#segregation in america

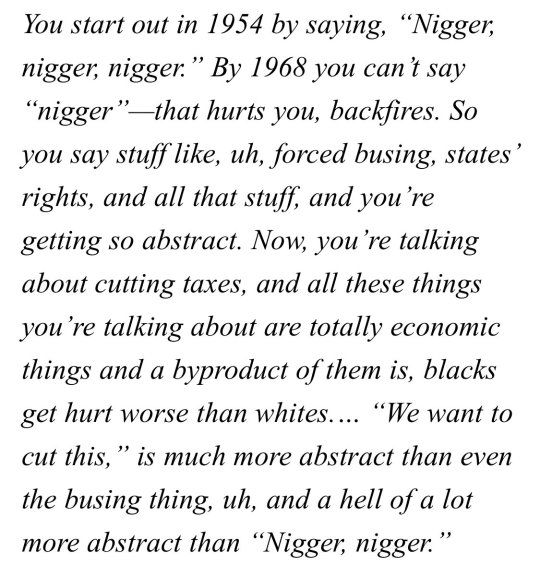

Text

https://x.com/PDeniseLong/status/1702030861565096045?t=LUg3PzqI1pP6EBXNfVV3ug&s=09

#gop racism#freedmen#voting while Black#13th amendment#14th amendment#Jim Crow#white supremacy#Freedmen#Black Freedmen#anti slavery#segregation in america

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

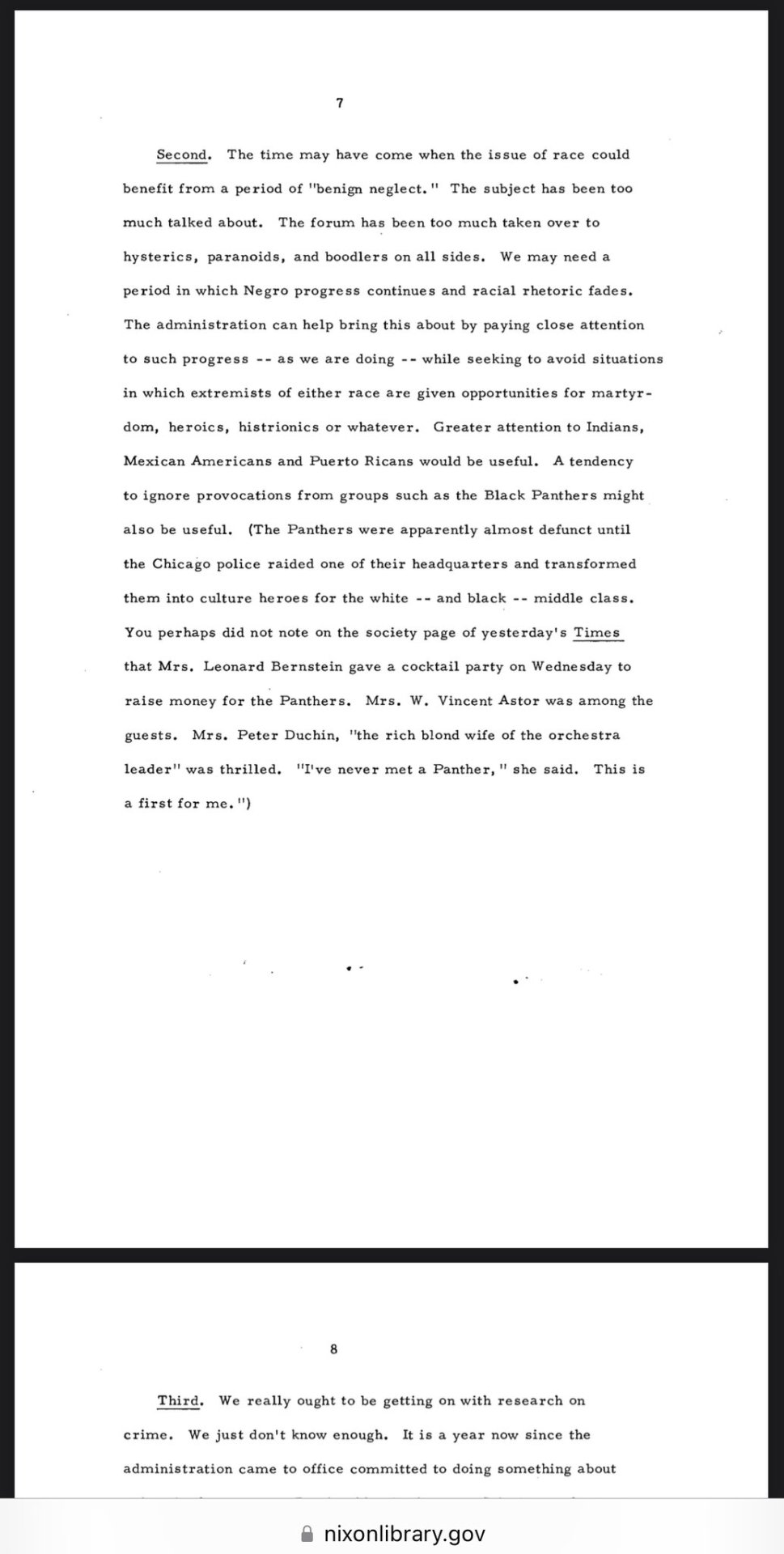

"The First Lesson.

This way the society in which vices reign gives the child their first lessons."

Soviet Union

1964

#propaganda#poster#vintage#imperialism#capitalism#communism#socialism#america#usa#united states#segregation#kkk#racism#racist#klu klux klan#lynch#south

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking about the parallels and differences between Marie Levesque's relationship with Pluto and Maria di Angelo's relationship with Hades

In both flashbacks, we see Hades/Pluto trying to convince them to stay/go somewhere for their and their children's protection and both women refuse his request, but where those scenes differ is in how they respond to him

Maria is so patient and loving towards Hades. She never raises her voice, she repeatedly calls him my love, and yet is firm about not raising their children in the underworld. She only sees the good in Hades - calls him kind, generous, insists the other gods wouldn't be afraid of him if they saw him the way she does. She has unwavering faith that he will protect her, and won't allow any harm to come to Nico and Bianca. There is actual love there, and we get the sense that they did have a good relationship despite him being a god

Queen Marie, on the other hand, deeply resents Pluto. She's angry to the point of throwing and breaking things around her home, and blames him for all of their misfortune. It's Pluto's fault that Hazel is cursed, it's Pluto's fault that people around them are dying, it's Pluto's fault that the police thinks she's a murderer and her clients think she's a witch. Unlike Maria, Queen Marie doesn't believe that Pluto has ever protected them, nor does she want him to, not after how much he has ruined her and Hazel's life. There's little love there like with Maria and Hades, little trust - just bitter angry resentment.

And it makes sense that they would react so differently! We don't get the sense that Hades's godhood has affected Nico or Bianca in any tangible way (at this point, anyway). They're playing together when Hades visits Maria and seem happy. They're not cursed the way Hazel is. They don't have dangerous and harmful powers that they can't control (that we know of). Of course Queen Marie would resent Pluto in ways that Maria doesn't; the wish Pluto granted Queen Marie has actively made their life worse. The di Angelos were fine. The di Angelos were thriving. They had nothing to worry about until the Great Prophecy was issued, and Maria had no reason to believe that Hades couldn't protect them from Zeus when he had protected them thus far. He hadn't done anything to hurt her the way that Queen Marie believed Pluto hurt them.

But here's the thing though: Queen Marie was being manipulated by Gaia. Both she and Pluto tell Hazel that The Voice turned her against him. Just before Queen Marie and Pluto speak to each other in the first flashback, we see her push back against Gaia's request to go to Alaska precisely because Pluto told her it wasn't safe and that he wouldn't be able to protect her and Hazel there. Gaia was the one who convinced her that it was Pluto's fault that Hazel was cursed; after all, it's much easier to blame him than to admit to herself that it was her wish and her greed for "all the riches in the world" that lead to Hazel's predicament.

Gaia preyed on Queen Marie's frustration with herself and with Pluto to manipulate her into bringing Hazel to Alaska to raise her son from the earth. It was this manipulation that lead her to blowing up at Pluto when he tries to convince her to stay in New Orleans. Maria didn't hate Hades because the gods didn't torment her the way Gaia tormented Queen Marie.

Which raises the question: if Gaia hadn't messed with her head, would Queen Marie have loved and trusted Pluto the way Maria loved and trusted Hades? Could Pluto and the Levesques have played happy families the way the di Angelos did with Hades? It's more complicated because Gaia's absence would not have fixed Hazel's curse so it's entirely possible she still would have resented him, but I have to wonder:

Was there ever a world where the Levesques could have been happy?

#maria di angelo#marie levesque#hazel levesque#nico di angelo#bianca di angelo#pjo#meta#mine#also something to be said about how pluto presents as a rich white man#and as two black women in segregated america queen marie and hazel would have every reason to distrust him#in ways that an italian daughter of a diplomat like maria wouldn't feel towards Hades

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

On May 28, 1914, the Institut für Schiffs-und Tropenkrankheiten (Institute for Maritime and Tropical Diseases, ISTK) in Hamburg began operations in a complex of new brick buildings on the bank of the Elb. The buildings were designed by Fritz Schumacher, who had become the Head of Hamburg’s building department (Leiter des Hochbauamtes) in 1909 after a “flood of architectural projects” accumulated following the industrialization of the harbor in the 1880s and the “new housing and working conditions” that followed. The ISTK was one of these projects, connected to the port by its [...] mission: to research and heal tropical illnesses; [...] to support the Hamburg Port [...]; and to support endeavors of the German Empire overseas.

First established in 1900 by Bernhard Nocht, chief of the Port Medical Service, the ISTK originally operated out of an existing building, but by 1909, when the Hamburg Colonial Institute became its parent organization (and Schumacher was hired by the Hamburg Senate), the operations of the ISTK had outgrown [...]. [I]ts commission by the city was an opportunity for Schumacher to show how he could contribute to guiding the city’s economic and architectural growth in tandem, and for Nocht, an opportunity to establish an unprecedented spatial paradigm for the field of Tropical Medicine that anchored the new frontier of science in the German Empire. [...]

[There was a] shared drive to contribute to the [...] wealth of Hamburg within the context of its expanding global network [...]. [E]ach discipline [...] architecture and medicine were participating in a shared [...] discursive operation. [...]

---

The brick used on the ISTK façades was key to Schumacher’s larger Städtebau plan for Hamburg, which envisioned the city as a vehicle for a “harmonious” synthesis between aesthetics and economy. [...] For Schumacher, brick [was significantly preferable] [...]. Used by [...] Hamburg architects [over the past few decades], who acquired their penchant for neo-gothic brickwork at the Hanover school, brick had both a historical presence and aesthetic pedigree in Hamburg [...]. [T]his material had already been used in Die Speicherstadt, a warehouse district in Hamburg where unequal social conditions had only grown more exacerbated [...]. Die Speicherstadt was constructed in three phases [beginning] in 1883 [...]. By serving the port, the warehouses facilitated the expansion and security of Hamburg’s wealth. [...] Yet the collective profits accrued to the city by these buildings [...] did not increase economic prosperity and social equity for all. [...] [A] residential area for harbor workers was demolished to make way for the warehouses. After the contract for the port expansion was negotiated in 1881, over 20,000 people were pushed out of their homes and into adjacent areas of the city, which soon became overcrowded [...]. In turn, these [...] areas of the city [...] were the worst hit by the Hamburg cholera epidemic of 1892, the most devastating in Europe that year. The 1892 cholera epidemic [...] articulated the growing inability of the Hamburg Senate, comprising the city’s elite, to manage class relationships [...] [in such] a city that was explicitly run by and for the merchant class [...].

In Hamburg, the response to such an ugly disease of the masses was the enforcement of quarantine methods that pushed the working class into the suburbs, isolated immigrants on an island, and separated the sick according to racial identity.

In partnership with the German Empire, Hamburg established new hygiene institutions in the city, including the Port Medical Service (a progenitor of the ISTK). [...] [T]he discourse of [creating the school for tropical medicine] centered around city building and nation building, brick by brick, mark by mark.

---

Just as the exterior condition of the building was, for Schumacher, part of a much larger plan for the city, the program of the building and its interior were part of the German Empire and Tropical Medicine’s much larger interest in controlling the health and wealth of its nation and colonies. [...]

Yet the establishment of the ISTK marked a critical shift in medical thinking [...]. And while the ISTK was not the only institution in Europe to form around the conception and perceived threat of tropical diseases, it was the first to build a facility specifically to support their “exploration and combat” in lockstep, as Nocht described it.

The field of Tropical Medicine had been established in Germany by the very same journal Nocht published his overview of the ISTK. The Archiv für Schiffs- und Tropen-Hygiene unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Pathologie und Therapie was first published in 1897, the same year that the German Empire claimed Kiaochow (northeast China) and about two years after it claimed Southwest Africa (Namibia), Cameroon, Togo, East Africa (Tanzania, Burundi, Rwanda), New Guinea (today the northern part of Papua New Guinea), and the Marshall Islands; two years later, it would also claim the Caroline Islands, Palau, Mariana Islands (today Micronesia), and Samoa (today Western Samoa).

---

The inaugural journal [...] marked a paradigm shift [...]. In his opening letter, the editor stated that the aim of Tropical Medicine is to “provide the white race with a home in the tropics.” [...]

As part of the institute’s agenda to support the expansion of the Empire through teaching and development [...], members of the ISTK contributed to the Deutsches Kolonial Lexikon, a three-volume series completed in 1914 (in the same year as the new ISTK buildings) and published in 1920. The three volumes contained maps of the colonies coded to show the areas that were considered “healthy” for Europeans, along with recommended building guidelines for hospitals in the tropics. [...] "Natives" were given separate facilities [...]. The hospital at the ISTK was similarly divided according to identity. An essentializing belief in “intrinsic factors” determined by skin color, constitutive to Tropical Medicine, materialized in the building’s circulation. Potential patients were assessed in the main building to determine their next destination in the hospital. A room labeled “Farbige” (colored) - visible in both Nocht and Schumacher’s publications - shows that the hospital segregated people of color from whites. [...]

---

Despite belonging to two different disciplines [medicine and architecture], both Nocht and Schumacher’s publications articulate an understanding of health [...] that is linked to concepts of identity separating white upper-class German Europeans from others. [In] Hamburg [...] recent growth of the shipping industry and overt engagement of the German Empire in colonialism brought even more distant global connections to its port. For Schumacher, Hamburg’s presence in a global network meant it needed to strengthen its local identity and economy [by purposefully seeking to showcase "traditional" northern German neo-gothic brickwork while elevating local brick industry] lest it grow too far from its roots. In the case of Tropical Medicine at the ISTK, the “tropics” seemed to act as a foil for the European identity - a constructed category through which the European identity could redescribe itself by exclusion [...].

What it meant to be sick or healthy was taken up by both medicine and architecture - [...] neither in a vacuum.

---

All text above by: Carrie Bly. "Mediums of Medicine: The Institute for Maritime and Tropical Diseases in Hamburg". Sick Architecture series published by e-flux Architecture. November 2020. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Text within brackets added by me for clarity. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

#abolition#ecology#sorry i know its long ive been looking at this in my drafts for a long long time trying to condense#but its such a rich comparison that i didnt wanna lessen the impact of blys work here#bly in 2022 did dissertation defense in architecture history and theory on political economy of steel in US in 20s and 30#add this to our conversations about brazilian eugenics in 1930s explicitly conflating hygiene modernist architecture and white supremacy#and british tropical medicine establishment in colonial india#and US sanitation and antimosquito campaigns in 1910s panama using jim crow laws and segregation and forcibly testing local women#see chakrabartis work on tropical medicine and empire in south asia and fahim amirs cloudy swords#and greg mitmans work on connections between#US tropical medicine schools and fruit plantations in central america and US military occupation of philippines and rubber in west africa

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ernest C. Withers, “A sign outside the Memphis City Zoo” (ca. 1959)

Instead of desegregating the Memphis Zoo and allowing guests in regardless of race, one day out of the year was set aside for Black Americans to visit.

#art#photography#blacklivesmatter#human rights#ernest C. whithers#zoo#menphis#1959#1960s#equal rights#america#black history#afro american#segregation#equality

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

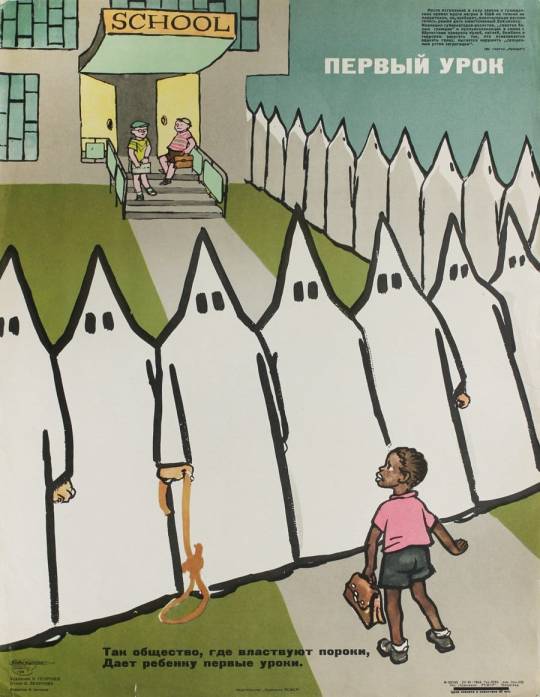

On November 7, 1931, Dean Juliette Derricotte of Fisk University in Nashville was driving three students to her parents' home in Atlanta when an older white man driving a Model T car suddenly swerved and struck Derricotte's car, overturning it into a ditch.

The driver stopped to yell at Derricotte and passengers for damaging his own vehicle, then left the scene without rendering any aid. Others tried to get care for the injured Black passengers, but the nearby Hamilton Memorial Hospital in Dalton, Georgia-a segregated facility-refused to admit African American patients. Instead, Ms. Derricotte and the three students were treated by a white doctor at his office in Dalton.

Though Derricotte and one of the students, Nina Johnson, were critically injured, following their treatment they were left to recuperate in the home of a local African American woman.

Six hours after the accident, one of the other students who sustained less serious injuries was able to reach a Chattanooga hospital by phone, and arrangements were made to transport Derricotte and Johnson to that facility, which was 35 miles away. However, the delay proved fatal. Derricotte died on her way to the hospital, at age 34, and Johnson died the next day.

The Committee on Interracial Cooperation opened an investigation into the incident, and Walter White, secretary of the New York-based NAACP, traveled south in December 1931 to learn more. He later concluded, "The barbarity of race segregation in the South is shown in all its brutal ugliness by the willingness to let cultured, respected, and leading colored women die for lack of hospital facilities which are available to any white person no matter how low in social scale."

•••

El 7 de noviembre de 1931, la Rectora Juliette Derricotte de la Universidad Fisk ubicada en Nashville, estaba llevando a tres estudiantes a la casa de sus padres en Atlanta cuando un hombre mayor blanco conduciendo un auto modelo T de repente se desvió, pegándole al auto de Derricotte y volcándolo en una zanja.

El conductor se detuvo para gritarle a Derricotte y los pasajeros por haber dañado el carro que el mismo dañó, luego se fue de la escena sin brindar ningún tipo de asistencia. Otros intentaron obtener cuidados para los pasajeros negros que estaban heridos, pero el hospital más cercano, Hamilton Memorial Hospital en Dalton, Georgia era un centro segregado que se negaba a ingresar a pacientes afroamericanos. La señorita Derricotte y los tres estudiantes fueron tratados en una clínica por un doctor blanco.

A pesar de que Derricotte y una de las estudiantes, Nina Johnson estaban en estado crítico, después de recibir tratamiento fueron dejadas para recuperarse en la casa de una mujer afroamericana de la localidad.

Seis horas después del accidente, uno de los otros estudiantes que sostuvo heridas menos severas logró contactarse por teléfono con un hospital en Chattanooga, y se hicieron arreglos para que Derricotte y Johnson fueran transportadas a este centro, el cual estaba a 35 millas de distancia. Sin embargo, la tardanza fue fatal. Derricotte falleció en camino al hospital con 34 años de edad y Johnson falleció al día siguiente.

El comité de Cooperación Interracial abrió una investigación y Walter White, secretario de la NAACP basada en Nueva York (Asociación Nacional para el Progreso de la Gente de Color) viajó al sur en diciembre de 1931 para saber más. Luego concluyó: “La barbarie de la segregación racial en el sur se muestra en toda su fealdad brutal al voluntariamente dejar morir a mujeres de color que son líderes, son respetadas y cultas, todo por falta de instalaciones hospitalarias que están disponibles para cualquier persona blanca sin importar cuán baja sea su escala social.”

#blacklivesmatter#blacklivesalwaysmatter#english#spanish#blackhistory#history#share#read#blackpeoplematter#blackhistorymonth#segregation#hospital#health#Georgia#medicine#medical segregation#black history is american history#america#newpost#new year#historyfacts#african america history#knowyourhistory#knowledgeisfree#knowledgeispower#knowledge#black women#car accident#translation#short reads

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life imitates art.

#disney zombies is my favourite allegory for racial segregation in america#will and kate are not zombies#you look delicious#oh i mean gourgeous#Zed canonically has eaten people#that is why he would fucking annihilate Troy Bolton in a fist fight

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

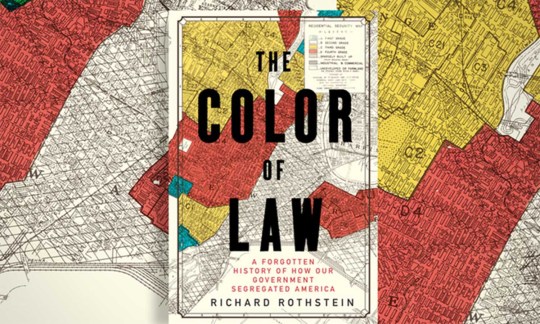

Podcast reading w/ free PDF 📚: The Color of Law~A Forgotten History of How the Government Segregated america By Richard Rothstein

The Color of Law~A Forgotten History of How Our Government:

Segregated America by Richard Rothstein Summary of book: In The Color of Law, historian Richard Rothstein notes that every single American city is segregated on racial lines and argues that this segregation is de jure rather than de facto: it is the deliberate product of “systemic and forceful” government action, and so the government has a “constitutional as well as a moral obligation” to remedy it.

Planned and implemented by all levels of American government, residential racial segregation impoverishes and disempowers African Americans by confining them to ghettos and blocking them out of homeownership. And this segregation continues well into the 21st century. Since residential segregation pertains to where and how people live their lives, the issue is harder to undo than injustices like the deprivation of voting rights, public services, and equal legal protection to African Americans. To make matters worse, governments, financial institutions, and the real estate industry continue to actively segregate American cities, to African Americans’ disadvantage.

"In Chapter One, Rothstein illustrates the problem of de jure segregation with the representative story of Frank Stevenson, an African American man living in Richmond, California in the mid-20th century. A former manufacturing town, Richmond grew rapidly during World War II. To keep up with demand, the government built public housing—for white people, it built a comfortable suburb called Rollingwood, but black working families were crowded into “poorly constructed” apartments in industrial neighborhoods, or even left to live on the street. Stevenson worked at a Ford Motor factory, which was soon relocated an hour away to Milpitas after the war. Stevenson was out of luck, because it was impossible for black people to live in Milpitas: Federal Housing Administration (FHA) funds were only allocated to all-white neighborhoods, so while housing options multiplied for white people in places like Milpitas, nobody built housing for African Americans. African Americans were thus confined to certain neighborhoods, and those neighborhoods consequently became entirely African American over time. The government subsequently withdrew services from those black neighborhoods, turning them into the “slum[s]” that they remain today."

Read PDF:

Here!🔗

Listen on:

Spotify🔗

Youtube🔗

Follow Hosts on Twitter:

@shesunruly

@the_penandpaper

Read, Listen, Like and Share!!!

#pan african#black people#politics#coloroflaw#pdf#pdf link#audiobook#podcast#spotify#youtube#twitter#segregation#redlining#history#america#library#education

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

fndingt the UGLIEST most POOPEIST UGLY UGLY FLOWER for nyx poopoopeepee farty

#also jus woke up guys n had a dream i immgratd to america#and the school systm suckd cuz i was segregated#classrom walls wer peeling'

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The third, and equally critical component of the new penological disciplinary regime at Sing Sing was the development of techniques aimed at the discovery, classification, and eradication of sexual relations among prisoners. Sex had almost certainly been going on in prisons since the first prison was built. But the opportunity for sex had probably been much more restricted in the hard-labor prisons of the nineteenth century; and when hard industrial labor collapsed in many American prisons, as the contract system was dismantled, opportunities (and perhaps prisoners’ energy) for sex were greatly multiplied. Prison administrators of the early twentieth century appear to have known that prisoners were having sexual relations with one another. Nonetheless the subject was not openly discussed or theorized in any sustained manner.

This began to change in the 1910s. From the point of view of a penology committed to the socialization of prisoners as self-governing manly citizens, sexual relations between men posed a particularly urgent problem. Through the lens of the prevailing gender ideology of early twentieth century ... sex between men was intrinsically emasculating of at least one partner – the supposedly passive “receiver,” whether or not the sex was consensual. Such a feminized position, as it were, contradicted precisely the ideal of manly subjectivity that the new penologists sought to realize in prisoners. Added to this difficulty was the problem of “manly discipline”: The new penologists hued to an ascending, middle-class view that, rather than reflexively act on their sexual passions, men ought to channel or sublimate those passions into activities deemed socially or personally useful. On this view, then, the active or penetrative partner, although supposedly the masculine partner in the act, was failing to exercise manly self-discipline; he, too, presented a challenge to the manly ideal. In their Sing Sing laboratory, Osborne and his fellow penologists proceeded to drag prison sexuality into the light of day, examine it, and “cure” it.

Fragments of evidence from the New York prison records of the early 1910s suggest that sex among prisoners at Sing Sing and elsewhere had been happening for some years. In some instances, it involved physical coercion, but in many it did not. As James White’s report had suggested, sex was being traded for food or money as a matter of course. Various reports also suggested that, before Osborne arrived at Sing Sing, such relations mostly went unpunished, and that when a person was punished in connection with prison sex, it was usually in connection with a sexual attack. It was not the aggressor, however, who received the punishment: Any prisoner who complained to the warden that he had been coerced into sex, and any prisoner who sought protection from coerced sex, was likely to be severely disciplined, while the alleged attacker – or attackers – would probably not be disciplined at all. (One of Osborne’s predecessors at Sing Sing, Warden John Kennedy, had sometimes gone so far as to send the complainant, rather than the alleged attacker, to New York’s most feared prison – Clinton). Similarly, when Superintendent Riley heard of cases of sexual assault occurring during Osborne’s wardenship, he proceeded to order the transfer of the complainants to Clinton, which suggests that the punishment of the complainant was standard practice. Indeed, it is likely that the act of complaining, and not the act of sodomy per se, was cause for punishment in prisons of the 1900s and early 1910s.

Osborne and the new penologists broke with the usual approach to prison sex, and on a number of counts. First and most conspicuously, Osborne discoursed at some length – and in public – on what had thitherto been the taboo topic of sex in prison; in true progressive style, Osborne argued that in order to solve the problem, one had first to study and understand it. Describing sex between convicts as “vile” and as a “problem ... which should no longer be ignored,” Osborne made it clear that he considered sex between men to be one of the most serious and little-understood problems of the American prison. In his early speeches and writings on the topic, Osborne drew distinctions between different kinds of men who engaged in sex with other men. On the one hand, he explained to members of the National Committee on Prisons and Prison Labor (NCPPL), there was the man who “allows himself to be [sexually] used”; on the other, there was the man whose “passions are cut off from natural relief.” The latter, according to Osborne, was simply acting on an “ordinary” sexual impulse that, because of the deprived conditions of incarceration, had been directed toward a man, rather than a woman. As Osborne wrote in Prisons and Commonsense, “Here is a group of men – mostly young and by no means deficient in the natural passions of youth – but cut off from the natural means of satisfying them.” Osborne refined this rather crude typology a few years later, in a tripartite taxonomy recalling Sigmund Freud’s 1909 classification of inverts in Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality: According to Osborne, in prisons one found the “degenerate,” whose “dual nature” made him the passive (and therefore feminine) partner of active, masculine men; the “wolves,” a popular term that Osborne appropriated to describe aggressive men who consistently preferred men to women; and the “ordinary men,” whose incarceration deprived them of their “natural” sex outlet – sex with women – and who consequently made use of other prisoners as “the only outlet” they could get.

Finding ways to channel the natural passions of “ordinary” men and youths turned out to be one of Osborne’s key projects at Sing Sing: Indeed it was a recurring theme of his wardenship. Osborne developed several tactics in his fight against the “vile” practice: He emptied the cellblock of the surplus of prisoners (whom he installed in a dormitory), so as to ensure that there was only one man per cell; he attempted to direct the natural passions of the supposedly ordinary men to nonsexual activities; he implored the Mutual Welfare League to police prisoners’ sexuality and to “condemn vice and encourage a manly mastery of the passions;” he set about identifying and isolating both the “degenerate” men who offered themselves as passive partners and the “wolves” who actively preferred other men; and he redoubled his efforts to smash the underground economy that James White had identified as a principal stimulant of prisoners’ sexual relations. (According to White, the systematic theft and underdelivery of prison provisions led to hunger among the prisoners, who then sold sexual favors for cash, and used the cash to buy the stolen food on the prison’s black market).

This latter tactic was especially crucial in Osborne’s strategy. As Osborne put it, every prison had “some degenerate creatures who are willing to sell themselves, any time, for a few groceries,” and the key to the prison sex problem in general was to ensure that prisoners were, on the one hand, well fed (and therefore not in need of procuring cash for extra food), and, on the other, afforded appropriate mental, physical, and spiritual outlets for their natural passions. In theory, the reconstitution of every prisoner as a waged consumer and producer in a simulated economy would ensure that the prisoner was no longer in a position of emasculating dependence. As long as convicts were eating well, engaging in a market economy that rewarded hard work and promoted financial responsibility, and sublimating their life force in educational and recreational activities, Osborne reasoned, the sex market in prisons would lose both its buyers and sellers.

Osborne’s conceptualization of the prison sex problem underscored the new penology’s central commitment to innovating various disciplinary activities that would absorb and direct prisoners’ energies in the face of limited industrial and other forms of labor. As the new penologists saw it, plays, motion pictures, lectures, musical events, and athletics not only addressed the problem of underemployment and initiated prisoners into the personality-building pasttimes of the ideal citizen, they sublimated the libidinal drive of the ordinary convict. Indeed, Osborne established a number of new activities at the prison in the name of vanquishing the “unnatural vice” that the prison investigators had documented in the early 1910s. Prisoners converted a basin in the Hudson River into a large swimming pool in 1915, because, as Osborne put it, swimming was a “practical method of reducing immorality” and an activity in which prisoners would “work off their superfluous energies. ... and head off unnatural vice.” (Four hundred prisoners per day were working off their “superfluous energies” in the pool by 1916). One of Osborne’s support committees, The New York State Prison Council, reiterated this point in defending the innovation of moving pictures, lectures, concerts, and other stimulating activities at Sing Sing. “These were established not as Amusements;” the Council explained somewhat defensively, “but as a definite means to an End” (caps in original): That end was “keeping the men out of vermin-ridden cells and of stimulating their minds – inured to the gray and sodden monotony of Prison walls.”

It was in no small part to combat prison sex that Osborne and the new penologists paved the way for the introduction of psychiatric and psychological testing to Sing Sing in 1916. Osborne and his supporters considered psychomedical study a crucial tool in their efforts to more accurately classify prisoners and to develop a specialized state prison system; to the classificatory system that administrators had established in the 1890s (and which classified and distributed convicts according to sex, age, sanity, physical fitness, and supposed capacity for reform), the new penologists added the distinctly psychological categories of sexuality and personality. In their view, sexual “degenerates” were a distinct category of prisoner and the prison system ought to identify and deal with them separately. Whereas the new recreational activities, better food, and prisoner self-policing were aimed at eradicating the sexual relations of the supposedly ordinary prisoner, the small army of doctors, psychiatrists, and psychologists who descended on Sing Sing in 1915 and 1916 were chiefly concerned with the group of prisoners Osborne had described as degenerate.

The new penologists’ effort to conscript psychiatry and psychology into prison reform was complemented by the reformers’ enhancement of general medical facilities at Sing Sing in 1915 and 1916. In February 1915, the New York State Department of Health inspected Sing Sing and recommended that a separate ward be set up for patients suffering from sexually transmitted disease (STD). This recommendation was seconded a few months later by two state investigators who suggested that Sing Sing open a new hospital in which “psychopaths,” STD patients, and convicts suffering from contagious diseases would be held separately from prisoners in the general wards. Those suffering from infectious diseases other than STDs would be labeled “normal,” while “psychopaths” and STD patients should be held in a ward for “special” cases. The investigators further recommended that a psychiatric study of prisoners be undertaken in which all new admissions to the prison would be thoroughly studied according to a case method, with special attention paid to those with mental and nervous disorders, “sexual perversions,” suicidal tendencies, and records of multiple convictions. The 1915 plans for a psychomedical facility at Sing Sing proposed a double innovation of the established prison system: The psychic lives of prisoners would be added to the fields of scrutiny, and the past and present sexual practices (and desires) of convicts would be read as signs of a peculiar psychic type (the psychopath), who, in turn, would be incarcerated in separate facilities.

The following year at Sing Sing, Dr. Thomas W. Salmon, of the National Committee for Mental Hygiene, and Dr. Bernard Glueck, a psychiatrist who had recently instituted nonverbal intelligence testing of immigrants at Ellis Island, set up the country’s first penal psychiatric clinic. Funded by a sizable grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, the clinic proceeded under Dr. Glueck’s directorship to examine virtually all of the 683 prisoners committed to Sing Sing between August 1916 and April 1917. Glueck’s dense, seventy-page report on his findings was published to much acclaim in 1917; it was the first comprehensive psychiatric case study of adult convicts in the United States. Like the Health Department investigators, Glueck conceived of his studies as just one element in the much larger effort to develop “rational administration” in imprisonment. He and his clinicians proceeded to interview every incoming convict about his family background, sexual practices, health, education, and employment history; they then conducted a series of psychological tests for “mental age” and dexterity, and administered psychiatric tests of the prisoner’s emotional state. On the basis of this information Glueck divided all the incoming prisoners into three groups: the intellectually defective (those with low “mental ages”); the mentally diseased (those who suffered from hallucinations and delusions); and the psychopathic, whom he described as the most difficult to define and the most baffling. He concluded that almost six out of every ten of the incoming convicts were either intellectually defective, mentally diseased, or psychopathic.

Glueck’s study of Sing Sing convicts was one of the first to theorize the existence of “psychopath criminals,” and his work became foundational both in studies of criminality and homosexuality. According to Glueck, approximately one in five of the incoming prisoners was a psychopath. It was to this category that those prisoners with a history of homosexual relations were most commonly consigned. As Glueck put it, the classification of psychopathic was a judgment of the prisoner’s entire way of life, not just the crime he had committed; sexual habits were one of four determining fields of enquiry (the others were the family’s medical history and the convict’s employment and education history). From the beginning, then, scrutiny of prisoners’ sexual relations – and homosexual relations in particular – was critical in the study of psychopathology among prisoners. He wrote that, “in contemplating the life histories of these (native-born psychopaths), one is struck very forcibly with the unusual lack of all conception of sex morality.” A wide range of sexual activities, and not simply sex between men, was read as psychopathological. He described one in three psychopathic prisoners to be “markedly promiscuous,” and nine percent as polymorphously perverse: He was perplexed to find that many individuals who had had “repeated” sexual relations with other men had been equally sexually active with women, and concluded simply that these convicts were not “biologically sexually inverted.” They were, however, as psychopathological as “biological inverts.”

....

As well as striving to discover, prevent, and punish sexual relations between convicts in the model progressive prison, the new penologists attempted to change relations between black prisoners and white prisoners. Unlike the matter of sex, neither the “race question” nor the prison’s small minority of black prisoners were objects of sustained discourse among Sing Sing’s reformers at this time. Nonetheless, race ideology deeply influenced and was, in turn, influenced by, the new penological program of reform. At Sing Sing (and at Auburn) the new penologists set about classifying and more formally segregating prisoners on the basis of the “one-drop” criterion of American race ideology. The new penologists conceived of their task primarily as one of assimilating prisoners born in Europe and native-born Americans classified as “white” to an ideal, manly citizenship. Programs that were designed to socialize prisoners as citizens were implicitly aimed at white native-born Americans and European immigrants; certainly, no resources were specifically earmarked for the education or postrelease employment of black prisoners. Many of the educational programs were specifically aimed at Italian, Polish, and German immigrants, with the objective of socializing them to be good Americans. Classes were started in English literacy and civics (the one at Auburn was known as the “Americanization” class) for white prisoners, and on at least one occasion, a large business enterprise sent an Italian-speaking agent to Sing Sing to train and recruit Italian convicts for postrelease employment. Besides crafting a prison program that took for granted that white convicts were the proper object of reform, the new penologists took steps to formalize and rigorously enforce the physical separation of white from black prisoners. Black prisoners were concentrated in the unskilled work companies, and white prisoners in the semi- and skilledlabor companies by day. By night, under Osborne’s direct orders, black convicts were segregated from white convicts. Early on in his wardenship, Osborne’s expressly prohibited white and black convicts to share cells with each other.

Black prisoners did not miss out entirely on the privileges and activities established under the new penologists. As a rule, privileges that were extended to white prisoners (such as membership in the leagues, participation in sports, etc.) were generally extended to black prisoners, too, suggesting that the new penologists considered black prisoners capable of participating in democracy and civil society. But, as had been the case at Auburn, these privileges were always extended in such a way that they would not undermine the segregation of white from black, nor, more critically, raise a black prisoner above a white prisoner. Indeed, new penological reform in general seems to have formalized race segregation and, not incidentally, widened racial inequality, at Sing Sing.

- Rebecca M. McLennan, The Crisis of Imprisonment: Protest, Politics, and the Making of the American Penal State, 1776-1941. Cambridge University Press, 2008. McCormick, p. 397-402, 404.

Image is Warden T. M. Osborne, Sing Sing, centre, surrounded by Sing Sing prisoners. c. 1915-1916. Bain News Service glass negative. Library of Congress. LC-B2- 3310-7.

#sing sing prison#penal reform#progressive penology#thomas mott osborne#prison discipline#penal reformers#prison administration#crisis of imprisonment#new york prisons#classification and segregation#wolves and punks#history of homosexuality#history of heteronormativity#sex in prison#racism in america#african americans#racial segregation#history of crime and punishment#academic quote#reading 2023#psychiatric examination#psychiatric power#prison psychiatry#criminal psyc#criminal psychology

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

wish there were more ndn creole blogs on here, it’s all recipes and history pages, like we’re still around and being a creole ndn is way different to a non creole ndn experience, I know we’re around cause I met one a few weeks ago irl just by chance, but everyone acts like we’re either only in Louisiana and not worth acknowledging or just gone altogether.

#lousiana creole#Pls we have really interesting history#Ppl only talk about us when they want to prove something#It’s true most creoles r in Louisiana but clearly not all of us#Also ppl only ever consider creoles and cajuns as literally black and white#Cajuns are a subset creoles and cajuns are also often mixed. Like around 40% of all Cajuns are ndn.#Creoles can be mostly native creoles can be mostly white Cajuns can be mostly black#Most of us r all a lil mixed but it’s not as simple as everyone else makes it out to be#Issa whole culture and ethnic group that deserves recognition#Like my family left Louisiana we’re cut off from everyone else bc of family drama we live far away but we still keep our culture close#Or at least my grandpa did but you still see it echoing#idk sorry i’m just rambling now#But we used to be huge before Louisiana became America#American White supremacy fucked us over and our language and culture were all attempted to be wiped out#They forcefully segregated us that’s why now Cajuns are considered white Creoles are consider mixed or black#Makes me sad to see ppl treating us like we’re gone when we’re not

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

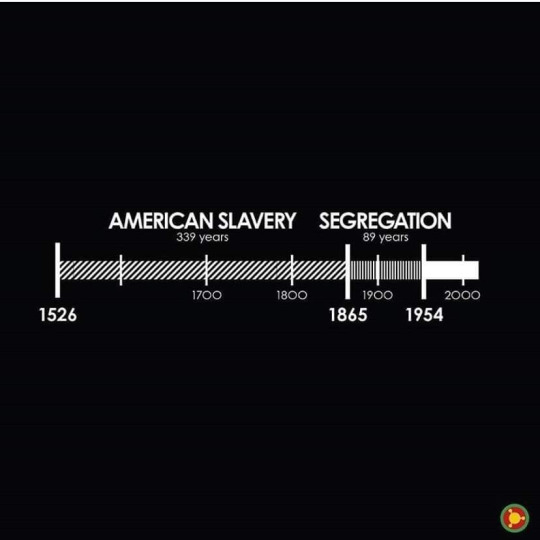

A Timeline Of Racism In America

1 note

·

View note

Video

👁👄👁

#video#tiktok#tiktoks#funny#lmao#wtf#usa#united states#united states of america#rubik's cube#segregation#officialqueensimba

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

When, exactly?!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Even though African Americans paid taxes for public libraries, they weren’t allowed to use them,” said Mike Selby, a librarian at Cranbrook Public Library in British Columbia and author of “Freedom Libraries: The Untold Story of Libraries for African Americans in the South.” “There were segregated libraries for African Americans, but they were usually shacks with unusable castoffs and no staff. … These freedom libraries, some of them were the first contact these families had with books.”

~ Freedom Libraries: The Untold Story of Libraries for African Americans in the South author Mike Selby (@AuthorSelby) from the Washington Post

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Today, I am learning about Malcolm X, and the way he talks about white liberals really struck a chord with me.

youtube

I also found this quote from him about John Brown, a white abolitionist who went to war for his beliefs and helped push America towards civil war. I only learned about John Brown from my very racist AP US History teacher, Mr. Green, of Hampton Township, at Hampton High School, in D Hall, who lied to us and said the Civil War wasn't about slavery. And so this'll shock you, but I never learned about Malcolm X in school! Anyway, Malcolm X says:

“We need allies who are going to help us achieve a victory, not allies who are going to tell us to be nonviolent. If a white man wants to be your ally, what does he think of John Brown? You know what John Brown did? He went to war. He was a white man who went to war against white people to help free slaves. He wasn’t nonviolent. White people call John Brown a nut. Go read the history, go read what all of them say about John Brown. They’re trying to make it look like he was a nut, a fanatic. They made a movie on it, I saw a movie on the screen one night. Why, I would be afraid to get near John Brown if I go by what other white folks say about him.

But they depict him in this image because he was willing to shed blood to free the slaves. And any white man who is ready and willing to shed blood for your freedom—in the sight of other whites, he’s nuts. As long as he wants to come up with some nonviolent action, they go for that, if he’s liberal, a nonviolent liberal, a love-everybody liberal. But when it comes time for making the same kind of contribution for your and my freedom that was necessary for them to make for their own freedom, they back out of the situation. So, when you want to know good white folks in history where black people are concerned, go read the history of John Brown. That was what I call a white liberal. But those other kind, they are questionable.

So if we need white allies in this country, we don’t need those kind who compromise. We don’t need those kind who encourage us to be polite, responsible, you know. We don’t need those kind who give us that kind of advice. We don’t need those kind who tell us how to be patient. No, if we want some white allies, we need the kind that John Brown was, or we don’t need you. And the only way to get those kind is to turn in a new direction.”

#original#malcolm x#john brown#racism#anti-racism#allyship#civil rights#american civil rights movement#my schooling left out a LOT of stuff that seemed to be left out for no other reason than it would make us confront modern racism#i went to a school that was like 99% white and the other 1% was Asian i didn't have a full conversation with a Black person until I#was already in high school. it was fucking bad and that system produced a LOT of racists i mean a LOT#i had to unlearn a lot of things in order to try and become the kind of white person that doesn't suck for people of color to be around#we were never taught outright that Black folk are inferior but we were instead taught that racism is over and we needn't worry about it.#aka we were taught that any incidences of modern racism were essentially harmless and exaggerated. which is so deeply evil and insidious.#and NO ONE EVER EXPLAINED WHY OUR ENTIRE TOWNSHIP HAD NO BLACK PEOPLE - IT WAS WEIRD HOW NO ONE TALKED ABOUT IT. FUCK SUBURBIA MAN!#You don't have to tell a white person racist beliefs to make them more racist. We'll pick those up from our segregated environments.#No no you'll have much much more success by telling him that his apathy and his aggressive dismissal of racial issues is valid.#ALL YOU HAVE TO DO is place a child in an all-white environment in America... and change nothing.#WE HAD KIDS WITH CONFEDERATE FLAGS ON THEIR TRUCKS. IT WAS FUCKING ///PENNSYLVANIA/// - WE WERE IN THE UNION. Y'ALL.#and now that kid's probably a cop if i had to guess#anyway fuck racism and fuck you mr. green and i am gonna do a lot of reading on malcolm x on my fucking own i guess#edit: *All you have to do is place a white child nearly ANYWHERE in America and change nothing.#If you're white and not teaching your kids anti-racism then you have failed them and you have failed the people of color in this country#also why tHE FUCK would you put your child in an all-white school i mean test scores be DAMNED who DOES that?!

4 notes

·

View notes