#even better if it used a resolution mechanic other than dice

Text

Hey TTRPG Nerds

I’m back on my bullshit again. What are some indie games with unique systems that aren’t D&D, PBTA/FitD, or Fate-based?

How do they use unique mechanics to accomplish cool stuff?

Story games, OSR, you name it — all welcome!

#also like obviously excluding stuff like savage worlds and world of darkness#no Big Game Companies#I wanna see your weird and wonderful#even better if it used a resolution mechanic other than dice#looking at you dread my beloved#ttrpgs#tabletop#ttrpg#indie games#role playing games

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Far Roofs: Systems

Hi!

Today I’m going to talk a little bit more about my forthcoming RPG, the Far Roofs. More specifically, I want to give a general overview of its game mechanics!

So the idea that first started the Far Roofs on the road to being its own game came out of me thinking a lot about what large projects feel like.

I was in one of those moods where I felt like the important thing in an RPG system was the parallel between that system and real-world experience. Where I felt like the key to art was always thinking about the end goal, or at least a local goal, as one did the work; and, the key to design was symmetry between the goals and methods, the means and ends.

I don't always feel that way, but it's how I work when I'm feeling both ambitious and technical.

So what I wanted to do was come up with an RPG mechanic that was really like the thing it was simulating:

Finding answers. Solving problems. Doing big things.

And it struck me that what that felt like, really, was a bit like ...

You get pieces over time. You wiggle them around. You try to fit them together. Sometimes, they fit together into larger pieces and then eventually a whole. Sometimes you just collect them and wiggle them around until suddenly there's an insight, an oh!, and you now know everything works.

The ideal thing to do here would probably be having a bag of widgets that can fit together in different ways---not as universally as Legos or whatever, but, like, gears and connectors and springs and motors and whatever. If I were going to be building a computer game I would probably think along those lines, anyway. You'd go to your screen of bits and bobs and move them around with your mouse until it hooked together into something that you liked.

... that's not really feasible for a tabletop RPG, though, at least, not with my typical financial resources. I could probably swing making that kind of thing, finding a 3d printing or woodworking partner or something to make the pieces, for the final kickstarter, but I don't have the resources to make a bunch of different physical object sets over time while I'm playtesting.

So the way I decided that I could implement this was by drawing letter tiles.

That I could do a system where you'd draw letter tiles ... not constantly, not specifically when you were working, but over time; in the moments, most of all, that could give you insight or progress.

Then, at some point, you'd have enough of them.

You'd see a word.

That word'd be your answer.

... not necessarily the word itself, but, like, what the word means to you and what the answer means to you, those would be the same.

The word would be a symbol for the answer that you've found, as a player and a character.

(The leftover letters would then stick around in your hand, bits of thought and experience that didn't directly lead to a solution there, but might help with something else later on.)

Anyway, I figured that this basic idea was feasible because, like, lots of people own Scrabble sets. Even if you don't, they're easier to find than sets of dice!

For a short indie game focused on just that this would probably have been enough of a mechanic all on its own. For a large release, though, the game needed more.

After thinking about it I decided that what it wanted was two more core resolution systems:

One, for stuff like, say ... kickstarter results ... where you're more interested in "how well did this do?" or "how good of an answer is this?" than in whether those results better fit AXLOTL or TEXTUAL. For this, I added cards, which you draw like letter tiles and combine into poker hands. A face card is probably enough for a baseline success, a pair of Kings would make the results rather exciting, and a royal flush result would smash records.

The other core system was for like ... everyday stuff. For starting a campfire or jumping a gap. That, by established RPG tradition, would use dice.

...

I guess technically it didn't have to; I mean, like, most of my games have been diceless, and in fact we've gotten to a point in the hobby where that's just "sort of unusual" instead of actually rare.

But, like, I like dice. I do. If I don't use them often, it's because I don't like the empty page of where to start in the first place building a bespoke diced system when I have so many good diceless systems right there.

... this time, though, I decided to just go for it.

--

The Dice System

So a long, long time ago I was working on a game called the Weapons of the Gods RPG. Eos Press had brought me in to do the setting, and somewhere in the middle of that endeavor, the game lost its system.

I only ever heard Eos' side of this, and these days I tend to take Eos' claims with a grain of salt ... but, my best guess is that all this stuff did happen, just, with a little more context that I don't and might not ever know?

Anyway, as best as I remember, the first writer they had doing their system quit midway through development. So they brought in a newer team to do the system, and halfway through that the team decided they'd have more fun using the system for their own game, and instead wrote up a quick alternate system for Weapons of the Gods to use.

This would have been fine if the alternate system were any good, but it was ... pretty obviously a quick kludge. It was ...

I think the best word for it would be "bad."

I don't even like the system they took away to be their own game, but at least I could believe that it was constructed with love. It was janky but like in a heartfelt way.

The replacement system was more the kind of thing where if you stepped in it you'd need a new pair of shoes.

It upset me.

It upset me, and so, full wroth, I decided to write a system to use for the game.

Now, I'd never done a diced system before at that point. My only solo game had been Nobilis. So I took a bunch of dice and started rolling them, to see ... like ... what the most fun way of reading them was.

Where I landed, ultimately, was looking for matches.

The core system for Weapons of the Gods was basically, roll some number of d10s, and if you got 3 4s, that was a 34. If you got 2 9s, that was a 29. If your best die was a 7 and you had no pairs at all, you got 1 7. 17.

It didn't have any really amazing statistical properties, but the act of rolling was fun. It was rhythmic, you know, you'd see 3 4s and putting them together into 34 was a tiny tiny dopamine shot at the cost of basically zero brain effort. It was pattern recognition, which the brain tends to enjoy.

I mean, obviously, it would pall in a few minutes if you just sat there rolling the dice for no reason ... but, as far as dice rolling goes, it was fun.

So when I went to do an optional diced system for the Chuubo's Marvelous Wish-Granting Engine RPG, years later, to post here on tumblr ... I already knew what would make that roll fun. That is, rolling a handful of dice and looking for matches.

What about making it even more fun?

... well, critical results are fun, so what about adding them and aiming to have a lot of them, though still like rare enough to surprise?

It made sense to me to call no matches at all a critical failure, and a triple a critical success. So I started fiddling with dice pool size to get the numbers where I wanted them.

I'm reconstructing a bit at this point, but I imagine that I hit 6d10 and was like: "these are roughly the right odds, but this is one too many dice to look at quickly on the table, and I don't like that critical failure would be a bit more common than crit success."

So after some wrestling with things I wound up with a dice pool of 5d6, which is the dice pool I'm still using today.

If you roll 5d6, you'll probably get a pair. But now and then, you'll get a triple (or more!) My combinatorics is rusty, so I might have missed a case, but, like ... 17% of the time, triples, quadruples, or quintuples? And around 9% chance, for no matches at all?

I think I was probably looking for 15% and 10%, that those were likely my optimum, but ... well, 5d6 comes pretty close. Roughly 25% total was about as far as I thought I could push critical results while still having them feel kind or rare. Like ...

If I'm rolling a d20 in a D&D-like system, and if I'm going to succeed on an 18+, that's around when success is exciting, right? Maybe 17+, though that's pushing it? So we want to fall in the 15-20% range for a "special good roll." And people have been playing for a very long time now with the 5% chance of a "1" as a "special bad roll," and that seemed fine, so, like, 20-25% chance total is good.

And like ...

People talk a lot about Rolemaster crit fail tables in my vicinity, and complain about the whiff fests you see in some games where you keep rolling and rolling and nothing good or bad actually happens, and so I was naturally drawn to pushing crit failure odds a bit higher than you see in a d20-type game.

Now, one way people in indie circles tend to address "whiff fests" is by rethinking the whole dice-rolling ... paradigm ... so you never whiff; setting things up, in short, so that every roll means something, and every success and failure mean something too.

It's a leaner, richer way of doing things than you see in, say, D&D.

... I just didn't feel like it, here, because the whole point of things was to make dice rolling fun. I wanted people coming out of traditional games to be able to just pick up the dice and say "I'm rolling for this!" because the roll would be fun. Because consulting the dice oracle here, would be fun.

So in the end, that was the heart of it:

A 5d6 roll, focusing on the ease of counting matches and the high but not exorbitant frequency of special results.

But at the same time ...

I'm indie enough that I do really like rolls where, you know, every outcome is meaningful. Where you roll, and there's never a "whiff," just a set of possible meaningful outcomes.

A lot of the time, where I'm leaning into "rolls are fun, go ahead and roll," what it means to succeed, to fail, to crit, all that's up to the group, and sometimes it'll be unsatisfying. Other times, you'll crit succeed or crit fail and the GM will give you basically the exact same result as you'd have gotten on a regular success or failure, just, you know, jazzing up the description a bit with more narrative weight.

But I did manage to pull out about a third of the rolls you'll wind up actually making and assign strong mechanical and narrative weight to each outcome. Where what you were doing was well enough defined in the system that I could add some real meat to those crits, and even regular success and regular failure.

... though that's a story, I think, to be told some other time. ^_^

230 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's OSR? I've seen you mention it several times in your RPG posts. Is it like a genre of rpg or...?

Hey, sorry I took so long to reply to this lol you probably already just googled it by now.

But like. Anyway.

OSR (Old-School Revival, Old-School Renaissance, and more uncommonly Old-School Rules or Old-School Revolution, no one can really agree on what the R means) is less like a genre and more like a movement or a loosely connected community that seeks to capture the tone, feel and/or playstyle of 70's and 80's fantasy roleplaying games (with a particular emphasis on old-school editions of Dungeons and Dragons, particularly the Basic D&D line but pretty much anything before 3e falls under this umbrella), or at least an idealized version of what people remember those games felt like to play.

There isn't exactly a consensus on what makes a game OSR but here's my personal list of things that I find to be common motifs in OSR game design and GM philosophy. Not every game in the movement features all of these things, but must certainly feature a few of them.

Rulings over rules: most OSR games lack mechanically codified rules for a lot of the actions that in modern D&D (and games influenced by it) would be covered by a skill system. Rather that try to have rules applicable for every situation, these games often have somewhat barebones rules, with the expectation that when a player tries to do something not covered by them the GM will have to make a ruling about it or negotiate a dice roll that feels fair (a common resolution system for this type of situation is d20 roll-under vs a stat that feels relevant, a d6 roll with x-in-6 chance to succeed, or just adjudicating the outcome based on how the player describes their actions)

"The solution is not on your character sheet": Related to the point above, the lack of character skills means that very few problems can be solved by saying "I roll [skill]". E.g. Looking for traps in an OSR game will look less like "I rolled 18 on my perception check" and more like "I poke the flagstones ahead with a stick to check if they're pressure plates" with maybe the GM asking for a roll or a saving throw if you do end up triggering a trap.

High lethality: Characters are squishy, and generally die much more easily. But conversely, character creation is often very quick, so if your character dies you can usually be playing again in minutes as long as there's a decent chance to integrate your new PC into the game.

Lack of emphasis on encounter balance: It's not uncommon for the PCs to find themselves way out of their depth, with encounters where they're almost guaranteed to lose unless they run away or find a creative way to stack the deck in their favor.

Combat as a failure state: Due to the two points above, not every encounter is meant to be fought, as doing so is generally not worth the risk and likely to end up badly. Players a generally better off finding ways to circumvent encounters through sneaking around them, outsmarting them, or out-maneauvering them, fighting only when there's no other option or when they've taken steps to make sure the battle is fought on their terms (e.g. luring enemies into traps or environmental hazards, stuff like that)

Emphasis on inventory and items: As skills, class features and character builds are less significant than in modern D&D (or sometimes outright nonexistent), a large part of the way the players engage with the world instead revolves around what they carry and how they use it. A lot of these games have you randomly roll your starting inventory, and often this will become as much a significant part of your character as your class is, even with seemingly useless clutter items. E.g. a hand mirror can become an invaluable tool for peeping around corners and doorways. This kind of gameplay techncially possible on modern D&D but in OSR games it's often vital.

Gold for XP: somewhat related to the above, in many of these games your XP will be determined by how much treasure you gather, casting players in the role and mindset of trasure hutners, grave robbers, etc.

Situations, not plots: This is more of a GM culture thing than an intrinsic feature of the games, but OSR campaigns will often eschew the long-form GM-authored Epic narrative that has become the norm since the late AD&D 2e era, in favor of a more sandbox-y "here's an initial situation, it's up to you what you do with it" style. This means that you probably won't be getting elaborate scenes plotted out sessions in advance to tie into your backstory and character arc, but it also means increased player agency, casting the GM in the role of less of a plot writer or narrator and more of a referee.

Like I said, these are not universal, and a lot of games that fall under the OSR umbrella will eschew some or most of these (it's very common for a lot of games to drop the gold-for-xp thing in favor of a different reawrd structure), but IMO they're a good baseline for understanding common features of the movement as a whole.

Of course, the OSR movement covers A LOT of different games, which I'd classify in the following categories by how much they deviate from their source of inspiration:

Retroclones are basically recreations of the ruleset of older D&D editions but without the D&D trademark, sometimes with a new coat of paint. E.g. OSRIC and For Gold and Glory are clones of AD&D (1e and 2e respectively); Whitebox and Fantastic Medieval Campaigns are recreations of the original 1974 white box D&D release; Old School Essentials, Basic Fantasy and Labyrinth Lord are clones of the 1981 B/X D&D set. Some of these recreate the original rules as-is, editing the text or reorganizing the information to be clearer but otherwise leaving the meachnics unchanged, while others will make slight rules changes to remove quirks that have come to be considered annoying in hindsight, some of them might mix and match features from different editions, but otherwise they're mostly straight up recreations of old-school D&D releases.

There are games that I would call "old-school compatible", that feature significant enough mechanical changes from old-school D&D to be considered a different game, but try to maintain mechanical compatibility with materials made for it. Games like The Black Hack, Knave, Macchiato Monsters, Dungeon Reavers, Whitehack, etc. play very differently from old-school D&D, and from each other, but you generally can grab any module made for any pre-3e D&D edition and run it with any of them with very little to no effort needed in conversion.

There's a third category that I wouldn't know how to call. Some people call then Nu-OSR or NSR (short for New School revolution) while a small minority of people argue that they aren't really part of the OSR movement but instead their own thing. I've personally taken to calling them "Old School Baroque". These are games that try to replicate different aspects of the tone and feel of old-school fantasy roleplaying games while borrowing few to none mechanics from them and not making any particular attempts to be mechanically compatible. Games like Into the Odd, Mörk Borg, Troika!, a dungeon game, FLEE, DURF, Songbirds, Mausritter, bastards, Cairn, Sledgehammer, and too many more to name. In my opinion this subsection of the OSR space is where it gets interesting, as there's so many different ways people try to recreate that old-school flavor with different mechanics.

(Of course, not everything fits neatly into these, e.g. I would consider stuff like Dungeon Crawl Classics to be somewhere inbetween category 1 and 2, and stuff like GloG or RELIC to be somewhere imbetween categories 2 and 3)

The OSR movement does have its ugly side, as it's to be expected by the fact that a huge part of the driving force behind it is nostalgia. Some people might be in it because it harkens back to a spirit of DIY and player agency that has been lost in traditional fantasy roleplaying games, but it's udneniable that some people are also in it because for them it harkens back to a time before "D&D went woke" when tabletop roleplaying was considered a hobby primarily for and by white men. That being said... generally those types of guys keep to themselves in their own little circlejerk, and it's pretty easy to find OSR spaces that are progressive and have a sinificant number of queer, POC, and marginalized creators.

223 notes

·

View notes

Text

RAR Musings #11: Rebuilding A System

I engaged in a reddit thread discussing "killing your darlings" lately, where they wanted their game to be "simple and approachable", "narratively driven", and "introduce elements of mech games that enthusiasts enjoy, but to people who aren't enthusiasts."

"Killing Your Darlings" has blown up as a game design buzzphrase people use to appear more experienced and wise than they actually are. Often, it's a bid to appear better read, or "oh woe is me, who must relinquish my idea to the void. Good thing I'm above all that, professional designer that I am, that I can sacrifice my preferences and ideals for the greater good," but for a single tear rolling down the cheek, but in this case, it was a genuine argument about whether something would contribute to the final product well or not.

I don't personally define a game with equipment heat, energy costs, and random lookup tables for an assortment of weapons in a catalogue to be "simple and approachable" for non-mech enthusiasts, nor particularly necessary for a "narratively driven" game, but I'm more upset about "narrative game" getting slapped on a lot of different products that don't actually have mechanics for driving a narrative. The 'stress' mechanic that they were dropping would actually give definition to the characters of the game, if the game's narrative was about said characters, but by removing it in favor of player agency, it's just... it's just a game. Not a story.

I fought about it, and offered some alternatives. Rather than a negative mechanic that removes player agency, why not a Brave mechanic, granting extra rewards for engaging in risk? Why have all these different mech parts, why not just have Parts, if non-mech enthusiasts weren't going to care? Why not come up with mechanics that actually DO tell a narrative, rather than just relying on DND-make believe?

The more I thought about it, the more mad I got, not just at the designer, but at myself, and Road and Ruin.

I don't like the phrase, Killing Your Darlings, to begin with. It implies that your idea is so specific, so inherent to the engine you're designing for, that there's absolutely no salvaging it. A new species, that winks in and out of existence, a twinkle, before you snuff it out, never to be seen again. Why not figure out a way for it to be used! Or if it doesn't fit or overworks the product, shelve it! Use it on a different project! Don't let your dreams be memes! You're a designer, not a farmer with a lame horse!

But I had invested so much time, so much design work, and been so pleased with the elegance of Road and Ruin's core resolution mechanic, that after coming to terms with the fact that it was bulky, time-consuming, involved adding too many numbers, and ultimately wasn't actually very fun, I resisted any notion of changing it. Even later, when I DID change proficiency from affecting the minimum dice value of the d10s, into being a flat value added to the d10s, the system still involved adding anywhere from 2-5 random values between 1 and 10, and then the proficiency value besides.

So why was I so willing to tear into this objectively decent mech game, and do so much design work trying to come up with ways to simplify it, when I wasn't willing to entertain simplifying Road and Ruin for a more enjoyable experience and a wider audience?

_______________________

I woke up the other day with a sudden idea.

Road and Ruin's core skill resolution system might involve too much math hinging on too many variables, but what about the combat system?

It was another system I'd done some major work on over time, but unlike skill checks, only really involved one dice roll, and no math after. I started to think how I might actually make the combat system the core skill check system, thus unifying the game under one mechanic, and being a lot faster, and more fun besides.

The gist of it is, that when making an attack in combat, you'd roll a d4 (Piercing/Accurate), d8 (Slash/Scrape, edged contact), or d12 (Bashing/Touch, only contact is necessary), subtracting the target's armor, and +/- an amount based on who had the edge in weapon skill. A 1 or less is a miss, and above half is full damage, based on a flat value determined by the weapon's weight, minus any lacking Strength needed to swing it. Anything in between is a Glancing Blow for half damage. There's also the Special system as well, but I'll leave that for another post; the point was, I wanted combat to come away having inflicted SOME damage each attack, rather than none, but for there to be a real fear of both heavily armored units, as well as expert swordsmen.

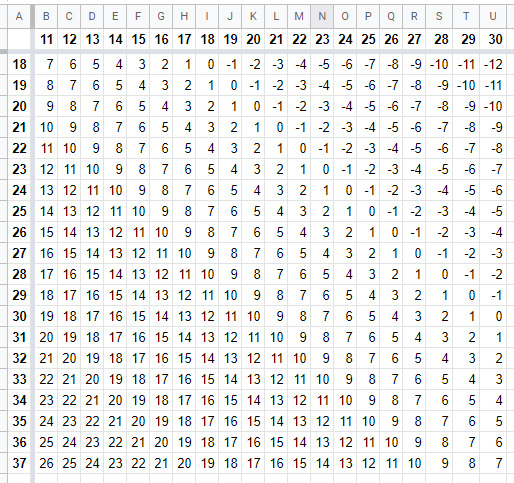

But what if that was how skill checks worked? Currently, the system assumes an average 2d10, up to 5d10, adding (proficiency/10 x specialization/5), and looks for multiples of 10; that is, 10+ is 1 success, 20+ is 2 successes, 30+ is 3, with successes being measures of what a creature can easily, with training, and with specialization do, relative to a creature of it's size and shape. An adult human can toss paper into a can with a 1; a wolf might be able to open a latched door with a 2-3, or 25. Blessings/Curses and gear could modify this in multiple ways, such as preventing rolls below or above a certain threshold, or allowing the reroll of one or more die.

If skill checks were instead a sliding scale, using a single d10, difficulty could be calculated before the roll was even made, like the impact of 2 points of armor on an attack roll. By sliding the scale of success, even physically using a sliderule, results of (1 Fail/And, 234 Fail, 5 Fail/But, 6 Succeed/But, 789 Success, and 10 Success/And) are moved left and right, and the die is left with the final say. Specializations can reduce the threshold of Succeed/And, while greater consequences for failure move up the threshold of Fail/And.

If 10% increments are too much, (especially for disciplines where the likelyhood of crafting a masterwork item should be less than 10%), a d100 still offers a "one dice" solution, but on 1% increments. In that case, the threshold for masterwork can be "specialization x proficiencies", and anyone with even one specialization can make repeat attempts, so long as they have the time and resources, to continue chiseling away until they've finished their magnum opus, gaining +1% chance of masterwork each roll, whereas a legendary master completes such works on a 50% basis.

In terms of gear, supportive equipment can either reduce the Success/And threshold, the regular success threshold, or allow for a reroll 'save' when rolling a failure, such as in the case of climbing rope stopping a fall. But, in each case that the support is used, it suffers a level of damage, and the Fail/And threshold of the follow-up save increases. Past a certain point, using intact, but damaged rope ends up being more risky than it's worth, without it explicitly preventing use.

In the case of blessings and curses, they can allow rerolls, or just flat +1/-1 effects. What I'm really warming up to with this idea is how just about everything boils down to using the single die, but in a way that's still got a lot of tools to play with.

________________

Now some cons. I'd done a LOT of work on the earlier system, and designed lots of spells, such as the Revision magic, Lethologica, a spell that allows the reroll of any one die in proximity, both supportively or debilitatingly. This was a lot more balanced when you were rolling 2-5 dice per throw, but a single die? Massively overpowered. I'd rather not upgrade the cost of what was essentially a cantrip to a fifth-level spell, so I'm going to have to figure out how I'd get to keep it and make it work still. One solution might be forcing the use of the d100, and having Lethologica alter the result by a number of points in either direction, being used to help sway results, but not effortlessly overturn them. It allows for spell scaling, with more mana converting to a greater degree of sway, and still allows sway in either direction, helping to save near-failures and fail near-saves.

Another issue is the case of Monstrous/Mini. When I changed RAR from being a 10-scale attribute system to a 5-scale, I was bothered by how I'd account for three-story giants, pixies, and small-world scenarios. I'd developed Monstrous and Mini, x5 and /5 multipliers for stats that helped to massively scale up or down the effects of 1-5 of any given attribute. So, a creature with Monstrous Strength 3 would multiply the results of their 3d10 roll by 2. Monstrous 2 Strength 4 would get (4d10 x 3). Boss monsters could still get trash rolls (2+3+1 x 2 is just 12, doable on 2d10) but still get high effects on average. Miniscule, on the other hand, reduces the character's Size by a stage, having them struggle to pick up thimbles and defend against ants. This complete overhaul of the core skill check resolution system doesn't have "10 = 1 success" anymore, so multiplying the results doesn't really work; not that it did, because it was slow, and unfun.

A solution for this is... a lookup table. Kind of. The actual value of each of the stats, 1-5, are actually still quite valid for establishing standards. If a creature has reasonable stats to do what they're looking to do, they should roll, no problem. If their stat is lacking, they suffer a -1 for every stage they're missing, and if they exceed, +1 for every stage they're over. But for Monstrous/Mini, like... maybe it's +/- 5 in each direction? And if Fail would get pushed off the board, it stays at 1, causing a chance for failure of 10%? I mean, engaging in a mental mindclash with an illithid SHOULD be next to impossible with their Monstrous Intelligence, but just the chance that they roll a 1 is probably more fun than "you literally just can't do it".

The question here is, if players who are generating their own creatures have a solid understanding of what Monstrous/Miniscule creatures are actually DO, without getting to experience them in action first. And, since the game actually IS narrative in nature, I don't see an issue with placing impossible monsters in front of players that they're not actually supposed to defeat, really. But it feels weird to not be multiplying the outcome of dice anymore.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Backstory, Acknowledgements, etc.

Before I dig into things for the game itself, some acknowledging my biggest inspiration, and a little storytelling.

The reason Magic Assholes in Space exists at all is because of a TTRPG called Space Kings, and the Pretend Friends podcast, run by Kevin Cole, creator of Space Kings and many other very cool games and maker of many cool podcasts! Space Kings is notable for it's card-based core resolution mechanic, and it's improvisational storytelling. Very influential, to say the least.

Back in 2018, my weekly game nights were a kind of in shambles. Scheduling problems and general burnout had killed several attempts at getting a consistent campaign going. We were both just too tired and switching systems, spending the time reinvesting in a new setting, only for the game to fall apart after a couple sessions was getting badly demoralizing.

So I had this stupid idea that combined my desire to play something with a tone like Space Kings, my ever-present itch to design a TTRPG, and a handful of ideas I'd piled up. Back in 2018, Space Kings wasn't out yet, (it is now! Go check it out!) but I still wanted to use that inspiration and I wanted to turn the act of designing the game into a group activity. Trying to dump a whole-ass setting on the table before the game started was a thing I'd also burned out on and not something I wanted to waste the energy on, so I adopted a more improv and collaborative approach for that, also.

I initially played with the idea of mixing and matching sets of dice, but the allure of Space King's "Faces and Aces" card mechanic just sounded too fun and I started getting this little voice in the back of my head that kept saying, "Why the hell not?" The whole idea might not even last or go for more than a single session, so I thought it was better to just take this chance and try it! At least it would be a chance to scratch that itch.

Why the hell not? would later become a sort of mantra for this whole thing.

I knew I wanted to do something with space as the setting, but with magic as a prominent element. The title "Magic Assholes in Space" came to me almost instantly and I don't think I could ever come up with something better and I really wouldn't want to either. It perfectly captures everything I wanted this game to be. After 2 weeks of lazily jotting down ideas and slapping together a character sheet in google docs, we jumped into our first playtest session and hit the ground running.

The first playtest session had a couple hiccups, but it worked! Some things needed tweaking, but that was fine! The players escaped the belly of a space dragon, fought a cosmic snail knight, assembled a new ship out of two ships, and installed a mythical V8 engine into it so they could escape the dark space between galaxies! It was awesome!

We had several players come and go, but the playtest turned into a year-long campaign that ended up being supremely memorable. Hands down the best experience I've ever had running any TTRPG in my life. Even with there being no rulebook and some big changes being made week to week, running and playing was a breeze in a way that none of my previous campaigns had ever been.

Now, in the intro post, I said I started in 2019 (since edited), and that made no sense for a particular reason. MAiS was actually started in 2018. My memory is just awful. This is mostly important because the first playtest that ran for over a year was put on pause in February 2020, which ended up being about a month before covid lockdowns started. For obvious reasons, things kinda went on indefinite pause. We had talked about returning to our storyline with the same characters and seeing where the story went after the crew decided that they'd fucked up too much in one galaxy and it was about time to go check out another one, but the opportunity just never really came around again.

Since then, development has slowed, but some big strides were made. We did a couple one-shots run by other players. There were the GenCon games in 2021, the short-lived Hypermall game in 2022, and the currently paused online game in 2023. There's talk of starting something new, but we're still in the very, very early pre-game phases on that.

I kept telling myself I'd keep working on it, but my desire to work on the game is seemingly proportional to the amount of time I spend running it. So, one of the things I hoped to accomplish by tumblr'ing stuff about MAiS is that it would both motivate me to do more work, give me excuses to talk with people about it, and allow me to trick my brain into staying in gamedev mode long enough to finish some kind of, at minimum, zine-like share-able version of the ruleset.

And here we are now! Space Kings is out and I can say that my game definitely shares its DNA, but also that it is distinctly divergent in its design philosophy. I hope this post gets some people to check it out, but I also hope people stick around to see what I've got going on with MAiS because I personally believe it's got a lot of cool things going for it.

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

So I played the OG game recently, and I decided to try and compliment every single person Cloud could possibly date (Tifa, Aerith, Yuffie and Barret), because I wanted to test if, somehow, Cloud would end up on the Gold Saucer date with someone else but still get the intimate version with Tifa under the Highwind. Sure enough, Aerith ended up being Cloud's date at Gold Saucer (since she starts off with the highest affection points) but I still got the high affection version of Cloud x Tifa under the Highwind.

It was so confusing. I thought "nah if I got the high affection version with Tifa under the Highwind, then I should've gotten Tifa as the Gold Saucer date earlier."

I think Remake and Rebirth did the affection mechanics better. Because there, I also tested if, somehow, you could compliment, or do sidequests with, every single person Cloud could possibly date, and I still ended up having Tifa's Resolution in Remake and Tifa as my date in Rebirth — and yes, I got the high affection version of the date where they finally kissed (since, even if you do get Tifa as your date, if your affinity is somehow still not high enough, they still hug but they don't kiss).

What do you think about the date/affection mechanics between the OG game and Remake/Rebirth?

Nomura already said back in 97 that Tifa's the story path, so her GS date is the main and the others are for replay value.

Tbh the way the pts tally is hard to track. I did a playthrough of OG aiming at getting equal pts for Tifa and Aerith, because it's literally impossible to get everyone at equal values because of how each option affects outcomes, but those two it's doable. I got Tifa's date, but tbph the math was annoying and having to check the date mechanics and pick answers according to how it added up made for some awkward AF scenes that felt so ooc.

Remake's resolutions are based on the ch3 and 8 sidequests. There's 6 in each chapter and if you do them all both Tifa and the other one have a total of 12 PTS by the sewer where you get 1 pt for whoever you choose as a tie breaker. If you have less than 5 PTS by that point then you get Barret's resolution.

It's easy to follow and execute for the dressed to the nines trophy because you gotta do 0-2, 3-5 or 6 sidequests to get Aerith's different dresses at wall market, where with Tifa you just do all 6 and make a different choice during alone at last.

Rebirth is anxiety inducing, almost like they wanted you to feel how Cloud feels that moment before you open the door to see who's waiting for you, so all you get first playthrough is the colour wheel that you can barely see because it's frigging tiny. You have to hope and pray you get the person Cloud likes and either laugh it off or pull a face and restart when you don't. Every choice is a dice roll of wondering did you pick the right thing to say. I guess like RL when you're with the person you like and hoping you don't sound like a moron every time you talk. It did make that first playthrough a lot less fun because you had to not do sidequests or certain things to make sure the person you wanted on the date would be the person on the date. Once the system unlocked and let us choose whoever it became more fun, but I don't like how the sidequests are tied to the date pts. Tbh because of all the ltd bs it made it unenjoyable and by the time you get the date you're on the backend of the game and there's no time to relax and enjoy anything else in it because you're heading to the temple and then the worst 23m of everybody's life with that cringe af nightmare date that was the biggest mistake they added to the game.

Tldr: thanks I (mostly) hate it.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

High 20 Sage X3 Manufacturing Marketing Consultant Jobs, Now Hiring

It is a significant defect which is inflicting misrepresentation of operating costs of the entire firm by tens of hundreds of PLN every month. Our Chief Accountant is unable to calculate appropriate financial result of year 2015. Moreover, any annual stocktaking is ineffective because software program keeps importing goods at totally different prices than entry costs. Furthermore, sales staff is unable to calculate their margin and fee on sales.

Unlike many other wage tools that require a critical mass of reported salaries for a given mixture of job title, location and experience, the Dice model could make accurate predictions on even unusual combos of job factors. The mannequin does this by recognizing patterns within the more than 600,000 salary information factors to infer how much every factor - job title, location, experience, education, and expertise - will influence the wage. The software sage x3 manufacturing is a bit overwhelming with many options that do not pertain to our business and discovering tasks is a bit cumbersome and time-consuming, though given extra time utilizing the software may improve this issue. We did should customise quite a bit that we didn't initially assume we must, and much of what was custom-made can't be modified by common customers . Overall, the system is extra user-friendly as far as information entry is compared to Sage 500.

Unless you might have deep pockets and may wait a number of years to “go live”, you’ll appreciate that Sage X3 is easy to implement, easy to use, and customizable whenever you need it. Price quotes are offered to enterprises within the USA and Canada only. Native compatibility with necessities from regulatory our bodies, so that data is mechanically gathered and offered in the best way, can cut back administrative overheads and assist your group meet its obligations extra successfully. Find out why traceability is essential for a successful supply chain. Quickly navigate the maze of global laws and restrictions in order to simplify compliance across currencies, areas, and rules.

This wildly-popular ERP system manages Sales, Finance, Inventory, Purchasing, CRM, and Manufacturing in a single built-in ERP software program solution. Sage X3's value is dependent upon a quantity of business and service necessities; evaluation the Sage X3 Pricing Guide to be taught more. Allows the consumer to offer quick information about the products, inventory, quotations, management of contacts, and deep-dive details about each SKU. You can create reports and change tariffs, discounts, distributors, carriers, and more on the fly. Promote sooner, more effective management reporting and decision-making with real-time, embedded enterprise intelligence analytics and user-defined dashboards. Learn the six key parts that every one process manufacturers should look for in a better enterprise administration answer.

Let us take your organization’s digital transformation to the Third Stage. With the roll-out of Sage X3, Sage transitioned from their unique position of a “small” ERP software program to opening new doors that make it a fantastic match for mid-market corporations with extra complicated wants. They are a powerful contender within the mid-market manufacturing and distribution space and have built their reputation based on their focus throughout the trade. Sage X3 permits you to simply handle sales and buyer data throughout the resolution.

SAP Connect experiences by bringing data, processes and third-party systems to the SAP ecosystem. Our analysis research help our purchasers make superior data-driven choices, understand market forecast, capitalize on future alternatives and optimize efficiency by working as their associate to ship correct and useful data. The industries we cover span over a large spectrum including Technology, Chemicals, Manufacturing, Energy, Food and Beverages, Automotive, Robotics, Packaging, Construction, Mining & Gas.

Sage X3 for process manufacturing helps you handle your complete operation quicker and more effectively. With Sage X3 you get targeted insights into high quality and prices so you'll have the ability to efficiently fill buyer orders, optimize manufacturing planning, and ensure prime quality. For most businesses, crucial information, insight, and indicators are scattered about–in spreadsheets, methods, and databases. In some instances, employees themselves turn sage x3 manufacturing into gatekeepers of data others want, which may trigger bottlenecks. Supply chain managers can monitor inbound and outbound stock with unimaginable element, and that visibility allows manufacturers to react instantly to changes. Sage X3 schedules can be more sensible by incorporating quicker production times primarily based on the latest improvements on the shop floor.

The benefits that Sage X3 clients get are, it helps the business processes right into a unifying design with ease. It streamlines the workflow and allows the collaboration between the vendors and customers. If you're on a lookout to get in contact with the Sage X3 prospects, InfoClutch’s Sage X3 prospects record will be the proper option. Sage Business Cloud X3 is a manufacturing software that has a simple interface for even essentially sage x3 manufacturing the most inexperienced customers. It's configurable to satisfy distinctive enterprise needs and is provided with bountiful options corresponding to accounting, reporting, fixed assets, inventory management and extra. Although some customers say the design is old style they usually obtain too many error messages, Sage X3 is still a productive and sturdy device to implement.

Sage X3 ERP fixed asset also comes included with several depreciation fashions, lifecycle management, inbuilt reporting and financing. It is the solution cloth that digitalizes all workflows across a company’s worth chain, from accounting and budgets to manufacturing and customer service. Sage X3’s versatile knowledge mannequin captures the transactions, documents, and details of those workflows in a constant and complete system of report. As a food and beverage producer, you deal with a unique set of industry-specific requirements and rules.

Various performance indicators are available, making certain optimum industrial production high quality and traceability. Sage X3 delivers real-time visibility into quality and prices so you can ensure product consistency, optimize production planning, and handle compliance throughout currencies, regions, and rules. Download the guide to find how Sage X3 can improve your processes. Workers who supported manufacturing processes, but who did not work on the store flooring might shift to distant access in the course of the pandemic - so why not think about cloud manufacturing?

0 notes

Text

Star Wars Battlefront II (the good one)

My nonfunctional internet is preventing me not only from finishing off my essay, not only from watching the lecture that I would have shown up for were it not for mediary COVID restrictions, but it’s also stopping me from writing anything here that would require any sort of research or confirming details. That leaves me with less options that I would have thought.

Browsing through my Steam collection for ideas on what to talk about, and something jumped out at me pretty quickly.

Star Wars Battlefront II (the 2005 game, not Star Wars Battlefront 2, the sequel to the EA remake much maligned for malicious microtransactions) is a first/third person shooter that, while showing its age, remains one of the best games the franchise has ever put out. This is, of course, an opinion coming from someone who has yet to play Knights of the Old Republic, but it feels like Star Wars as a franchise has more misses than hits. So what makes this one land?

While I’m woefully unfamiliar with the early 00s shooters that Battlefront II was competing with (aside from Counter-Strike Source, but I’d argue that’s a different target market), I am extremely familiar with this one. I think part of why Battlefront II is so fondly remembered is on account of it being almost a gateway game for people getting into shooters in general- I for one played it extensively on my mate’s PS2 in primary school, and later on someone else’s PSP, and I doubt I would later have clicked so strongly with Halo if I hadn’t.

But what Battlefront II has more than anything else I feel is ambition. After the conclusion of the prequel trilogy, Star Wars’s universe was big, and the developers seemed interested in representing about as much of what we see of it’s style of warfare as they possibly could. As a result, the maps are a glorious smattering of worlds and terrains, loving and detailed recreations of places from the various films as well as a few that are probably new (I might just not remember them), each drizzled with vehicles and turrets and resources. Each of the game’s four factions share the basic units with very few differences (except for the Super Battle Droid), making them easy to understand and grasp for newer/younger players, with the complexity of each’s unique units paying off those willing to grapple with their weakness and play to their strengths. Some are definitely better than others, but that isn’t especially obvious at first. The basic classes reflect tropes seen in other games and while again some falter it’s not by enough that picking them in the wrong situation is a guaranteed blunder.

There are, of course, the heroes, major characters from the series granted to a player who’s doing pretty well, and I feel like this is another pretty well handled mechanic, even if a little awkward. There are enough of them, and they’re distributed enough between maps and factions, that they don’t tend to feel stale, and it’s pretty obvious that while they can absolutely ruin a team it’s also pretty easy to mishandle them. Unfortunately, heroes are related to one of my biggest complaints about the game, but we’ll get to that later.

One of the biggest selling points in my eyes are the dogfight levels. Now, I’ve never played X-Wing or the like, in fact my experiences with dogfighting games is extremely limited. But this part of the game fucks so hard. The design ideas begun with the class selection continue with the (admittedly small) range of starfighters you can pilot, with specialised interceptors, bombers, and landing craft to go alongside the effective all-rounders. The mode offers a variety of playstyles, between hunting down opponent’s fighters to bombing their flagships to boarding said flagships and destroying their systems from the inside. There is also the option of manually controlling the turrets, as well as acting as a gunner for someone else’s bomber/lander, but these positions are unfortunately underpowered and underexplored- they’re also, ultimately, less fun. But the dogfighting just feels right. I can’t really explain it, but moving in that 3-dimensional space feels not only satisfying but accurate to the source material in a way I don’t think any future Star Wars game has yet replicated.

I suppose the various game modes are worth discussing. Skirmishing on whatever map you want is the standard, at least in multiplayer, but there are a few unique offerings you won’t see in other modes- Hunt, where it’s a faction versus some of the series’s wildlife in a mode that always feels imbalanced towards one side or the other. There’s obviously Assault- the standard name for the space dogfights but on one ground map (Mos Eisley) it is of course the ever-popular heroes free-for-all, a chaotic mess but one where you can test out each one and figure out what their abilities actually do. But in the broader strokes, you’ve got the story, and the Galactic Conquest, as the two main other modes.

(oof, they really didnt build this with this resolution in mind huh)

That’s right, this game has a story, and it’s…okay? Ultimately it’s just a series of missions with the 501st, as they fight in the clone wars, turn on the Jedi, and ultimately become the Empire’s tool of oppression, separated by exposition. You get to run through some scenes from the movies, including the boarding at the start of the first movie and the Battle of Hoth, though some of the missions feel harder than intended- no matter how good the player is, the AI is not going to fare well in the tougher missions and you have a solid chance of ending up on your own.

Galactic Conquest is the game’s more unique selling point, being something like a basic version of Risk but with the dice-rolling battles replaced with Star Wars Battlefront II. You earn credits over time and through victory that you can spend unlocking types of units, getting new fleets to improve how many fronts you can wage war on, and unlock powerups for use in the actual battles. It’s largely fine, feeling like a bit more controlled and strategic version of just playing randoms in Instant Action, but it suffers the most from the biggest problem this game has.

The game’s truest flaw is its AI. They are dumb as a sack of potatoes, and the main thing holding the game back from perfection. And it was the early 00s so imperfect AI was to be expected, but it’s a bit more than imperfect here, I guess. Robits standing still while shooting you (or just at all, while you’re sniping them), extremely questionable vehicle and turret usage, and literally crashing starships into you, your flagship, or their own flagship. Bumping their difficulty up doesn’t really help, either. Even more egregious is the AI’s usage of heroes- or rather, that they don’t. If you’re playing single player, the game will always give earned heroes to you rather than your robot teammates, will not let one of them take if it if you decline to use the character, and you will never see one on the opposite side. This would imply that there wasn’t code for the Ais to use them, except there clearly is because Assault Mos Eisley exists- and they’re arguably much better there than in any other mode! It’s a real shame, because the low quality of the AI combined with the nature of the games means that victory is extremely polarised based on the player’s skill- if you bad all the way up to pretty decent at the game, your input basically doesn’t affect the outcome, whether you win or lose. If you’re good at the game, you will never lose at singleplayer, possible exception again being Assault Mos Eisley. It’s a little absurd, honestly. Also, I’m not even sure they go for the flag in CTF in space.

I am, however, willing to look past these flaws. The game is far from perfect, but it’s just incredibly fun. It’s a type of gameplay that they’ve tried to replicate, but never quite recaptured- and I think part of the reason for that is because the awkwardness is part of the charm. It’s nostalgic- both for those who played it when they were younger and just those in my generation who grew up on the Prequels. It’s also way more expensive on steam (bruh 14.5 AUD for real?) than I expected, but it goes on hard sales pretty often (I think I paid like a buck fifty for it), so it’ll be within budget at some point. I don’t know if I can recommend it for those who aren’t nostalgic, though, solely on account of those awkward features you likely wouldn’t be able to ignore like I do. And that’s a shame, because it’s not like they’ve made a better version of this game.

Fuck EA, basically.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Motif Way 4: Core Motif Engine Oracles

Core Motif Engine Oracles is the 4th in a series of articles about "The Motif Way",

the philosophy & design principles behind the Motif Framework and Runs On Motif games.

As promised, we finally come to the core mechanic underpinning the Motif Story Engine and Runs on Motif games! The basic Motif Engine oracle is a 3d6 roll. It uses common six-sided dice almost everyone has and available even at corner stores and pharmacies. Each die represents a different factor for the roll. But why? What is the actual approach?

What are RPG "Oracles"?

Oracle is a term that gained popularity with GM-emulators, GM-less games, and solo RPGs. It is a dice roll, card draw, word dice throw, or other randomizing element used as a world or response generator. A Magic 8-Ball and Tarot readings are common examples of oracles used outside of roleplaying games. RPG oracles are used to generate answers like a storyteller and provide idea seeds for GM or player use.

They different from typical roleplaying dice rolls in the depth of answer and being designed to answer questions, rather than model success probabilities. Some regular roleplaying game tools, like random encounter generators and core dice systems providing complex answers, could be considered oracles or to straddle the line between traditional RPG rolls and roleplaying oracles.

In Runs On Motif games or sessions using the Motif Action Engine toolkit, they serve double duty as the both a story engine (GM-emulator) and as a resolution mechanic or core roleplaying system. The rolls are structured much the same. The primary differences are that character capabilities may affect the roll and that the answers are about player character actions, instead of world details and reactions. But it is essentially the same oracle set powering the answers.

Why Use Dice Oracles?

An oracle approach is ideal for solo RPG, GM-emulator, and narrative approaches to roleplaying games. The flexibility and basic setup favors emergent results heavy on genre and theme. The Q&A setup encourages thinking about the action in context and the overall emerging story.

When used as a resolution system, an oracle style approach provides a different play flow and experience. Oracles provide a different feel from traditional roleplaying, even where mathematically equivalent. The classic roleplaying system typically frames things in terms of target numbers, probabilities, and binary action resolution. Some lean toward a more oracle-like approach with degrees of success or exceptional success and failure. But they usually approach things in a "mechanical" or calculation-centered way.

Dice oracles place the emphasis on answering questions in context of the narrative. Rather than asking if you hit a target number or crunching the numbers in a system, you directly ask questions about the action and story. Ideally, a robust oracle system will provide nuanced or complex answers. Instead of asking if you hit a defense rating of X and matching numbers, you ask the oracles how well your attempt to fend off the intruder with your sword goes. Instead of rolling to see if you succeed on a perception check against a difficulty level of X, you ask the oracles if your character perceives any threats in trees. Even when using the same basic mechanics, it encourages both players and GMs to think of rolls and results in a different way.

The term "oracles" itself helps in the same way as we noted genre and themes help drive play. People often think of dice as random number generators and probability models. Thinking of a dice oracle as a kind of answer engine, mock AI, or even GM-emulator yields a different result in the flow of play. The term lends itself to that through awareness, even if by vague association or in name only, of varied things like seance boards, magic 8-balls, and the Oracle of Delphi. The natural emphasis on story grounding and the flexibility of questions is a strength in roleplaying games.

Main Motif Oracles

The main oracles are a set of three simple six-sided dice with each representing a factor. The first die is the flat answer. The second die is strength or degree of answer. The third die is a special die with plug and play options called "flavors". We count them first to third from left to right or closest to farthest.

Overall on Motif rolls, low is no, negative, none, or a similar result. In contrast, high is a yes, positive, many/lots, or a similar result. 3-4 in the middle can be used middling or mixed answers and outcomes.

On the first die, it can answer any question that can be answered no/maybe/yes or fail/mixed/success. On the second die, low is weak or little and high is strong or a lot. The third "flavor" die is a descriptor like favorability or weirdness; low is absent or contrary and high is omnipresent or extreme.

Say we ask the oracles with a favorability flavor, "Is there a back exit here?" We roll 4, 6, 2. That's a high strength mixed answer with low favorability. There is one but it has been unused for a long time and is blocked by old boxes and storage shelves. Or we could ask the oracles with a weirdness flavor if cultists are in the area. We roll 5, 3, 1. That's a medium strength yes with the contrary of weirdness (which in this context is ironically weird). There is indeed a gaggle of cultists. They are having a cookout. Perhaps it is the gathering before the bizarre ritual, but it is surprisingly mundane.

Answer Variations

The first die can be read as a binary answer, a simple yes or no. This is good to "devolve" to when mixed answers would be confusing. Simple move the 3 to the "no" end and

But the real secret is that the die can answer any two or three outcome answer. This could be as simple as coming to a fork in the river and asking if the bad guys being chased go left or right. It could also be the answer when there are 2 or 3 distinct possibilities. For example, say a crime lord has three main assistants. Who is "on duty" when you arrive cause trouble? Assign the first option to 1-2, the second to 3-4, and the last to 5-6. Anything you can boil down into two or three main choices can be done with the answer die.

Strength Variations

Instead of pure degree or strength of answer, there are many variations that still measure the strength of the response. One simple example is interpreting the second die as a narrower type of strength. Rather than amount or degree, you can change the emphasis to intensity. It is good when the overall strength or amount is a known or obvious factor. We know there is a large angry crowd, but how intense are they? A slight variation of the same concept could be used to set the stakes or judge how much wiggle room in time to act.

Another example of a strength focus is firmness. Rather than judging how intense or how much, it suggests how wholly true or resilient the answer is (how "firm" it is). A low result suggests the answer is uncertain, temporary, or easily changed. A high result suggests it is a firm fact and unlikely to change in the foreseeable action.

Another approach is moving away from a number scale to "purer" answers. Assign "but" to 1-2, flat or simple answers on 3-4, and "and" with 5-6. This combines with the first die for "yes but", "yes and", "no but" and so on answers. It fulfills the key function of the die (answering the strength of answer) in a more improv or guided way. It trades the granularity and sense of scale of straight die results for the storytelling emphasis of "but" and "and". It is ideal for free-flowing games with a heavy storytelling tone.

A variation the but/and option is instead going with penalty/bonus or disadvantage/advantage. Instead of "but" read it as a cost or disadvantage. Instead of "and" read it as a bonus or gained advantage. For many RPGs, this better fits the play flow and/or helps highlight the dramatic action. Some players also have a preference of thinking in terms of risk and reward or cost/benefit, but still wish to explore more narrative styles of gaming.

Interpreting Rolls

When interpreting rolls, keep in the context. What does it mean in a given genre of story? How does the level of zoom and what came before change the feel and nature of the answer? Hold onto your basic assumptions and the game flow when interpreting answers.

If you are a secret agent and breaking into a supervillain's compound, you don't need a chart or special roll to tell you guards and minions are the likely foes. That is something you just know because you're playing a secret agent game and attacking a villain's headquarters. If you get a "yes" when asking if opponents are around, you know they are such villainous agents. If you get a weak answer and/or strong favorability, you may encounter but one or two weak guards. A middling result might be monstrous "pet" or security team, depending on the kind of villain. (Context!) A strong or unfavorable result may be a large force led by one of the "named" lieutenants of the Big Bad.

Getting into less clear results, what about a mixed/maybe answer with a middling strength and favorability? Sounds unclear or muddled at first to some people. Still following the same example, keep it simple and stay in context. We are in the villain's lair and worried about their followers. So there is a mid-size crowd nearby but not in the immediate area. They are around the corner doing a training exercise. The protagonist(s) can ambush them or has a good chance to sneak by.

Another one that can be confusing at first is when you get dice results that seem contrasting. As a different example, say we have adventurers who are trying to escape a labyrinth after defeating a necromancer. Their questions are generally focused on details that would help them get out. They have established the walls cannot be scaled and cannot be penetrated. They are asking about fresh paths to follow.

One answer is a strong "no" with a high favorability. How can a dead end be favorable!? Generally, you can let character actions and questions determine the answer. The PCs may decide to look for clues of obscured or hidden paths. Or perhaps they think aloud that the traps and creatures need maintenance and start looking for small hatches and portals in the ceiling and floor. Give them a boost and/or offer new options to reflect the favorable circumstances. If it is a very high favorability result, you may skill any checks and simply point out the features as a result of their general search.

The general idea is to let the overall setting and game flow naturally answer the questions. Do not overthink it. Keep it simple. The moment your intuition or knowledge has an answer, go with it. A big part of learning to use oracles and play GM-less or solo is learning to let go and let the flow do the hard work. Answers will seem clearer and there will be fewer opportunities to feel stuck.

What if we have confusing or contradictory results in solo or when the players are stuck? Briefly think of the context and flow of things. If an answer is not forthcoming, you can do a few different things. You can "devolve" the roll. If a mixed answer is confusing, count a 4 as yes/high and 3 as no/low. You can reroll to see if a different result is clearer. If you have a good idea for what the answer should be, you can just follow that. Or you can skip over the question and move on the next thing. There is no reason to stop play for one roll. Keep things moving.

We said all that and still have not talked about about flavors. What about them? Do not worry! We are talking all about flavors and how to use them in our next entry in the Motif Way series!

The Motif Way Series

1: Emergent Sandbox Roleplaying

2: Genre Rooted, Themes Supreme

3: RPG Focus and Flow

4: Core Motif Engine Oracles

5: Adding in That Storytelling Flavor

6: Hackable RPGs, Modular Systems, and Other Buzzwords

7: Patching Motif

8: Narrative Consequences in RPGs

9: Story First, Dice Last

- 10: Devolving Dice Rolls & RPG Systems

Motif Way Extras

- Why Player Facing Rolls?

Read the full article

#adventure#Design#Dice#Divination#Emergence#Emulator#Gamebalance#Gameengine#Gamemechanics#Gamemaster#gm-less#GMs#Intuition#KISSprinciple#Magic8-Ball#Mechanics#Motif(narrative)#motifactionengine#motifstoryengine#Narrative#Oracle#oraclesystem#Perception#Philosophy#Question#Role-playinggame#roleplayinggametools#solorpg#solorpgs#storyengine

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conversion Kit: The Assassin

Continuing my Conversion Kit series of articles, we discuss the Assassin subclass! Turn any character into a master of ambushes and terribly efficient killer with just three levels of Rogue.

Below the readmore, you can find Additional Support for this kit, as well as Pitfalls and Character Suggestions.

Kit Overview

Investment Type: Multiclass Dip

Minimum Investment: Take 3 Levels of Rogue, selecting the Assassin archetype at level 3.

Overall Impact: Your character now has the mechanical backing to follow through on clever schemes with lethal force.

Investment

Much like our last conversion kit, once you select the Assassin subclass, you can immediately set off to do what assassins do best. Once again, you'll need to satisfy the multiclassing requirement- just a score of 13 in Dexterity, plus a score of 13 in whatever attribute your other class of choice requires.

You don't necessarily need a Dexterity higher than this, but remember that your bonus to Stealth rolls keys off of it. You can mitigate the problems of a low Dexterity score by taking proficiency in Stealth and using the Rogue's Expertise feature to double your proficiency bonus.

Truth be told, you can abandon Stealth entirely if it doesn't fit your concept. However, you'll want to keep in mind that the assassin's primary feature requires Surprise. While by the Rules as Written, Stealth is the only way to gain surprise, many GMs will allow betrayals or sudden strikes to grant surprise.

Perhaps you can take advantage of Deception or Persuasion to lure your target into a false sense of security, or use a spell like Dimension Door or Invisibility to suddenly appear behind (or even before) a foe and strike them down.

All that said, regardless of the method you'd like to use, you're very likely to want stealth proficiency. It's the least reliant on GM interpretation and applies to the greatest variety of situations.

Narrative Impact

Though the most apparent Narrative for a character using this kit is that of a professional murderer, it is by no means the only route you can take. Your character is now mechanically incredibly reliant on first strikes. Hunters-turned-warriors (such as most rangers) gravitate to this approach to combat by default, but characters lacking the stomach for battle might turn to this path to end fights quickly. Elite warriors might prefer ambush tactics, and even certain paladins may find a swift death to be all that their foes deserve. In truth, you could utterly ignore this kit's narrative impact and carry on as if you had never taken a single level in another class. However, I'm inclined to see that as something of a wasted opportunity to set your character apart- where did your character learn to fight dirty? Do they see it as a necessary evil and regret their actions, or do they believe they're justified as there's no justice on the battlefield?

Mechanical Impact

From a mechanical perspective, the Assassin offers lethal first-strikes. Whatever your method of attack- a greatsword, a spell, thrown dagger- your Assassinate feature guarantees you a Critical Hit, as long as the attack hits a surprised target.

I cannot emphasize enough how unbelievably good a Guaranteed Critical Hit is in Fifth Edition D&D, and believe me, if I had a way to highlight that bolded, italicized, underlined phrase I would use it. I thought about including a gif of someone slapping a desk. I need you to see those words and realize what they mean.

A critical hit multiplies all of your damage dice. If you can find bonus dice, you're going to hit incredibly hard. If you have multiple attacks, they will all be critical hits. A critical hit on a Paladin's Smite or Rogue's sneak attack is a lucky break. A full round's worth of critical hits on a Fighter's attack routine or a Wizard's Scorching Ray is a dream. Get the drop on an enemy, and that dream is your reality.

The simple truth is, the Assassinate feature alone is enough to enable ambushes as a tactic.

Kit Support

There are several feats you can take advantage of to make this kit more effective. However, even if feats aren't allowed in your game, or all of yours are already accounted for, you're not out of luck. If you keep some rules of thumb in mind, you'll find yourself faring better than someone who approached their build haphazardly.

This list is in no particular order. This is not an optimization guide, and I don't want to commit to the math necessary to rank these options, nor do I want to limit your creativity. That said, as an Assassin, you want to look for:

More attacks. These are easy enough to get: engage in two weapon fighting, pick a class that has the Extra Attack feature, or find a way to get Haste applied to you.

Extra dice for your attacks: Smite and Sneak Attack are good examples. If you have your eyes on a higher level Rogue feature, the extra sneak attack dice will help with this (if you're using an appropriate weapon).

Similarly, spells that grant multiple attack rolls such as Eldritch Blast or spells that have large dice counts like Chaos Bolt. Both of those can be picked up by classes that can't normally access them using the Magic Initiate feat.

You might also consider certain feats, depending on your build and game:

Alert gives you a large bonus to initiative. Depending on how your GM runs Surprise, you may need to win initiative to take advantage of Assassinate- Alert all but guarantees that you'll move first, especially if your Dexterity is already high.

Lucky adds some reliability to your assassination attempts by letting you try again when you roll poorly. Lucky is good to the point of being considered 'cheese' by the community, and many games ban it, but there is objectively no better way to ensure you don't ruin your big moment.

Skulker is somewhat similar to Lucky for ranged characters, though not as effective. If you're a ranged Assassin, this keeps your position from being revealed. You'd be hard pressed to convince your DM that the enemy is still surprised, but maybe you can retreat and try again. The other miscellaneous stealth bonuses are a nice plus.

Spell Sniper doubles your range for attack roll based spells- it'll be easier to surprise foes from a couple of hundred feat away. As a bonus, you ignore all but total cover and even get access to an attack roll based cantrip if you didn't have one already.

Actor might improve your odds of pulling off a social skill based assassin, just check with your GM to make sure they'll rule in your favor before you invest too heavily in the approach.

Pitfalls

There's not a whole lot you can do as a player to make this kit go wrong. Your biggest obstacles are overspecialization and, potentially, your DM.

In the first case, there will be times when Assassinate will fail you. Perhaps the situation isn't right, perhaps you missed your attack, maybe the enemy got the drop on you. None of that matters though- just keep in mind when making choices about your character that not everything needs to improve their critical damage. Dealing hundreds of points of damage with your first strike only matters if you pull it off.

In the second case, some DMs are combative. You might have a DM that feels as though you're somehow "cheating" by assassinating big threats and coaxing your party towards ambush tactics. Some DMs will simply grumble about it and you may need to back off somewhat.

Others will attempt to sabotage you, either by presenting scenarios that make assassinations difficult or impossible, overwhelmingly pitting you against foes that are impossible to surprise or are immune to critical hits, or, in the most egregious cases, abusing their power and arbitrarily depriving you of surprise when you should have it.

The best thing you can do here is keep a level head and talk to your DM. They likely don't actively want to ruin the game for you, and perhaps they have a reasonable motive- maybe you're taking the spotlight away from other players or even making the game less fun for the DM themselves (believe it or not, this is a reasonable concern for the DM- they should have simply been honest with you in the first place, but berating them now won't help either of you).

Whatever your DM's reasons, you can likely compromise if they're honest with you. If your DM gives you any variation of "this is your fault for picking a specialized feature" or "it's just the way it is", you may need to ask if you can rebuild, as they're unlikely to sympathize with your position. Ultimately, your playstyle may just not align with the DM's or group's. There are hundreds of articles about conflict resolution, some specifically tailored for D&D groups, so for the moment I'll table the specifics and perhaps update this article with a link to a quality one at a later date.

A Few Suggestions

I don't want to leave this article on a low note, so I'll close with some classes you can combine with the Assassin subclass for some exciting (if somewhat obvious) character concepts:

Way of Shadow Monk: This monk path offers several supernatural abilities relating to darkness, silence, and hiding- not the least of which is the ability to teleport between patches of shadow. If that doesn't scream "ninja" to you, I don't know what will. The monk also has access to Flurry of Blows, which can make your assassinations quite potent.

Oath of Vengeance Paladin: The Paladin's Smite might be the easiest on-demand way to take advantage of your Assassinate feature. Very few of this Archetype's features synergize with this kit, but access to Haste and Hunter's Mark doesn't hurt, and the narrative of an avenger fits well with the style of combat you'll be employing. If you liked Pathfinder's inquisitor class, this may be for you.

Fiend Patron Warlock: Eldritch Blast is always good, but you have an extra edge with it. Honestly, there's not much too this other than having an easy on-demand ranged damage option, but something about being a contract killer for your Patron seems like an exciting narrative. Works just as well for other patrons, but the fiend seems most likely to employ contract killers. You can take the Blade Pact Boon and Eldritch Smite invocations if you want to step on the Paladin's turf.

With some examples out of the way, I'll take my leave. There's near limitless potential for this kit, as there's some synergy to be had with nearly every class, so you can experiment with confidence.

#rogue#rogue archetype#roguish archetype#dnd#dnd 5e#d&d#d&d 5e#5e#dungeons and dragons#dungeons & dragons#conversion kit#assassin#multiclass#fifth edition#5th edition

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

So I’m currently playing as a CG bard in a homebrew campaign, and I just made the questionable decision of becoming a paladin of a LE god. This act requires me to lie in character more than I’m used to, and as a person I am a reeeaalllly bad liar. In terms of role play, do you have any tips on role playing as something that you aren’t good at? My character has a good deception modifier, but I can’t lie to save my life which makes everything so much more difficult. I’m a little lost! 😅

Thanks for submitting your question, pachelbels-passacaglia! I’ve fallen behind on my Q&A and this is a fantastic way to jump back in.

As I read the question, I’m thinking it’s really asking two things.

What can I do to better roleplay a character who is not like me?

How can I play as a character who is capable of something that I am not?