#// white collar

Text

Me, reading my scraps of fics in my notes app: oh, that’s good, I really like that. Someone should finish that.

26K notes

·

View notes

Text

Can someone please explain to me why there are 970 crossover fics between batman and white collar on ao3. What is the correlation?? Why is this such a phenomenon???? I had never even heard of this show but now I know like all of the main characters names just from fanfic descriptions. Please someone make it make sense.

#bat fam#bat family#dc#dcu#dc comics#ao3#white collar#neal caffrey#peter burke#bruce wayne#batman#dick grayson#nightwing#jason todd#red hood#tim drake#red robin#damian wayne#robin#briar.txt

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

I am very sleep deprived and this will most likely not be funny anymore once I am not but I’m posting it anyway

(can't believe I have to put this on this post) NS4W blogs do not interact

515 notes

·

View notes

Photo

White Collar 1x1 “Pilot” / 4x10 “Vested Interest”

770 notes

·

View notes

Text

White Collar S01E10

↳ RFW's Favorite White Collar Whump Moments (✚)

#white collar#whumpedit#neal caffrey#peter burke#drugged#vulnerability#handcuffs#ep: vital signs#wc 1x10#oh peter you so got played#though i 100% believe everything neal said was true#favorite white collar moments

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

- White Collar rewatch (121/?) 4x16 In the Wind

#White Collar#Tim DeKay#Matt Bomer#hilarie burton#treat williams#Peter Burke#Neal Caffrey#mozzie#sara ellis#james bennett#white collar rewatch#my gifs#that episode started so lighthearted... then proceeded to crush my heart#still not over it 10 years later

471 notes

·

View notes

Text

White Collar 1.08 - Neal Caffrey

380 notes

·

View notes

Text

oh yeah...its all starting to fall into place

an addition to the original post

#look ik top left couldve easily been robin hood but like#sly cooper's family lineage of thieves and overall niche feels a lot more like lupin ok#he just seems like a more balanced combination of nick and lupin's traits and styles#im also not super satisfied with putting fantastic mr fox in the top right#bc i think it could be argued that mr fox could fit just as well in the middle as mr wolf does#but i couldnt think of anyone else who would fit there as easily and as obviously he does#lupin the third#lupin iii#lupin the 3rd#Arsene Lupin III#neal caffrey#white collar#danny ocean#ocean's 11#oceans 11#oceans eleven#oceans trilogy#nick wilde#zootopia#fantastic mr fox#fantastic mr. fox#mr wolf#mr. wolf#the bad guys 2022#the bad guys#sly cooper#im also willing to further elaborate on this to anyone who asks

824 notes

·

View notes

Text

its absolutely criminal that white collar is not more universally known and beloved given the sheer density of Truly Iconic trope-based episodes it has. the episode where the fbi agent gets kidnapped and the thief has to rescue him is followed immediately by the episode where, through whacky hijinks, the fbi agent and the thief have to assume each others identities and do each others jobs. im gonna throw up ❤

563 notes

·

View notes

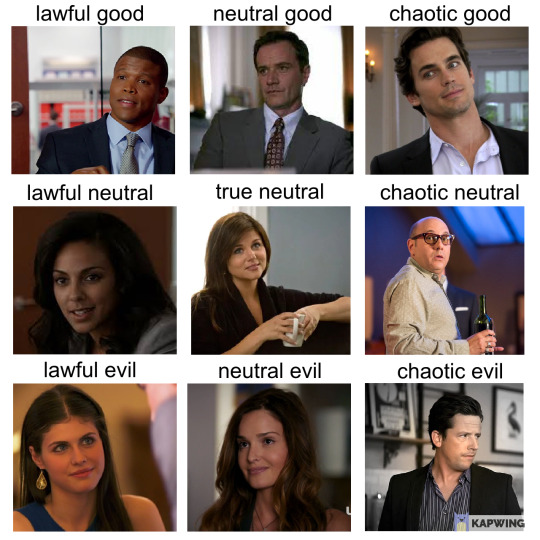

Photo

#white collar#Matt Bomer#Tim DeKay#Willie Garson#Alexandra Daddario#alignment chart#Tiffani Thiessen#Marsha Thomason#Sharif Atkins#Ross McCall#Gloria Votsis#Neal Caffrey#Peter Burke

633 notes

·

View notes

Text

neal caffrey, you deserved better

#i’m having this conversation about white collar and fuck#i forgot how basically all of neal’s relationships are based on how useful he is#i’m so sad now#neal caffrey#white collar

198 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marbles

Summary: Ellen isn't the only person who knew Neal Caffrey before he became Neal Caffrey.

Word Count: 7,333

Requested by anonymous; photo credit is Jeff Eastin's Twitter

St. Louis, 1984

Kids at school called you Marbles because you always had a little bag of them with you. You knew even then that the nickname was supposed to be mean, but it had never gotten under your skin. You just laughed along, because, yeah, it was kinda weird that you carried marbles, but you played with them all the time and loved it. And before long, they were calling you Marbles because it stuck, not because they were laughing at you.

Marbles were just great fun. And in second grade, whenever you had extra time, your teacher would let you play with them and a classmate or two so long as your other work was already done. After a couple of weeks into the school year, you had a few people you would regularly play with. Danny was one of them. His bright blue eyes made him stand out from the boys at his table. He was cute, but at seven, you still preferred puppies to boys.

The first day he talked to you, you’d been bouncing some marbles on the carpeted floor to stay quiet, staring at them intently and trying to devise a new game in your head. Danny sat cross-legged and asked if he could play. Abandoning your half-baked game, you reached up to your desk and grabbed a piece of paper from your class folder, quickly drew the circles to represent a mancala board, and divided the marbles. Danny beat you on his first try. That was when you knew you liked him. You gave him a bag of your marbles so he could make new games, too.

From then on, you played together whenever you could, but scarcely stuck with one game for very long. You were both easily bored by the simple games that marbles allowed, so you fiddled with the rules, tampering with the game play to see what would happen. Sometimes you created entirely new games, sometimes incorporating other tools that were easy to carry in school or to the park, like a set of dice or an origami fortune teller.

By Christmas that same year, you’d started to exhaust your options and branched out into other ways of entertaining yourselves. Cards were good for quick games, and the randomness of a good shuffle kept games interesting for longer. Puzzles were great for you both, but they took too long to do at school and you could only play them when you had a playdate or sleepover. Eventually, you settled on codes and ciphers as your mutual favorite activity. You could create them when you were together and have secret communications, or you could create them separately and challenge each other to solve them. You liked to base yours on symbols and books. Danny liked incorporating math. By the end of the school year, you had a collection of codes of varying complexity.

St. Louis, 1986

After nearly two years of friendship, you and Danny snuck downstairs to his aunt Ellen’s TV to watch a new movie. It was called The Color of Money. With a shelf of adult movies in front of you, you were way more interested in the popular titles you recognized, like Ferris Bueller and Top Gun, but Danny convinced you to give Scorsese a try and you never regretted it. That movie introduced you two to the world of gambling. As cynical nine-year-olds, you weren’t really interested in the idea of gambling so much as the behavior of people who did it – and the methods behind milking out the most rewards for the least risks.

It took some needling and permission from your parents, but Ellen finally agreed to teach you both how to play poker. One Friday, she picked you both up from school, took you to the store to pick out a box of your favorite candies, and used the chocolates in place of money. With bowls of candy at stake, you learned what cards you wanted, when to fold, and how to count the multicolored plastic poker chips. Initially, Ellen hadn’t wanted to teach you to bluff on principle of not encouraging children to lie, but they had bluffed in all the movies, so you and Danny both tried it without her suggestion. She was exasperated, but amused by your complete failure. Danny had much better results, and when Ellen went to bed and left you to either play cards or watch a movie, he told you that when you lied, you always lifted your chin, like you were daring someone to call you on it.

You both had detention the next week for trying to use poker to win your classmates’ brownies at lunch.

St. Louis, 1989

When you were twelve, Nintendo came out with the Game Boy. Neither of your families had the kind of money to spend on a game system like that, so you and Danny decided you could team up to buy one for yourselves to trade back and forth. It was better to have the hot new thing sooner than later, even if it meant taking turns. You took out a sheet of paper to figure out how long it would take if you pooled your money together; even with the little bit of spare allowances you had socked away, you both still needed to save over thirty dollars each.

In hindsight, what happened next was probably your parents’ first red flag.

Sixty-four bucks, for a couple of kids in the late eighties, was a lot of money, and you were both too young to legally get jobs. Divide and conquer, however, had already demonstrated merit when it came to convincing your parents of letting you go to the fair or the movies, so why not divide and conquer to raise cash? All you needed was enough people contributing. But then came the problem that if they contributed, they’d feel entitled to your Game Boy. It was for the two of you, not anyone else. So they would need to be paid back by money you got from somewhere else.

To summarize a long story, and explain many angry phone calls from your peers’ parents, you and Danny essentially ran a pyramid scheme to raise the money for a Game Boy, enticing kids in your old elementary school to pay forward their allowance to your first- and second-round financiers in your middle school. When you were caught, you were grounded for months – but by this point, you were both well-practiced at sneaking between each other’s houses and hiding things in your rooms, and you had a Game Boy.

Your parents’ anger and the way your little sister’s friends’ parents treated you made you realize you’d done something morally wrong. It was humiliating and shameful to be looked at that way. Danny didn’t take it as hard as you did. It rolled off his back once Ellen was back to treating him the way she always had. Danny needed to be liked, and he was liked a lot, because he was cute, and smart, and didn’t bully girls at school, and now he had a Game Boy, so he didn’t mind that kids in a different school and their parents he never saw thought badly of him. It didn’t affect him day to day the way that the guilt started to carve into your self-esteem.

In hindsight, that was your first red flag that there was something a little bit off about Danny. When you brought it up to him, he genuinely didn’t see why you felt so bad. You hadn’t lied to those little kids, and after all, each one only sacrified a couple of dollars. You couldn’t articulate just why, but you needed to make it right. In the end, Danny helped you make it up to the kids by handing back out a portion of your allowances for a few weeks and helping out with their homework, but you knew he’d only done it because he was sad to see you so upset.

You couldn’t deny how great it had felt to accomplish something so quickly, and Danny had boasted for weeks about how persuasive he’d been, but you made an agreement that from then on you wouldn’t hustle kids anymore. Danny pouted about it a little because they were such easy marks, but he agreed to keep you happy. When your wrongs were righted, you felt restored, and you got back to your regular mischief – but you were much more cautious of whether you were being clever or just unethical.

St. Louis, 1992

High school was an entirely different beast from middle school. You and Danny kept sending each other coded letters and hanging out on the weekends, but he was the one who got caught up in how girls looked twice at him and how guys wanted to be his friend. Danny joined the cross-country team, partly to spend more time with those friends and partly to keep in shape to apply for the police academy after high school, and started to pursue girls. He had a new girlfriend every other month. And it meant, altogether, that there was less time for you – so you followed his lead and joined your own clubs, made your own friends.

In freshman year, there had been a rumor that you were dating. You’d loudly opposed it. You had eyes and could see that he was hot, and you didn’t think you’d ever be happy with anyone less smart, or less kind to you, but the idea of kissing Danny just made your stomach turn. There was one time when he started dating a cheerleader who made the mistake of threatening to “ruin” you if you didn’t back off of “her” Danny – he dumped her as soon as you told him what happened. So, although you didn’t have as much time to spend with each other, there was never any doubt that you were still best friends.

You still liked friendly competitions, and found ways to work together to make quick money or convince your parents that what you wanted to do or see was a good idea. But something about high school flipped a switch in Danny. Maybe it was all the teachers saying now was the time to shape up. Suddenly, everything he did was in light of being like his father. Danny had always idolized his dead dad, and you couldn’t bring yourself to criticize him for that, even when it made him sort of a buzzkill. Did he really think that none of the city cops had ever snuck some liquor from their mom’s freezer? And goodbye to any manipulative schemes – even if your conscience hadn’t stopped you, Danny’s ambitions would have. He still had no moral compunctions about taking from people who didn’t need what they had, but for the fact that it was illegal and could jeopardize his future as a cop.

“Cop this, cop that,” you complained once, playfully shoving at his arm. “Am I gonna have to become a criminal to force you to loosen up?”

“You wouldn’t dare,” Danny responded with absolute confidence. “You wouldn’t like prison.”

You’d scoffed. “You’d turn in your best friend?!”

He gave you a cheeky grin. “If my best friend’s not smart enough to get away with crimes, she shouldn’t be committing them.”

St. Louis, 1995

You weren’t sure what you wanted to do after high school. Your parents were supportive of whatever you wanted to do, but they hoped you’d at least give college a try; but without any idea what you wanted to actually do, you couldn’t justify spending that much money on it to yourself. The more you thought about what you really loved to do, you kept coming back to games and puzzles. It had been years since anyone called you Marbles, but the passion that bonded you and Danny had persisted.

It was when you were watching the new Will Smith detective movie that you realized maybe you and Danny had this in common, too. He wasn’t just going to be a great cop because of his father; it was because he had a knack for solving puzzles. Maybe investigating was your great calling in life. How cool would it be to be detectives together??

You sat on it for a few weeks, thinking it over before telling Danny you were going to apply, too. That way he wouldn’t know to be disappointed if you changed your mind. In the end, you never did get to tell him. You were still thinking about in by his eighteenth birthday.

You’d already agreed to go to the mall together so you could buy him dinner, but he never came to get you like he’d said he would. You called his home, but no one picked up, so you called his aunt’s neighboring house instead. Ellen had answered and tiredly said that it wasn’t a good time. Assuming they’d had a fight, you let it be and minded your business, changing your plans when it became clear that the mall was off.

The next morning, you left to go get him before walking to school, just to make sure he was feeling okay. He and Ellen rarely fought; Danny tried so hard to be on his best behavior for her, even before he’d straightened up to make sure he got into the police force. You noticed the post on your mailbox was up and detoured, and took out a piece of folded paper. No envelope and no stamp – just your name on one of the trifolds.

Assuming it was another coded letter, you eagerly unfolded it to see what kind of patterns you were working with and mull it over on the way to school. To your disappointment, it was plain English. And, to your horror, it was an apologetic goodbye note.

You sprinted several streets away to the Brooks house and pounded on the door. No one answered. You were almost panicking, considering grabbing the extra key Danny had told you about, before Ellen next door caught your eye, waving for you to come over. You jumped off the porch and ran in, dumping your backpack by the doorway to show her the note. The blonde woman barely glanced at it before saying, “I know. I’m so sorry, Y/N.”

It was surprising how clearly you could remember that moment all these years later, especially when what came next felt like a blur of colors and motions melting together. You think Ellen sat you on her couch and poured you some tea. She made you sit and breathe before she explained to you that she’d caught Danny – Neal – signing an application for the police. He was so eager to do it the moment he’d turned eighteen, that Ellen hadn’t had a choice. She’d had to tell him he couldn’t, because Danny Brooks wasn’t his real name; and even if it were, he needed to know that his motivation, the story he’d been telling himself for years, was a lie.

Ellen told you that the Brooks family were actually in Wit-Sec. That Danny’s real name was Neal Bennett, and that his father had been a cop, but a dirty one. That Ellen wasn’t really his aunt, but his corrupt dad’s police partner, who had testified against him and asked to be relocated near Neal, just to make sure the little boy grew up safely. That Neal had been too young to remember. That he had run away, and she didn’t think he was coming back.

Ellen – you still didn’t know if that was even her real name – let you sit on her couch for hours, staring at the floor, drinking the tea she poured mindlessly after it had gone cold, and crying with grief. It was the one and only time she’d ever condoned playing hooky from school. She rubbed your back for a little while, and then let you sit in silent shock while she went about cleaning. It took you an embarrassingly long time to realize that she wasn’t just cleaning, she was packing. Packing to leave. Because people were going to wonder why Neal had disappeared, and maybe the cops would get involved, and maybe her and Neal’s mother would both be in jeopardy.

Ellen gave you a small box of Neal’s belongings that she thought you’d want. In the bottom was the bag of marbles you’d given him in second grade.

Life was never the same after Neal left. Your best friend was gone. You figured, hey, he’d always been street-smart, the odds were pretty good that he was still alive; but the way he disappeared, the odds were also pretty good that you would never see him again, so to you, he may as well be dead. You thought of him sometimes (often) and hoped he was okay, when you weren’t wishing he would come home or cursing his fake name for making you care and then abandoning you without the decency to say goodbye to your face.

You had so many questions in the coming weeks, but the day after Neal had vanished, so had Neal’s not-aunt, along with any opportunities for closure. Once, a few days later, you scraped up the guts to use that hidden key he’d showed you and let yourself into his and his mom’s house. It was completely empty, but left in disarray, with scraped paint, peeling wallpaper, dust settled deep in the rug corners. It had been a long time since you’d spent time together there, rather than in Ellen’s, and now you knew why. With hindsight, and a psychology degree, you were reasonably sure that Neal’s mother had been fighting depression his whole life, and most of the house felt the same.

To make it worse, Danny had been such a beloved part of the school community that in the two months between his disappearance and your graduation, everything under the sun passed under the rumor mill. At first the cops investigated. They talked to you, interrogated you. One of them made you cry by insinuating you were secretly in love with him, and killed him because he’d been dating some chick on the track team. Another rubbed your shoulder and offered you cocoa because he “couldn’t possibly imagine how cofused you’re feeling”. And the whole time, you felt compelled to lie, choking on your tongue and stumbling through how he missed your plans on his birthday and left a note the next morning. You left out the part where you’d talked to Ellen, because what the hell were you supposed to do? Out her as a witness? Admit that Danny Brooks was such a deep lie that even he hadn’t known about it?

Whatever the correct procedure was, no one had bothered to tell you about it. But you were reasonably certain that whoever was in charge of securing the Bennetts, and Ellen, they had caught wind of the investigation, because rather suddenly, all the police activity stopped. You were left alone, and so was his girlfriend, and the guys he played soccer with. The only way they would drop a missing persons case that hard and that quick was if the feds stepped in and told them to back off.

Your parents, and even your little sister, knew that something was off about you. You’re reasonably sure that your entire family knew you knew something you weren’t sharing. But after weeks of trying to comfort you and get you to open up, they started to let go, trusting that if you knew anything actionable, you would have shared to protect your friend.

The police letting it go didn’t end the nightmare for you, though, because the talk at school continued. The US Marshals couldn’t tell everyone to shut up and mind their business. Some people thought Danny had run away from his mother, others thought he’d been kidnapped and trafficked. Some thought he’d knocked up a girl and they ran away, but that one ended when the girl came back to school, and it turned out she’d had the flu. Some people thought you must have had something to do with it, because you’d been so close for so many years. Those people really got to you, because in truth, you could hardly believe you’d known the boy for most of your lives and never suspected he was anything else.

March trudged into April and April slipped into May, and your graduation crawled closer. You were announced as valedictorian. When you went to get the honors sash to wear over your gown, the administrator compassionately told you that Neal would have been valedictorian, had he been there, so though they knew it must be hard, you should keep your head up and be proud enough for the both of you. That just made it even harder to get through. What was supposed to be one of the best days of your life was one of the darkest. A huge shared milestone was lonely. Neal had run away, left you picking up the pieces in a shattered social circle, and now you were taking his place, and somehow someone else had figured out he had that tiny edge over your GPA, and a picture of you in your cap and gown giving your speech was put on a blog along with an accusation that you killed him or threatened him away so you could be valedictorian.

You had to get the hell away. Every unnecessary second you spent in your neighborhood, in your school, in the city you used to share felt like it was scratching at your skin. The application cycle for colleges was long closed, but you took your savings, promised to call your parents every day, and moved to California, as far away as you could get. There, you got a job, found a shitty apartment to share with a girl who minded her own business, and scraped by until you could apply to college.

Palo Alto, 1999

High school valedictorian had felt like a hollow and bitter loss more than anything, rubbing salt in the wound that Neal was gone. In the four years of college since, you’d made plenty of friendly acquaintances, and even some good friends, but none as good as Neal.

You’d visited the school counselor a few times. Told her, minus what you knew about Neal and Wit-Sec, what had happened to drive you all the way from St. Louis to Palo Alto for school. She’d been incredibly sympathetic, even as she suggested that perhaps there had been some trauma mixed in with the grief. Looking back, you could accept it for what it was. You lost your best friend, on multiple levels, and then members of your community turned on you, accusing you of the worst. And, though you were still the only one who knew, the whole time you’d been holding onto a secret boring through your soul that you couldn’t share with anyone.

College graduation felt… much different. Like a success. You were proud of yourself. Sad to see it go but happy you’d made it out the other side, not just of a program but of the grief that had clenched you so tightly. This was what graduation was supposed to feel like. You weren’t valedictorian – or whatever the university equivalent was – this time, but you were graduating with honors, and had an acceptance to a graduate program in hand, so there was that.

Your whole family made the trip to see you graduate. As you walked across that stage, receiving a piece of paper bound in ribbon, you wished once again that Neal would’ve been there to celebrate with you, and hoped that he was okay, then found your family in the crowd and beamed at them brightly, tears pricking in your eyes with joy. Your sister was doing her best to be both supportive and embarrassing by wearing an obnoxiously neon shirt with your name on it.

You faltered in your steps across the stage, just for a second, when you saw the face in the crowd grinning from behind your father. They were so far away, it was kind of hard to see, but for just a second, you could’ve sworn…

You got nudged from behind and had to look down to safely get off of the stage steps. When you were out of the way of the procession, you looked for your family again and stood on your toes to see around your parents. The face you thought you’d seen was gone. You looked down to the rolled paper in your hand, proclaiming you’d earned a bachelor’s degree in psychology, and shook your head; you, of all people, should know the power of wishful thinking.

Your parents took you back by your apartment to change out of your regalia before going for a celebratory meal. You hurried up the steps in your dress heels, eager to get out of the heavy robe, but stopped cold just on entering the front door. Sitting on the cheap kitchen table was a bouquet of flowers and a little bag of marbles.

Your gut response was to clear the apartment like they did in the cop movies, but you didn’t have a gun or a taser or even pepper spray, so if you searched and found someone, you were really just putting yourself in more danger. Cautiously, you inched towards the table, along the way recognizing the flowers as the kind that you used to admire while walking to school. When no one jumped, and you didn’t feel unsafe getting closer to the table, you slowly picked up the bag of marbles. The little beads clinked together. You held them up for inspection and realized that they were color tinted, but still mostly translucent, and inside each was a clay creature. Your favorite animal, sculpted and suspended in resin.

No one had given you marbles, or called you by that name, in years. You hadn’t carried them anywhere since middle school. And you certainly couldn’t have told anyone what your favorite flowers were when you didn’t even remember what they were called.

The marbles, the flowers, and the face you thought you’d seen at the ceremony all added up to mean one thing to you, and instead of changing your clothes, you sat at the table with the marbles in your hand and had a good, solid cry for a few minutes. Then you stored your new marbles with shaking hands in your so-called Neal Box and put the flowers in some water. You couldn’t decide if you were happy, sad, or furious, but it all boiled down to one thing: he was alive. And still thought about you, just like you still thought of him. And that was something to celebrate, even if your family didn’t know it wasn’t just your graduation that you were happily crying over.

Quantico, 2001

Completing your Master’s degree was your new proudest achievement, but though there wasn’t anything bad about that graduation, when you walked the stage, you’d hoped to catch another glimpse of a familiar face. No such luck. You still weren’t too worried. Ever since getting those beautiful marbles, you’d gotten an anonymous postcard every once in a while. There was usually a little note on them in one of your oldest, simplest ciphers. Nothing complex, but enough to let you know that he was okay, and he was thinking of you.

Sometimes you wondered why he didn’t ever just come say hello if he missed you. Yes, you were a part of Danny Brooks’ history. But if Neal Bennett had had to reinvent himself out of a lie, did that have to mean shunning everything about who he’d been?

Still, a note once in a while was better than the four-plus years you spent with radio silence, hoping he was alive, knowing it was even probable, but with no proof and no way of verifying.

Shortly out of your Master’s program, you were accepted into the FBI. A couple of internships during school had showed you that you weren’t interested in clinical practice, nor did you think you really had the drive to push through a doctorate program, so you looked for ways you could use your degrees to solve puzzles, returning to that lifelong passion for an intelligent challenge. You found the bureau, and other members of the alphabet soup, but especially the bureau. It was probationary, but you were in, and it was time to head to Quantico.

The physical exercises were draining. You’d never been so active in your life. Still, the mental exercises were more entertaining than not, so long as they didn’t get so repetitive. Your very favorite instructor took the class of recruits through prolific cases that hadn’t quite become public knowledge, or cold cases that still had yet to be solved. Unlike a documentary, instead of telling you step-by-step what had happened, he prompted and prodded at the agents in training to work their way through themselves. You excelled at this exercise and it proved to you that, although you’d have to work hard to secure a role where you could choose to work on these types of cases, the opportunity was there. That was what you wanted to work towards.

At least, it was your favorite class. Your emotions changed the day that you were shown pictures of inductees into the FBI’s Most Wanted ranks. Because, to your horror, you recognized one of those faces. He was six years older, but there was no chance you wouldn’t have recognized him. Not him.

“Not him,” you nearly whispered out loud, barely catching yourself before your tongue moved in your mouth. You drank in all the information they had on him – suspected of bond forgery, along with a litany of other crimes, and dubbed James Bonds, because they had no clue what his real name was.

You had a split second choice to make, and you felt the pressure beating down on you. Either betray your best friend and turn him in to the FBI, or betray the moral conscience you’d long since sworn to live by – along with the bureau you were about to swear to serve.

It was an easier choice than it should have been. It would haunt you, but you couldn’t fathom for a second turning your back on him. For as long as you stared at the list of things he was wanted for, there was nothing in that list that could make you hate the man he’d become.

The instructor had noticed you stopped at Neal’s image. “Is there a problem?” He asked you expectantly.

Shit. Every game of poker with Neal came to mind and you controlled all the tells he had ever warned you of, making your decision and committing to it. “No,” you said, looking up and putting on your best amused face. “Sorry, Sir. It’s just… James Bonds?”

You sold it so well that you should’ve been ashamed. The senior agent chuckled and shook his head a bit. “I guess the opportunity felt too good to pass on,” he said, picking up the flyers from your row to share with the next group.

Quantico, 2003

You weren’t capable of turning on Neal, but you also couldn’t bring yourself to follow his case. The conflict of interest was too strong in your gut, so you just turned a blind eye to any flyer you saw, or a deaf ear to any curious chatter about James Bonds and his globetrotting stunts.

You kept an eye out for postcards and anonymous letters, but they’d become less frequent. Either Neal had been keeping tabs and learned you joined the bureau, or he’d realized sending mail was becoming more hazardous. In either case, you still got some once in a while, so if it were the former, he was trusting you.

Over the years, the more you heard about him, the more impressed you were. But also the more… saddened you became. Neal had strayed so far from the man he had wanted to be when you’d spent so much time together. You had to wonder if he were truly happy. At this point, his face was plastered anywhere law enforcement could be assed to look, and you had to hope that he was, because you feared it was too late for him to change course, even if he wanted to.

At some point, you’d begun to realize that you were technically aiding him just by keeping in touch. You didn’t have a way to send messages to him, but however he’d found your address repeatedly, he really was trusting you – it took over a year, but between bits you overheard and images on postcards, you realized that he was actively sending you clues as to where he was. Now, you doubted that he was doing so with that actual intention. More likely, he was just sending you the postcards because he knew you’d always liked their pictures and wanted to travel. But there was an additional professional boundary being crossed when you knew that the agent in charge of his case was searching for him in Germany or Iceland when you’d just gotten a card from Cape Town or Tehran.

It also occurred to you that he wouldn’t be an anonymous James Bonds forever. Sooner or later they would figure out who he was. They’d trace him back to either Neal Bennett or Danny Brooks. Both names would flag with the Marshals, and the FBI would learn all about how he disappeared overnight from St. Louis. The FBI would also learn all about how the police had questioned his best friend, Y/N Y/L/N, for days. And then they would have a lot of uncomfortable questions for you that you still had no idea how you were going to answer.

Then, one day, James Bonds had a name. Neal Caffrey. You didn’t recognize his last name, but it was instantly committed to your memory. Now you knew what he was going by. It was another hit to your heart. He didn’t keep either of his last names. But he had kept his birth name – which had been foreign to him when he learned what it was. It was hard to tell what was going on in his head. You hoped he knew what he was doing. And you hoped that whatever he was choosing, he was happy and safe.

From the moment he’d been named, you kept waiting for the agents you worked with to turn on you, ask you those awkward questions, but the time never seemed to come. For a second, you had considered running, but you didn’t have the knowledge or connections to get very far or hide for very long. No, the best option for you would be to bow your head and accept the consequences. But those consequences didn’t come for you, and when you saw the updated flyer, you saw why. They had him listed as born in Texas during February. The bureau had a whole fake identity that they fully believed; they had no idea who he really was.

“You astound me every time,” you’d muttered to yourself, closing the browser window.

Ossining, 2005

If you ask someone where Sing Sing is, they’ll probably just say “New York”. If pressed, they might even say “New York City”. Very rarely do they actually realize it’s about thirty miles upstate in a little town called Ossining. You’d never been, and had no reason to go, but when you saw the email memo that Neal Caffrey had been apprehended and was awaiting arraignment, you didn’t think you had much of a choice in the matter. You filed for a transfer, ostensibly for a change in scenery, and fortunately, it was granted. Your new home was New York City.

Your shoes and your conscience itched to guide you upstate straight away, but as much as it pained you, you forced yourself to stay away until after he was convicted. Neal was considered an extreme flight risk; any interactions he had were extremely closely monitored. No matter how loyal you were, you were still afraid of being in trouble for failing to give up his name and whereabouts. And while that made you feel quite selfish, there was also the detail that he’d been “caught” by voluntarily walking into a trap to protect his girlfriend from taking the fall for him. It comforted you that he was still the same softhearted man you’d always known and loved – but, since he’d always been fiercely protective, you weren’t sure if he’d welcome you jeopardizing your good standing to see him.

Well, too bad. You winced. Okay, maybe a little more sympathy for the guy in prison.

You signed in a civilian, not an agent, in the hopes that the bureau was less likely to be notified. You weren’t sure what you’d say, but you couldn’t just leave Neal to rot alone in here. The place looked like the place of nightmares, and you were free to just turn around and walk out the door. Your heart ached. God, Neal…

They searched you quite invasively, but that bit of your dignity was a small price to pay. Once satisfied you weren’t using your body to smuggle a nail file or the like, the guards had you wait while they fetched Neal for visitation and put him in a small monitored cell, then allowed you to be led back the same way. The moment you realized he had to have visitors in a cell with him, it felt like your heart skipped a beat. You knew his containment orders were serious, but to not even be permitted to use the visitation room? This was the kind of restriction that was usually placed on quite dangerous felons.

There was already one guard standing inside with Neal, close to the door but warily watching. You could tell from his profile, in the ugly orange jumpsuit, that his wrists and ankles were manacled together and locked to the metal table. As the guard who’d led you back let you enter, the guard already inside gruffly barked the rules: fifteen minutes, follow the tape on the floor to your seat (rather than take a shortcut which passed closer to Neal), and absolutely no touching.

You ventured in as Neal turned around as well as he was able to see you. The surprise in his eyes was quickly taken over by delight and he started to stand, only to get yanked down by the links around his wrists. That sight alone nearly killed your excitement to see him, but he remained undeterred. “Marbles!” he cheerfully chirped your old name.

You forced a little laugh, loosely sticking to the tape and hurrying to your side of the table, swinging your legs in comfortably to sit across from him. “You are such an ass, Neal,” you complained with a small smile.

There was almost a little look of shock when his chosen name came out of your mouth so casually, but before you could respond to it, it had melted into a soft smile that lit up his eyes. He looked at you like you’d put the sun in the sky for a long minute. “I’ve missed you,” he said quietly.

“I’ve missed you, too,” you risked answering, not daring to look to the guard. Hopefully he wouldn’t remember this bit. “When you… well, I thought for years that was it.”

“It wasn’t meant to be,” Neal admitted. It was easy to say that now that it was in the past and you’d gotten back in touch, but you couldn’t help but trust him. Neal had never told you an outright lie before, not for any reason. “Things just… is it too cliché to say I needed to find myself?”

You hesitated, but shook your head. “No,” you said haltingly, “But there were better ways to do it than becoming a milk box picture.” You’d imagined screaming in his face for it, giving him a real what-for over the way he left you to pick up the pieces he left behind. But now that you were here, in a prison where he’d be spending the next half decade of his life – well, it was hard to hold onto any anger. Neal was paying for his mistakes. You didn’t need to pile on with trauma you’d already processed. “Did you?” You gently prompted, sensing that if you didn’t, he was going to wait for you to say what you’d thought about.

His smile tightened into something wistful. Your heart sank a little for him. “I think I got close at times,” he allowed. You didn’t quite buy it, but thought if he needed to believe it, it wouldn’t hurt to let him tell himself that all of this was worth it. Like he’d always done when he was unhappy, he turned the subject around back to yourself. “I’m so proud of you, Y/N. I knew you’d make something good for yourself.”

We could’ve done it together. You thought back to his eighteenth birthday. You’d been so close to telling him you were going to take that next step with him. Maybe if he’d known it wasn’t just his journey… well, it didn’t matter now. It was ten years in the past.

“Stop talking like we’re in retirement,” you accused lightly. If it weren’t for the guard who felt very strongly about touching, you’d have nudged his foot under the table. “We’ve got ages to make more out of ourselves yet still.”

“You do,” Neal disagreed graciously.

“No, we do,” you argued, saying it so firmly that he wasn’t allowed to disagree again. Then you softened your tone, because you knew he already knew how bad this was going to be. “Four years… it’s gonna be hard. But one day it’ll be done and you’ll have a whole life in front of you to do something new.” It was the twenty-first century. When he got through his sentence, he’d still have more than half his life expectancy ahead. “And we’re gonna make it good. Got it?”

Neal’s expression had hardened a bit, for a moment showing his anger. When he was Danny, he’d been good at concealing anger, but when it did come out, it was volatile. Ellen wanted to put him in therapy to better manage it, but his mother had never gone through with it, so Neal had been left learning to self-soothe and manipulate his own emotions until he could explode in private. It wasn’t pretty. And, unfortunately, based on that familiar expression he’d made, that habit hadn’t changed. But when you were done, he seemed to assess what you were saying and judge it on the merits of your own belief in it, because he studied your face as he slowly nodded, and the anger slipped away, either unwinding from his joints or being masked by something else. You hoped for the former, but truthfully, it had been ten years. You’d once known him better than anyone. While you still suspected that that was largely true, you couldn’t be sure this hadn’t changed.

“We will,” he echoed after you. “You’ll be here?”

You nodded with certainty. If nothing he’d done so far had gotten you fed up with him, there was probably nothing he could manage from inside a prison to change that. “I will.”

You put a hand down on the table. The guard locked his eyes on it and you barely refrained from rolling your eyes. Symbolically, you were offering Neal a hand to hold. Judging by how exasperatedly he glanced at the guard, he understood as he made an exaggeratedly slow motion, mirroring your hand but not reaching across to you.

“It’s gonna be a long four years,” Neal grumbled under his breath, shooting an irritable glare in the guard’s direction.

~~~

~~~

A/N: Wow! This ended up twice as long as I planned because I got really into it and carried away a bit. I might even be open to a continuation... Anyway, if you liked it and want to get announcements about stories and chat about what's coming up, leave a comment asking to join the Discord and I'll send you a link!

#white collar lawmen and conmen#white collar#white collar x reader#neal caffrey#neal caffrey x reader#platonic#x reader#friends#reader insert#oneshot#fic#requested#anonymous#james bonds#neal bennett#danny brooks#pre-series#marbles#fbi reader

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good evening, White Collar fandom.

521 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elizabeth: Peter and I are having a baby.

Neal: That's gre-

Elizabeth, slamming adoption papers on the table: It's you, sign here.

676 notes

·

View notes

Text

People included in Leverage, Inc. teams (please add to this):

People the team met during the original Leverage run, aka clients, the occasional mark (Hurley, maybe Widmark Fowler technically), and some "side characters" (thinking in particular of that kid Eliot saves in the hospital in The Order 23 Job, Randy).

Friends and friends of friends, including Mr. Quinn and (sometimes) Tara. (Not Chaos, ever. All Leverage, Inc. teams are briefed on how he killed Lucille. Twice? They know it's a van, but it was clearly important. If they run into him, it Comes Up. He will be held accountable.)

Hardison's siblings/cousins/extended network of people associated with them via other placements. These are a wide variety of people who have gone on to places across the country/world and jobs in different fields; if you need a place to crash, they are everywhere and very accepting, and if there's something Hardison (or Eliot) doesn't know, Hardison (Nana) has someone in this network who does.

Random people they know by reputation and check out through massive invasion of privacy. (I have a headcanon that Neal Caffrey from White Collar got recruited after the end of that show.)

#Leverage#Leverage Inc.#And a bonus mention for#White Collar#and#Neal Caffrey#How many times did Chaos kill Lucille? Because I might have gotten it mixed up because of the number of times I've been impacted (3).

491 notes

·

View notes

Photo

White Collar S04E01 & S06E06

↳ By Request

#white collar#whumpedit#peter burke#emotional whump#loss#grief#men crying#tears#sobbing#wc 4x01#ep: wanted#wc 6x06#ep: au revoir#requests#i hope you like it dear#yellow is the bane of my existence

407 notes

·

View notes