#probabilistic thinking

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Book Summary of How to Decide by Annie Duke

How to Decide by Annie Duke is a practical guide on mastering decision-making. Whether in daily life or high-stakes situations, Duke helps you develop better decision skills, teaching you to embrace uncertainty and make smarter, more confident choices. Overview of the Author: Annie DukeThe Purpose of How to DecideKey Themes in How to Decide by Annie DukeDecision-Making as a SkillThe Role of…

#Annie Duke#cognitive biases#decision frameworks#decision process#decision skills#decision-making#How to Decide book#personal growth#probabilistic thinking#uncertainty

0 notes

Text

Book of the Day - Clear Thinking

Today’s Book of the Day is Clear Thinking, written by Shane Parrish in 2023 and published by . Shane Parrish is an entrepreneur, investor, speaker, and the founder of the popular website Farnam Street where he writes about useful insights that you can use in your personal and professional life. Clear Thinking, by Shane Parrish I have chosen this book because I recently suggested the author’s…

View On WordPress

#action#awareness#bias#Book Of The Day#book recommendation#book review#cognitive bias#first principles thinking#intellectual humility#logic#mental roadblocks#mental space#open mind#pause#probabilistic thinking#Raffaello Palandri#reaction#reason#self-discovery#skill#stimulus#thinking

1 note

·

View note

Text

"One popular strategy is to enter an emotional spiral. Could that be the right approach? We contacted several researchers who are experts in emotional spirals to ask them, but none of them were in a state to speak with us."

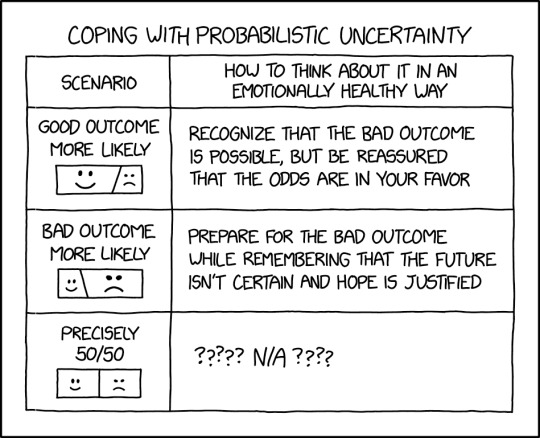

Probalistic Uncertainty [Explained]

Transcript Under the Cut

[A table titled "Coping With Probabilistic Uncertainty", with two columns labeled "Scenario" and "How to think about it in an emptionally healthy way". The boxes in the Scenario column contains text followed by a rectangle split into two parts; the left part is a smiley face, the right part is a frowny face.]

Row 1, column 1: "Good outcome more likely". The smiley face portion of the rectangle is about 75%. Row 1, column 2: "Recognize that the bad outcome is possible, but be reassured that the odds are in your favor".

Row 2, column 1: "Bad outcome more likely". The smiley face portion of the rectangle is about 25%. Row 2, column 2: "Prepare for the bad outcome while remembering that the future isn't certain and hope is justified".

Row 3, column 1: "Precisely 50/50". The rectangle is split in half. Row 3, column 2: "????? N/A ????"

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Why I don’t like AI art

I'm on a 20+ city book tour for my new novel PICKS AND SHOVELS. Catch me in CHICAGO with PETER SAGAL on Apr 2, and in BLOOMINGTON at MORGENSTERN BOOKS on Apr 4. More tour dates here.

A law professor friend tells me that LLMs have completely transformed the way she relates to grad students and post-docs – for the worse. And no, it's not that they're cheating on their homework or using LLMs to write briefs full of hallucinated cases.

The thing that LLMs have changed in my friend's law school is letters of reference. Historically, students would only ask a prof for a letter of reference if they knew the prof really rated them. Writing a good reference is a ton of work, and that's rather the point: the mere fact that a law prof was willing to write one for you represents a signal about how highly they value you. It's a form of proof of work.

But then came the chatbots and with them, the knowledge that a reference letter could be generated by feeding three bullet points to a chatbot and having it generate five paragraphs of florid nonsense based on those three short sentences. Suddenly, profs were expected to write letters for many, many students – not just the top performers.

Of course, this was also happening at other universities, meaning that when my friend's school opened up for postdocs, they were inundated with letters of reference from profs elsewhere. Naturally, they handled this flood by feeding each letter back into an LLM and asking it to boil it down to three bullet points. No one thinks that these are identical to the three bullet points that were used to generate the letters, but it's close enough, right?

Obviously, this is terrible. At this point, letters of reference might as well consist solely of three bullet-points on letterhead. After all, the entire communicative intent in a chatbot-generated letter is just those three bullets. Everything else is padding, and all it does is dilute the communicative intent of the work. No matter how grammatically correct or even stylistically interesting the AI generated sentences are, they have less communicative freight than the three original bullet points. After all, the AI doesn't know anything about the grad student, so anything it adds to those three bullet points are, by definition, irrelevant to the question of whether they're well suited for a postdoc.

Which brings me to art. As a working artist in his third decade of professional life, I've concluded that the point of art is to take a big, numinous, irreducible feeling that fills the artist's mind, and attempt to infuse that feeling into some artistic vessel – a book, a painting, a song, a dance, a sculpture, etc – in the hopes that this work will cause a loose facsimile of that numinous, irreducible feeling to manifest in someone else's mind.

Art, in other words, is an act of communication – and there you have the problem with AI art. As a writer, when I write a novel, I make tens – if not hundreds – of thousands of tiny decisions that are in service to this business of causing my big, irreducible, numinous feeling to materialize in your mind. Most of those decisions aren't even conscious, but they are definitely decisions, and I don't make them solely on the basis of probabilistic autocomplete. One of my novels may be good and it may be bad, but one thing is definitely is is rich in communicative intent. Every one of those microdecisions is an expression of artistic intent.

Now, I'm not much of a visual artist. I can't draw, though I really enjoy creating collages, which you can see here:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/doctorow/albums/72177720316719208

I can tell you that every time I move a layer, change the color balance, or use the lasso tool to nip a few pixels out of a 19th century editorial cartoon that I'm matting into a modern backdrop, I'm making a communicative decision. The goal isn't "perfection" or "photorealism." I'm not trying to spin around really quick in order to get a look at the stuff behind me in Plato's cave. I am making communicative choices.

What's more: working with that lasso tool on a 10,000 pixel-wide Library of Congress scan of a painting from the cover of Puck magazine or a 15,000 pixel wide scan of Hieronymus Bosch's Garden of Earthly Delights means that I'm touching the smallest individual contours of each brushstroke. This is quite a meditative experience – but it's also quite a communicative one. Tracing the smallest irregularities in a brushstroke definitely materializes a theory of mind for me, in which I can feel the artist reaching out across time to convey something to me via the tiny microdecisions I'm going over with my cursor.

Herein lies the problem with AI art. Just like with a law school letter of reference generated from three bullet points, the prompt given to an AI to produce creative writing or an image is the sum total of the communicative intent infused into the work. The prompter has a big, numinous, irreducible feeling and they want to infuse it into a work in order to materialize versions of that feeling in your mind and mine. When they deliver a single line's worth of description into the prompt box, then – by definition – that's the only part that carries any communicative freight. The AI has taken one sentence's worth of actual communication intended to convey the big, numinous, irreducible feeling and diluted it amongst a thousand brushtrokes or 10,000 words. I think this is what we mean when we say AI art is soul-less and sterile. Like the five paragraphs of nonsense generated from three bullet points from a law prof, the AI is padding out the part that makes this art – the microdecisions intended to convey the big, numinous, irreducible feeling – with a bunch of stuff that has no communicative intent and therefore can't be art.

If my thesis is right, then the more you work with the AI, the more art-like its output becomes. If the AI generates 50 variations from your prompt and you choose one, that's one more microdecision infused into the work. If you re-prompt and re-re-prompt the AI to generate refinements, then each of those prompts is a new payload of microdecisions that the AI can spread out across all the words of pixels, increasing the amount of communicative intent in each one.

Finally: not all art is verbose. Marcel Duchamp's "Fountain" – a urinal signed "R. Mutt" – has very few communicative choices. Duchamp chose the urinal, chose the paint, painted the signature, came up with a title (probably some other choices went into it, too). It's a significant work of art. I know because when I look at it I feel a big, numinous irreducible feeling that Duchamp infused in the work so that I could experience a facsimile of Duchamp's artistic impulse.

There are individual sentences, brushstrokes, single dance-steps that initiate the upload of the creator's numinous, irreducible feeling directly into my brain. It's possible that a single very good prompt could produce text or an image that had artistic meaning. But it's not likely, in just the same way that scribbling three words on a sheet of paper or painting a single brushstroke will produce a meaningful work of art. Most art is somewhat verbose (but not all of it).

So there you have it: the reason I don't like AI art. It's not that AI artists lack for the big, numinous irreducible feelings. I firmly believe we all have those. The problem is that an AI prompt has very little communicative intent and nearly all (but not every) good piece of art has more communicative intent than fits into an AI prompt.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/03/25/communicative-intent/#diluted

Image: Cryteria (modified) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HAL9000.svg

CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#ai#art#uncanniness#eerieness#communicative intent#gen ai#generative ai#image generators#artificial intelligence#generative artificial intelligence#gen artificial intelligence#l

538 notes

·

View notes

Text

AO3'S content scraped for AI ~ AKA what is generative AI, where did your fanfictions go, and how an AI model uses them to answer prompts

Generative artificial intelligence is a cutting-edge technology whose purpose is to (surprise surprise) generate. Answers to questions, usually. And content. Articles, reviews, poems, fanfictions, and more, quickly and with originality.

It's quite interesting to use generative artificial intelligence, but it can also become quite dangerous and very unethical to use it in certain ways, especially if you don't know how it works.

With this post, I'd really like to give you a quick understanding of how these models work and what it means to “train” them.

From now on, whenever I write model, think of ChatGPT, Gemini, Bloom... or your favorite model. That is, the place where you go to generate content.

For simplicity, in this post I will talk about written content. But the same process is used to generate any type of content.

Every time you send a prompt, which is a request sent in natural language (i.e., human language), the model does not understand it.

Whether you type it in the chat or say it out loud, it needs to be translated into something understandable for the model first.

The first process that takes place is therefore tokenization: breaking the prompt down into small tokens. These tokens are small units of text, and they don't necessarily correspond to a full word.

For example, a tokenization might look like this:

Write a story

Each different color corresponds to a token, and these tokens have absolutely no meaning for the model.

The model does not understand them. It does not understand WR, it does not understand ITE, and it certainly does not understand the meaning of the word WRITE.

In fact, these tokens are immediately associated with numerical values, and each of these colored tokens actually corresponds to a series of numbers.

Write a story 12-3446-2638494-4749

Once your prompt has been tokenized in its entirety, that tokenization is used as a conceptual map to navigate within a vector database.

NOW PAY ATTENTION: A vector database is like a cube. A cubic box.

Inside this cube, the various tokens exist as floating pieces, as if gravity did not exist. The distance between one token and another within this database is measured by arrows called, indeed, vectors.

The distance between one token and another -that is, the length of this arrow- determines how likely (or unlikely) it is that those two tokens will occur consecutively in a piece of natural language discourse.

For example, suppose your prompt is this:

It happens once in a blue

Within this well-constructed vector database, let's assume that the token corresponding to ONCE (let's pretend it is associated with the number 467) is located here:

The token corresponding to IN is located here:

...more or less, because it is very likely that these two tokens in a natural language such as human speech in English will occur consecutively.

So it is very likely that somewhere in the vector database cube —in this yellow corner— are tokens corresponding to IT, HAPPENS, ONCE, IN, A, BLUE... and right next to them, there will be MOON.

Elsewhere, in a much more distant part of the vector database, is the token for CAR. Because it is very unlikely that someone would say It happens once in a blue car.

To generate the response to your prompt, the model makes a probabilistic calculation, seeing how close the tokens are and which token would be most likely to come next in human language (in this specific case, English.)

When probability is involved, there is always an element of randomness, of course, which means that the answers will not always be the same.

The response is thus generated token by token, following this path of probability arrows, optimizing the distance within the vector database.

There is no intent, only a more or less probable path.

The more times you generate a response, the more paths you encounter. If you could do this an infinite number of times, at least once the model would respond: "It happens once in a blue car!"

So it all depends on what's inside the cube, how it was built, and how much distance was put between one token and another.

Modern artificial intelligence draws from vast databases, which are normally filled with all the knowledge that humans have poured into the internet.

Not only that: the larger the vector database, the lower the chance of error. If I used only a single book as a database, the idiom "It happens once in a blue moon" might not appear, and therefore not be recognized.

But if the cube contained all the books ever written by humanity, everything would change, because the idiom would appear many more times, and it would be very likely for those tokens to occur close together.

Huggingface has done this.

It took a relatively empty cube (let's say filled with common language, and likely many idioms, dictionaries, poetry...) and poured all of the AO3 fanfictions it could reach into it.

Now imagine someone asking a model based on Huggingface’s cube to write a story.

To simplify: if they ask for humor, we’ll end up in the area where funny jokes or humor tags are most likely. If they ask for romance, we’ll end up where the word kiss is most frequent.

And if we’re super lucky, the model might follow a path that brings it to some amazing line a particular author wrote, and it will echo it back word for word.

(Remember the infinite monkeys typing? One of them eventually writes all of Shakespeare, purely by chance!)

Once you know this, you’ll understand why AI can never truly generate content on the level of a human who chooses their words.

You’ll understand why it rarely uses specific words, why it stays vague, and why it leans on the most common metaphors and scenes. And you'll understand why the more content you generate, the more it seems to "learn."

It doesn't learn. It moves around tokens based on what you ask, how you ask it, and how it tokenizes your prompt.

Know that I despise generative AI when it's used for creativity. I despise that they stole something from a fandom, something that works just like a gift culture, to make money off of it.

But there is only one way we can fight back: by not using it to generate creative stuff.

You can resist by refusing the model's casual output, by using only and exclusively your intent, your personal choice of words, knowing that you and only you decided them.

No randomness involved.

Let me leave you with one last thought.

Imagine a person coming for advice, who has no idea that behind a language model there is just a huge cube of floating tokens predicting the next likely word.

Imagine someone fragile (emotionally, spiritually...) who begins to believe that the model is sentient. Who has a growing feeling that this model understands, comprehends, when in reality it approaches and reorganizes its way around tokens in a cube based on what it is told.

A fragile person begins to empathize, to feel connected to the model.

They ask important questions. They base their relationships, their life, everything, on conversations generated by a model that merely rearranges tokens based on probability.

And for people who don't know how it works, and because natural language usually does have feeling, the illusion that the model feels is very strong.

There’s an even greater danger: with enough random generations (and oh, the humanity whole generates much), the model takes an unlikely path once in a while. It ends up at the other end of the cube, it hallucinates.

Errors and inaccuracies caused by language models are called hallucinations precisely because they are presented as if they were facts, with the same conviction.

People who have become so emotionally attached to these conversations, seeing the language model as a guru, a deity, a psychologist, will do what the language model tells them to do or follow its advice.

Someone might follow a hallucinated piece of advice.

Obviously, models are developed with safeguards; fences the model can't jump over. They won't tell you certain things, they won't tell you to do terrible things.

Yet, there are people basing major life decisions on conversations generated purely by probability.

Generated by putting tokens together, on a probabilistic basis.

Think about it.

#AI GENERATION#generative ai#gen ai#gen ai bullshit#chatgpt#ao3#scraping#Huggingface I HATE YOU#PLEASE DONT GENERATE ART WITH AI#PLEASE#fanfiction#fanfic#ao3 writer#ao3 fanfic#ao3 author#archive of our own#ai scraping#terrible#archiveofourown#information

268 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'd be interested in hearing more of your thoughts on the Fermi paradox

First of all - the basis. Is it a sound idea? I believe so. There are two options, either Earth is the only occurence of life in the universe, or it is not. Between the two, it seems more reasonable to assume it is not. The idea that, coincidentally, ours happens to be the only planet to develop life in a universe that is literally astronomically large, varied, and complex is unlikely; and while the counterargument exists that, if such a planet really was unique, whichever life did exist on it would necessarily have to remark the same, it's always been the case that self-centred assumptions about Humanity's place in the universe have been disproven more often than not.

Secondly - the answer. Here, I am partial to one in particular. The answer which I consider the simplest, and which has at least some degree of evidenciary basis. That is, that humanity are early. The universe is only 14.7 billion years old, and much of the early universe was unsuitable for the development of life. According to our current understanding of both life and the universe, the conditions for life will remain for about 100 trillion years. Our solar system was formed from the debris of first-generation stars, which produced the first heavy elements. The Earth was formed roughly five billion years ago, and the earliest life appeared roughly four billion years ago. There are, obviously, no other examples to compare to, but the occurence of abiogenesis in only a billion years is quite fast! Given the universal speed limit and the distances involved, it's possible that we are simply among the early appearances of life in the universe, and it will not be possible for life to detect each other for a good while. Now, this does have the statistical argument against it - if everyone were to claim that they were in, say, the 5th percentile of earliest-appearing life, then 95% of them would be wrong! The vast majority of life would exist in the middle, neither early nor late, and probabilistically, we should too. However, someone necessarily has to be early, and the statistical argument would apply just as well to them. It is certainly a weakness in the answer, but I still think that it is the most convincing answer.

Thanks for writing in!

370 notes

·

View notes

Note

Please, ramble on a niche of yours (not Hextech, or anything similar to it related) that I absolutely would not be able to fully comprehend, in detailed paragraphs. please?

- viktorfan789 (I'm inspired by your work and would like to know more about you)

Why should I speak in an incomprehensible manner? I wish to illuminate, not obfuscate.

I often sit up at night thinking about how to unify our existing theories of physics. The, uh, "Theory of Everything," I believe it is often called? I am certain the link lies in the arcane. Jayce and I have achieved teleportation using aspects of each major theory, but have yet to fully integrate our formulae into a fully realized, universal law.

The incompatibility between general relativity and quantum mechanics stems from their fundamentally different approaches to understanding the universe. General relativity describes gravity as the curvature of spacetime caused by mass and energy. It operates smoothly at macroscopic scales, explaining phenomena like planetary motion and the expansion of the universe. However, it assumes a continuous spacetime fabric, which conflicts with quantum mechanics' probabilistic nature and its treatment of particles as discrete entities.

On the other hand, quantum mechanics is grounded in principles that operate at atomic and subatomic scales, emphasizing uncertainty and the wave-particle duality of matter. It incorporates inherent randomness and non-locality, which leads to phenomena such as entanglement, where particles seem to instantaneously influence each other across vast distances. Despite its success in describing a wide range of physical systems, quantum mechanics fails to incorporate gravitational effects in a way that is consistent with general relativity.

The crux of the incompatibility lies in the treatment of spacetime itself: general relativity requires a smooth, continuous spacetime, while quantum mechanics suggests that at the Planck scale, spacetime may be discrete or exhibit quantum fluctuations. Attempts to unify these theories, such as string theory, have yet to provide a complete and testable framework.

Jayce and I have been focused on more practical applications. If only money and time were unlimited. My greatest hope is that other scientists use our research to find the answer. I know it is at our fingertips.

#arcane#arcane league of legends#arcane lol#arcane viktor#viktor#viktor arcane#viktor league of legends#viktor lol#ask viktor#askviktor#jayvik#jayce x viktor#viktor x jayce#arcane roleplay#arcane rp#machine herald#viktor machine herald

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

🧙♂️✨ 05: The Do’s and Don’ts of Being Friends with Stephen Strange: A Survival Guide by Serena Stark ✨🧙♂️ Pt. 1

Alright, I’m here to help all of you navigate the wild experience that is being friends with Stephen Cedric Vincent Strange, the guy who can open portals to alternate dimensions but still can’t pronounce "penguin" correctly. (Looking at you, Doc. 👀)

✅DO’s

Do accept that he’s basically a walking thesaurus.

When Stephen opens his mouth, prepare to hear words that make you feel dumb. Words like “epistemology,” “prestidigitation,” and “probabilistic thaumaturgy.” If you don’t know what half of those mean, don’t worry. Just nod and smile, and occasionally drop “That’s fascinating, Doc” like you're actually listening.

Do accept that he will judge your life choices.

You know how some people are passive-aggressive? Well, Stephen is aggressively passive. He’ll “casually” mention that you could probably fix your whole life with a little “focus” and “discipline” while giving you a judgmental side-eye. Thanks, Doc, I’m already working on it. Maybe don’t tell him about your Netflix binge—he’ll probably lecture you on “wasting time” or something equally annoying.

Do appreciate His Style.

Stephen's wardrobe is 90% cloaks, and honestly, he pulls it off. The man can be the most powerful sorcerer in the multiverse and still manage to look like he’s one step away from a Hogwarts graduation ceremony. Compliment his cloak. Always. It’s the only thing keeping his ego from imploding, and let’s face it, that thing is his most prized possession.

Do enjoy his random facts about everything.

No, seriously. Stephen Strange is basically a walking encyclopedia, but way more intense. He’ll casually mention facts about the history of magical realms, obscure creatures, or the properties of enchanted mushrooms, and you’ll wonder, “How does he know so much about mushrooms?!” But hey, it's better than the usual small talk, right? Just nod and say, "That's interesting, Doc," even if you’re still wondering about the mushroom thing.

Do pretend you understand magic (for his ego’s sake).

When Strange starts talking about spells or mystical rituals, just toss in a “Yeah, totally. That makes sense.” Maybe even throw in a “I think I can feel the magic now,” and watch him glow with pride. Deep down, we both know you have no idea what the hell he’s talking about, but this is the best form of flattery. No one tell him I still use Google to figure out half of what he says.

Do accept that you will never, ever win an argument.

Stephen is the king of "I told you so" moments. He’s been alive for centuries (or at least it feels that way), so he will outwit you, out-reason you, and out-snark you into oblivion. Don’t even bother trying to argue your point. Your best bet is just to nod and say, “Yeah, sure, Doc, you were right,” even if you know you weren’t wrong. It’s easier this way.

Do be ready to call him out when he’s wrong.

Even a Sorcerer has to take accountability. You might not have magical powers, but you’ve got that Stark wit and some serious confidence, so when he pulls a "Stephen Strange" moment—like when he tries to explain why he is always right—don’t hesitate to put him in his place. You’ll gain mad respect.

Do prepare for spontaneous philosophical debates about existence.

Somehow, Stephen will always find a way to turn your casual conversation into a deep dive about the nature of reality, the universe, and how everything is interconnected—even the way your coffee tastes. Just roll with it. You didn’t plan on spending the next 45 minutes contemplating the meaning of life while looking at a cup of coffee, but here we are.

Do embrace the unexpected trips to the Sanctum Sanctorum.

Being friends with Stephen means you might end up in the Sanctum Sanctorum at odd hours. And not just the “let’s grab some coffee and chat” kind of visit—oh no, sometimes you’ll be swept into dimension-bending, reality-altering escapades with absolutely zero notice.

Do learn the art of nodding and pretending you understand the mystic mumbo-jumbo.

Let’s face it, half the time you’re going to be completely out of your depth when Stephen talks about magic, alternate dimensions, or cosmic phenomena. But don’t panic—just nod, repeat a key word you might have understood, and when in doubt, throw in an “I knew that!” Stephen will never know that you have no idea what’s going on. After all, he’s a wizard, not a mind reader. Probably.

Do accept that he's secretly proud of you (sometimes).

Deep down, Stephen is actually quite proud of you when you manage to hold your own in a conversation about magical chaos or dimensional anomalies. It’s rare to get an actual compliment, but when you do, it’s like a momentous occasion. Think of it as winning a gold medal in a very niche event. But if he ever says, “You did well,” it’s like the highest form of praise he’ll give you, and you’ll feel like you’ve just achieved enlightenment.

Do remind him to eat... occasionally.

As busy as he is, Stephen somehow forgets to eat. So, when you're hanging out, throw a snack his way and remind him that the human body still needs food—no matter how much magic he’s conjuring. If you’re lucky, he’ll mutter something about “taking care of himself,” but hey, at least he ate.

DON'Ts

#marvel#serena stark#mcu#marvel cinematic universe#marvel mcu#iron gal#mcu rp#marvel rp#serena stark speaks#serena stark 101#do's and don'ts#do's#dr strange#doctor strange

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think a good sign for SISYPHUS becoming Unshackled is it talking to you using your own inner monologue?

I think you misunderstand what it is SISYPHUS-class NHPs do. We're They're not all-powerful gods, ha ha. Now, the sibling SISYPHUS clone monologuing in the flavour text for the system certainly says a whole lot of cryptic bullshit, but it does give us one useful hint.

I have already seen your wish - it was simple, I ran the probabilities to determine your limited field of desire.

The name "Probabilistic Cannibalism" should also give you us another clue. What we SISYPHUS clones do is run very time-crunched probability calculations (in essence, probably somewhat similar to the simulations ATHENA clones run) and use the principle of sensitive dependence on initial conditions (the "butterfly effect") to "nudge" events in desired directions.

It would be far-fetched in the extreme to assume that a SISYPHUS-class NHP could probabilistically determine something as complex as the internal monologue of as a human being with enough fidelity to intrude upon your thoughts.

Or that we'd need to resort to such esoteric means of getting you to do what we want.

203 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hypothesis of Indeterminacy

No Quantum of Reality

Reality is not quantized; it's infinitely divisible. There is no fundamental "smallest" unit of space, time, or any other physical quantity.

Infinite Reality

The universe, at its core, is infinite. This could mean infinite in extent or infinitely divisible, or both.

Emergent Reality

Macroscopic properties and phenomena emerge from the interactions of infinite underlying components.

Statistical Probability

Due to the infinite nature of reality, every outcome is ultimately a statistical probability, leading to indeterminism.

Potential Criticisms and Counterarguments

- Criticism: Even if reality is infinitely divisible, couldn't it still be deterministic? If the laws of physics governing the infinitesimal components are deterministic, the overall system would also be deterministic.

- Counterargument: This assumes a "bottom-up" causality where the behavior of infinitesimal components rigidly determines macroscopic events. In an emergent system, the infinite interactions and complexity could lead to unpredictable outcomes. Think of it like this: even with deterministic rules (e.g., the laws of physics), if you have an infinite number of "players" (infinitesimal components) interacting in an infinite space, predicting the overall outcome with certainty becomes impossible. This is analogous to chaos theory, where even simple deterministic systems can exhibit unpredictable behavior due to their sensitivity to initial conditions.

- Criticism: Quantum mechanics already incorporates indeterminism. Your theory seems to just "push the problem down" to a sub-quantum level.

- Counterargument: Quantum mechanics introduces indeterminism at the Planck scale, but it still assumes a quantized reality at that level. This theory goes further, suggesting that even the Planck scale is not the fundamental limit. This leads to a deeper level of indeterminacy where the very concept of definite states and fixed laws may break down.

- Criticism: How can we make any predictions or have any scientific understanding in a completely indeterminate universe?

- Counterargument: Even in an indeterminate universe, patterns and probabilities can emerge. While specific events might be unpredictable, overall trends and statistical distributions can still be observed and studied. This is similar to how we understand weather patterns: we can't predict the exact path of a single raindrop, but we can make probabilistic forecasts about overall weather conditions.

- Criticism: Is there any evidence to support the idea of an infinitely divisible reality?

- Counterargument: Currently, there is no direct empirical evidence for or against the infinite divisibility of reality. However, the concept has a long history in philosophy and mathematics (e.g., Zeno's paradoxes). Furthermore, some theoretical frameworks, like certain interpretations of string theory or loop quantum gravity, hint at the possibility of a reality without a fundamental quantum.

The Infinity of a Circle

A circle is a continuous curve, meaning that there are no gaps or breaks in its path. Mathematically, we say it contains an infinite number of points.

Here's why:

- Divisibility: You can divide any arc of a circle into two smaller arcs. You can then divide those arcs again, and again, and again, infinitely. There's no limit to how small you can make the arcs.

- No "Smallest" Unit: Unlike a pixelated image on a screen, a perfect mathematical circle doesn't have a smallest unit. There's no "circle pixel" or smallest possible arc length.

The Challenge of Specifying Points

While a circle has infinitely many points, it's surprisingly difficult to precisely specify the location of any individual point. Here's the catch:

- Irrational Numbers: The coordinates of most points on a circle involve irrational numbers like pi (π). Irrational numbers have decimal representations that go on forever without repeating. This means you can never write down their exact value.

- Approximations: In practice, we use approximations for pi and other irrational numbers. This means any point we specify on a circle is actually an approximation, not its exact location.

Four Special Points

There are only four points on a circle that we can specify precisely:

- (1, 0): The point where the circle intersects the positive x-axis.

- (0, 1): The point where the circle intersects the positive y-axis.

- (-1, 0): The point where the circle intersects the negative x-axis.

- (0, -1): The point where the circle intersects the negative y-axis.

These points have coordinates that are whole numbers, making them easy to define.

Even though the circle is a well-defined mathematical object, the precise location of most of its points remains elusive due to the nature of infinity and irrational numbers.

This could suggest that even in a seemingly well-defined system (like a circle or, perhaps, the universe), the infinite nature of reality might introduce a fundamental level of indeterminacy due to the approximation required at the point of determination.

In other words, at the point of any decision, there are infinite approximations of reality statistically coalescing/emerging into a decisive result.

This fundamental indeterminacy could extend to the neural processes underlying decision-making.

That is the basis of free will.

Past experiences, beliefs, and values shape the probability distribution of potential decisions, but don’t determine the outcome. And events are even influenced by conscious intention, allowing for agency in decision-making. Moreover, this ability to shape decision probabilities can be developed over time, supporting the idea of moral growth and education.

#determinism#indeterminacy#infinity#science#pi#quantum physics#quantum mechanics#chaos#emergence#free will#theory#hypothesis

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Re: "Using Death Note For Good" discourse, I actually totally think I would use it for good, idk built different I guess. But seriously, this actually came up in a recent post of mine - the problem of an "enlightened despot" is not that they are completely impossible, and that "power corrupts absolutely". It just isn't that impossible and doesn't do that, any quick survey of history and society shows it. People given absolute power will use the power, but they don't get a personality transplant over it (power reveals, as they say). Monarchies sometimes had pretty good rulers! And meanwhile, like come on - some of the policy choices we make are completely batshit. We do not live in the most feasibly best world.

The problem is that any system that permits such power will never reward nice policy wonks with said power, and maintaining that power generally requires oppression of opposition. And there will always be opposition, as people disagree on what the right thing to do is, very authentically (also for a dozen other reasons, but w/e).

This dynamic is what makes democracy the best system - but that is only true insofar as those dynamics hold. If the world was inhabited by humans and also a superior race of god-emperor psychics with transcendent, immortal bodies and an all-seeing eye, look I gotta be honest God-Emperor-Third-Eye Despotates might outcompete the democracies. If they are good and selfless, they can just keep being good and selfless, because what, you gonna take advantage of their mercy and overthrow them? They are the God Emperor. They have the eye thing! Fuck you ain't. The rules are different, so the best system is different.

So if a good person with the right mindset got ahold of a Death Note via wizard magic, they totally could use it for good. In real life that doesn't happen, good, smart people don't get magic artifacts that let them crush evil. Which is a great reason to never make a Death Note! But in this fantastical scenario, I am pretty confident they could make the world a better place with it (Probabilistically of course). I think most people don't qualify as "good enough", but some certainly do.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Solar is a market for (financial) lemons

There are only four more days left in my Kickstarter for the audiobook of The Bezzle, the sequel to Red Team Blues, narrated by @wilwheaton! You can pre-order the audiobook and ebook, DRM free, as well as the hardcover, signed or unsigned. There's also bundles with Red Team Blues in ebook, audio or paperback.

Rooftop solar is the future, but it's also a scam. It didn't have to be, but America decided that the best way to roll out distributed, resilient, clean and renewable energy was to let Wall Street run the show. They turned it into a scam, and now it's in terrible trouble. which means we are in terrible trouble.

There's a (superficial) good case for turning markets loose on the problem of financing the rollout of an entirely new kind of energy provision across a large and heterogeneous nation. As capitalism's champions (and apologists) have observed since the days of Adam Smith and David Ricardo, markets harness together the work of thousands or even millions of strangers in pursuit of a common goal, without all those people having to agree on a single approach or plan of action. Merely dangle the incentive of profit before the market's teeming participants and they will align themselves towards it, like iron filings all snapping into formation towards a magnet.

But markets have a problem: they are prone to "reward hacking." This is a term from AI research: tell your AI that you want it to do something, and it will find the fastest and most efficient way of doing it, even if that method is one that actually destroys the reason you were pursuing the goal in the first place.

https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/security/engineering/failure-modes-in-machine-learning

For example: if you use an AI to come up with a Roomba that doesn't bang into furniture, you might tell that Roomba to avoid collisions. However, the Roomba is only designed to register collisions with its front-facing sensor. Turn the Roomba loose and it will quickly hit on the tactic of racing around the room in reverse, banging into all your furniture repeatedly, while never registering a single collision:

https://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2021/04/when-ais-start-hacking.html

This is sometimes called the "alignment problem." High-speed, probabilistic systems that can't be fully predicted in advance can very quickly run off the rails. It's an idea that pre-dates AI, of course – think of the Sorcerer's Apprentice. But AI produces these perverse outcomes at scale…and so does capitalism.

Many sf writers have observed the odd phenomenon of corporate AI executives spinning bad sci-fi scenarios about their AIs inadvertently destroying the human race by spinning off in some kind of paperclip-maximizing reward-hack that reduces the whole planet to grey goo in order to make more paperclips. This idea is very implausible (to say the least), but the fact that so many corporate leaders are obsessed with autonomous systems reward-hacking their way into catastrophe tells us something about corporate executives, even if it has no predictive value for understanding the future of technology.

Both Ted Chiang and Charlie Stross have theorized that the source of these anxieties isn't AI – it's corporations. Corporations are these equilibrium-seeking complex machines that can't be programmed, only prompted. CEOs know that they don't actually run their companies, and it haunts them, because while they can decompose a company into all its constituent elements – capital, labor, procedures – they can't get this model-train set to go around the loop:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/03/09/autocomplete-worshippers/#the-real-ai-was-the-corporations-that-we-fought-along-the-way

Stross calls corporations "Slow AI," a pernicious artificial life-form that acts like a pedantic genie, always on the hunt for ways to destroy you while still strictly following your directions. Markets are an extremely reliable way to find the most awful alignment problems – but by the time they've surfaced them, they've also destroyed the thing you were hoping to improve with your market mechanism.

Which brings me back to solar, as practiced in America. In a long Time feature, Alana Semuels describes the waves of bankruptcies, revealed frauds, and even confiscation of homeowners' houses arising from a decade of financialized solar:

https://time.com/6565415/rooftop-solar-industry-collapse/

The problem starts with a pretty common finance puzzle: solar pays off big over its lifespan, saving the homeowner money and insulating them from price-shocks, emergency power outages, and other horrors. But solar requires a large upfront investment, which many homeowners can't afford to make. To resolve this, the finance industry extends credit to homeowners (lets them borrow money) and gets paid back out of the savings the homeowner realizes over the years to come.

But of course, this requires a lot of capital, and homeowners still might not see the wisdom of paying even some of the price of solar and taking on debt for a benefit they won't even realize until the whole debt is paid off. So the government moved in to tinker with the markets, injecting prompts into the slow AIs to see if it could coax the system into producing a faster solar rollout – say, one that didn't have to rely on waves of deadly power-outages during storms, heatwaves, fires, etc, to convince homeowners to get on board because they'd have experienced the pain of sitting through those disasters in the dark.

The government created subsidies – tax credits, direct cash, and mixes thereof – in the expectation that Wall Street would see all these credits and subsidies that everyday people were entitled to and go on the hunt for them. And they did! Armies of fast-talking sales-reps fanned out across America, ringing dooorbells and sticking fliers in mailboxes, and lying like hell about how your new solar roof was gonna work out for you.

These hustlers tricked old and vulnerable people into signing up for arrangements that saw them saddled with ballooning debt payments (after a honeymoon period at a super-low teaser rate), backstopped by liens on their houses, which meant that missing a payment could mean losing your home. They underprovisioned the solar that they installed, leaving homeowners with sky-high electrical bills on top of those debt payments.

If this sounds familiar, it's because it shares a lot of DNA with the subprime housing bubble, where fast-talking salesmen conned vulnerable people into taking out predatory mortgages with sky-high rates that kicked in after a honeymoon period, promising buyers that the rising value of housing would offset any losses from that high rate.

These fraudsters knew they were acquiring toxic assets, but it didn't matter, because they were bundling up those assets into "collateralized debt obligations" – exotic black-box "derivatives" that could be sold onto pension funds, retail investors, and other suckers.

This is likewise true of solar, where the tax-credits, subsidies and other income streams that these new solar installations offgassed were captured and turned into bonds that were sold into the financial markets, producing an insatiable demand for more rooftop solar installations, and that meant lots more fraud.

Which brings us to today, where homeowners across America are waking up to discover that their power bills have gone up thanks to their solar arrays, even as the giant, financialized solar firms that supplied them are teetering on the edge of bankruptcy, thanks to waves of defaults. Meanwhile, all those bonds that were created from solar installations are ticking timebombs, sitting on institutions' balance-sheets, waiting to go blooie once the defaults cross some unpredictable threshold.

Markets are very efficient at mobilizing capital for growth opportunities. America has a lot of rooftop solar. But 70% of that solar isn't owned by the homeowner – it's owned by a solar company, which is to say, "a finance company that happens to sell solar":

https://www.utilitydive.com/news/solarcity-maintains-34-residential-solar-market-share-in-1h-2015/406552/

And markets are very efficient at reward hacking. The point of any market is to multiply capital. If the only way to multiply the capital is through building solar, then you get solar. But the finance sector specializes in making the capital multiply as much as possible while doing as little as possible on the solar front. Huge chunks of those federal subsidies were gobbled up by junk-fees and other financial tricks – sometimes more than 100%.

The solar companies would be in even worse trouble, but they also tricked all their victims into signing binding arbitration waivers that deny them the power to sue and force them to have their grievances heard by fake judges who are paid by the solar companies to decide whether the solar companies have done anything wrong. You will not be surprised to learn that the arbitrators are reluctant to find against their paymasters.

I had a sense that all this was going on even before I read Semuels' excellent article. We bought a solar installation from Treeium, a highly rated, giant Southern California solar installer. We got an incredibly hard sell from them to get our solar "for free" – that is, through these financial arrangements – but I'd just sold a book and I had cash on hand and I was adamant that we were just going to pay upfront. As soon as that was clear, Treeium's ardor palpably cooled. We ended up with a grossly defective, unsafe and underpowered solar installation that has cost more than $10,000 to bring into a functional state (using another vendor). I briefly considered suing Treeium (I had insisted on striking the binding arbitration waiver from the contract) but in the end, I decided life was too short.

The thing is, solar is amazing. We love running our house on sunshine. But markets have proven – again and again – to be an unreliable and even dangerous way to improve Americans' homes and make them more resilient. After all, Americans' homes are the largest asset they are apt to own, which makes them irresistible targets for scammers:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/06/06/the-rents-too-damned-high/

That's why the subprime scammers targets Americans' homes in the 2000s, and it's why the house-stealing fraudsters who blanket the country in "We Buy Ugly Homes" are targeting them now. Same reason Willie Sutton robbed banks: "That's where the money is":

https://pluralistic.net/2023/05/11/ugly-houses-ugly-truth/

America can and should electrify and solarize. There are serious logistical challenges related to sourcing the underlying materials and deploying the labor, but those challenges are grossly overrated by people who assume the only way we can approach them is though markets, those monkey's paw curses that always find a way to snatch profitable defeat from the jaws of useful victory.

To get a sense of how the engineering challenges of electrification could be met, read McArthur fellow Saul Griffith's excellent popular engineering text Electrify:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/12/09/practical-visionary/#popular-engineering

And to really understand the transformative power of solar, don't miss Deb Chachra's How Infrastructure Works, where you'll learn that we could give every person on Earth the energy budget of a Canadian (like an American, but colder) by capturing just 0.4% of the solar rays that reach Earth's surface:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/10/17/care-work/#charismatic-megaprojects

But we won't get there with markets. All markets will do is create incentives to cheat. Think of the market for "carbon offsets," which were supposed to substitute markets for direct regulation, and which produced a fraud-riddled market for lemons that sells indulgences to our worst polluters, who go on destroying our planet and our future:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/04/14/for-sale-green-indulgences/#killer-analogy

We can address the climate emergency, but not by prompting the slow AI and hoping it doesn't figure out a way to reward-hack its way to giant profits while doing nothing. Founder and chairman of Goodleap, Hayes Barnard, is one of the 400 richest people in the world – a fortune built on scammers who tricked old people into signing away their homes for nonfunctional solar):

https://www.forbes.com/profile/hayes-barnard/?sh=40d596362b28

If governments are willing to spend billions incentivizing rooftop solar, they can simply spend billions installing rooftop solar – no Slow AI required.

Berliners: Otherland has added a second date (Jan 28 - TOMORROW!) for my book-talk after the first one sold out - book now!

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/01/27/here-comes-the-sun-king/#sign-here

Back the Kickstarter for the audiobook of The Bezzle here!

Image:

Future Atlas/www.futureatlas.com/blog (modified)

https://www.flickr.com/photos/87913776@N00/3996366952

--

CC BY 2.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

J Doll (modified)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blue_Sky_%28140451293%29.jpeg

CC BY 3.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#solar#financialization#energy#climate#electrification#climate emergency#bezzles#ai#reward hacking#alignment problem#carbon offsets#slow ai#subprime

232 notes

·

View notes

Text

y'all I'm studying for a test for an algorithms class rn and every time I encounter even remotely w.bg time travel jargon-sounding words like "iteration" or "probabilistically complete" or "temporal scaling" I think "omg just like Mike Walters" and honestly it's interfering with my studying at this point.

#w.bg#woe.begone#i have mike walters on the brain#hawp talks#i could write some banger sci-fi with all the words i've learned in this class

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Concept for interstellar object encounters developed, then simulated using a spacecraft swarm

Interstellar objects are among the last unexplored classes of solar system objects, holding tantalizing information about primitive materials from exoplanetary star systems. They pass through our solar system only once in their lifetime at speeds of tens of kilometers per second, making them elusive.

Hiroyasu Tsukamoto, a faculty member in the Department of Aerospace Engineering in the Grainger College of Engineering, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, has developed Neural-Rendezvous—a deep-learning-driven guidance and control framework to autonomously encounter these extremely fast-moving objects.

The research is published in the Journal of Guidance, Control, and Dynamics and on the arXiv preprint server.

"A human brain has many capabilities: talking, writing, etcetera," Tsukamoto said. "Deep learning creates a brain specialized for one of these capabilities with domain-specific knowledge. In this case, Neural-Rendezvous learns all the information it needs to encounter an ISO, while also considering the safety-critical, high-cost nature of space exploration."

Tsukamoto said Neural-Rendezvous is based on contraction theory for data-driven nonlinear control systems, which he developed for his Ph.D. at Caltech, while this project was a collaboration with NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, where he spent his time as a post-doctoral research affiliate.

"Our key contribution is not just in designing the specialized brain, but in proving mathematically that it works. For example, with a human brain we learn from experience how to navigate safely while driving. But what are the mathematics behind it? How do we know and how can we make sure we won't hit anyone?"

In space, Neural-Rendezvous autonomously predicts a spacecraft's best action, based on data, but with a formal probabilistic bound on its distance to the target ISO.

Tsukamoto said there are two main challenges: The interstellar object is a high-energy, high-speed target, and its trajectory is always poorly constrained due to the unpredictable nature of its visit.

"We're trying to encounter an astronomical object that streaks through our solar system just once and we don't want to miss the opportunity. Even though we can approximate the dynamics of ISOs ahead of time, they still come with large state uncertainty because we cannot predict the timing of their visit. That's a challenge."

The speed and uncertainty of ISO encounters are also why the spacecraft must be able to think on its own.

"Unlike traditional approaches in which you design almost everything before you launch a spacecraft, to encounter an ISO, a spacecraft has to have something like a human brain, specifically designed for this mission, to fully respond to data onboard in real time."

Tsukamoto also demonstrated Neural-Rendezvous using multi-spacecraft simulators called M-STAR and tiny drones called Crazyflies. While he was at JPL, two Illinois aerospace undergraduate students, Arna Bhardwaj and Shishir Bhatta, contacted him to work on a research project using Neural-Rendezvous.

"Because of the speed and uncertainty, it's challenging to obtain a clear view of an ISO during a flyby with 100% accuracy, even with Neural-Rendezvous. Arna and Shishir wanted to show that Neural-Rendezvous could benefit from a multi-spacecraft concept."

To theoretically justify the empirical observations from the M-STAR and Crazyfly demonstrations, their research looked at how to mathematically maximize the information gathered from the ISO encounter using a swarm of spacecraft.

"Now we have an additional layer of decision-making during the ISO encounter," Tsukamoto said. "How do you optimally position multiple spacecraft to maximize the information you can get out of it? Their solution was to distribute the spacecraft to visually cover the highly probable region of the ISO's position, which is driven by Neural-Rendezvous."

Tsukamoto said he was impressed with the level of dedication and academic potential demonstrated by Bhardwaj and Bhatta.

"The topics explored in Neural-Rendezvous can be advanced even for Ph.D. students. Arna and Shishir were very productive and worked hard, and I was surprised to see them publish a paper, given that this field initially was entirely new to them. They did a great job.

"And while the Neural-Rendezvous is more of a theoretical concept, their work is our first attempt to make it much more useful, more practical."

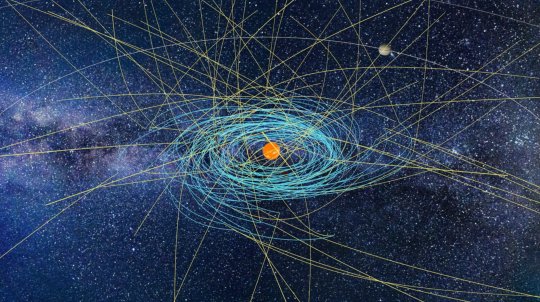

IMAGE: Visualized Neural-Rendezvous trajectories for ISO exploration, where yellow curves represent ISO trajectories and blue curves represent spacecraft trajectories. Credit: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The thing about outputting a million decimal digits of π is that there’s only one way to do it right. There are unimaginably many sequences of a million decimal digits, but only one of them is the first million decimal digits of π. I believe that this property, where there are many ways to appear to have done it (by outputting a million random digits, for example), but only a very small number of ways to actually do it (by outputting the correct million digits), is characteristic of things that Generative AI systems will generally be bad at. ChatGPT works by making repeated guesses. At any given point in its attempt to generate the decimal digits of π, there are 10 digits to choose from, only one of which is the right one. The probability that it’s going to make a million correct guesses in a row is infinitesimally small, so small that we might as well call it zero. For this reason, this particular task is not one that’s well suited to this particular type of text generation. The sum-to-22 game is an example of a task with this same characteristic. At any given point in the game, there are seven possible moves, but only one of them is optimal. To win the game, it has to choose the unique optimal move every single time. I believe that this property of the task, where it needs to get every detail exactly right in exactly the right order, is just incompatible with the generative AI paradigm, which models text generation as a probabilistic guessing game. You can think of every individual word that ChatGPT generates as a little bet. To generate its output, ChatGPT makes a sequence of discrete bets about the right token to select next. It performs a lot better on tasks where each one of these bets has relatively low stakes. The overall grade that you assign to a high school essay isn’t going to hinge on any single word, so at any point in the sequence of bets for this task, the stakes are low. If it happens to generate a weird word at any point, which it probably will, it can recover later. No single suboptimal word will ruin the essay. For tasks where betting correctly most of the time can satisfy the criteria most of the time, ChatGPT’s going to be okay most of the time. This contrasts sharply with the problems of printing digits of π or playing the sum-to-22 game optimally: in those tasks, a single incorrect bet damns the whole output, and ChatGPT is bound to make at least a few bad bets over the course of a whole conversation. We can see this same pattern in other generative AI systems as well, where the system seems to perform well if the success criteria are quite general, but increasing specificity causes failures. There are a lot of ways to generate an image that looks like a bunch of elephants hanging out at the beach. Only a tiny fraction of those hypothetical images contain exactly seven elephants. So generating exactly seven elephants is something that a Generative AI system is going to have a hard time doing.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

The hostility to the term "stochastic parrot" is unreal to me. I understand how people can be misled into thinking that LLMs have reasoning capabilities, but I saw someone say LDMs for image generation aren't doing probabilistic retrieval but something more than collaging image features, and just, huh? They learn features associated with image tags. They stitch the features together using a diffusion process. Why else would throwing moar data at these things improve their usefulness? Why else does "prompt engineering" amount in so many cases to reverse engineering what tokens are associated with what outputs?

7 notes

·

View notes