#and deconstructing and reconstructing narrative and characterization

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

when you draw something just for self indulgence but then go too hard on it and get mad that you made it too cringe to share. this sideblog was an attempt to not care about that and draw things without worry but apparently there is no limit to what my brain is embarrassed about

#tbh? less about the drawings and more like.. i’m afraid to share my visions of the characters i have LOL#bc they are my own and not canon. and i don’t want people to think i’m wildly misunderstanding the character#bc i more than understand and am also invested in the boundaries of canon. but i also like doing what i want#and deconstructing and reconstructing narrative and characterization#and i feel like people won’t know that but i also feel so silly putting a disclaimer over everything i draw of being like#‘oh this is my own thing actually’ LOL#anyways. long winded ramble over how i drew that princess mononoke scene with my vers of silver/gold but im too much of a coward to share#rambles

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

I know dc has sort of already tried this a few times, but if you were to create an Ultimate Universe (the early 00s one) style interpretation of the DC universe, which characters would you deconstruct (like hulk or hank pym) and which would you reconstruct (like spider-man)?

I'm not sure who, if anyone, I'd take to the woodshed in the way they did Bruce and Hank. But in a more positive direction, I think Ultimate Superman writes itself.

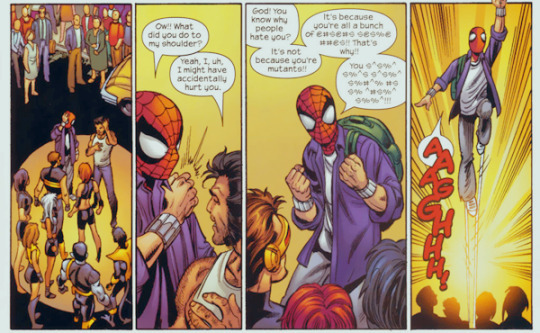

One thing that the Original Ultimate Universe caught basically infinite shit for was that Spider-Man was the only likeable hero out of the entire roster- everyone else was a jingoistic government stooge, a sellout, an ineffective moron, a vindictive moron, or involved in whatever label you want to stick on the clusterfuck that was the Ultimate X-Men. Certain commentators treated this as something that happened by accident- like somehow Spider-Man was the only character to slip through a net- but this was actually a very deliberate thematic and political choice. The early Ultimate Universe in particular was undergirded by a running theme of the ways in which the heroes were compromised and made dirty by having to exist in a world that was remotely politically realistic. Captain America was unexamined in his patriotism in the way that a guy unpaused direct from the end of world war 2 would realistically be; likewise the celebrity and proximity to power of the classic Avengers lineup was characterized as insidious and complicit in the crimes of the Bush Administration even as they embark on flashier superheroic exploits. The Fantastic Four's dimension-trotting adventures were explicitly underwritten by their work building new ways for the Military to kill people in the Middle East (paraphrasing a direct quote.) The X-Men were a hotbed of moral compromise, seediness and occasional bouts of ethically-dubious psychic-assisted ass-covering, with the repeated drumbeat from multiple writers that they were letting their own narrative about being feared and hated overwrite their awareness of how their entire enterprise was a complete circus- itself a metatextual commentary on the out-of-universe observation on the fact that, for all they bloviate about being oppressed, a significant chunk of their lineup consists of cishet white people with supermodel good looks:

As shown here, a consequence of all this is that Spider-Man, despite not changing much in his characterization from Baseline Peter, came out looking like a paragon. His early-career anger and sense of put-upon-ness is significantly more justified in this continuity because the entire world actually is out to get him; he got his powers through gross negligence by a military industrial complex contractor, he spends his time constantly beating the crap out of more of their runoff, and American Intelligence is circling him like a hawk waiting for an opportunity to headhunt him and sicc him on their enemies. Bendis narratively tied this to his youth; he's able to be a hero in the classic mold because the world hasn't dragged him down yet. The forces arrayed against him, of which there are many, haven't found a way to pin him down and make him sell out. Everybody is expecting him to sell out. Kingpin has a whole speech about it; Jameson's hatred of him is expressly tied to the fact that he lives in a world where skepticism of good intentions is generally pretty justified. But Peter remains, fundamentally, an outsider- in a way that feels contrived in mainline Marvel but incredibly well-earned in this context- right up until the forces aligned against him actually do get him killed. Accounting for comic book time, poor bastard only lasted a couple years before the bottom fell out and his lifestyle caught up with him. Only the good die young.

So. Superman. The parallels here are obvious, right? Superman, like Spider-Man, wants to do classic Superhero Shit. He's not overtly political and he isn't ambitious. He wants to go out and save people, he wants to stop people who're trying to hurt people from hurting people. He's the nicest guy in the world and he can eat guns and it's almost impossible to make him do something he thinks is the wrong thing to do. But if you live in a world remotely like ours, having that level of power and using it to go out and help people and save people means that you fall somewhere on the scale between weirdo and enemy of the state, and the bad guys you have to stop from hurting people work for the duly elected government, or they run the economy, and the guns you have to eat belong to the cops and the military as often as they do bank robbers in white striped shirts. Putting a nice guy who wants to do the right thing into a setting with a remotely appropriately cynical outlook on politics is basically an instant deconstruction without you having to do anything extra to the hero himself, it's like throwing a sodium bomb into a bathtub.

youtube

This sequence from Batman vs Superman is one of my favorite pieces of superhero media that exists, and any Ultimate-style spin on the character would be extrapolated directly from this. The Snyder take gets some flak for taking itself too seriously, being too dark, yadda yadda yadda, but Superman himself is very pointedly not the site of any of that darkness. Superman is just Superman. He spends this whole sequence doing Classic Superman Shit- no violence whatsoever, just rescues- and the talking heads won't stop picking him apart, looking for the angle, looking for the catch, looking for a lever to get him under control. Tyson trying to make him into some kind of existential harbinger of Man's insignificance in the universe, juxtaposed against a mother in a flood zone crying tears of joy because God didn't send boats or a helicopter but spraypainting Superman's logo on the roof actually paid off. Lex wants him dead in this version mainly because a guy this powerful being this nice makes him insecure.

What really sells this for me is that Clark is visibly aware of, and deeply uncomfortable with, the immense impact he's having on everyone- he's asking all the same questions about the implications of his own existence as the talking heads. He doesn't know either! But there are still people in burning buildings and flood zones. Someone's gotta do something, and he's someone, and he can do anything. And he is, of course, dead by the end of the movie.

#my umbrage with the film is measured and aimed elsewhere#there are ways in which IIRC the film is trying to have its cake and eat it to IRGT the military and platonic hollywood terrorism#that signifies while saying nothing yadda yadda#but on the whole they had a much stronger sense of what they were going for than many will admit at gunpoint#thoughts#meta#ultimate marvel#batman vs superman#superman#spider-man#marvel#ask#asks

141 notes

·

View notes

Note

i have had like 10 friends rec worm to me but nobody’s given me a good like, gist of its vibe and what its abt because ‘its best blind’, could u please give a like brief summary and vibe check of it 😭 it’s so long i dont wanna try and invest that much time without knowing much abt it

so, worm is a 1.7 million word long webserial written in 2010. 1.7 million words seems like a lot, but it was also written over a relatively short period of time, which means the writing style is very easy to parse--the ideas aren't without complexity, but the language itself isn't intimidatingly dense. you can get through it at a very decent pace. i agree with your friends that there are vast portions of worm that hit best when you're unspoiled, but the thing is that worm is long enough that giving you the basic plot pitch is in no way spoilers for any of the things that i wouldn't want to see spoiled for someone. i'm actually kind of baffled they're not telling you Any Thing, because it is in my estimation one of the best books i've ever read, but it also Needs a briefing before you get into it for like five different reasons. which i will now provide. i swear to god this is brief by my standards it's just that i am very thorough

worm is a story about superheroes and supervillains, set in a world where superpowers are traumagenic--rather than appearing randomly or innately, some people gain powers after a traumatizing event happens to them. the protagonist is taylor hebert, a 15yo girl who has the power to control insects and desperately wants to be a superhero. and then accidentally finds herself scouted by a team of teenage villains instead. who's to say how she's going to react to all that!

one of the most compelling things about worm is that the superpowers in it serve as visceral, hyper-literal metaphors for the trauma and traumatized coping mechanisms of the characters with those powers. each power is incredibly specific and thematically relevant to the person who has it, and it's incredibly interesting and evocative. it feels so natural and well-done that it comes off like how superpowers are just meant to be written.

the fact that superpowers stem from trauma also means that worm is fundamentally a narrative about trauma. specifically, about traumatized teenagers and the relationships they form as they cling together while struggling through growing up traumatized & mutually coping with an increasingly intriguing, intense, and far-reaching escalating plot. worm's depictions of trauma + mental illness--including unpalatable trauma responses, including traumatized characters who are allowed to be complicated and nuanced and messy while still receiving narrative respect--are deeply real-feeling and impactful, and they're placed in the context of a well-spun + engaging story.

i really do have to stress how excellent the character writing is. worm is fully deserving of being as long as it is. over the course of 1.7 million words of character development, the average reader's reaction to the main characters goes from "sorta interesting" to "okay, i want to see where this goes" to "augh...really likable" to "i am now on hands and knees crying and these characters are going to stick around in my brain forever." wildbow has incredible talent for efficiently conveying complicated, real-feeling, and viscerally evocative characterization. many of the interlude chapters (chapters written from the perspective of different characters other than taylor) are so interesting, fleshed-out, and emotionally affecting that they make you wish you could read an entire novel about just the side character being featured. with that level of characterization for just the side cast, it's not surprising that taylor (& co) are genuinely just downright iconic. and i do not say that lightly--taylor is truly one of the best-written protagonists i've seen in anything. ever.

the other main pitch-point for worm is that it's a fascinating deconstruction/reconstruction/examination of the conceits of the superhero genre. it answers the question of--what would the world have to be like, for people with superpowers to act the way they do in classic cape media? and it does this well enough that it's interesting even if you have only a passing familiarity with cape media. i am not a big superhero media fan, but worm addresses virtually every aspect of cape media that was under the sun around 2010 in a way that's so interesting i still find it incredibly engaging. the approach it takes makes the narrative very accessible even to people who aren't usually cape media fans.

and speaking of the narrative: the end of the story is coherent and satisfying and deeply thematically resonant*. the way worm follows through on all of its main mysteries & plot threads is excellent. you don't have to worry about getting thru 1.7 million words and being dissatisfied by the author shitting the bed at the end, or anything like that. he does an amazing job of weaving together plot events in a way that makes each successive one feel rationally, thematically, and emotionally connected to what came before. there's really only one part where i feel the story stumbles a bit, but i think it was the best option he had for the narrative, and it's by no means a dealbreaker. it's in fact really impressive how cohesive and satisfying worm is for such a long webserial released over such a brief period of time.

*this is subjective ive seen some people who didnt love it but ive never seen anyone who downright Hated it who didnt also demonstrate egregious misunderstanding of literally everything worm is about. so thats a good sign

as for the downsides of worm/things that might put you off:

there is a very long list of trigger warnings for it. if you have any trigger warnings you want you should ask your friends to let you know about the relevant parts, because the fact that it's About Trauma (& about typical cape media circumstances presented very seriously) means that traumatic and violent things & their realistic aftermath are constantly happening and/or being discussed. i would not classify worm as needlessly dark or spiteful to the audience by any means, but it is intense and covers a lot of heavy topics. i do assume if your friends are all recommending it to you, they think none of the material would be too much for you, though!

worm was written in 2010 by a white cishet guy from canada. it's typical levels of 2010-era bigoted, it has a deeply lesbophobic stereotype character, it has some atrociously racist stereotype characters, the author really hates addicts, It's Got Blind Spots. i think worm is generally fully worth reading despite these, but very fair warning that it can get bad. i think what exacerbates this is that worm is generally extremely nuanced & sympathetic regarding ideas such as "crime is a result of systematic circumstance vs people just being inherently evil" and "mentally ill people who are traumatized in unpalatable ways are still deserving of fundamental respect as human beings" and so on and so forth, so it's extra noticeable and insufferable when you get to a topic the author has unexamined biases on and all that nuance drops out. the worst part is that a lot of this is most concentrated in the early arcs, so you have to get through them without being super attached to any of the characters yet. it is worth it though.

worm like. Does have a central straight relationship in it. and it's a very well written straight relationship for the most part and i like it quite a lot. but worm also passes the bechdel test with such flying colors that it enters 'unintentionally homoerotic' territory. which means a lot of people were shipping the main character ms taylor hebert with her female friends while the story was being released. which caused the author to get so mad he 1. posted a word of god to a forum loudly insisting that all of the girls are straight and 2. inserted a few deeply awkward and obvious and out of character scenes where he finds an excuse for the girls to more or less turn to the camera and go "i'm not gay, btw. this is platonic." This is fucking insufferable, and will piss you off immensely, but then you will get to any of the number of deeply emotionally affecting scenes between them, and at that point you will be too busy sniffling piteously and perhaps crytyping an analysis post on tumblr to be mad about all that other shit. also they're only a couple tiny portions out of an entire overall fantastic novel

overall: if those points don't sound like dealbreakers (i hope they aren't they're really massively outstripped by the amount of devastatingly good moments in worm, worm still has a thriving fandom over a decade later for a reason), you should absolutely give it a shot and see what you think. my final note is that you have to read up until the end of arc 8 to really see where what makes worm Worm kicks in, so aim for at least there to see how you feel about it if you're just thinking about dipping your toes in vs fully committing. i hope that was helpful and not too long :)

oh and don't go in the comments section on wordpress if you don't want spoilers. or anywhere else in the fandom at all. you will be spoiled. quite possibly for things you could not even have imagined were topics to be spoiled on.

#ask#wormblr#parahumans#ill tag it to save it so i can reference later. and maybe other people will find it helpful

364 notes

·

View notes

Note

i'm so curious if you have anything specific you would like to say about your processes regarding mirroring different bsd character's mannerisms and methods of speaking, because 👀 (-> person who recently picked up writing bsd fic but struggles wrt matching character voice as a rule). completely fair if it's something that you either have said all you intend to about for rn or if it's something you would prefer to engage with only in more direct conversation though!!

oh, all i ever want to do is talk about writing as a craft; i'm delighted to chat about it.

much of what I do for bsd is the same as I do for characters in other fics. I'm never aiming to necessarily mirror the characters as they appear in the source materials, because I write fanfiction to explore the characters outside of the confines of canon. instead, I aim to recreate the "look and feel" of the characters, so they still feel like themselves, even when adapted to my authorial voice and lenses of interpretation.

There are a several principles of canonical interpretation that I use to guide my characterizations, which I've listed below.

Characters are storytelling devices that serve the canonical narrative's key themes. Even if I'm writing outside of canon, I'm not going to be able to make them feel like themselves without first understanding canon (genre, themes, tone, thesis, etc.) and the characters' roles in the context of canon.

Characters are comprised of component parts (such as goals, motivations, flaws, experiences, preferences, skills) that, if conflated, obscure or make it very easy to misidentify their behavioral patterns.

Characters are designed and written intentionally. There is no random detail; every scrap of canonical information survived multiple drafts, rounds of revisions, and editorial scrutiny for a reason.

If I don't understand why a character behaved the way they did, or if the "why" seems out of character or incongruent with the overarching narrative and themes of the story, then I assume I'm missing details; I have misunderstood some aspect of either the character or the context; my bias or experiences are clouding my perspective; or I am operating from a false premise or place of ignorance. This is especially important for engaging with works outside my own cultural context, and for cultivating discernment, emotional intelligence, sincerity, compassion, and curiosity (which are core to my values).

I continue to deconstruct and reconstruct and reconcile characters and their narratives, constantly testing the patterns I've previously identified against new information or canonical material, and refining or reworking them accordingly. In other words, I remain flexible in my interpretations, and I continue applying those interpretations to ongoing canon. I don't want canon to validate my interpretations, I want to understand canon.

To write characters that feel like distinct, whole people, I observe people, myself and others, both granularly and holistically, with insatiable curiosity. Otherwise I risk writing my own ego, patterns, and mannerisms over and over. That doesn't work for me, because I write and read to explore the expansiveness of existence, not to force existence to fit into the narrowness of my present perception.

You only asked about characters' mannerisms and methods of speaking, so many of the above principles may seem out of scope. They're not. If you only observe patterns without analyzing their causes and context, you'll, at best, only ever be able to caricature them, but never replicate, adapt, or expound upon them.

But, with the above principles in mind, my process for learning to write characters' manner of speaking includes revisiting their canonical dialogue to identify their (1) speech patterns like vocal rhythm, pace, intonation, and pausing (sources of which may vary based on the medium, e.g., narrative descriptions and punctuation for written canon; expressions and other characters' reactions for visual canon; etc.); (2) vocabulary, dialect, frequently used phrases, favorite filler words; (3) nonverbal modes of communication (e.g., Chuuya screeches like a vixen in heat when he's either in Corruption or really, really, really riled up by or in regard to Dazai).

Then, I note variations in (1)-(3) across interactions with other characters and in different settings, noting where, how, and potentially why those changes occur (e.g., Kunikida doesn't usually use honorifics, but he does for Ranpo and Fukuzawa; it's explicitly because he immensely respects them and desires to learn from them, the former perhaps because of the latter).

For Japanese speaking characters, I research which type of keigo they use in canon, and which particles of speech indicating tone they commonly use, and why/when/to whom they code switch. I don't speak Japanese, so I generally rely on analyses provided by native speakers, but I also listen/read the raws to confirm the formality or type of keigo they're using in situations relevant to whatever I'm writing. For other languages and dialects too, the process is roughly the same; I look for resources from native speakers and translators that provide insight into patterns I wouldn't otherwise hear or recognize as a monolingual English speaker. I don't do this with any intent to try and replicate them, but to better and more precisely adapt the character's speech patterns to the English version of them. For example, I've noticed a lot of MDZS/Untamed fanfiction writes Lan Wangji speaking very brusquely. This is because he does so in Chinese. But in Chinese syntax, his short sentences indicate his formality and noble character. In English, which requires packing way more context into sentences than Chinese, short sentences with minimal context can come across as informal, clipped, and sometimes rude/dismissive/abrupt.

There's also the matter of code switching, which transcends any one language, and lends lots of insight into our relationships and dynamics. We do not usually talk to our best friends the way we speak to strangers, for example. Our accents and dialects also shift with our settings; I'm from the Deep South, you call EVERYONE "ma'am" or "sir" if they are even slightly older than you or you otherwise respect them; using "ma'am" or "sir" where I currently live is liable to offend someone. Paying attention to this in characters can really, really help you capture them across contexts. It's also just generally respectful to engage with the cultural and linguistic context of the stories you love.

For their body language, it's very similar to the above, in that I revisit canon, note patterns, and compare contexts. (Also still salient are my notes about culturally specific details and code switching -- body language, like any form of communication, is also informed by our upbringing and cultural backgrounds.)

Then, I write, revisiting my notes and canon as necessary, but mostly focused on drafting. During revisions, I more carefully compare my dialogue and body language against canon, and pay closer attention to refining my dialogue to sound more like the character. Sometimes I watch or read relevant canon before writing specific dialogue so that the rhythms are fresh in my mind.

I'm never trying to erode my own authorial voice, and I make all sorts of choices with how I adapt character voices to my writing style and preferences. But, I can do that without compromising the character's "look and feel" because I've done the above work to understand the essential elements of their communication, and how those elements relate to their overall characterization (essential to which is applying the principles I listed at the outset to the speech and body language patterns I notice).

But, like, all of this amounts to just revisiting canon a lot and connecting patterns in the characters' speech and body language with their characterization + being curious about the cultural layers you may be missing.

Also, with regard to bsd, I recommend reading, even if just in snippets, works by the irl!authors, since Asagiri almost literally quotes them sometimes, and certainly uses the irl namesakes' authorial voices to guide the tone, inflections, and speech quirks of the characters he writes. (I love, love, love to invoke irl!Chuuya's symbolist and sometimes bewildering habit of mashing together imagery and bastardizing words/turns of phrase in ways that are nonsensical when taken literally, but which are evocative or meaningful in the tone, atmosphere, and meter of his poetry. I'm not as clever as him, so I'm silly with it, but nevertheless, it sparks joy.)

I have no idea if any of this is helpful, but it's how I enjoy approaching it. I'm also inclined to think it works for me; the element in my fics I'm complimented on the most in comments and feedback tends to be my characterizations.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

i defeated Everhood

undertale... 2! [spoilers]

ill start with the non-plot stuff, i really like the look of the game. a lot of effort went into making all the characters feel distinct and likeable. knight lost-a-lot has an australian accent, and im not saying that because he called me a sheila or whatever, its just something that i think fits the character. yknow youve made a good character when you can imagine stuff like that, yknow? and the environments are all memorable too, even with places that risk being samey like the nightclub and the carnival

and the writing's a lot of fun too! so, i feel like were all on the same page of saying its hard for media to take itself seriously nowadays. serious emotion has to be undercut with a whedonesque quip, that kinda thing. Everhood knows what its doing; it knows when to tell a joke and it knows when to stand back and let a scene emote. it does this without feeling like its two segregated games, in my opinion. like, even after *that moment* where things get serious, theres still levity, and theres still serious character moments before that too.

and the gameplay is great too! yknow that thing where you look out the window of a car and you imagine a ninja or something running on the rooftops? its kinda like that, but youre imaging a little guy jumping between the notes in a rhythm game. thats such a fun gameplay gimmick

so, a lot gets posted about "quirky earthbound-inspired rpgs (which may or may not be about depression)". i always thought that its was kinda stupid, because people can only ever name omori if you ask them for examples. and thats not even to say that theres a drought, no theres tons of em! Jimmy and the Pulsating Mass, Knuckle Sandwich, Heartbound, Oddity, the LISA trilogy... oh, and obviously Undertale. all of those seem like direct reactions, but none of them (to my knowledge) seem like call-and-response answers that directly build on their inspirations like how Undertale subverts traditional rpg game mechanics...

except everhood. if undertale is about building and examining a world with plot-important 4th wall breaking where rpg mechanics are deconstructed, everhood painstakingly reconstructs them. this isnt to say that its not post-modern, quite the opposite. it intentionally builds a world that has the same post-modern sensibilities, where the rpg mechanics are welcomed entirely

this is your last call for spoilers. if youre an Undertale fan, or just a fan of the narrative analysis of traditional game mechanics, you need to play this game

for example, Undertale makes a point of emphasizing to the player that the monsters arent just disposable enemies, theyre people who deserve to live. Everhood does the inverse: everyone is an immortal going insane, and they deserve to be put out of their misery. this still humanizes and makes you sympathize with the encounters without removing the violent conflict. instead of everyone deserving to live, everyone deserves to die, but not in a no-mercy style "im a monster because im bored" way. honestly, i think Everhood improves on this from Undertale. everyone has an overworld sprite, they all reoccur in multiple locations, and theres only one of them. its hard to feel a connection to just another vulkin or just another woshua; here even characters like the goth store clerk form more of a connection through repetition.

another thing i like is the silent protagonist. Undertale characterizes Frisk as a reveal, telling you that you the player are not this character just because youre controlling them. enforcing your will over the narrative is a bad thing: that means youre retroactively making chara evil. in Everhood, the player controlling the character is diegetic, and entirely welcomed.

basically, Undertale was designed with the notion "lets make a game where the player treating it like a normal rpg (the player is the main character, killing is good) is unwelcome and unfulfilling by subverting normal tropes" to which Everhood answers "okay, now lets build a world with the same level of subversion, but playing it like a normal rpg (the player is the main character, killing is good) is VERY welcome and fulfilling".

so yeah, wonderful game, totally recommend it. if i had to pick one thing it does best, i gotta go with the narrative resonance, but the characters are a close second. green mage is such a cool dude.

closing this out, the sequel has been announced and theres a trailer out. i have... no idea how theyre going to continue the narrative. i figured the buddhist imagery was hinting at reincarnation so the new game+ was diegetic too... my guess is that either theyre gonna do something narratively disconnected but with evolved gameplay like how final fantasy works, or its basically gonna be like... a different everhood. as in the place. looks killer either way

1 note

·

View note

Text

No, more generally WHAT THE FUCK THEY ARE PLANNING WITH THEIR FANTASY UNIVERSE

Because I say you: they are destroying it.

They started with LoK, creating all those Retcons and incoherences in characterization of the characters and plot that everyone with a working brain sees.

But everyone refuses to see It, because "Look, is modern now, Who cares if It is exagerated as progress and without the elements of the show, but a simple reconstruction of USA", "Look, the Korrasami, Who cares if Asami never had a real characterization and their relationship was forced like Makorra", and goes away, refusing to see the bad flaws and the seeds of destruction, like the Total inexistance of complex characterization, the lack of Real Adventures, and how all the Good things of the original show were cancelled.

And that because they wanted their Perfect Sci-Fi Show of their original plan!

Because the problem with Azula isn't the worst, o no.

The most damned thing in this comic, no in the majority of these comics, is that they are all boring! All things that could be Adventurous, Exotica, Fascinating and Fantasy are destroyed, all reduced to American Comedy and Super-Heroes' Tales! A lot of good ideas, but all simplified and understood under a single view: the Libertarian. Not a more Rich Presence of different Ideas like in AtlA, when socialist, liberal, distributist, even some conservative and libertarian views were present at the same time, in a dialogue when some of them found a conclusion good for everyone: It was all dominates by the view of American Libertarians Thinking! So, be progressive about you individuality, but when You're poor, probably is your fault. Social and cultural influences, imperialism? Suck them: they were simple illusions! And if you think differently, Well, your are just lies that you give to yourself and the other.

Frankly, first the Avatar Studios start a reboot of all their sources, starting with the comics and LoK, cancelling all the Retcons to the original lore, first the Studios will survive.

If they accept that they can't be te eternal mirror for two libertarians when they can masturbate about themselves thinking that they are making sex, the Avatar Studios and Avatar franchise Will survive.

But It will be problematic. And they will never do a similar thing.

We have to stop with fake deconstruction without purpose.

We have to stop with being fake progressives, Who accept everything that appear as progressive when It isn't in its substantial nature.

We have to see narrative as a way to tell stories, with some Rules.

We have to accept that Classical Literature should inspired us more than usually.

Di Martino and Konietzko made simple deconstruction After AtlA.

That's what we have. A boring spin off comic, with many incoherences and retcons of an important character.

#atla#avatar the last airbender#avatar the legend of aang#anti bryke#bryke critical#anti lok#lok critical#atla comics#atla comics critical#save avatar#save atla#stop libertarian propaganda#save lok#save this fucking franchise#save narrative#narrative#classical literature

183 notes

·

View notes

Text

i keep writing and rewriting my reaction to vincenzo because there are a lot but also i'm not certain i articulate everything i hated about the ending.

i will say that i knew no matter what that i wouldn't like the ending because murdering a character as punishment for their misdeeds is not something that appeals to me. i grew up watching kirikou et la sorcière, avatar: the last airbender, lilo and stitch, and (more recently) moana. all of these are stories that say "here is an evil character that we'll stop in a way that doesn't involve jail/murder," and the only exception i make for this is light yagami's death in death note and that's because ryuk killed him as a way to end their relationship, not as a punishment for his crimes. (and gothic lit is exempt bc they have to be resolved with murder.) so, whatever happened, regardless of how much violence the babel four did, none of their deaths would have held any emotional satisfaction for me. yet i prepared myself to be unimpressed by the finale since this is what the set up has always been: vincenzo will kill hanseok, and maybe myunghee, seunghyeok, and hanseo.

i knew this from the beginning. the narrative repeated it so often i got annoyed. there were so many close calls with vincenzo pulling a gun on hanseok that that got boring. by the time ep. 20 rolled around i was just fed up and wanted someone to die because this show had already failed me so many other times with their set ups that i wanted at least one good payoff.

lo and behold, they did end up killing the four characters i thought would die. hanseo died, and though he was my favorite character, and though i felt sad he didn't get any funeral scene or help while he was fending off his brother and that his death served as a sacrifice for vincenzo instead of literally anything else, i didn't cry or even get mad about it. he died and i felt free to stop caring about the rest of the story. yay me! i do understand the fans who hated that he was killed and that he should've survived bc abuse victims don't deserve the storyline hanseo got, but this is not a show i expected to actually care about victims. despite what it says, i knew i wouldn't get this for hanseo waaaaay back in ep 8 when they brought up the victims of that gay banker and just used it as a way for us to root against the banker. they didn't treat those victims with any respect at all and so i was already prepared for them to do it all over again. and they did and it sucks, but again for me i couldn’t get as angry as i normally would about this bc i always knew that the deaths from this show would never mean anything to me bc there was just so much of it it became meaningless.

another thing i knew that was going to let me down about this show is that it didn’t have a single “good” character for me to root for. mr. hong existed, but he was murdered early on. every other character on the show is too corrupt to be the ones i would want handling a reconstruction project for a more ethical world. yes, they made hanseo go through a redemption arc, but they didn’t let him stay did they? they focused so much on deconstruction they never cared about reconstruction. so when they got to the ending where vincenzo just leaves, chayoung and the tenants are thrown into a familiar cycle of court cases and defending their plaza from it being redeveloped, vincenzo just goes on to be a mafia boss again, and the guillotine file is back in the hands of the corrupt intelligence agency that created it on the orders of their president. the only thing that changed was babel group was destroyed bc their two ceos were murdered and the lawyers of their legal rep. were also murdered.

and yet, despite my expectations being so low they were basically non-existent, i was still disappointed. they didn't let chayoung do anything (which i knew would happen because i knew something about her characterization never felt fully fledged to me the way it did to fandom, so i wasn't surprised when they delegated her as a damsel-in-distress/love interest.), they killed myunghee the way we used to burn witches (which how fitting for a female character that is cunning and cruel), and the way they killed hanseok literally made me feel faint and nauseous (i wish this was an exaggeration; the second i saw the drill pointed at him i started feeling this way and i couldn't listen/watch his death scene because it was so brutal).

so, the ending satisfied nothing for me. if people who shipped the main characters were satisfied, whatever. i was never interested in them as a ship (i tend to ship vincenzo and chayoung with other characters), so the ending was even more disappointing bc it really held nothing that mattered to me.

i was also not a person that liked the way each character idolized vincenzo because i preferred his relationships with other characters to be filled with more tension* and the narrative just told me that the writers didn't, that vincenzo's word was what mattered, that the other character's conflicting needs were meant to be eclipsed by vincenzo's needs. so when the characters were all looking into the horizon hoping that vincenzo would some day come back (for what, i ask you?) i was just like :|

(*what do i mean by tension? i mean my favorite version of chayoung/vincenzo was the early eps when she hated him for being liked so much by her father that her flaws as a daughter were highlighted more and chayoung's own hesitancy with murder bumping up against vincenzo’s lack of hesitancy. mr. cho/vincenzo were most interesting when mr. cho wanted the guillotine file to use for his own purposes. the tenants/vincenzo were the most interesting when the tenants wanted to take the gold and vincenzo was trying to stop them. even hanseo/vincenzo was the most interesting when they had the "will you kill me? will you betray me?" tension as they worked together to get rid of hanseok. these dynamics added layers to the characters and reminded us they had their own motivations that were as equally important as vincenzo’s, but not enough of these tensions lasted past a few episodes and almost always would vincenzo's needs prevail with most of the other characters going along with his plans in the end.)

and this is all without mentioning how fandom sort of ruined a lot of the show for me, too. they took the characteristics that made the myunghee/hanseok dynamic one of my favorites and gave it to chayoung/vincenzo to the point where i was always left baffled and feeling like i was watching a different show. (a good point about the end for me is that i feel vindicated watching the scene where chayoung was basically like "i don't like your methods, vincenzo, but i needed to use them as the lesser of two evils to destroy hanseok," bc it did sort of reinforce for me my own reading of chayoung which was that she doesn't mind being corrupt and blackmailing people or scaring them into compliance, but that she was not going to get her hands covered in blood or dance over the corpses of her enemy. those traits belong to myunghee who accepts her role as a villain in a way that is as cool and collected as vincenzo. and lord, imagine what a show it would've been if the writers had made the kings chayoung/hanseok, the last ones that should ever be taken, while the queens were vincenzo/myunghee who would be the ones that would make all the moves, kill all their enemies pieces, and try to destroy one another first as the two most powerful players in the game? imagine if fandom had been able to read chayoung and myunghee accurately enough that i wouldn’t have to read post after post talking about how they needed to see myunghee brutally murdered/tortured by chayoung because they would understand chayoung’s character isn’t going to do that, posts which i hated seeing bc, as i said before, violence for violence’s sake means nothing to me? imagine if the writers cared enough about chayoung/myunghee to develop them more fully? sigh.)

i feel like i'm going nowhere with this and that i'm repeating myself a lot or not making much sense. but i'll end with this: i knew the last two episodes were going to be garbage when they all gathered at toto's restaurant post-fight in ep 19 and all they were talking about was vincenzo this and vincenzo that instead of worrying after the ones that were momentarily kidnapped/injured. like thanks show, for instead of pushing the narrative along we get a vincenzo fan club meeting and another round of "i never had anything to fight for until you came along" which is a convo we've had plenty of times before.

(footnote: i edited this on may 6, 2021 for clarity.)

#anyway i'm glad i don't have to worry about the nonsense idea of a season two#and if there is one i won't have to subject myself to it bc they killed not only my favorite character#but also the 3 others that made the show interesting#so anything of value a potential season 2 would have is already nixed#i have been set free from a drama that started out extremely promising but petered out into a series of bad tropes & nonsensical metaphors#and bc there is nothing in the final eps that interests me i don't have to scroll through the tag and subject myself#to scenes of myunghee's or hanseok's deaths which were extremely upsetting to me#now time to think about writing that one chayoung character study fic that has been swirling around in my head for a bit#and those hanseo aus i've been playing around with that make me happy just thinking about#e.e.c. watches vincenzo

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

🥐

I’ve been MIA for a while because of stress. There’s a lot going on in real life that’s needed my attention. One of my snakes passed away too. It’s been difficult cause I see my reptiles as my babies cause I can’t have kids. I spoil and try to give them a good life. I know nature is out of our hands though, but it hurt. The other crap I won’t get into detail on cause most of its adulting, but I’m getting to the good. I hope you guys have been doing okay and staying safe.

I’m planning on getting drabbles out next week. So prepare for an avalanche when I update. My heart wasn’t in my work lately, so I needed to take a step back and reassess. I’m feeling refreshed about it and I can’t wait for you to see some of the requests people have sent in.

I’ve mapped out the general plot for TLOU2 fanfic I’ve been brewing in my head. I’m taking a lot of stuff that happened in the game, but also heavily reconstructing parts of the story to fit the revenge narrative the team was trying to shoot for. For me, I personally felt the plot of the game was sloppy and could have used some fine-tuning. Granted, I am not the best writer (hell fucking no I ain’t lol) but it’s going to be a fun writing challenge to deconstruct and rebuild a canon plot and hopefully make it make more sense. I got 21 chapters plotted so far, but before I go to town I’m gonna watch the playthrough of the game again along with playing the first game so I can get characterization down. I’m nervous about writing Joel and Ellie, but we’ll see where this goes.

Plotting out more of my zombie book is going great. I’m gonna be writing the first few chapters soon.

Anyway, sorry for the rant but I figured some peeps wanted to know where the fuck I’ve been. Well, here it is.

Love you and thanks for sticking around.

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

I've been holding them up side by side for A While Now and while I don't have any coherent thesis statement there are a few things that have been bouncing around in my head other than the stuff you've already mentioned:

Magical girls and idols have been compared, conflated, and conceptually crossbred for basically as long as they've been a thing, so yeah I think it makes a lot of sense that there are strong the parallels here that I think go way beyond just PMMM and OnK.

There's some interesting parallels to be made between Ruby and Sayaka's character arcs. They both take up the role of magical girl/idol after the death of a beloved mentor/parent, and then become disillusioned after their idealism causes them to swim against the current of the system they're working within. Black Hoshigan!Ruby is the result of her hitting a VERY witchlike despair event horizon, becoming cruel, controlling, and vindictive in a twisted reflection of her previous ideals. I kind of wonder how much of Ruby's messy characterization in late OnK has to do with how difficult it is to bring a character back from that point.

Kana and Kyoko are also pretty similar in that they're smart-mouthed veterans who've lost their idealism in favor of survival? Yes this is a Ruby/Kana post now /j

The Movie Arc was like if Rebellion was bad.

Rebellion's main contribution to PMMM's story is complicating Homura and Madoka's relationship via a deep exploration of Homura's psyche in which she tries to process and understand what happened to her. Characters are brought back in new contexts and hanging relationship threads are tied together in ways that build into a grand, alarming twist that fits perfectly but wasn't in the original draft of the story.

Meanwhile the Movie arc is at least in theory focused on complicating Ai and Hikaru's relationship via a deep exploration of Ai's psyche as her children try to process and understand what happened to her. Characters are awkwardly slotted into new roles and the promise of resolving emotional threads is mostly left unfulfilled as a result, leading into a finale that fails to adapt to the direction the story has taken since.

In general the most notable contrast between the two I think is that PMMM delights in deconstructing and reconstructing its own premises, while OnK is not nearly as brave.

Because of this, Aquamarine's suicide fails to parallel Madoka's wish. It isn't a grand sacrifice that serves an important role in softening or co-opting an exploitative system, and it isn't an existential enshrinement of his values into the world, and it doesn't right a single wrong done by the idol industry, no matter how much the writing really wants to believe that it is doing those things.

I guess if I do have a thesis statement it's "I think Akane should get to go back in time and try to fix OnK's story herself," but I think instead of trying to write out a fix-it-fic on an already really long post for me I'll just leave on the observation that Walpurgisnacht is the Stage Constructing Witch, and that one of the less obvious themes of OnK is "who gets to control narratives?"

Would you say there are any narrative parallels between Kyubey and Ichigo Saitou?

Oh for SURE. Obviously they both exist in very different contexts and are approaching the topic from varying levels of abstraction and such but both OnK and PMMM are at least in part about engaging with (specifically misogynistic) systems of exploitation that turn the societally imposed expectations of women's emotional labor into a commodified resource.

Kyubey and Ichigo are both agents of their respective systems acting to further its goals and ends, not necessarily out of malice but because they see exploitation as just the done thing within the framework they operate in.

Ichigo, obviously, is a businessman and I've talked before about how interesting I find the slightly manipulative undertones in the early days of his and Ai's relationship and how disappointed I am that it's something the series seems to want to downplay/retcon these days. Either way, he was still the one managing B-Komachi and therefore, he was the one who decided to market a bunch of middle school girls as 'gachikoi' idols to grown men who were way too fucking old to be thinking of them as romantic interests.

Kyubey is even more manipulative than Ichigo at the end of the day, but more out of this obsession with raw, razor's edge efficiency that the Incubators as a whole operate with. It's not that he feels... basically anything about the girls he's exploiting, but that it's just easier to bullshit them if it gets them to agree a little faster.

On that note, both of them are also pretty obviously similar in the ways they disguise exploitation as opportunity. The big hook of the MadoMagi magical girl system, after all, is the promise of having your wish granted up front and Kyubey constantly goes out of his way to emphasize to the girls just how much they could do with the opportunity that represents. The entertainment industry in OnK is framed in much the same way - Ai lets slip a certain lack that she's wrestling with and Ichigo immediately leaps at the chance to prescribe idolhood as the cure to all her ills.

Where they differ is in their actual personhood as characters as opposed to their utilitarian function in the greater narrative. Kyubey obviously doesn't really HAVE personhood, from both a Doylist and Watsonian perspective. He's an anthropomorphized representation of the system the girls spend all of PMMM fighting against and The System does not feel any sort of way about you or anything. It just Is.

Ichigo is, at the end of the day, an actual person who can and does have feelings about the exploitation he perpetuates and - at least in theory - comes to regret his hand in it. His entire role in the story post-volume 1 is (at least when Aka lets him do anything lol) about him trying to make sense of his grief in the wake of Ai's death and the role he ultimately had in making it come to pass.

TBH, there's a lot of interesting parallels between OnK and PMMM as a whole now I'm rolling them around in my head - the tension of trying to retain your personhood and agency within a system that's rigged against you, the way said system will use your desire for agency to make you complicit in your own abuse, the discussion surrounding the way girls 'fall from grace' and become monstrous once their emotions are no longer pure and palatable enough... A lot of this is just naturally emergent from being a story about systems that cannibalize girlhood, but it's interesting all the same. It's been way too long since I've properly engaged with PMMM for me to dig into it more but if anyone is at the right cross-section of OnK and PMMM brainrot, I'd love to see if you pick up on any of these same ideas too!

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Write Who You Know

Inclement weather forced me offline earlier today, and while that made it impossible to write (among other things) it did allow for some reflection on my many, many writing projects. Specifically, why some of them are proceeding while others are stuck fast. The result was enlightening, though perhaps not encouraging:

The stories that are making no progress are all stories where I don’t actually understand the characters I’m trying to write, in any way. Because my writing style is so character driven, this is a GINORMOUS PROBLEM.

Birthright was intended to be a deconstruction / reconstruction of Harry Potter. It takes the idea of a secret society / civilization of magical people living isolated from industrialized non-magical humanity and shows how that would actually work, and how it would fall apart. I had high hopes for it, but I just could not get into the headspace of the protagonist that I had created for the setting; he’s gay, he’s adopted, his parents are loving and supportive... the only thing he and I have in common are a love of books, and that’s not enough for me to work with.

Mirror, Mirror was already collapsing under its lack of effective characterization, so much that I wanted to totally revamp it into a reverse isekai with a fantasy adventurer transported to our world to fight its monsters (cops and capitalism). The original character was a college drop out working at Dollar General thrust into the adventure of a lifetime; all outside my frame of reference. Flipping the script leaves me with a fantasy character in our modern world, and while a sorcerer / rogue multiclass burning cops alive is cathartic to write, there’s no narrative meat to sink my teeth into, so it didn’t go anywhere either.

The Bad Guys is the same problem multiplied by five. Each of the newly minted supervillains comes from a walk of life I only have a limited understanding of; Dr. Axiom and Hazmat are Physics / Engineering Majors (I majored in Mass Communications), Digital Chameleon is an actor and social engineer (I can’t even get Dollar General to hire me let alone talk my way inside a huge company to steal important documents), Gentleman Caller is a proper gentleman concerned with dress and decorum and honor (nobody could accuse me of that with a straight face) and Memento Morrie is from the Big Apple (I’m from the middle of nowhere, for better or worse) so taken all together I put together a team of characters I have NO IDEA HOW TO PORTRAY.

Consequently, these three projects are being put on indefinite hiatus, until such time as I can re-engineer the characters to something easier for me to work with. There’s a few ideas that come to mind but for now, I think it’s better that I focus my attention and effort on the stories that aren’t fighting me:

Like Clockwork is basically, after a few plot rewrites and adjustments, a novelization of an RPG campaign in a bespoke fantasy steampunk setting. The characters draw heavily from fantasy conventions, but the motivations and key personality traits of each member of the party are essentially mine: Alice’s love of steam powered technology, Dr. Spatchcock’s disgust at the medical establishment’s treatment of mental illness, Sylvia’s rebellion against her family’s restrictions, and Edgar’s desire to connect with the memory of his late grandfather. Even the antagonist’s motivation, outrage at being betrayed by people he thought he could trust, is mine. The only problems are those of narrative clarity and pacing, which will be solved in the fullness of time.

The Last Machine is a post apocalyptic story, and that already gives me considerable leeway in depicting the apocalypse; all post-apocalyptic fiction is a commentary on existing society at the time it was written anyway. More importantly, the protagonist is dealing with the same “who am I and why am I here and what the hell am I doing” existential fuckery that hounds my every waking hour, so that’s a solid foundation right there. The protagonist’s friends were already loosely based on some impulse or emotion I found relatable; kind of wish I’d been able to do that with The Bad Guys, honestly.

The Gamble is also a post apocalyptic story, one that allows me to explore a different flavor of the apocalypse. The two main characters, Eric and Lyla, are written based on my floundering for purpose after graduating from college and not being able to find a regular job, and my sense of I-can’t-believe-I-have-to-babysit-this-grown-ass-man that comes from working for my dad on the farm, respectively. The Gamble is the second part of a trilogy, and the final part, The Signal, is a “humans through alien eyes” perspective shift, which gives me more leeway in narration. Both of those stories are proceeding, if slower than I like.

After some reflection, I have deduced that my fanfic is still ongoing, it’s just that the stress and strain from the pre- and post-election politics has fucked up my focus. Frisk is one of those characters that is very easy to project on (arguably by design) and that by itself makes the characters easy to write. The small town setting is also very familiar. The Frostpunk and Deltarune fics not so much, although they are not abandoned, just stagnant. We’ll see if I can get some updates out before 2021.

My non fiction work doesn’t fall into this same characterization bottleneck, so any delays are a result of research into the appropriate topics. The Post Apocalyptic Civilization Kit is currently waiting on some detailed analyses of disaster relief / response efforts and how well they worked, and after that there will be other blanks I need to fill in, but that’s all part of the process. Same with So They Called You Mad, my facetious how-to guide on becoming a Mad Scientist, and The Super Villain’s Starter Guide, which is the same thing as applied to becoming a criminal mastermind. (The overlap between the two means progress or delays with one book also carries over to the other.)

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

I already commented on the post but

"#bc they are my own and not canon. and i don’t want people to think i’m wildly misunderstanding the character#bc i more than understand and am also invested in the boundaries of canon. but i also like doing what i want#and deconstructing and reconstructing narrative and characterization#and i feel like people won’t know that but i also feel so silly putting a disclaimer over everything i draw of being like#‘oh this is my own thing actually’ LOL"

I relate to that so hard with soooo many of my stories. Like I brought up my own version of The Boys™ but genuinely I feel this with so many of my interests. Like, Undertale most of them because it genuinely has a super deep complex story a lot of people tend to misunderstand or not care about or not get the themes, and I love talking about The Themes and How Cool The Game Is and Common Misconceptions

Then I make a fanfiction that's like. Nothing like canon even a little bit. Genuine it is sometimes the fucking opposite of the Point Of The Game and like if someone ever pointed that out to me I would shake them and go I KNOW I KNOW I CARE ABOUT IT WAY MORE THAN YOU DO LET ME EXPLAIN IN DETAIL JUST DON'T INSULT ME OVER IT I KNOW WHAT I'M DOING

YEAA U GET IT HAHA! i don’t feel that way about every series bc i like to think im pretty decent with Media Literacy and like to respect authors wishes whatnot but like.. in particular stuff that’s both extremely oversaturated to the public and/or purposefully vague enough in either character or plot so it has room for exploration (like pokemon and undertale) by its Very Nature people are gonna take it and run with it! that’s why so many of those undertale aus got crazy popular, people just like pondering the “what ifs” and i think that’s wonderful. on the other side i know how frustrating as it is to see people obviously misunderstand smth in a piece of work you hold dear but in the end i don’t think it’s very productive to be mad about esp if you don’t have Ownership over that work. for better or for worse putting things out there for an audience people will always engage with it differently and it’s fine tbh. in the end if u aren’t hurting anyone then who cares!

ON A SIDE NOTE thank u for the extremely nice tags and comments 😭😭 it’s smth that i get so easily self conscious about even if i know it doesn’t really matter but its always so kind to hear that you enjoy my stuff and can relate to my plights haha

#oh the trials and tribulations of engaging w stories in a vacuum#it’s so case by case basis and my autistic ass more than understands how personal it can feel with certain shows/series/ect.#but sometimes..people take this shit way too seriously LOL#i’m just trying not to step on anyone’s toes and do my own thing bc i’m passionate about it#asks#ask

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Princess Problem

As a part of my ongoing Disney project of analyzing archetypes and characters through history, the Wreck It Ralph 2 trailer hit me hard. But despite my negative reaction to the princesses’ portrayals in what I could see in the trailer, and albeit I haven’t seen the full movie yet and my opinion may change when I do, I feel it’s still a good opportunity to raise a subject that has been increasingly conflicting in Disney as of late: the portrayal of their princesses, which has been erratic at best. So, in order for you to understand my point of view, we need to go a little further back in time than just the trailer. Come with me to a world of fantasy, dreams and pettiness.

The “Pixarization” of Disney Animation

One thing I’ve talked about before has been what I call the “pixarization” of Disney Animation in the last years, especially as the Pixar “Boys Club”, with Lasseter at the helm, took over Disney Animation.

We’ll get to Lasseter, I promise you, but let’s walk this one step at a time.

Disney buying Pixar in 2006 wasn’t the only factor that allowed this process, it was also directly linked to the fact that, while Disney Animation was struggling in their Post-Renaissance Era, Pixar was thriving in the box office and receiving critical acclaim, including many awards. It wasn’t a long shot to expect that Disney would want to rely more on those who were providing Pixar with successful films (whether they were as good as critically regarded is a personal and subjective matter I won’t discuss here, you all probably have your personal views on this, as do I).

The slow but steady influence of the Pixar folks into Disney Animation can be seen in events that go from very obviously influenced to more debatable things (including Disney’s decision, in 2013, to dismantle their hand-drawn animation division, shelving and cancelling all projects that relied on it to happen, including, very importantly for our current debate, Princess Academy, which was also probably furthered damaged by the legal conflict between directors David Kawena and Oliver Ciappa which didn’t happen at the time but could be a factor for us to never see it again, given that they were to direct together, but we’ll never know).

Like I said in another post, one of the many things to note about this process is related to the fact that Pixar’s founding feature length film, Toy Story, was done in the basis of being an “anti Disney” film, to stand out from the rest of the movies in the Renaissance. Up to Toy Story’s release, the movies were often characterized by the musical theater aspect, heavily influenced by Ashman & Menken, and the resurrection of the Disney Princesses, after 30 years without them.

“John Lasseter has said that the first thing they did when they began thinking about Toy Story was to make a list of things that they did not want to be in it. Foremost among these was anything that resembled the ingredients of Disney movies of the period. (…) The Toy Story Brain Trust had grown up with movies, television situation comedies, and action shows rather than Broadway extravaganzas. They decided to make a buddy picture”. (x)

Like I said in that post, one of the characteristics of this “pixarization” has been to try to mock previous Disney tropes instead of reconstructing them, very much like Katzenberg-era Dreamworks attempted, but in a less crass manner, if you will.

And here’s the main point of my essay, folks: deconstructing a trope and destroying a trope are not the same thing.

When you deconstruct a trope or an archetype, you need to understand it, study it, dissect it and criticize it in order to build upon it a different perspective. When you destroy one, you’re mocking it, denigrating it, in order to make a different version seem better by comparison. Deconstructing, you build upon what was there before, respecting its basis but understanding its limitations and extending its boundaries. Destroying, you eliminate what was there and devalue its existence.

But let’s put all the cards on the table and give a few clarifying examples.

The deconstruction of the archetype: Enchanted & Tangled, the series

We’ll begin with what I call the deconstruction of the Disney Princess “archetype”.

The first good example of Princess trope deconstruction I can think of is Giselle from Enchanted (2007).

In my opinion, Enchanted is, to the Revival Era, what Roger Rabbit was to the Renaissance Era. I think (for a lot of reasons too long and off topic to disclose in this post) that the Disney Renaissance wouldn’t have been what it was without the push of a game changer like Roger Rabbit, and Enchanted gave the Revival a push by bringing back old Disney tropes (magic?) while successfully adapting it to a modern audience.

In the midst of that was Giselle, a Disney Princess through and through (although not in the official lineup for money reasons), who is placed in a context in which the archetype she’s built upon doesn’t work in the same way, but who doesn’t discard her identity in the process. Giselle’s development as a character isn’t in ditching her entire self because her context changed, but in learning through that context and adapting her own self to new experiences that evolve her character, while staying true to the same identity.

Giselle learns and grows, she is influenced by the modern perspective she’s inserted in, yet offers some of her own ideas and values to that new context, finding a balance between both. There is nothing wrong with being kind and generous, with being resourceful and dreamy, yet some of her ideas are too naive and hinder her own agency, which is what she ultimately learns. Giselle’s relationship with the modern context is one of mutual influence, not of transformation in exchange of her identity.

A more recent example, yet still in development, is Rapunzel through the Tangled series (2017).

Doing a Tangled show was a risk I didn’t expect Disney to take, considering that Tangled was, for the most part, a pretty self-sufficient movie. Still, the show is providing opportunities for not only movie characters to develop (I like Eugene 100% more in the series than I did in the movie) but also for new characters to add to the overall story line (Cassandra is an amazing addition to the main cast, Lance also provides a lot more to the story and, what can I say, I do like Varian quite a bit).

Rapunzel herself gets an unexpected development through the series, because her narrative of becoming a princess and having responsibilities goes further than just learning which fork goes with which food or what the names of the aristocrats are. Rapunzel isn’t a princess because she married a prince, she’s a princess by birth, and by Corona’s laws, it means she’ll be her father’s successor, not Eugene. And Rapunzel’s isolation during 18 years of her life are a tough burden when it comes to having an entire kingdom depending on her.

The series allows Rapunzel to make mistakes. Her entire plot with Varian is a turning point for the series and having an antagonist born from a close friend is a tougher narrative than what I’ve seen in a lot of similar premises. It was, ultimately, Rapunzel’s rejection what turned Varian around, and that was born from choosing what she thought she had to as a future Queen. And it hurts her. There isn’t right or wrong, it’s about making choices, and sometimes those choices change you in ways you didn’t expect.

Rapunzel’s princess status isn’t just a title and a crown, it’s becoming a task and a burden, and she’ll have to learn more about herself if she wants to be ready to rule. But that doesn’t mean she goes against who she was in the movie, it doesn’t mean she rejects her identity, it gets more complex, more complicated, as she grows up and the story develops. Her personality and identity are a key to her character development and her status as a princess is less romanticized as she realizes that there’s an entire kingdom depending on her choices and that sacrifices can take a toll on her own person and those she holds dear.

If you’re wondering why I’m not talking about Merida in this section, I promise she’ll come to my aid later. I haven’t forgotten her. I promise.

All of this doesn’t mean Enchanted and Tangled are bulletproof movies or that their narratives don’t have any issues whatsoever. What I’m focusing on here is in the development of the “princess archetype” and how the writing isn’t relying on them ditching their identities in order to develop as characters and fit more modern audiences or more complex story lines. Ok? Ok.

With these examples set for you to get what I mean by “deconstruction”, let’s move on to the opposite of this spectrum.

The destruction of the archetype: Wreck It Ralph, Frozen & Moana

Before I start with the examples of the destruction of this archetype, I want to clarify that my opinion on these uses of it do not mean that I dislike the movies or the characters themselves, but that I argue with the way in which the portrayal is conceived and why it is used in this way. As a human being with critical capacity I believe I’m able to like a thing and still find faults in it, something the internet can sometimes forget it’s possible, which is why I’m writing this essay in the first place. So don’t take my comments as condemning the movies or the characters in general. Please. I beg of you.

Chronologically, we have to start with Vanellope von Schweetz from Wreck It Ralph (2012). I’ll make a small comment on her because we’ll come back when discussing the trailer properly, but I’m interested in showcasing her specifically because she became a bit of a starting point for this destructive attitude towards princesses.

The status of Vanellope as a princess is a reveal in the movie, which is constructed in both the plot of the film (she was supposedly a glitch) and her personality. Vanellope’s character is a lot less independently conceived once you realize she was meant to throw you off from the fact that she’s actually a princess, because all her traits and quirks become less of her own design and more of a list of things “a princess wouldn’t be like”. For her status to be a surprise, you need to be presented with a conception of what the story line presents as the furthest from the archetype.

This is accentuated in the last portion of the film, when she rejects her title, discards her pink fluffy dress and makes jokes as to what she’ll do with the people who bullied her. She treats the idea of being a princess like lesser than a “president”, in this very P!nk in 2006 idea of what a girl should want and what she shouldn’t.

All of this didn’t seem that questionable at the time, because we were unaware of the overall context that she was inscribed in. Vanellope isn’t a character in a vacuum rejecting an idea of femininity, she’s one in an ongoing list of “anti Disney” ingredients, and her being around princesses was a moment to make or break this, but we’ll discuss the trailer later.

Let’s move on to Frozen (2013). And isn’t this a complicated subject to talk about on the internet.

To start, we need to make something very clear: Frozen is a movie that is based on one of the most female-centric fairy tales that exist. The Snow Queen places a girl in the center of the story, who has to rescue a boy and goes through an array of diverse female characters who will either hinder or help her throughout the way. So, contrary to popular belief, Frozen’s idea of not centering its premise in romantic love and putting female characters in the forefront isn’t really as unexpected as it’s often regarded (as it isn’t either having at least one female character who is often interpreted as gay, homosexuality not being a rare theme for Hans Christian Andersen for personal reasons, and which is also present in The Snow Queen). But we digress. I just wanted to put that out there first and foremost, because we’re talking about being “progressive” here.

My favorite part of Frozen is Elsa. I love Elsa, I love what she stands for, I love what she represents. She could be a step forward for Disney princesses (I know, she’s a Queen, but you know what I mean) because she’s offering a glimpse of something I’ve been asking for Disney heroines to have: to be allowed to mess up and make conflicting choices.

For ages Disney heroes have been allowed all the messes in the world. They’ve been liars, thieves, jerks, tricksters, diamonds in the rough. They’ve been questionable characters who are allowed to learn from their mistakes (sometimes repeating them a lot) in order to grow up and become better people. Nobody has been worried that their kid would learn to become a liar or a thief because a Disney hero starts up as one.

Princesses, on the other hand, haven’t had that choice. Historically, they’ve been set as examples of good and honorable behavior, in which their mistakes, if we could call them that, are excused or diminished by the narrative of their stories. They are always well-intentioned, always kind-hearted, and if they ever mess up, it isn’t a big deal. Yes, Ariel wasn’t the most responsible girl, but she was 16 and wanted to know a world her overprotective father denied her to even be close to. Yes, Tiana was missing some important things in sight, but she did so because she was working harder than anyone for a dream that was hers and her dad’s. Yes, Mulan lied, but she did it to save her father and, in the meantime, saved China. Yes, Merida messes up, but she’s trying to get her mother to understand that she can’t lose herself for a man she hasn’t met so she can appease a kingdom that clearly doesn’t respect her much if they expect that from her.

The only female heroine I can think of whose actions could be seen as knowing mistakes and who grew from them was Meg from Hercules. In that movie, Hercules is more what a typical Disney Princess is: new to the world, having his first adventure, kind-hearted and heroic, wants to see the world and know himself through it. Meg, in this scenario, is the Disney Prince: has already an experience in life and love, has been treated badly in it, is trying to move on with the coping mechanisms she has at hand and tries to let feelings out of her choices in order to do whatever it takes to get back her freedom. Meg actively helps Hades, up to a certain point, knowing that Hercules is a good guy, but she values her freedom more and is about to see him die in the hands of a Hydra. By the time she sacrifices herself for him, she has learned, evolved and become a new version of herself, willing to open herself to feelings once more.

Elsa is a step towards this, without fully getting here. Because yes, Elsa isn’t the typical princess, but she isn’t in Meg territory either. Her development creates a complex character, representing mental illness with a narrative devoid of key external influence, who goes through an internal path of discovery and identity, which is quite remarkable in Disney storytelling. Elsa’s biggest enemy is, ultimately, herself, self-acceptance and a quest for identity that is hindered by guilt-induced isolation.

But then, there’s Anna. And with Anna, comes the thing. The “you can’t marry a guy you just met” thing.

Frozen wasn’t the first movie to address this (Brave came out before, let’s remember, and Enchanted also included this topic among the tropes it discussed). And it wasn’t either the first to place sisterly bond in the center of a girl-targeted Disney film...sisterly bond between an ice-powered white-haired teal-clothing-wearing girl and her chirpy bun-haired resourceful estranged sister who sacrifices herself to save her and who is ultimately saved by the power of that bond. Yes, I’m talking about Secret of the Wings.

But, in any case, this “don’t marry a guy you just met” thing was one of the topics they chose to address through the character of Anna.

Anna is the more “conventional” Disney Princess for the lineup. She is again the one that embodies goodness, whose mistakes are merely quirks, who is well-intentioned and kind-hearted, who is starting out in the world and this is her first adventure and experience with love. She was, in a way, a lot more of a safer bet for Disney than Elsa was but, on the other hand, she offered the possibility for a deconstruction, if they wanted one.

So, on the one hand, the movie plays with this idea of love at first sight and how it isn’t that simple. The movie intends to shatter the trope to shreds by making Hans not only uninterested in her but also using her for power and attempting to murder her and her sister (the topic of “surprise” Disney villains who aren’t a surprise anymore after having like 20 of them in a row is a subject for another post entirely).

But then, you have Kristoff. If Hans represents the oldie Disney Prince, at first sight, the Prince, the Charming, the Philip, the Eric type; then Kristoff is the “allowed to be flawed” Prince we got in the Renaissance, the Aladdin, the Beast, the John Smith, the Naveen, the Flynn Rider (Shang, my friends, is in an entirely different category, which sadly, we don’t have time to discuss that in this post).