20 years now. horrifying??) and i have no intention of putting myself through that again spoilers ahead

my number 1 problem with it is that, as a whole, this series just fundamentally hates women. like to the point where even my teenaged ass that had much more patience for casual misogyny back in the day was taken aback with a "hey what the fuck"- like i think a lot about the specific ways a lot of the female characters were just killed off in incredibly brutal ways for Shock and also mostly to just make the male leads sad for a little bit. (i really haven't seen a good reason for why shirley had to die and she had to die Like That) (and like she is far from the only one but her death was a Breaking Point for me) . or like. the general treatment of kallen- who got built up as a competent knight but then mostly just got sexually harassed and left to make sad faces at lelouch. it's just- i don't feel like any of the female characters got to achieve real agency (which hits esp weird in a series so concerned about Agency and Control) nunnally gets her own section bc it's just like. this horrible mix of ableism and misogyny. where like she literally gets written as and treated as a plot macguffin. i don't think the series would be fundamentally different if lelouch was looking after his mother's beloved pet dog (who might've gotten to say more let's be real here) or a family heirloom. the writers use her disabilities to objectify her- that is, to have the other characters and the world itself treat her as an object. and honestly seem deeply unconcerned with her inner life outside of "precious innocent widdle sister" the other female character that gets her own section is nina. who is genuinely and truly. the worst example of a psycho lesbian trope i have ever seen in my life. like just taps right into the predatory lesbian trope and doesn't bother giving her a personality other than Being A Creep and also Racism. and that's the only gay character. aside from the misogyny, i also just generally felt like the show focused harder on Shocking The Audience rather than coherent writing. (which y'know. hard to have coherent writing when you're deeply dedicated to never writing any of the female characters) i feel like a lot of the political messaging was hamstrung by the focus on audience-via-Lelouch's arrogant asshole power fantasies too and it has been like 20 years since i've seen it (and i also watched it having not known much about the political context), but i think there is something to be said about the way code geass decontextualizes actual historical patterns of colonization, particularly in regards to their own imperial history and related atrocities.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dr. William Thomas Valeria Fontaine (December 2, 1909 - December 29, 1968) taught philosophy at Lincoln University, Southern University, Morgan State College, and for twenty years at the University of Pennsylvania. He was born in Chester, Pennsylvania, the son of steelworker William Charles Fontaine and Mary Elizabeth Boyer. He graduated from Lincoln University and received his BA.

He taught part-time at Lincoln, and in his field of Latin authors, he taught a pioneering course in Negro history. He did graduate work in philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania, where he received a Ph.D, concentrating on the history of Roman thought. His dissertation was entitled Fortune, Matter, and Providence, a study of Ancius Severinus Boethius and Giordano Bruno.

He accepted a position at Southern University. He married Willa Belle Hawkins, a divorcee with two children.

In 1943 the army drafted him. He served at Holybird Signal Depot teaching literacy to Black draftees. He joined the faculty at Morgan State College as head of Psychology and Philosophy. He took a lectureship at Pennsylvania. He received a tenure-track appointment to begin that fall semester.

His concerns appeared in two notable publications. “The Mind and Thought of the Negro of the United States as Revealed in Imaginative Literature, 1876-1940,” and “Social Determination in the Writings of American Negro Scholars”.

He was diagnosed with active tuberculosis. He made a recovery for a decade when his disease was in remission. He was tenured and promoted to an associate professorship. He was one of the very rare African Americans teaching in the segregated white academy, and the only Black philosopher in the Ivy League. He won Pennsylvania’s sole teaching award in 1958.

The Civil Rights movement propelled him to take up questions of race in the US. He studied the movements of nationalism and anti-colonialism in Africa. His participation in the Conference on Negro Writers in Paris signaled this new line of thinking.

He completed Reflections on Segregation, Desegregation, Power, and Morals. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence #omegapsiphi

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joan Gordon

Reveling in Genre: An Interview with China Miéville

China Miéville was born on September 6, 1972, in Norwich, England, but has spent most of his life in London. King Rat (1998), his first novel, is a coming-of-age fantasy incorporating folk tales and drum’n’bass music into an action-packed quest. His second novel, Perdido Street Station (2000), which he wrote while working on his PhD, received a great deal of critical attention, winning both the Arthur C. Clarke Award and the British Fantasy Award, and being short-listed for the World Fantasy Award. The Scar (2002), his third novel, also very well received, is a stand-alone sequel to Perdido Street Station, taking place in the same world but with different characters. Miéville is working on a third stand-alone novel set in that world. He has published several short stories and novellas, and is presently an editor of Historical Materialism, serving as special editor of a recent issue on Marxism and Fantasy (10.4 [2002]). In May 2003, he was Guest of Honor, along with Carol Emshwiller, at WisCon, the feminist sf convention. A committed Marxist, he ran for British Parliament in 2001 as the Socialist Alliance candidate. The photo of him that appears on both Perdido Street Station and The Scar fairly represents his strong physical presence—tall, muscular, and brooding. The man himself, however, is soft-spoken, humorous, and self-deprecating. The interview which follows is based on an email dialogue conducted between March 2002 and August 2003. It represents the current interests of a writer already accomplished but still near the beginning of his career.

Joan Gordon: Would you describe your childhood and education?

China Miéville: There were three of us in my family: my mum, my sister Jemima, and me, a close-knit single-parent family. I met my father maybe four times, but never really knew him, and he died about 8 years ago. We lived in north-west London, in a working-class, ethnically-mixed area called Willesden (where King Rat opens).

My parents were hippies, and the story is that they went through a dictionary looking for a beautiful word to name me. They nearly called me Banyan, but flipped a few pages on and reached “China,” thankfully. The other reason they liked it is that “china” is Cockney rhyming slang for “mate.” People say “my old china,” meaning “my old mate,” because “china plate” rhymes with “mate.”

We used to go to a lot of museums and art galleries, and we used to watch an awful lot of TV. We were pretty poor (my mother trained to be a teacher, which even when she qualified didn’t mean a whole lot of money), but from the age of eleven, I went to private school on scholarships. I had a great childhood. I was a bit of a geek and a bit anxious, but I had plenty of friends and interests, mostly sf-related-RPGs [role-playing games], reading, drawing, writing—and later, politics.

When I was 16 I went to boarding school for two years, which I loathed. I went to Cambridge University [in 1991] to read English, but quickly changed to Social Anthropology, receiving my degree in 1994. Then I worked for a while as sub-editor on a computer magazine, did a Masters in International Law from the London School of Economics (receiving the degree in 1995), spent a year at Harvard, and then received a PhD in Philosophy of International Law in 2001.

My dissertation is entitled A Historical Materialist Analysis of International Law and the Legal Form. It’s a critical history and theory of international law, drawing extensively on the work of the Russian legal theorist Yevgeny Pashukanis. Its direct influence on my novels has been very slight. There’s a reference to jurisprudence in Perdido Street Station which is drawn from it, and there’s something about a form of maritime law in The Scar, but that’s about it. The thesis is really an expression of a much broader theoretical interest and approach, which in turn informs the fiction, so to that extent, they’re both infused with a shared outlook.

JG: What cultural influences shaped your writing?

CM: My sister and I watched a hell of a lot of TV, which is partly why I don’t buy the argument that it stultifies children’s imaginations—I think it depends almost entirely on the context in which you’re watching it. British children’s TV in the 1970s and early 1980s was extremely good, and these days I often realize that something I’m writing is a riff from that early viewing. Programs I remember vividly include Doctor Who [1963-89], Chorlton and the Wheelies [1976-79], Blake’s 7 [1978-81], and Battle of the Planets [1978-79]. These days I’m a flat-out, awe-struck fan of Buffy the Vampire Slayer [1997-2003].

We didn’t see many films when I was young, but since my teens I’ve been watching more. I’m very tolerant of sf bubblegum (though the truly moronic, like Independence Day [Emmerich 1996] or Burton’s Planet of the Apes [2001], leaves me frigid). I loved The Matrix [Wachowski brothers 1999] and I’m sure I’m not the only writer who can feel its influence, especially in fight scenes. I loved the Alien franchise, particularly Alien [Scott 1979] and Alien3 [Fincher 1992] (which I think is very under-rated). I like most half-decent (and many completely un-decent) monster films. I like John Carpenter when he’s on form—I’ve seen Prince of Darkness [1987] probably more than any other film. In terms of influences, the aesthetic that I try to filch respectfully comes most from filmmakers like the Quay Brothers and Jan Švankmajer.

Probably one of the most enduring influences on me was a childhood playing RPGs: Dungeons and Dragons [D&D] and others. I’ve not played for sixteen years and have absolutely no intention of starting again, but I still buy and read the manuals occasionally. There were two things about them that particularly influenced me. One was the mania for cataloguing the fantastic: if you play them for any length of time, you get to know pretty much all the mythological beasts of all pantheons out there, along with a fair bit of the theology. I still love all that—I collect fantastic bestiaries, and one of the main spurs to write a secondary-world fantasy was to invent a bunch of monsters, half of which I’m sure I’ll never be able to fit into any books.

The other, more nebulous, but very strong influence of RPGs was the weird fetish for systematization, the way everything is reduced to “game stats.” If you take something like Cthulhu in Lovecraft, for example, it is completely incomprehensible and beyond all human categorization. But in the game Call of Cthulhu, you see Cthulhu’s “strength,” “dexterity,” and so on, carefully expressed numerically. There’s something superheroically banalifying about that approach to the fantastic. On one level it misses the point entirely, but I must admit it appeals to me in its application of some weirdly misplaced rigor onto the fantastic: it’s a kind of exaggeratedly precise approach to secondary world creation.

I’m conscious of the problems with that: probably my favorite piece of fantastic-world creation ever is the VIRICONIUM series by M. John Harrison [The Pastel City (1971), A Storm of Wings (1980), In Viriconium (1982), and Viriconium Nights (1984; rev. 1985)], which is carefully constructed to avoid any domestication, and which thereby brilliantly achieves the kind of alienating atmosphere I’m constantly striving for, so it’s not as if I think that quantification is the “correct” way to construct a world. But it’s one that appeals to the anal kid in me. To that extent, though I wouldn’t compare myself to Harrison in terms of quality, I sometimes feel as if, formally, my stuff is a cross between Viriconium and D&D.

JG: You mentioned being drawn to the systematization in RPGs. How do you see that in your writing?

CM: I start with maps, histories, time lines, things like that. I spend a lot of time working on stuff that may or may not actually find its way into the novel, but I know a lot more about the world than makes it into the stories. That’s the “RPG” factor: it’s about systematizing the world.

But though that’s my method, I don’t start with it. I don’t start with a bunch of graph papers and rulers. When I’m writing a book, generally I start with the mood and setting, along with a couple of specific images—things that have come into my head, totally abstracted from any narrative, that I’ve fixated on. After that, I construct a world, or an area, into which that general setting, that atmosphere, and the specific images I’ve focused on can fit. It’s at that stage that the systematization begins for me.

I hope this doesn’t sound pompous, but that’s how I see the best weird fiction as the intersection of the traditions of Surrealism with those of pulp. I don’t start with the graph paper and the calculators like a particular kind of D&D dungeonmaster: I start with an image, as unreal and affecting as possible, just like the Surrealists. But then I systematize it, and move into a different kind of tradition.

I grew up with a love for the Surrealists which has never faded: in particular, the works of Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, Hans Bellmer, and Paul Delvaux, along with those adopted by or close to the Surrealists, like Edward Burra, James Ensor, and Frida Kahlo. Graphic artists like Piranesi, Dürer, Escher, Bellmer’s pen-and-ink work, Mervyn Peake, Tenniell, and so on, are influential. As to modern comics and graphic art, I admire David Sandlin, Charles Burns, Kim Dietsch, Julie Doucet, and Chris Ware; from the post-punk comics underground, Burne Hogarth; and more mainstream British children’s comic artists like Ken Reid. I draw myself, pen and ink stuff, often illustrating my own stories.

I was always into everything to do with sf, fantasy, horror (as well as things set under the sea, which, along with dinosaurs, is honorary fantasy). I grew up on children’s sf by people like Douglas Hill and Nicholas Fisk, as well as horror comics, which were, in retrospect, deeply odd and unpleasant. Michael de Larrabeiti’s BORRIBLES books [The Borribles (1976), The Borribles Go For Broke (1981), and Across the Dark Metropolis (1986)] were massively influential. When I was a kid I read pretty much any sf I could get my hands on, so there was a lot of good pulp along with the classics—people like Lloyd Biggle, Jr. and Linsday Gutteridge—and that reveling in genre influenced me a lot. I read a review of Perdido Street Station which said that for a Clarke winner it’s surprisingly unashamed of its roots, which I take as a massive compliment. Overall, though, what I liked best was the aesthetic of alienation, of the macabre and grotesque, so I preferred New Worlds-type stuff to American Golden Age: Aldiss, Harrison, Moorcock, Disch, Ballard, and the like are all heroes of mine.

I still find myself riffing off books from my past constantly, sometimes without remembering what I’m basing my writing on. New Crobuzon [the setting of Perdido Street Station] is highly influenced by Brian Aldiss’s The Malacia Tapestry [1976] and Tim Powers’s Anubis Gates [1983], but they’d permeated me so deeply I was initially less conscious of them than of other influences. The very first (never-ever-to-see-the-light-of-day) New Crobuzon story I wrote was about the invention of photography in a fantasy city—which is precisely the plot of Aldiss’s book. I’d forgotten that I was remembering it. I’m still scared of inadvertently ripping people off.

I always loved classic ghost stories, like Henry James’s and Robert Aikman’s. I liked Lovecraft, and then maybe eight years ago I started getting very interested in early weird fiction: Arthur Machen, Robert Chambers, E.H. Visiak, William Hope Hodgson, Clark Ashton Smith, David Lindsay (though he’s not in quite the same tradition, there are shared aesthetics). There were two things I found particularly compelling about this work. One was the peculiarities of pulp style. If you look at the way critics describe Lovecraft, for example, they often say he’s purple, overwritten, overblown, verbose, but it’s unputdownable. There’s something about that kind of hallucinatorily intense purple prose which completely breaches all rules of “good writing,” but is somehow utterly compulsive and affecting. That pulp aesthetic of language is something very tenuous, which all too easily simply becomes shit, but is fascinating where it works. Though I also love much more minimalist writers, it’s that lush approach that I’m drawn to in terms of my own writing, for good and bad.

The other thing I liked about weird fiction was its location at the intersection of sf, fantasy, and horror. Lovecraft’s monsters do magic, but they’re time-traveling aliens with über-science, who do horrific things. Hodgson’s are similar (though less scientifically savvy). David Lindsay’s “spaceship” travels back to Arcturus by totally spurious—and not even remotely convincing—science, but it masquerades as sf. I find that bleeding of genre edges completely compelling. There’s been a (to my mind rather scholastic and sterile) debate about whether Perdido Street Station is sf or fantasy (or even horror—it made the long-list for the Bram Stoker Award). I always say that what I write is weird fiction, in that it is self-consciously at the intersection.

Some writers loom in my consciousness for single works, some for their whole oeuvre. M. John Harrison I consider one of the greatest living writers in any genre, and his influence on me is immense. Mervyn Peake, for his combination of lush language and aesthetic austerity; Gene Wolfe, for oddly similar reasons; all of Iain Sinclair’s books, but particularly Downriver [1991]; Alasdair Gray, especially Lanark [1981]; Russell Hoban, especially Riddley Walker [1980]; a book called Junglist by people calling themselves “Two Fingers” and “James T. Kirk” [1997]. I find Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre [1847] continually astonishing.

I love short stories, and there are writers like Borges, Calvino, and Stefan Grabinski whose short work is a constant reference, but there are others who loom large for me on the strength of a single piece: Julio Cortazar’s “House Taken Over,” E.L. White’s “Lukundoo,” Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper,” Saki’s “Sredni Vastar.” I just finished Kelly Link’s collection Stranger Things Happen [2001], and can already feel her influencing me. Writers I’ve come to more recently include John Crowley, Unica Zürn (Hans Bellmer’s partner), Jeff VanderMeer, and Jeffrey Thomas.

The biggest recent influence on me, though, is not an sf writer: it’s the Zimbabwean Dambudzo Marechera, who died fourteen years ago. I first read him a decade ago, but came back to him recently and read all his published work. He’s quite astonishing. His influences are radically different from the folklorist tradition that one often associates with African literature. He writes in the tradition of the Beats, the Surrealists, the Symbolists, and he marshals their tools to talk about the freedom struggle, the iniquities of post-independence Zimbabwe, racism, loneliness, and so on. His poetry and prose are almost painfully intense and suffer from all the problems you’d imagine—the writing can be prolix and clunky—but the way he constantly wrestles with English (which wasn’t his first language) is extraordinary. He demands sustained effort from the reader, so that the work is almost interactive—reading it is an active process of collaboration with the writer—and the metaphors are simultaneously so unclichéd and so apt that he reinvigorates the language. The epigram to The Scar is taken from his most obscure book, Black Sunlight [1980], and he is a very strong presence throughout my recent writing.

JG: I want to turn the discussion from literary influences to your political involvement. Would you describe that involvement, discussing its effect on your writing?

CM: I was always left-wing, and from the age of about thirteen I’ve been involved in campaigns against nuclear weapons and apartheid, going on marches and demonstrations. Later, I became interested in postmodernist philosophy, but became very dissatisfied with it in my second year of university. I was studying anthropology, and I felt there was something theoretically disingenuous about postmodernism’s rejection of “grand narratives.” Specifically, its inability to deal with the cross-cultural nature of women’s oppression pissed me off, and for a brief while I turned to feminist theory. But I also felt there were serious lacunae in that tradition, and, while I continue to identify with feminism as a political struggle, I was unsatisfied by some of its theoretical blindspots.

At Cambridge there was an organization of Marxist students, and I’d been deeply impressed with the rigor and scope of their arguments, as well as their activism. Like most students, I knew that Marxism was teleological, outdated, and wrong, but I was stunned to find out that it wasn’t really any of those things, nor did it have the slightest connection with Stalinism. Two things in particular persuaded me of Marxism’s validity. One was that this theoretical approach dovetailed perfectly with my pre-existing political instincts and commitments, and gave them more rigor. The other was that Marxism— historical materialism—was theoretically all-encompassing: it allowed me to understand the world in its totality without being dogmatic. I’d felt, for example, that while feminist theory might have an explanation of gender inequality, it didn’t have much to offer on, say, international exchange rates. Marxism was able to make sense of all the various social phenomena from a unified perspective.

Although we revolutionary socialists are always accused of being utopian, nothing strikes me as more utopian than the reformist belief that with a bit of tinkering and some good faith, we can systematically improve the world. You have to ask how many decades of broken promises and failed schemes it will take to disprove that hope. Marxism isn’t about saying you’ll get a perfect world: it’s about saying we can get a better world than this one, and it’s hard to imagine, no matter how many mistakes we make, that it could be much worse than the mass starvation, war, oppression, and exploitation we have now. In a world where 30,000 to 40,000 children die of malnutrition daily while grain ships are designed to dump food into the sea if the price dips too low, it’s worth the risk.

For the last five years, I’ve been an activist with the International Socialist Tendency, and in a broader organization called the Socialist Alliance—as a member of which I stood for parliament in the recent general elections. I’m not an activist by predisposition but by conviction. Generally, I’d much rather be reading sf than being on a picket line, but I simply cannot believe that this world is the best we can do, and I can’t relax while it’s all we’ve got.

Socialism and sf are the two most fundamental influences in my life.

JG: Let’s turn to more specific discussion about your novels, and I’d like to begin by asking about your first novel, King Rat. Why did you choose drum’n’bass/jungle music as the musical score for the novel?

CM: I chose it because I love it. It’s rhythmically, thematically, aesthetically powerful. It’s a music constructed on theft, it’s a mongrel of a hundred snatches of stolen music. That’s what sampling is. And there are places in King Rat where I snatched a bunch of real lyrics, and looped them over each other, so the writing mimicked the music. It wasn’t entirely conscious, though—consciously, I was trying to mimic the rhythm of the music. Drum’n’bass is a music born out of the working-class—and unemployed—culture in London. Obviously it’s politically important to me not to pathologize, demonize, or fetishize working-class culture, but I didn’t choose to use it for political reasons so much as because it’s where the music’s at.

JG: The story of the Pied Piper of Hamlin is central to the novel, and the African trickster Anansi is there as well. Would you expand on your use of folk tales and myths in King Rat?

CM: All the animal superiors came from various mythic or artistic influences. The Anansi in the book is more the spider in his West Indian incarnation. The King of the Cats is mentioned, who’s a fairy tale figure (and also refers to An Arabian Nightmare by Robert Irwin [1983]). Kataris, Queen Bitch, is a demon in charge of dogs from a pantheon I can’t remember. Loplop, Bird Superior, is a character from Max Ernst’s paintings. Lord of the Flies refers to the novel of that name [by William Golding 1959], of course. All the animals in the novel have their own boss, and you’ve got figures from African, European, mythic, and artistic traditions all mixed up.

JG: The London Underground—what I’d call the subway system in the US—forms a series of metaphors for much of what goes on in the novel, from the use of subterranean settings, to its secret (underground) history of London, to the underground music scene. Would you discuss that?

CM: There’s a whole tradition of “underground London” books, of which Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere [1998] is probably the most well-known and successful. Partly it’s because it’s such an old city, and it’s been constructed on top of earlier layers. There are rivers that have been covered up by the city, and tunnels and construction, of which the tube (the subway trains) are a relatively recent but culturally weighty addition. Of course, the idea of things lurking around below the surface is such a potent image it’s no surprise that it features heavily in literature.

There’s something particularly powerful about the underground trains in London. They’re the oldest subway network in the world, and they are an absolutely central part of London culture. The tube map has become incredibly iconic. The very names of stations and train lines loom very large in our culture, so they were ripe to be pilfered. The details I wrote were right at the time—there’s a scene set in Mornington Crescent Station, which is particularly well-known in Britain because it features in a very popular radio comedy show [I’m Sorry I Haven’t A Clue]. Setting a violent and unpleasant scene there was kind of like pissing in a cozy bedroom.

JG: “Let’s put the ‘rat’ back into ‘Fraternity’” (317), Saul declaims at the end of King Rat. And you put fraternity into the novel. How and why is that an important theme in the novel?

CM: The “revolution” at the end of the novel is structured around the slogans of the French Revolution, not the Bolshevik revolution, which has been flagged through references to Lenin earlier in the novel. In other words, for those who’ve read a bit of Marxist theory, it is a bourgeois revolution, rather than a socialist one. It’s not a really happy ending, in that the rats, if they follow through on Saul’s suggestion, won’t usher in any kind of utopia, but will only get to where we humans are now.

JG: Turning to Perdido Street Station, how is it a London novel?

CM: In a very straightforward way, the city of New Crobuzon is clearly analogous to a chaos-fucked Victorian London. But it’s more than just the geography (river straddling, near the coast) and the industry (heavy, riddled with class conflict). It’s the way the city intersects with the literature that chronicles it. London is a trope for literature in an incredibly strong way: “Hell is a city much like London,” Shelley says, and through Blake and de Quincey, and Iain Sinclair, and Chesterton, and Machen, and Ackroyd, and Gaiman, and all the others, London is a neurotic tic for literature. Take those ideas—the danger, the intricacy, the mystery, the rich fecundity, the semi-autonomous architecture—and magic/surreal/acid it up a bit: that’s New Crobuzon. Though New Crobuzon contains other cities—Cairo in particular—it’s London at heart.

JG: John Clute talks about British sf being about ruins, expressing a pessimism about expansionism gone wrong (at the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts, March 2002). Can you speak to that in terms of Perdido Street Station?

CM: Post-New Worlds sf is partly pessimistic, but it’s more melancholic than miserable. It rather likes being in the ruins. I love that aesthetic, and it’s what I grew up on. I think, though, that Perdido Street Station is a little more muscular than that. It’s more pulpy, in what I hope are good as well as bad ways. Where the characters of New Worlds writers—who are my heroes—had “breakfast among the ruins,” the people in New Crobuzon busily build some other piece of shit using parts of the ruins. The ruins are still there, but I think that there’s more dynamism towards the environment. This is emphatically not a criticism of the earlier writers—it’s just an observation about a distinction of approach.

JG: Is Perdido Street Station in some way a child of Thatcherite, or Majorite, or Blairite England?

CM: I think you have to disaggregate them. Very crudely, I think that the New Worlds writers are writers of social collapse, of a political downturn, of the closing down of possibilities, and of worsening tensions without much of a sense of alternative, though I think their pessimism isn’t as straightforward as it may appear to be. I think that what’s happened recently is that we still have the same aggressive, neoliberal, profit-driven, and anti-human agenda at the top, but there’s been an amazingly exciting sense of alternatives (the protests against the World Trade Organization in Seattle in 2000 form a useful watershed) which was missing in the 1980s, and even through the 1990s. In the cultural milieu, that doesn’t translate into obviously political or “optimistic” sf, but it does inform it with what is perhaps a more powerful sense of social agency and interaction with both real and fictional landscapes. I don’t think my writing’s terribly optimistic, though I am.

JG: In what ways does the novel reflect or respond to the contemporary situation politically, aesthetically, personally, or otherwise?

CM: There are certain deliberate references: the dock strike by Vodyanoi dockers is a direct reference to the long-running labor dispute in Liverpool. There are general points about the depiction of social tensions and so on. But I don’t write fiction to comment on the day-to-day situation, so I think the bulk of the response or reflection is in that generalized way I spoke of in the last answer. I think it’s to do with coming to terms with a new sense of social agency.

JG: In what ways does the novel develop or explore Marxism? How does it bring Marxism into a contemporary perspective? Is there a kind of postmodern Marxism and, if so, is it at work in Perdido Street Station?

CM: I don’t really accept the term “postmodern” as explaining very much in the real world—I’d use it as a description for certain schools of theory, and certain schools of art. I don’t consider myself a postmodernist in any real sense. Postmodernism has done quite a good job of colonizing lots of techniques and implying that anything like those techniques is therefore “postmodernist.” You can use certain deconstructive techniques, for example, without being a postmodernist—still being a classical Marxist. I realize that to some extent this is a semantic quibble, and if someone finds it useful to describe my stuff in that way, that’s up to them, but I’d resist it, because I don’t think it’s fair that hybridity, uncertainty, blurring identities, fracturing, formal experimentation, or the blurring of high and low culture should be ceded to postmodernism! I want all that, and I’m a classical Marxist. For me, much of that list is about dialectics, which is something that underpins a lot of what I think about. The novel isn’t “about” Marxism. When I want to explore Marxism, I write non-fiction. However, I represent certain concerns in fictional form because they fascinate me. There are direct political topics, such as the arguments over union organization, over the class basis of fascism, over the internal contradictions of racist consciousness, and so on, in the book. There are also slightly more abstruse ones. The model of consciousness explored in the book—where human consciousness is apparently ego plus subconscious, but is in fact the dialectical interrelation of the two, rather than an arithmetic addition, is a playful exploration not only of dialectics. It also explores the models of consciousness that I think explain social agency and the relationship between intuition and knowledge, which is something that Gramsci, for example, talks about a great deal.

I write the novel because I love writing books about weird shit and monsters, but I fill it with the concerns and fascinations that are in my head, and it’s no surprise that Marxism features large in there.

JG: You resist the “postmodern” label that people like myself are so eager to use. Would you expand on your statement that “much of that list is about dialectics which is something that underpins a lot of what I think about”?