#relating to others

Text

“Where are you from?” “Earth, I guess.”

Though this article isn’t exactly an analysis of a theory, it is meant to be an examination of an idea, so I suppose it still falls under the purview of this website. As I may have alluded to in a few of my other posts, I did not grow up in my parents’ home country. Born and raised overseas for the first sixteen years of my life, I identify more strongly with the East Asian cultures wherein I grew up than the Western American culture my parents grew up in, and which I returned to visit every five years. That self-identification isn’t necessarily correct — I have more American attributes to me than I initially thought, of course — but there is still a very real component of disconnect.

The more technical term for someone like me is a third-culture kid, or a TCK. For a TCK, where their parents were from, where their last name probably came from, and what nationality they look like are all components of what we call their passport country. My passport country is America. Where the TCK and their family lives is called their host country. My family moved around a lot, but my three host countries were in East Asia. The reason we’re called third-culture kids is that we were raised with elements of our parents’ culture in a locale with a different culture, so we naturally blend them both, making it a sort of third culture.

When I talk to people in America and they find out I’m a TCK, they’ll ask me questions like, “So are you East Asian?” or “Are you a real American?” or “Do you like America or East Asia better?” I’m certain I’m not the only TCK who’s been asked questions like this. The truth is that most TCKs feel more like, well, a TCK than someone from either country — and most of us will feel more at home with other TCKs than we will with people from either our passport or host countries, even if each other’s countries aren’t the same. For example, a Singapore-based, Nigeria-residing TCK could likely feel more at home with a Russia-based, Italy-residing TCK than either of them will with someone from their respective host or passport countries.

This makes a lot of sense when you think about it — people identify home with community, and people identify community with people like them. The most similar thing to a TCK is another TCK, so it only makes sense that they’ll feel the most community — and the greatest sense of home — there. Because of this, TCKs can often struggle to create proper connections with non-TCKs. Many TCKs find it a challenge to communicate how important their cultural background is to the people closest to them — I certainly have — and it can be hard to help non-TCKs really understand them. My hope is also that through this article, non-TCKs who are close to TCKs can gain some insights into how they operate, and perhaps some things to know when interacting with them. So I’ll break down a few things about TCKs here — why we can struggle to make friends, what we carry, and what we probably wish you knew.

I’m not even going to get close to covering everything about TCKs in this article, nor would I want to. There is a lot of weight that comes with it, and some parts of it are just better left unsaid. Feel free to comment any questions you have below, and I’ll try to answer them as thoroughly and honestly as possible. Finally, because my take on this topic is completely experiential, I’ll do it a greater service by being more narrative than analytical.

Why we can struggle to make friends

I was on a phone call with some of my TCK friends and we happened to be discussing this exact question. There are a lot of reasons, and I want to break them down and explain how the TCK life can bring them to these conclusions.

“I’m tired of starting over.” I can’t even count how many times I’ve heard this. I read an excellent (and very accurate) article called TCKS: The Most Heartless Things that stated that TCKs found solace in pretending they were all fine together. And that’s not wrong. The article says it better than I can, so I’ll just quote it:

TCKs can be some of the most masochistic people ever—always anticipating leaving their current location then detesting for no reason wherever they go next… we all, to some extent, act like we’re used to it. And strangely enough, we find the most comfort in knowing that we’re all letting each other pretend like we’re okay. As one of my best TCK friends said to me once,

“We live for the pain-joy of those awful last two weeks, three weeks, whatever.” The time when we finally realize how incredibly happy we are here with these people and we can finally let it all go for these last few weeks before we all scatter again, after all these years of wishing we weren’t here, wishing we were grown up, wishing we were with someone else. We live for this feeling of being insanely full of happiness and full of deepest sorrow at the same time.

What this author is saying, effectively, is that TCKs start over a lot — and every goodbye is something like a death. Part of you dies, that place is dead to you, many of the relationships are dead to you. A lot of TCKs have to say goodbye so many times that they harden to making new relationships as a way of protecting themselves from future pain. I can’t think of any TCK I know that hasn’t felt this for at least some considerable amount of time. This is why the author also says we live for the “pain-joy of those awful last two weeks.” The author is referring to the final weeks before a move, because then you can be happy, realizing that your grief about leaving means you actually liked the place somewhat, that maybe you didn’t harden as much as you thought you did. I’ll come back to this idea of pretending to be okay later, because it will be important.

“They’ll never understand.” This one is also very common. The TCK life is very hard to explain to others who have never lived cross-culturally, because it is hard to communicate the weightiness of constant transition. TCKs are always hovering on the brink of instability, knowing that they don’t belong to either place but not sure where they do belong. And because this is such a deep and ingrained part of our life experiences, it can feel like someone who doesn’t understand that probably won’t understand us.

“Monocultural people are just so ignorant.” Now, it’s important to remember that this is a TCK perception of a group, and there will always be exceptions to the rule. But when a TCK says someone is ignorant, they usually mean that the person hasn’t learned how to notice and respond properly to interpersonal differences. They may mean the person is inattentive to other people or that they lack a broader understanding of the world. TCKs have grown up constantly encountering new information, and they learn a lot of hard things at a young age. To them, ignorance is a cross between a lack of knowledge and a lack of maturity. Because their background tends to spur them ahead of their monocultural peers in terms of maturity, a lot of TCKs are disinclined to make monocultural friends because of what they feel is a disparity there.

This one is particularly pertinent to America, but I’ve heard a lot of TCKs say they’re resistant to making friendships with Americans because they find them very shallow. This idea is complicated and, ironically, culturally derived, but I think I ought to explain what a TCK means when he or she says this. If you have grown up your entire life face-to-face with your weaknesses and confusion, in a community living the same way, trying to find a balance between yourself and an outside culture, then you come to grips with your deficits very quickly. Because everyone in that community is dealing with the same (deep) issues of the self, identity, community, truth, belonging, etc. on the same (deep) level, we kind of drop the standard barriers to deep, personal conversations. We’re all in the same boat, so we may as well talk about it. For this reason, some TCKs will say that if conversation depth can be measured on a scale of 1-5, with 5 being the deepest, even get-to-know-you TCK conversation will start around a 3. Standard American small talk, on the other hand, will start around a 1. If the TCK has formed their immediate community with individuals who all start around a 3, it is a really severe culture shock to be forced to talk on level 1 — and many TCKs new to America have never had a 1-level conversation before, so they simply don’t know what to do with it. A TCK can sound condescending when they call Americans shallow, but what they’re trying to communicate is that they don’t know how to engage in conversation with someone who hasn’t had to think long and hard about who they are and where they belong like the TCK did. The TCK lifestyle forces a lot of self-reflection and self-awareness, so TCKs can struggle to converse with others who have had less practice being thoughtful and self-aware.

So to most TCKs, there is something very attractive about other TCKs — they both feel like displaced foreigners, and so at the core level, they share a sense of unbelonging. That sort of feeling can bond TCKs very quickly, because they share the same foundational framework for viewing reality. When TCKs are put in monocultural settings — especially the ones in their passport country — they can feel discouraged, confused, dismissed, and misunderstood. The experiences overseas that brought them pain and joy and solid community and confusion are suddenly turned into conversational talking points or showpieces. The non-TCK can’t relate and often either chooses not to care or asks questions in a way that can feel devoid of real understanding. The TCK is just looking to be understood, like everyone is when they’re looking for a friend. TCKs just have tighter exclusion criteria, because they’re harder to understand. This leads into the final reason TCKs often offer, which I think is especially practical for non-TCKs.

I call this the axis of attention. When I think back to all of my experiences with non-TCKs, I can categorize almost all of them on an axis ranging from “You are not your culture; I’m going to treat you like you’re normal,” to “You are your culture, and that is what interests me about you.” It seems like most non-TCKs, when they meet a TCK, feel like they have to fall in the right spot on this axis in order to treat a TCK properly. So they totally ignore their cultural experiences, or they ask loads of well-intended really invasive and rude-sounding questions, or they try to vacillate perfectly along that line so that they do it “right”. But, coming from the source, that is not what we want you to do. The most helpful attitude isn’t anywhere on that axis, because that axis tells the TCK that the relationship is defined by how the non-TCK responds to what they find hard to relate to. Or, more formulaically, my plan for operating in our friendship = how I act about the confusing parts of you.

To give you an easier image of this, imagine that you meet someone with a really life-altering disability, like hemiplegia (lower-body paralysis). You want to develop a friendship with them, because they have an interesting personality and a lot of charisma, or something else that you like. If you focus all of your effort on making sure your new friend never feels like you notice or pay attention to their disability, you’re going to make them feel neglected, dismissed, and uncared for, because that’s an important factor that affects their life. And at some point, you’ll accidentally take them somewhere that only has stairs and no wheelchair ramp, because you won’t have any practice thinking about how the disability affects their life. On the other hand, if you focus all of your effort on making sure they feel like you really value how the disability impacts their life, you’ll likely make them feel like that’s the only thing you find interesting about them. Your problem is that both of your strategies revolve around how you see them, and not what you see together. I would rather a non-TCK spend the first, like, four to six hours of our interactions at minimum just trying to find points of interest and connection. If my TCK background comes up, great — try to find points of connection there. But don’t think too much about how you see it. Think more about what we have in common, whether or not it incorporates my cultural background. This is how all TCKs make friendships and how monocultural people make friendships as well. Crossing the bridge can be scary and can make you wonder what strategy you’re supposed to use. As you get to know the TCK and develop a deeper relationship with them, paying more attention to their cultural background is important. But especially early on, the more you think about how you’re thinking about their cultural background, the less effective you’re likely to be.

What we carry

It’s important to say, before going into this, that there are very few TCKs who carry light weights. A lot of us have seen really hard, painful things, and not all of those things have been properly processed. If you’re a non-TCK, it’s especially important that you be very careful not to prod about them before the TCK is ready to share them. This is primarily because the TCK more than likely is expecting you, as a monocultural person, to fall on the axis of attention, to be culturally ignorant, and to misunderstand their experiences. Maybe they’re wrong about you, but they’ve been right about too many people before (or tried to trust them and found they were wrong) to open up right away. TCKs live with a very strong feeling of difference and displacement, and if they think you’ll take something badly that really matters to them, they won’t risk having it hurt again. So what you should not do is approach a TCK you’re getting to know with encouragements to “just talk about it”. A lot of TCKs can feel like this is you trying to win status by winning their self-disclosure, which, even if you didn’t mean it that way, will just close them off more. Instead, you should ask genuine, simple, specific questions with clear reasons for why you want the answer. It’s not that we don’t want you to take a genuine interest in our background — we do, desperately. We just don’t want it to feel fake, and we’re really good at reading that into what people say. We’ll come back to asking TCKs questions in the next section.

So what kinds of things do TCKs carry? Some of them have been woven throughout this article, but here they are in summarized form:

Unresolved grief: we say goodbye a lot, we say it quickly, and we go to the next place. We don’t have a lot of time to process things, and it’s often easier to shove out the sadness in the go-go-go rush of moving to a new place again. If all the moving also means your friend group constantly changes, you also don’t have a stable support network to process the grief within, which means you’ll often isolate yourself to avoid being re-hurt. Like I said above, every move is a series of deaths, so many TCKs have seen a lot of deaths they might not have wanted to see.

Communal disconnect: I elaborated on this a lot more in the other section, but TCKs can feel very acutely that they are alone in a crowd of monocultural acquaintances. They don’t always feel that they belong in their passport country or their host country, and because this is so hard to communicate, they often decline to share. This leaves them alone once again, waiting to find the next TCK and the next pocket of understanding.

Unbelonging: this one is rather obvious — a lot of TCKs move around a lot, but even the ones that don’t can still feel like they don’t belong. After all, the locals see them as a foreigner, but when they return to their passport country, the people who feel like foreigners to them assume they are a local. It gets wearisome explaining where you fit to both sides, and after a while, you’re not sure which side you belong on, or if you belong on a side at all.

Spastic friendships: all of the goodbyes mean that you don’t keep most people around for very long. And sure, as a TCK, your small talk starts three times deeper than the standard, but your friendship ends three times faster than the standard, too. I and my friends sometimes speculate that we start deep so we can actually get to something valuable before one of us just up and leaves again. It’s hard with the TCK lifestyle to find a long-lasting friendship with someone who’s known you a while, who can keep you accountable to things, and who understands you deeply. You expose your raw brokenness to strangers for three, six, nine months, and then one of you is gone. You have a great friendship for that time, but then it’s over — and sure, you pick back up when you talk again, but the friendships are so transient that you have very few people who know you very closely for a substantial amount of time. Just as an example, between the ages of nine and seventeen, I did not have a really solid friendship that lasted longer than six months. It was only shortly after I turned seventeen and stayed in one place that I secured a lasting, deep friendship with someone. It’s lasted over a year, and that hasn’t happened since I was eight.

High responsibility but low sense of control: this one is especially interesting to me. Because we move around a lot and/or have to adapt a lot, we realize very quickly that our success in our environment is contingent upon our ability to recognize social cues and adapt properly to them. For this reason, TCKs tend to take initiative at high levels, be proactive in their environment, look for opportunities, and exert agency in a productive manner. Consequently, most TCKs tend to see themselves as fairly responsible for their success. At the same time, the TCK realizes they had no choice over their location, or how much they moved, or what cultures influenced them. The TCK rarely gets a choice when their family needs to move again, or when they need to start again at a new school, or when their schedule gets upended because the family or immediate community needs something. They don’t get a say in their friends or what questions people from their passport countries ask them. So there are a lot of things TCKs can’t control, but they still often feel acutely responsible for their success. In some ways, this can be healthy and helpful, but in other ways, not so much — it can easily lead to negative feelings that life has it in for them, or that their agency isn’t worth much since they can’t choose most things themselves anyway.

Despair regarding transience: I’ve certainly struggled with this one a lot. I was only eight years old when I decided that everything that I looked forward to about a new place, new friends, or new things would go away too quickly to be worth all of the wait. Because my circumstances changed so much, and the things I enjoyed with it, I felt for most of my life like there was little stability to be found in a place, a feeling (especially happiness), or other people. After all, if things change all the time, why rely on them? Once they get pulled out from beneath you, you’ll fall down — best to not try to enjoy things that won’t even stay around. That mindset isn’t necessarily robust, but it’s very easy to feel that way when you move often, change friends constantly, or feel endlessly displaced.

Hatred towards God: this is especially relevant for kids whose parents live overseas because of religious affiliations. At least a third of my TCK friends to some degree blame God for the challenges the TCK life has brought them, because they feel that he has forced their family to live overseas and instigated all of the hard things that happened as a result. Because of this, many religion-purposed TCKs can struggle with doubting whether God actually cares or loves them or whether he is there at all.

These are very complex feelings and ideas, and they aren’t things TCKs share with just anyone. If a TCK shares this with you, it’s probably because they think you’ll make an effort to genuinely understand them. Depending on the TCK, they can have a lot of baggage from things that happened to them — witnessing deaths, negative interactions with government bodies, severe loneliness, racial discrimination (depending on their host country), reentry distress, financing challenges, living with threats to their lives, and so on — that you more than likely have no idea how to respond to.

If you’re a non-TCK, the seemingly endless stories of adventure, pain, and heartbreak can seem overwhelming and different, and you may not be sure how to handle it. Remember that it’s okay to not know what to do. Here are a few tips, though, if a TCK opens up to you about the hardest parts of their experiences:

Don’t assume that your experiences compare. If you moved from Alabama to Delaware, I’m sure you experienced some cultural changes, and that’s definitely hard, but that is not the same thing as what the TCK experienced. For points of friendship connection, finding ways you can relate to each other is a good thing. When the TCK is sharing their hurt with you, trying to make your story relate is not a good thing. It can make the TCK feel like you are misunderstanding their experiences or devaluing what it was actually like, and they’re very likely to shut down. Unless you’re a TCK, don’t act like you can relate to the TCK’s background. Immigrant kids can relate on some level, but it isn’t the same as a TCK, so while there are points of connection, don’t make yourself sound like a TCK if you aren’t one.

Don’t assume they’re bragging. We have a lot of “crazy” stories, but remember, these stories are our normal. Maybe we rode elephants five times, maybe we were chased by village attack dogs, maybe we had people take our photo everywhere we went, maybe we speak six languages. But we grew up doing those things, so it can be hurtful for other people to constantly assume that we’re flexing any time we talk about our lives, and it furthers the feeling of difference and displacement. We’re telling you stories about our lives because we’re trying to help you understand us, and because we’re trying to connect with you. We want to feel understood, and if we’ve decided that you’re worth a shot, we’ll tell you our stories because we think you’ll be able to understand us if we explain. Just because it would be something you’d brag about if you did it on vacation doesn’t mean it’s something we’re bragging about.

Let them talk. Just listen. We may bring in fifteen subpoints (I certainly do) in our attempt to explain. When we do that, we’re just trying to give you all the context, because we don’t know what you know about cultures and life overseas. We have a lot of untold stories, and a lot will come out on the person who listens. It won’t be orderly often, because we usually cram it inside ourselves. Just be patient with us.

If you don’t understand something, ask. Also, if you’re really curious about something, ask. We like talking about our countries and our experiences, and we understand our lives well — so explaining it to someone who really cares is fun for us. If we use a term you don’t recognize, just ask what it means when we finish the sentence (bonus points: remembering the term and then using it in an appropriate context in a question or statement later is extremely meaningful. This is because the term we gave you is probably an “insider term” that other TCKs from our community use, so using it is a clear attempt on your part to understand us well). And if you’re genuinely curious, just ask us. If you really want to know what Japanese ice cream tastes like, ask. But one way you can make these questions more inviting to the TCK is by explaining why you want to know. Asking a bunch of seemingly pointless questions can make the TCK feel like a show exhibit. Instead, explain why you’re curious about the thing. For example: “I’ve heard Asians don’t like sweets as much as Americans and I found that really interesting. Did you ever notice if the Japanese ice cream flavors were less sweet because of that?” or, on a deeper level (especially if you’re trying to take an interest in their background), “I’ve heard that Japanese people can be self-isolating. Is that true, and if it is, how did that affect you during your time there?” These kinds of questions are helpful because they give us something specific to answer as well as a reason you’re taking a particular interest. You sound interested in our thoughts — not in what interesting facts we can spit out in twenty seconds.

As a final note, if you are a friend to a TCK, there are probably a few rogue cognitive distortions that they’re harboring — and they might not recognize them because they’ve not talked to people about their TCK experiences. If — and that is a very important if — you are close enough to a TCK that they’re willing to share their experiences with you, you may want to consider that you are in a position to (gently!) challenge some of their distorted thought patterns. You can help them by encouraging them to examine their thoughts about transience, lasting friendships, God, or community. These distortions are another thing they carry, and if you’re very close to them, you can help them let go. Feel free to ask more about this in the comments if you’re interested in how you can do this.

What we probably wish you knew

I’ve covered a lot in this article, so we’ve touched on many of the things TCKs wish non-TCKs would know. But there is one thing I want to comment on about TCKs and inter-TCK interactions and community that I think a lot of non-TCKs misunderstand.

This is the idea I mentioned earlier that we all take some comfort in pretending that we are fine. For the TCKs that I’ve interacted with, there is something relieving about knowing we have all experienced enough pain that no one needs to be surprised or turn on therapist mode. We take our experiences as they are, swap crazy stories without needing to filter them or explain terms, and disregard cultural norms wherever we see fit. The difficulty is a given, and that’s both a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, we like that no one feels estranged for having a heartbreaking backstory. On the other hand, it’s kind of heartbreaking that that’s the way it is.

We act like we love the life, the constant change, the cultural exposure, and the hard things that force us to grow — and in a lot of ways, we do. But remember that that isn’t all there is. It is a sharp “pain-joy”, the kind of thing that makes us cry, but the thing we’re glad to cry about. The same author I cited earlier adds,

When it’s a party of TCKs, we eat inordinately huge slices of hummingbird cakes late at night, viciously spearing with forks the decadent plumage whose flavor we cannot label—banana? pineapple? blackberry? coconut? We blow clouds of soap bubbles in each other’s faces… and tell stories about people we love who are in heaven now, but only the funny stories, the stories that make us laugh…

The laughter—that’s the most important part. The cackles and snorts and delighted shrieks that swell and rise out of our throats and fill the apartment and overflow down the hallway. We bang our hands emphatically on the table, clutch at the walls as our knees buckle and our sides are throbbing with all the joy and we eventually give up and collapse on the floor and we can’t breathe.

The can’t breathe is when it gets dangerous. Because in that moment of sheer white oxygen-deprived hilarity, everything goes quiet in your mind and all of a sudden it is incredibly clear what will happen too soon. It happens in a split second: the heaving in your chest is no longer from breathless laughter but a flood of tears rushing up your windpipe, a tingling gush sweeping through your sinuses, and you tilt your head back as fast as you can to balance the emotions on your eyeballs. But no matter! Mr. TCK-from-Japan-but-is-German-with-an-American-accent to the rescue with more bubbles in my face and open mouth, and I sputter and blink away tears and roar in indignation, and the tribal dance starts up again. Moment of danger safely behind, only slightly bruised.

I love this illustration, because it captures very precisely what a lot of my experiences with my TCK friends are like. We don’t always know what we’re eating. We know we’re emotional wrecks, and we laugh about it until we cry, and then we laugh some more. Our lives have asked a lot from us.

So here is what we wish you knew: when we cry, we don’t always wish we weren’t; when we laugh, we’re not always glad we are. It is not a light weight that we carry, but the weight draws us deeper into reality, and that is valuable. We can be painfully joyed by our experiences simultaneously. There’s a lot of emotional weight that comes with the TCK life, and it sometimes feels like we have to laugh it all away. That is not always a bad thing — our stories are complicated, and so are our feelings. It means so much that you just experience the feelings with us — even if they change.

Again, if you have any questions about the TCK life or want resources to understand them more, ask in the comments, and I’ll try to answer as well as I can. In a few weeks, I and one of my best TCK friends are going to co-author a follow-up article talking more about the benefits of the TCK life and other miscellaneous things, so keep an eye out for that if you enjoyed this one.

#tck#third culture kid#expat#expatlife#east asia#repatriation#social issues#relating to others#friendships

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

TODAY New Moon in Libra September 2022: New Ways of Relating - Moon Omens

The New moon energy will still be useful tomorrow even as other planets shift... Have fun with it. It's all good stuff!

Blessed be.

#♏

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

shoutout to everyone who wants to infodump but cant string together coherent thoughts to form sentences and instead just look at you like this

#and by 'everyone' i mean me. im just hoping other people relate lmao#someone asks me about a thing i like and im just like h..................#been thinking about The Character for a solid 6 months+ and let me tell you. expldoeing soon#this is about ffxv btw . how am i supposed to say how much it lives in my brain . i cant think#text#1k#5k#10k#15k#20k#great googly moogly#30k#40k#50k#60k#boooy what da heeel#70k#80k#90k#will this be my first ever post to hit 100k... it remains to be seen#good lord. we did it#100k

119K notes

·

View notes

Text

It's honestly crazy that discussion around testosterone HRT skews so much towards the beginning stages of it (to the point that you have dozens of guys thinking their transition is "failed" if they don't pass by like a year in lol) and what the initial changes of the first couple of months to years look like, like the classic laundry list of those early basic changes like bottom growth, voice drop, etc, when IMO literally none of that compares remotely to the depth and intensity of the long term total masculinization you start to experience like 3-5+ years in.

#also has made it increasingly difficult to relate to those early into their transition honestly#like not in a bitter way it’s just like hard to express how diff the experience is#of being like a year on T vs 5 😭#ETA I muted this post ages ago now but fwiw seeing transphobes pop up in the notes on occasion just to say cruel reactionary shit#you are clowns I cannot imagine seeing a post that is ONLY about discussing with folks about the reality of a medication#and choosing to make that your moment to get a schoolyard bully jab in about how you find it gross or something.#you are less well adjusted than most children. may the universe be kinder to you than you are to others.

50K notes

·

View notes

Text

“these characters should be mentally healthy before they get together 😌” ummm no I actually think we should smash their mental illnesses together like clumps of play-doh and see what colors it makes

#they should live under each other’s skin in a way that’s weird to everyone else. actually.#also on a more serious note since this is getting notes mental illness does not preclude people from deserving love#or the ability to give and receive it#it also does not make you inherently toxic#sometimes people are just toxic anyways of course#and a lot of people enjoy a toxic ship and are relating that to this and that’s cool!#but like#if you believe that’s the only option you’re wrong buddy#people can be worse together but they can also be better#acting like a character or a person has to ‘fix’ their trauma or what have you to be worthy is. a fucking weird mindset.#but anyways!

36K notes

·

View notes

Text

#polls#remaking bc i forgot to change to 1week.#but yeah us latinos smelling so damn good while showering everyday while some other places.....like.....ew#just some perfume.over their sweaty ass...or not even that...cant relate.#brasil tag#t.txt

26K notes

·

View notes

Text

was talking with a friend about how some of dunmeshi fаndom misunderstands kabru's initial feelings towards laios.

to sum up kabru's situation via a self-contained modernized metaphor:

kabru is like a guy who lost his entire family in a highly traumatic car accident. years later he joins a discord server and takes note of laios, another server member who seems interesting, so they start chatting. then laios reveals his special interest and favorite movie of all time is David Cronenberg's Crash (1996), and invites kabru to go watch a demolition derby with him

#dungeon meshi#delicious in dungeon#kabru#kabru already added laios as a discord friend. everyone else in the server can see laios excitedly asking kabru to go with him#what would You even Do in this situation. how would YOU feel?#basically: kabru isnt a laios-hater! hes just in shock bc Thats His Trauma. the key part is kabru still says yes#bc he wants to get to know laios. to understand why laios would be so fascinated by something horrific to him#and ALSO bc even while in shock kabru can still tell laios has unique expertise + knowledge that Could be used for Good#even if kabru doesnt fully trust laios yet (bc kabru just started talking to the guy 2 hours ago. they barely know each other)#kabru also understands that getting to know ppl (esp laios) means having to get to know their passions. even if it triggers his trauma here#but thats too much to fit in this metaphor/analogy. this is NOT an AU! its not supposed to cover everything abt kabru or laios' character!#its a self-contained metaphor written Specifically to be more easily relatable+thus easy to understand for general ppl online#(ie. assumed discord users. hence why i said (a non-specific) 'discord server' and not something specific like 'car repair subreddit')#its for ppl who mightve not fully grasped kabru's character+intentions and think hes being mean/'chaotic'/murderous.#to place ppl in kabru's shoes in an emotionally similar situation thats more possible/grounded in irl experiences and contexts.#and also for the movie punchline#mynn.txt#dm text#crossposting my tweets onto here since my friends suggested so

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

Of the 19 hijackers who carried out the Sept 11 attacks:

15 were from Saudi Arabia (a powerful/oil-rich country the U.S. works hard to maintain diplomatic relations with)

2 were from the United Arab Emirates (also a powerful/oil-rich country the U.S. works hard to maintain diplomatic relations with)

1 was from Egypt, 1 from Lebanon.

None of the hijackers were from Iraq.

None of the Sept 11 hijackers were Iraqi.

None of the 9/11 hijackers were from Iraq.

#9/11#serious post#not a shitpost#this should be one of the first things kids learn when they learn about the 9/11 attacks#politics#this is just...it's such an essential and brazen fact and i rarely see basic outrage over it#i want outrage. i want fury. i want disgust over the way fundamental facts are disguised and discarded and downplayed#because there are things we should KNOW. basic fact we should ALL KNOW. and they are tucked away in the footnotes.#and no this is NOT to put the blame on other middle eastern countries#we know this was carried out by a specific terrorist organization not a national government#but King George the Second decided (and was encouraged by his cabinet!) to invade a nation!#a nation that was not at all related or responsible!!!#a dictatorship to be sure--but a dictatorship that King George the First had been happy to support#so what changed? why did we go in guns blazing to DEMOLISH a country *we had NO PLANS OF REPAIRING*???#well. because they wanted a villain didn't they. a nice clean war. clarity of purpose. us the heroes against them the villains#and when you're in that mindframe--truth is irrelevant. you can pick your villain (your victim) by rolling a roulette wheel#truth is irrelevant#worse: to the people in charge#truth is a HINDRANCE#'Alternative facts' existed long before it became a catchphrase#facts don't matter. truth doesn't matter. the impulses of a handful of volatile & rich & power-high people--that's History. congratulations

33K notes

·

View notes

Text

i have such a love for characters who descend into madness or villainy out of deep, deep empathy. characters who fundamentally cannot cope with the cruel realities they find themselves in and blow up about it in spectacular fashion. fallen angel type characters with tears of outrage in their eyes. characters who break before they bend, and break so badly they splatter blood all over their noble ideals. every variation on it gets me so good

#getou suguru#kaneki ken#abyss twin#i know there are others who im not thinking of rn#feel free to reblog with more examples#aphelion.txt#tropes#WAIT I REMEMBERED MORE#jaina proudmoore#dimitri alexandre blaiddyd#phosphophyllite#i just spent like half an hour trying to find this on tv tropes but it must be. Too specific of a thing i have in mind bc#I just kept finding similar and related but too broad categories#despair event horizon. fallen hero. well intentioned extremist. etc etc etc#like specifically i'm talking about when the character's EMPATHY is the CRUX of the problem. sosooo crunchyjuicytasty#edit:#also just know that i am reading every tag on this post#and enthusiastically scribbling down the names i dont recognizr#so i can check out their series later#edit 2 wow this post blew up 🫡 godspeed fellow villain likers#the amount of people tagging this as 'me lmao' is concerning to me#wwx#how did i fucking forget this was also yllz era wwx

30K notes

·

View notes

Text

archivist be upon ye

#relistening to tma again#i think the last time i’ve drawn anything related to it was like may 2020#god it’s been a while#have been listening to the magnus protocol and my god it’s so good#but heres good old jonathan as a treat#the interest has been in deep slumber for the past 4/5 years only periodically coming back to life#i’m very normal about this podcast actually#on other note i also started a taz balance relisten#what’s up with me and revisiting my middle school fixations lately#anyways#if you’re still reading these tags i’m impressed i could never with my abysmal attention span#tma#the magnus archives#the magnus pod#jonathan sims#the archivist#tma jon#fanart#my art#digital art#illustration#doodle

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Y’all, the Archive admins are made up of VOLUNTEERS. And they have been working for 12-13 HOURS STRAIGHT.

I better not hear any complaints when donation period comes around. OR ELSE.

cosplay by @woahchriswoah on Twitter

EDIT: How do we show appreciation to the volunteers? For me reading these deep dives on OTW issues u guys apparently it's been said multiple times that one of their objective statements is to have paid staff for ao3 and there's a surplus of donations they haven't used up or the other community solutions that needs to address. For those more financially literate feel free to analyze, snipe me or add to the discussion etc. linked here by deepa. They’re cool and these yearly analysis they did aint no joke.

But Seriously what can we do for these volunteers? The probable burn out from this entire fiasco would be no joke. @ao3org

#can we give them hot cocoa or smth#sorry if the org is so pressed rn#but gotta psa some of these issues while the iron is hot#and post is gaining traction#DDoS is over for AO3 but now it’s targeting other NGOs related to OTW org it’s despicable#EDIT 2: AO3 is Back :3#EDIT: WE ARE PAST 24 HRS BUCKLE UP FOR A LONG RIDE#no devil works harder than ao3 volunteers#archive of our own#ao3#ao3 update#btw yall know I’m not forcing anyone to donate right?#i mostly made this to the regular karens who bash the archive anytime they ask for donation#ddos attack#hackers#fanfic#fanfiction#fandom#spn#supernatural#tags to better circulate this news#destiel#lol#hobie brown#spider punk#spiderverse#no hate

25K notes

·

View notes

Text

this is going to sound simplistic + i promise you it's not: stop following people whose entire schtick is being cruel or fighting with others online. even if the ppl deserve it! even if it's not a ~problematic~ cruelty! even if you agree with all of that blog's opinions!

it's one thing if someone snaps back when provoked or posts the occasional "get a load of this guy". nobody needs to play up respectability for people who haven't given them respect in return. but if someone's online identity centers around being needlessly mean for laughs + they're constantly seeking out socially acceptable, easy targets for petty cruelty, that's a red flag. there's a huge difference between not taking shit/cracking a joke + mocking others as your several-hours-a-day hobby.

especially if, when they are inevitably in the wrong + mocking someone mercilessly to their 50k followers over something petty goes south (shocking!), they become extremely defensive or block everyone or play the victim or dismiss it as "well, how was i supposed to know they were autistic? i'm autistic + i don't meow in public" or whatever.

this isn't a "well i knew all along" post bcuz nobody should be shamed for being in the dark about something like this but many of the popular bloggers who have later been exposed for serious harassment or abuse should not have shocked us. if someone's blog is 90% shit like "you should light yourself on fire because you watch x anime" or "look at this so-called lesbian bitch + her ugly fucking boyfriend at a kink convention- it's giving drowned rats", should it really shock you that they are also being cruel or abusive in less internet-acceptable ways? if they've already shown you that they get a such a thrill out of being vicious that they do it daily + are regularly rewarded with thousands of followers?

#it's so bad on other social media platforms too#like the number of tiktokkers whose fame is just being MEAN but in a funny way#towards ppl who have done nothing to deserve it but also are not like. oppressed groups#half the time it's ppl who i also personally dislike or dont relate to but don't deserve like. repeated violent harassment#like sure i also dislike marvel movies but it's far more embarassing to run a blog dedicated to mocking + suicide baiting random marvel fan

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

I have a short fuse when it comes to things like this. They’ll be too loud or something and I’d snap and tell them to stop…

Neurodivergent Girl

#autism#actually autistic#sensory overload#it makes some angry#I find this relatable#I’m sure some of you do too#I hate snapping at others#but i can’t help it#Neurodivergent Girl (Facebook)#feel free to share/reblog

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Gregory canonically has the best dad in FNAF

#myart#chloesimagination#comic#fnaf#glamrock freddy#fnaf gregory#micheal afton#fnaf vanessa#fnaf vanny#security breach#fnaf fanart#five nights at freddy's#sorry to Vanessa and Michael but Gregory simply can’t relate#it’s actually funny that glamrock Freddy might be the best dad#seeing he’s an animatronic and bears out most human fathers 😭#who knew just being a silly guy can make you such a good father it was that easy#least Nessa and Michael can relate to each other on this#they got each other 🙏🏾

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

Why are trans men constantly gaslit about our lived experiences?

We try to talk about how we’re denied reproductive care and are treated as others in gynecological spaces. We should not be outliers or things of ridicule or disgust in these spaces. These are spaces where we should be welcomed like any cis woman would be. We are treated like this even when we need gynecological care because we are trans men.

We try to talk about how TERFs oversexualize us while infantalizing and talking down to us. They act like they have ownership of our bodies, and like we need them to guide us to “accepting” ourselves as women. They do this because we are trans men. People have started calling them TWERFs instead, because they like to believe that we are included on behalf of TERFs wanting to change our minds and bodies, and claiming that they will have open arms for us when we’re “done with our phase.” (Being sexualized is especially true of straight trans men. Gay trans men will be constantly subjected to fatphobic stereotypes, and plenty of things that are just “LIBERAL SJW,” misogynistic stereotypes turned around and used against someone who it’s slightly more acceptable to hurt. This is okay to so many people because we are trans men.)

When we point out any ways that we face oppression, we have 500 people screaming that another group has it worse. Depending on the group, they claim that we’re either privileged men or privileged little girls complaining about nothing.

There is no way for us to win in society’s eyes. We are constantly silenced and spoken over, even by some of our siblings. Trans men deserve to be respected. Trans men deserve to be understood. Trans men deserve to be accepted.

Trans men deserve to be believed.

#trans#transgender#transandrophobia#transmisandry#trans man#trans men#plenty of this is also relatable to other transmascs#I just say trans men because I am one and don’t want to speak for transmasc nonbinary people whose experiences I am not as familiar with#feel free to add on if you’re transmasc or posting in support of us

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

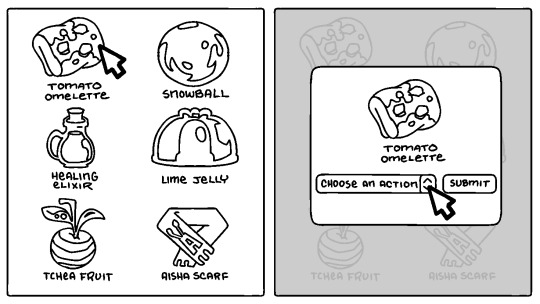

the continued adventures of an internet user who was frozen in 2004 and defrosted in 2021: some things are just the way you left them

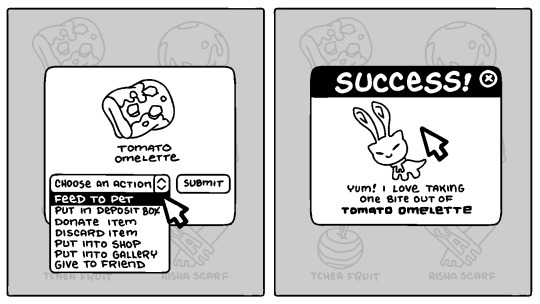

previous 2004 internet user comics are here: one, two, three, four, five; or just in my 2004 tag

#2004#art#comic#comics#internet#nostalgia#neopets#aisha#february 2024 art#2024 art#02132024#did i... forget to upload this one on tumblr in february lol#too distracted by mewtwo's birthday i guess#i have been playing neopets since elementary school#we're talking barely sentient#and i still play every day#it's not really my intention to make a low effort Relatable Comic here#but to capture a specific feeling i have when i feed my neopets#pet sims are unlike anything else to me#they just have this feeling about them that is more intimate than other games even when it's basic text and images#i guess that's why my comic is like#Pet Sim But Sad#lmao

5K notes

·

View notes