#trans!kit

Text

‼️Call/Write your Senators to STOP BILL S.1409 (KOSA)‼️

This is not my normal content but the word needs to spread

‼️KOSA IS A MASSIVE ONLINE CENSORSHIP BILL‼️

This bill is proposed by, Richard Blumenthal and Marsha Blackburn, who is very vocal about being against LGBT ppl!

It will force everyone online who wants to use a website to UPLOAD THEIR GOVERNMENT ID AND AGE TO THE PUBLIC!

Yes they did change the language of the bill but the sentiment is still the same. It will be used for censorship no matter what they say.

THIS BILL COULD PASS THE SENATE AS SOON AS NEXT WEEK AND THEN THE HOUSE THE SAME DAY

Omarsbigsister on TikTok is going into more detail.

This is so serious and will change the internet as we know it. People need to spread the word and call/write their senators.

Omarsbigsister on TikTok has videos and recourses on their page to help.

#lgbt#fuck kosa#stop kosa#kosa bill#politics#democrats#trans rights#lgbtq community#lgbt rights#online#transgender#fandom#kit talks#art#digital art

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

HAPPY PRIDE MONTH !! 🏳️🌈✨🏳️⚧️

LGBTQ+ rights , always and forever

#heartstopper#pride month#pride#lgbt#alice oseman books#charlie spring#heartstopper comfort#nick and charlie#nick nelson#osemanverse#alice oseman#kit connor#heartstopper pride#elle argent#darcy olsson#happy pride 🌈#trans pride#tara and darcy#elle and tao#love#love is love#love wins#osemanverse comfort#gay rights#gay#trans#bisexual#asexual#lesbian#lesbian rights

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Before We Were Trans by Kit Heyam

287 notes

·

View notes

Note

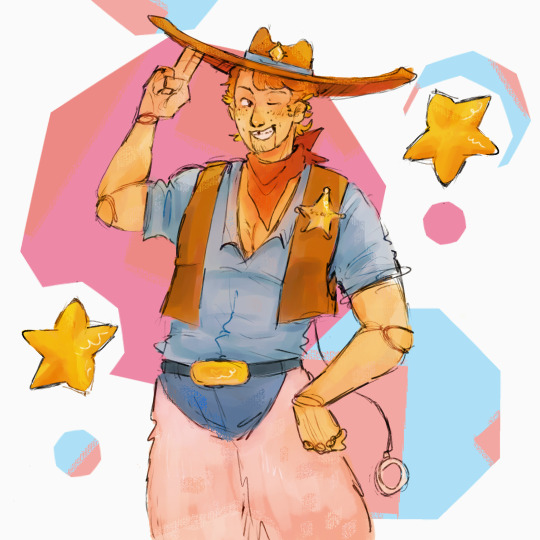

Could I maybe request a sheriff jimmy? Okay if not :]

sheriff jimmy loml

#jimmy solidarity#empires jimmy#empires#kit art#asks!#trans flag colour bg is intentionial btw shes a girl to me

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

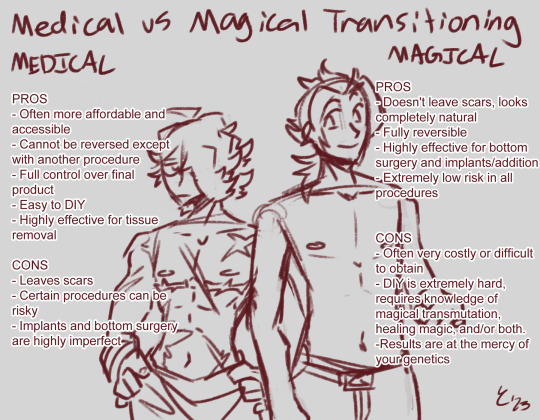

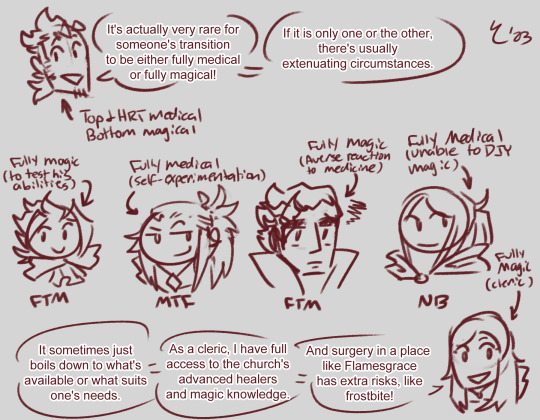

Three pages worth of details on Orsterran/Solistan transgender healthcare for no other reason than that its fun to think about

#spitblaze says things#octopath#octopath traveler#octopath traveler 2#therion#therion (octopath)#cyrus albright#alfyn greengrass#odette azelhart#olberic eisenberg#kit crossford#ophilia clement#castti florenz#tressa colzione#temenos mistral#feels like this should have a fourth page but i cant think of anything else. ah well#trans#transgender#spitblaze draws things

532 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spiderfam cat memes(ft.trans girl Miles)

#SOBBING AT THE MATCHING HEADGEAR#spiderfam#peter b parker#miles morales#transfem miles#mirasol morales#gwen stacy#trans gwen stacy#hobie brown#miguel o'hara#HELP I JUST NOTICED MIRASOL'S CAT HAS A WATCH BYE THIS MEME WAS MEANT FOR THEM DITXTJXJTTXJTJXD#atsv#spiderman#spidergirl#spidersiblings#summeredits#autistic girl summer#catkin#catgender#epic catgender momence#cat therian#kit cats#💌#summerposting#punkflower#t4t punkflower#< not shown but i have it in mind always........in their eternal boyfriend and girlfriend era#siblings!ghost punk

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

[“In a 2019 tweet (since deleted), Twitter user Brooke wrote of ‘carving “trans” into every bone of my body so when they find my skeleton in two hundred years they don’t get too confused’. A reply parodied the response of an oblivious archaeologist: ‘We must be careful not to jump to conclusions about what these ancient carvings could have meant; This individual could have had a passion for mass transit, transcontinental travel, or a combination of poor spelling and a love of trance music’.

Every time I read jokes like this, I get a jolt of hurt and defensiveness: not all historians and academics are like that! I try so hard, every day, not to do the kind of history they’re talking about! And yet I can hardly blame these people for talking and writing the way they do. The fact is that the discipline of history is set up to erase queer lives, and particularly trans lives. We are expected to adhere to double standards of evidence, which encourage us to state with impunity that a historical figure was definitely cis, but to hedge with caveats the suggestion that they were maybe, possibly trans; to use phrases like ‘cross-dresser’ or ‘impersonator’ as if they’re neutral, and to write lengthy defences of ourselves if we decide to avoid them; to expect backlash from colleagues and reviewers if we choose to use any pronouns for a historical figure other than those associated with the gender they were assigned at birth; to say, like the caricatured archaeologist above, ‘We must be careful not to jump to conclusions’, even when the evidence for trans experience is actually abundantly conclusive. It hurts when people memeify the oblivious, transphobic ‘historian’, but it’s also not unfair of them to do it. History, while it may not perpetuate physical harm, still repeatedly enacts violence against trans lives in the past and the present. And it’s not the job of the communities we’ve hurt to give us the benefit of the doubt: it’s our job to convince them that historians can be different.

In this book, I’ve identified new ways, and new places, to look for trans history. I’ve argued for the presence of trans experience in histories of gender-nonconforming fashion; histories of gender-nonconforming performance; and histories of people taking on a social role that isn’t associated with the gender they were assigned at birth. I’ve shown that many trans histories are inextricable from histories of other experiences: the sexual, the intersex, the anti-patriarchal, the spiritual. I’ve argued both for acknowledging trans possibility in histories of widespread gender nonconformity that have previously been explained in other ways, and for understanding gendered histories on their own terms – including seeing them, where necessary, as both trans history and the history of other kinds of people and experiences.

In this last kind of history in particular, I’ve often been confronted by what writer and philosopher Hil Malatino (quoting fellow scholar Abram J. Lewis) calls the ‘irreducible alterity’ of people in the past: the fact that some histories of gender are not possible to map onto or relate to the way people experience gender today. Malatino characterises the acknowledgement of this ‘irreducible alterity’ as a form of care for those past people, an idea that speaks deeply to me. It struck me, when I first read it, how different this framing of ‘care’ was from the arguments historians more commonly make against describing people in the past as trans: that it is presentist, that it is anachronistic, that it inappropriately fixes past people in modern categories. These arguments have rarely seemed to me to come from a place of care for people in the past; instead their priority seems to be history or historiographical methodology as an abstract, faux-objective entity. Still more rarely do they seem to acknowledge the concurrent urgency of caring for people in the present: the people who are living now, experiencing and articulating their gender in manifold ways and drawing strength from the histories of people who have done the same. Might it not be possible to find ways of recognising the essential difference of people in the past – people who disrupted gender before we were trans – while simultaneously holding space for the feelings of identification with them held by people in the present, the people who are trans now?”]

kit heyam, from before we were trans: a new history of gender, 2022

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

elle argent really is that girl

#she's also so gorgeous oh my <333#i love her so much#an angel#elle argent#beloved#heartstopper#yasmin finney#alice oseman#tao xu#elle x tao#art#trans rights#trans girls deserve the world#<3#queer joy#pride#nick nelson#kit connor#charlie spring#joe locke#tara jones#darcy olsson#tori spring

232 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Heartstopper.

#heartstopper#gay#lgbt#lgbtq#trans#transgender#asexual#queer#pan#bisexual#lesbian#kit connor#joe locke#photo#photography#portrait photography#digital collage#netflix#heartstopper cast#agosto2023#mood#tumblr#romance#drama#teen

349 notes

·

View notes

Text

this was so funny 😭

#tao was so funny this season#i was obsessed#😭😭#heartstopper#heartstopper spoilers#heartstopper season 2#heartstopper netflix#heartstopper comic#tao and elle#tao xu#elle argent#nick and charlie#nick nelson#charlie spring#kit connor#joe locke#lgbtq#gay#bisexual#trans#alice oseman#alice oseman art#osemanverse

271 notes

·

View notes

Text

im 5'1 and the thought of someone who is taller than me fucking me against a wall while they like kinda cage me in to make me feel smaller is so hot.

#t4t breeding#t4t ns/fw#nsft concept#queer nsft#t4t nsft#ftm breeding#ftm nsft#ftm ns/fw#trans nsft#nsft mlm#nsft mlnb#t4t sub#kit rambles

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Sometimes i'm a boy,sometimes i'm a girl,but i always want cat ears

#genderfluid#bigender#demigirl#catgender#catkin#cat therian#transmasc#transmasculine#trans men#💌#transfem#trans women#genderflux#trigender#demiboy#demigender#kit cats#trans humor#trans#trans memes#transgender#letters from summer#pop post 🌟

258 notes

·

View notes

Text

omg *cries*

credits: oliviapbells

#heartstopper#credits: oliviapbells#lgbtq#alice oseman#charlie spring#nick nelson#nick and charlie#joe locke#kit connor#gay pride#bisexual pride#lgbtq pride#lgbtq+#osemanverse#asexual pride#nick x charlie#charlie x nick#gay love#trans pride

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

heartstopper headers

“♡” or reblog if you save/use — follow me.

twt: @szamofada

#heartstopper#heartstopper headers#nick nelson#nick nelson headers#charlie spring#charlie spring headers#tao xu#elle argent#tara jones#darcy olsson#kit connor#joe locke#icons#headers#layouts#bisexual#gay#transgender#trans#lesbian#series#without psd#cinematography

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yeah i have no clue what y'all talking about with girl math or Lana del Rey or the female joker or female hysteria or female stimulator or however long the list is,when i say i'm a woman what i mean is this

#did not mean to make a personal moodboard when i started this post LMAO i was just trying to compe up with a caption for the first four pics#summercore#blackness#black femme#bigender#genderfluid#demigirl#transmasc#transmasculine#trans men#genderpunk#catkin#cat therian#catgender#dragonkin#dragon therian#dragongender#ghostkin#ghostgender#dragon tag#kit cats#food#therian tag#pastel punk tag#💌#summeredits#summerposting

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

[“A trans gaze can be an incredibly productive historiographical tool. A trans gaze is what allows us to look at a case of historical gender nonconformity and remain open to the full spectrum of possibilities it represents. A trans gaze is what allows us to read about an individual wearing a mixture of male- and female-coded clothing, and ask, ‘But what did that feel like?’ A trans gaze is what allows us to accept and take seriously the fact that a person’s gender can be a spiritual or sexual experience, in a way we can’t empathise with – or, indeed, that what looks like gender sometimes isn’t at all – because we know first-hand how it feels when people don’t take seriously how we articulate our selves. This is the gaze that I hope will continue to transform the way we think about the past.

The simple precept of knowing people on their own terms can transform more than history; it also has the power to liberate us in the present. I’ve shown throughout this book that the way we think about gender today is not natural or traditional but constructed and contingent; gender has always been open to disruption and challenge. This in itself is an important, potentially transformative realisation. But imagine if, alongside this, we could simply trust people to know their gendered selves – without prior assumptions, without constraining frameworks, without structures of assessment or judgement. When Faye argues that ‘The liberation of trans people would improve the lives of everyone in our society’; when Feinberg argues that ‘when [trans] lives are suppressed, everyone is denied an understanding of the rich diversity of sex and gender expression and experience that exist in human society’; this, I think, is key to what they mean.

People often ask me if I think we should aim for a future without gender, and while I usually feel a tinge of frustration at this kind of speculative enquiry (maybe we should, but we have gender now, so how do we pursue trans liberation in this society?), I always say that while the experience of having a gender is important to many people, there are lots of things about institutionalised, state-sanctioned gender that we could certainly do without. As Malatino puts it, ‘There are genders and there is Gender and I believe we can have the former without the latter’]

kit heyam, from before we were trans: a new history of gender, 2022

519 notes

·

View notes