#Red and Black Notes

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Anarchists and Neo-anarchists: Horizontalism and Autonomous Spaces

It is not uncommon, particularly in North America, to see anarchism defined as an ideology rooted in ‘direct democracy’, consensus decision making, and the maintenance of ‘horizontal’ (i.e., ‘non-hierarchical’) social relations, particularly in autonomous zones or public spaces.

This idea of anarchism is unusual in that it places at the centre of its definition an adherence to very specific forms of procedure and interpersonal behaviour while downplaying the political ends a ‘horizontal’ movement should be trying to establish. From this perspective, reclaiming public space as an opportunity to hold non-hierarchical public assemblies, where we can hammer out decisions by consensus, is, in itself, ‘anarchist’ – whatever the result of such processes.

This has little to do with the classical, mass-anarchist tradition and its politics of revolutionary socialism. It is, instead, an approach which is better described as falling under the banner of ‘neo-anarchism’ (or ‘small-a anarchism’). Neo-anarchism is a modern conception of anarchism largely informed by the feminist and peace movements of the 70s, the environmental movement of the 80s, the alter-globalisation movement of the 90s, and the Argentinian uprising of 2001; which coined the term horizontalidad (‘horizontalism’) to describe the movement’s rejection of representative democracy, the use of general assemblies to coordinate activity, and converting abandoned or bankrupt factories into cooperative businesses.

Take, for instance, the insistence by neo-anarchists on the use of consensus decision making. Though consensus (or ‘unanimity’, as it was typically called) was sometimes a feature of anarchist political organisations, and often seen as an ideal to work towards through comradely discussion, it was never a fundamental component of the anarchist movement. Anarchists have generally agreed that the appropriate form of decision making depends on the circumstances concerned, and frequently endorsed variations of majoritarian voting; particularly in mass organisations based on commonalities other than close-ideological affinity, such as unions. The focus for anarchists has generally not been the form of decision-making, but instead the principles of free association and solidarity. Furthermore, though anarchists have always stressed the right ofthe minority to be free of the majority’s coercion, it is even more important that the great majority be free of minoritarian rule or sabotage. As Malatesta wrote in his pamphlet Between Peasants: A Dialogue on Anarchy:

everything is done to reach unanimity, and when this is impossible, one would vote and do what the majority wanted, or else put the decision in the hands of a third party who would act as arbitrator, respecting the inviolability of the principles of equality and justice which the society is based on.

In response to the concern over minoritarian sabotage, he continues by asserting that such a situation would

[make it] necessary to take forcible action, because if it is unjust that the majority oppress the minority, it’s no more just that the contrary should happen. And just as the minority have the right of insurrection, so do the majority have the right of defense, or if the word doesn’t offend you, repression.[3]

As for ‘autonomous zones’ and the tactic of reclaiming public spaces (as seen in the Occupy movement) – here we have no connection to anarchism as a revolutionary tradition, and an example of a tactic which has repeatedly shown its inability to extract significant reforms, let alone revolutionise production and destroy the State.

The fundamental limitations of the ‘public occupation’ or ‘autonomous zone’ , and the defeats which have followed from these limitations, have led some former advocates of the strategy to make a notable transition from neo-anarchism to parliamentary politics. Though inexplicable to some outside observers, the change is easily understood when we consider neo-anarchism’s peculiar view of ‘direct democracy’, or ‘horizontally organised spaces’, as the defining characteristic of anarchism, and not a theory of libertarian revolution against the State and capital.

If we accept the idea of anarchism as proposed by the neo-anarchists, there is no fundamental contradiction between anarchism and involvement in parliamentary politics. If the political party is a directly democratic one, composed of social movements, and committed to horizontal interpersonal relations, what difference does it make if the decision made (ideally by consensus) is to campaign for political candidates, or even administer the State?

We have seen this with the so-called ‘Movements of the Squares’ in Europe. Activists who took part in the 15M (or ‘Indignados’) movement in Spain abandoned their dismissal of all politicians (“¡Que no nos representan!” – “They don’t represent us!”) with the formation of Podemos and various other ‘municipalist’ parties.[4]

A similar trajectory was followed by the anthropologist David Graeber towards the end of his life. Graeber – a figurehead of Occupy Wall Street and, prior to that, a participant in the alter-globalisation movement – apparently saw no contradiction between his professed (neo-)anarchism and his efforts to join the British Labour Party in support of Jeremy Corbyn. In particular, Graeber was enthusiastic about the Labour-affiliated organisation Momentum; an outgrowth of the Corbyn leadership campaign, which he argued constituted a unique attempt to fuse a radical social movement with a traditional parliamentary party.[5]

More recently we have witnessed the absurdity of a self-proclaimed ‘libertarian socialist’, Gabriel Boric (who touts his association with Chile’s radical student movement), ascending to the presidency in the aftermath of a militant popular uprising.

The damage caused by these supposedly ‘unique’ attempts to translate the ‘horizontalism’ of neo-anarchism into the party-form – which, in reality, hardly differs from the historic approach offered by Marxists as an alternative to anarchism – has been outlined well elsewhere, and there is no need to go over the details here.[6] It suffices to say that in each case there was bureaucratisation, accomodation with the necessities of administering the capitalist state (or even just campaigning to administer it), and zero empowerment of workers against the bosses.

The reality is that there is no way to fully ‘prefigure’ anarchy and communism through ‘directly democratic’ spaces of ‘autonomy’. Anarchism requires a specific anarchist movement and anarchist practice. Though we must certainly organise ourselves from the bottom up, with a consistent federalist structure, we can not simply bring about our ideal by ‘living anarchisticly’ or relating to one another as ‘horizontally’ as possible. Similarly, the content of anarchism can not be limited to the structure of our movement – its content of revolutionary class struggle must be maintained. To quote Luigi Fabbri:

If anarchism were simply an individual ethic, to be cultivated within oneself, and at the same time adapted in material life to acts and movements in contradiction with it, we could call ourselves anarchists and belong to the most diverse parties; and so many could be called anarchists who, although they are spiritually and intellectually emancipated, are and remain, on practical grounds, our enemies.But anarchism is something else… proletarian and revolutionary, an active participation in the movement for human emancipation, with principles and goals that are egalitarian and libertarian at the same time. The most important part of its program does not consist solely in the dream, which we want to come true, of a society without bosses and without governments, but above all in the libertarian conception of revolution, of revolution against the state and not through the state… [7]

#anarchist movement#autonomous zones#class struggle#criticism and critique#dual power#Elections#horizontality#insurrection#Notes#organization#Red and Black Notes#riots#social change#autonomy#anarchism#revolution#climate crisis#ecology#climate change#resistance#community building#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

I cant find anyone, so i run into the red fog. Look straight in front of me, the cloud glides and rushes into the darkness.

#click for better quality probably.. tribulations of a wide scale post…#song in caption is black rain by sneaker pimps. oh my god please listen.#welcome to hell#welcome to hell film#welcome to hell fanart#w2h#w2h fanart#jonathan combs#sock sowachowski#sockathan#w2h sock#w2h jonathan#note the red spirals!!! i used erica westers actual interpretation of the path to hell from the w2h comic hahahahaaa

432 notes

·

View notes

Text

so you know how zeff says to sanji “you can walk right back into the ocean for all i care” after sanji threatens to walk? yeah i think about that line a lot and specifically the way zeff says back. he doesn’t just say sanji can walk into the ocean, he says he can walk back into the ocean. it’s such a simple distinction but it holds so much meaning because, for all intents and purposes, sanji came from the ocean, from that storm and that rock. that single word signifies that whatever happened before, whatever sanjis life was before, doesn’t matter to zeff and it never will because well, why would it? zeff doesn’t give a damn about his past, for all he cares this kid and responsibility for him was chucked at him by the waves of that storm 9 years ago and that was that. and as for sanji? yeah it’s even more meaningful. in his own words: “13 years ago, vinsmoke sanji escaped the kingdom of germa and died at sea”. vinsmoke sanji died and the person he is now, the one who was shaped by zeffs guidance was born. the sanji we see really did come from the ocean, from a random part of the east blue that carried the ship that took him away from germa. it was because of that ocean and that ship that he was able to live the life he deserved and be the man he was supposed to be.

#sanji and zeff fuck me UP#i love when adopted father/son relationships#side note sanji was definitely the kind who threatened to kill himself all the time when he was 14#just based on his immediate ‘i WILL quit don’t test me’#one piece#one piece live action#black leg sanji#one piece sanji#opla#vinsmoke sanji#red leg zeff#no one can stop me meshing anime and opla together#shout out to reiju as well love her and everything she did for him

629 notes

·

View notes

Text

⠀⠀⠀⊹ ˚⋆𐙚ㅤ﹒ㅤminimalistㅤㅤ✶ㅤㅤheaders

#headers#yellow headers#the last of us#the last of us headers#evangelion#evangelion headers#vagabond#vagabond headers#deftones#deftones headers#berserk#berserk headers#death note#death note headers#red headers#the cure#the cure headers#minimalist#minimalist headers#black headers#aesthetic#aesthetic headers#white headers#blue headers#chainsaw man headers#manga headers#cat headers#anime headers#the 1975 headers#band headers

593 notes

·

View notes

Text

2017 Relics; {Credit}

#visual stim#stim#stimblr#stimboard#stim gifs#gifset#stim gif#my gifs#emo#emo stim#2017#internetcore#black#brown#red#blue#grey#orange#shirt#fashion#cringe#mlp#dan and phil#death note#my little pony#my chemical romance#twenty one pilots#smosh#good mythical morning#youtubers

581 notes

·

View notes

Text

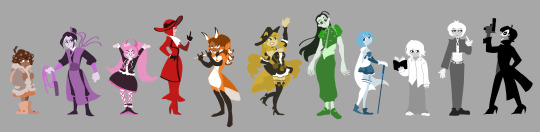

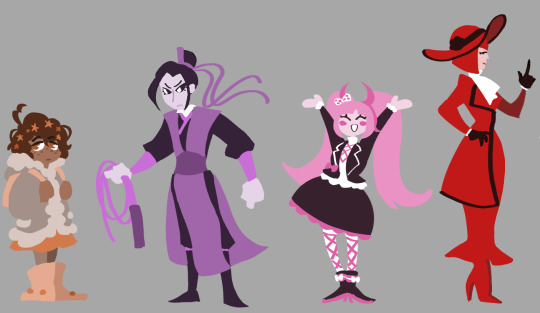

🌈🌈🌈

#oh deep breath everyone this is gonna be a lot of tags#epithet erased#molly blyndeff#mdzs#jiang cheng#danganronpa#kotoko utsugi#black butler#madam red#miraculous ladybug#rena rouge#genshin impact#navia#hxh#illumi zoldyck#madoka magica#sayaka miki#death note#near death note#yttd#ranmaru kageyama#persona 5#p5 joker

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

indivigilantes

hi it’s part 2 where I draw the robins all grown up plus a few extras (everyone say hi babs terry and cass)

#batfam#dick grayson#barbara gordon#jason todd#tim drake#stephanie brown#terry mcginnis#cassandra cain#damian wayne#duke thomas#dc Robin#nightwing#dc oracle#red hood#dc red robin#dc spoiler#batman#batman beyond#batgirl#black bat#dc orphan#dc signal#skartmoree#it’s freakin bats#PLEASE ASK ME ABOUT DESIGN NOTES PLEASE ASK ME ABOUT DESIGN NOTES PL#will make another post to compare the ones that got to be Robin to their prev designs teehee#I learnt how to draw wheelchairs for this! hopefully I did it okay

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mars Dust, Alma Thomas, 1972

Acrylic on canvas 69 ¼ × 57 ⅛ in. (175.9 × 145.1 cm) Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City, NY, USA

#art#painting#alma thomas#contemporary art#abstract art#abstract expressionism#20th century art#20th century#1970s#black artists#women artists#acrylic#red#whitney museum#american#african american#artists of color#female artists#100 notes#250 notes

491 notes

·

View notes

Text

‼️‼️ MISA AND REM 🩸🖋️🖤

#art#artists on tumblr#drawing#digital art#fanart#misa amane#rem#shinigami#death note#rem death note#anime#purple#black#red

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anarchists and Parliamentarianism: Elections and Social Change

There are some who now consider themselves anarchists who tell us, ‘Yes, anarchy is our goal, but we are nowhere near achieving it and have to think about winning desperately needed reforms. That means campaigning for politicians, even running for office ourselves, so that laws can be passed in the interest of the working class.’

There are several problems with this. First, it is important to clarify that anarchism not only entails a belief in the ideal of anarchy – of a society without domination, the State, capitalism, etc. – but a method and theory of social change, based on a specific analysis of existing social relations, processes, and institutions.

Any communist, even the most enthusiastic champion of state power (held in the hands of ‘communists’, of course), can claim the abolition of capitalism and the State as their ‘ultimate goal’. They may even truly believe that their authoritarian tactics are the only ones capable of achieving it. Marx himself conceded that the ideal of anarchy was consistent with his vision of communism, though he advocated electoral politics and some form of ‘transitional revolutionary state’ as the means for doing so. It is important to reiterate, therefore, that what really distinguishes anarchism is not simply the goal, but rather our insistence on a necessary unity between means and ends; of the need to act outside of and against the State, rather than through it.

Equally mistaken is the idea that such a view is only relevant when revolution seems imminent, and that, in the meantime, we should directly involve ourselves in the politics of electoral campaigns, parliaments, and legislation, as these are “the only way to achieve reforms”.

Anarchists reject this understanding of how social change – even reformist social change – occurs. Changes in governments and their policies are driven by the shifting needs of the State and capital, within parameters established by the existing balance of class forces. Reforms are not the product of good or bad ideas, politicians, or legislation, but are, instead, the result of the State serving the best interests of capitalism as a system. Where there is sustained pressure from below, directed against bosses and governments, the ruling class must adjust to the threat posed to profitability and stability. Where naked force is not enough to eliminate the danger of organised working class activity, the threat is pacified through concessions and recuperation.

Electoral and parliamentary victories (including referendums and constituent assemblies) are often touted as flawed, but necessary, culminations of social movement energy into ‘real power’. They should instead be understood as efforts to channel extra-parliamentary activity – the only real power we have – into manageable, legal, and, ultimately, non-threatening forms.

Anyone who seriously examines the historical record will find that it has always been direct struggle, and never legal politics, which has allowed us to achieve reform. As such, anarchists maintain that reform and revolution are the result of the same kind of activity. They cannot be separated, as though one were the natural domain of parliamentary politics, and the other self-organised direct action.

Strikes, sabotage, blockades, civil (and uncivil) disobedience, riots, insurrection: these are not only the tools of revolution, but the sole weapons available to us to change things within capitalism itself. They are also a bridge between the two objectives, reform and revolution, as it is in building our capacity to pressure the bosses and governments that we also develop our forces, our ideas, and our confidence to do away with all forms of oppression and exploitation, which we intend to replace with a free, socialist society.

Electoral campaigns, the day-to-day work of parliamentary bureaucracy, and the exercise of state power are all specific forms of activity which, due to their very nature, distract and pacify workers, diverting us from self-organisation and class struggle. They enmesh us in authoritarian models of organisation and task those who do manage to reach government with maintaining the interests of an exploitative property-owning class, whose interests (given their control over the economic life of society) the State must inevitably serve, and which any government (if it is to continue existing as a government, with the power to govern society as a privileged elite) must always reproduce.

Anarchists believe these tactics necessarily alter the behaviour of those who take part in them, whatever their personal beliefs or intentions. This is not a question of corruption, or betrayal, but rather systemic imperatives and institutional logics which can not be overcome by even the most radical of politicians.

Which brings us back to that principle at the very heart of anarchism: the necessary unity between means and ends. As I have said, this requires that we refuse participation in electoral politics, or the formation of any ‘new’ State, whatever its ‘revolutionary’ pretensions. However, it also means that we must organise, make decisions, and act in ways which both reflect the ideal we are working to establish and directly alter the balance of class forces, without deference to institutions or leaders of any kind. Our organisations must be freely constructed from the rank-and-file upward and our strategic orientation must be toward direct action against the bosses and government.

As a final comment, it is worth noting that this institutional analysis of the State extends to the local or municipal level, and that anarchism can’t be reconciled with such experiments in ‘direct’ or ‘town hall democracy’. Murray Bookchin’s eventual break with anarchism in the late 1990s seems to have been forgotten by ‘anarchists’ who now seek inspiration from his theory of municipalism.[20] His followers mistakenly echo the municipalist belief that the structural imperatives of the capitalist state disappear the closer a governing body is to the population. Unfortunately for the municipalists, the organisational forms of parliamentary politics, the ways in which they alter us as people, and their function within capitalist society, all remain the same at the level of a city council. A localist state-socialism is still state-socialism.

[1] For a critique of what is often mistaken for ‘mutual aid’, see the article ‘Socialism is not charity: why we’re against “mutual aid”’ published by the collective Black Flag Sydney in their magazine Mutiny (available at: blackflagsydney.com). For another examination of how mutual aid relates to Kropotkin’s revolutionary anarchism, see: Gus Breslauer’s ‘Mutual Aid: A Factor of Liberalism’ in Regeneration regenerationmag.org

[2] This quote contains additions made to the 1913 original in a 1914 edition published by Freedom. I am quoting from the definitive 2018 edition edited by Iain McKay, and published by AK Press, but have used the extended text (included by McKay in a footnote) to reflect the longer 1914 version. Available here: usa.anarchistlibraries.net

[3] Malatesta, E. 1884. Between Peasants: A Dialogue on Anarchy. Available at: theanarchistlibrary.org. Malatesta puts forward the same position in his series of dialogues titled At the Cafe (1922). In ‘Dialogue 8’ he writes the following exchange: “AMBROGIO: And if the others [the minority] want to make trouble? GIORGIO: Then… we will defend ourselves.” See: theanarchistlibrary.org.

[4] See Mark Bray’s ‘Horizontalism: Anarchism, Power and the State’, published as a chapter in the 2018 collection Anarchism: A Conceptual Approach. Bray’s chapter is available at: blackrosefed.org.

[5] Graeber was also one of the most prominent advocates of the Rojava Revolution, the specifics of which are too complex to examine in detail here. It must be said, however, that his uncritical lauding of a revolution which (all the available evidence indicates) has formed a state, and purposefully maintained class divisions, indicates the same kind of drift in his political thinking. This drift appears to be rooted in a framework which sees a libertarian legitimacy in all outcomes which can (at least plausibly) be said to have been born out of ‘direct’ or ‘assembly-based’ democracy. For a valuable resource on the Rojava Revolution, which describes the movement’s opposition to expropriation and gradual transfer of power from a rudimentary council system (the ‘People’s Council of West Kurdistan’, or MGRK) to a parliamentary one (the ‘Democratic Autonomous Administrations’, or DAAs), see the 2016 book Revolution in Rojava: Democratic Autonomy and Women’s Liberation in Syrian Kurdistan. Available at: theanarchistlibrary.org. This is an important book given it is the most positive account of the revolution in print (the picture painted should be taken with a grain of salt), features an introduction from Graber himself, and yet concedes these crucial points regarding Rojava’s parliamentary system and the leaderships opposition to the socialisation of property.

[6] For an analysis of Spain, see ‘What went wrong for the municipalists in Spain?’ by Peter Gelderloos in Roar magazine: roarmag.org. For a critique of the Corbyn project, including Momentum, see ‘Labour defeat – Thoughts on democratic socialism’ by the Angry Workers of the World collective, based on a chapter from their excellent book Class Power on Zero Hours (2020): www.angryworkers.org.

[7] Fabbri, L. 1921. Dittatura e Rivoluzione. Fabbri’s book has yet to be published in English. The chapter referenced here (‘The Anarchist Concept of the Revolution’) has, however, been translated by João Black, with assistance from myself. It can be read here: theanarchistlibrary.org.

[8] For an introduction to the ideas of dual organisationalism, platformism, and especifismo, see Tommy Lawson’s pamphlet ‘Foundational Concepts of the Specific Anarchist Organisation’, published by Red and Black Notes: www.redblacknotes.com. I also highly recommend Felipe Corrêa’s essays ‘Organizational Issues Within Anarchism’ (2010, Espaço Livre), available here: theanarchistlibrary.org, and ‘Bakunin, Malatesta and the Platform Debate: The question of anarchist political organization’ (2015, Institute for Anarchist Theory and History), co-written with Rafael Viana da Silva, and available here: theanarchistlibrary.org.

[9] This was often sold by governments and union leaders as a sacrifice necessary to resolve the economic crises of the period. It also supposedly offered the movement “a seat at the table”, or a “share in power”. In reality, the crisis was one of profitability, which could only end with the crushing of the labour movement, or a social revolution. By sacrificing the ability to take direct action for an illusory idea of power within the State, the labour movement accepted its own disorganisation and a major defeat. For an excellent study of this process as it occurred within Australia, through the form of ‘The Accord’, see Elizabeth Humphrys’ 2018 book How Labour Built Neoliberalism.

[10] “We have seen that the specific minority must take charge of the initial attack, surprising power and determining a situation of confusion which could put the forces of repression into difficulty and make the exploited masses reflect upon whether to intervene or not.” – Bonanno, A. M. 1982. ‘Why Insurrection?’. Insurrection. Available at: theanarchistlibrary.org

[11] For a comradely critique of the CHAZ (or ‘CHOP’) project, see the analysis written by Black Rose Anarchist Federation members Glimmers of Hope, Failures of the Left: blackrosefed.org. Perhaps even more interesting is the critical account from the CrimethInc collective, The Cop-Free Zone: Reflections from Experiments in Autonomy around the US: crimethinc.com. Indeed, CrimethInc appears to be a collective in a period of transition. Once the favourite of dumpster-divers and purveyors of ‘riot porn’, they have increasingly become a reasonably reliable source for breaking news of working class uprisings around the world. They have even begun to engage more seriously with classical mass-anarchist history and theory, as in their great 2019 essay Against the Logic of the Guillotine: crimethinc.com.

[12] Idris Robinson’s essay ‘How It Might Should Be Done’ (originally a talk; later published by Ill Will Editions) is justly scathing on this phenomenon: There’s a lot of talk about how to end racism, especially within corporate and academic circles. We saw how to end racism in the streets the first weeks after George Floyd was murdered. “It was only after the uprising began to slow down and exhaust itself that the gravediggers and vampires of the revolution began to reinstate racial lines and impose a new order on the uprising. The most subtle version of this comes from the activists themselves. Our worst enemies are always closest to us. You’ve all been in these marches, these ridiculous marches, where it’s, “white people to the front, black people to the center”—this is just another way of reimposing these lines in a more sophisticated way. What we should be aiming for is what we saw in the first days, when these very boundaries began to dissolve.” Robinson’s essay can be read here: illwill.com. Another essay by Shemon Salam, ‘The Rise of Black Counter-Insurgency’ (also published by Ill Will) touches on similar issues and is likewise recommended: illwill.com.

[13] One can’t help but recall the uncritical enthusiasm demonstrated by many insurrectionary anarchists during the 2014 Euromaidan uprising in Ukraine. Not only was there little interest in the political character of the struggle, but even in the influential presence of far-right elements. People were in the streets, in violent conflict with the brutality of the State… Molotovs were being thrown! ‘What else is there to a revolution?’ This is how an ‘anarchist’ thinks when they are not concerned with class struggle and the need to transform the structures of production and distribution.

[14] Salam, S. Breonna Taylor and the Limits of Riots’. Spirit of May 28. Available at: www.sm28.org. Salam’s argument recalls similar points made by Malatesta. See, for instance, his articles ‘The Products of Soil and Industry: An Anarchist Concern’ (El Productor, 1891, available at: theanarchistlibrary.org) and ‘On ‘Anarchist Revisionism’’ (Pensiero e Volontà, 1924, available at: theanarchistlibrary.org).

[15] Leoni, T. 2019. Sur les Gilets Jaunes. Translation is from Gilles Dauvé’s equally important piece for troploin, ‘Yellow, Red, Tricolour, or: Class & People’. For Dauvé’s essay see: www.troploin.fr. Leoni’s work is available in French here: ddt21.noblogs.org

[16] All quotes from Bonanno, A. M. 1977. Armed Joy. Available here: theanarchistlibrary.org.

[17] This is true whether we are concerned with unions or (Bonanno cannot avoid this!) ‘federations of production nuclei’.

[18] All quotes from Bonanno A. M. 1975. ‘A Critique of Syndicalist Methods’. Anarchismo. Available at: archive.elephanteditions.net.

[19] Or ‘synthesis organisation’ as Bonanno confusingly calls it. Typically, synthesis organisation refers to an approach in which anarchists of all types work together, without a specific shared analysis, programme, or strategic approach.

[20] For a good critique of Bookchin’s break with anarchism, see Iain McKay’s review of The Next Revolution (2015): robertgraham.wordpress.com.

#anarchist movement#autonomous zones#class struggle#criticism and critique#dual power#Elections#horizontality#insurrection#Notes#organization#Red and Black Notes#riots#social change#autonomy#anarchism#revolution#climate crisis#ecology#climate change#resistance#community building#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

in his shadow the hedgehog era ❤️

#superboy#kon el#dc comics#artists on tumblr#my art#conner kent#ngl the red hair caught me off guard at first- but its fun#red on both sides of the part?? the black curl in the middle?? why would he do this????? fantastic- no notes#not a fan of the new pairing :(

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Bed :3

#goth#mall goth#gothic#emo#emily the strange#emilythestrange#ruby gloom#rubygloom#skelanimals#korn#hello kitty#death note#goth room#gothic room#maximalist#clutter core#pillow collection#pillows#red and black#goth bedroom#goth bed

468 notes

·

View notes

Text

i’m sick again but at least i have nintendo 3DS notes app at the doctor’s office for emotional support

#very convenient that black red and blue are like the only colours you need to draw them#they’re kind of ugly but it’s Okay. i lowkey like drawing on Notes 3DS. it’s cute#sketches#pokemon#submas#ingo#emmet

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apprentice Arin outfit idea...

#he got the dark red jacket w gold for imperium ras#the black and pink r meqant to be ras colors#the red is for strength#the dark blue and gold r the only colors arin casn keep from who he Was#note hes not Evil hes just . ras' student now .#ninjago#ninjago dragons rising#ninjago spoilers#ninjago art#raine's art#arin ninjago#ninjago arin

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

I met the devil by the window 𓉸ྀི ִֶָ . 𓂃 ࣪ ִֶָ🍷་༘ ♱

@yawnznn 🖤

#yuqi-luv#divider by anitalenia#yeonjun#txt#yeonjun txt#txt devil by the window#kpop#kpop moodboard#yeonjun moodboard#txt moodboard#bg icons#txt icons#yeonjun icons#black moodboard#dark red moodboard#red moodboard#grey moodboard#dark moodboard#vampire moodboard#gothic moodboard#grunge moodboard#alternative moodboard#event prize#200 notes

220 notes

·

View notes

Text

The way they gave him that slutty, slutty crop top and no belly button ring is a literal crime.

#my favorite colors are also red and black he's just like me fr#mello#mihael keehl#death note#death note manga#mello death note

96 notes

·

View notes